Online Extras

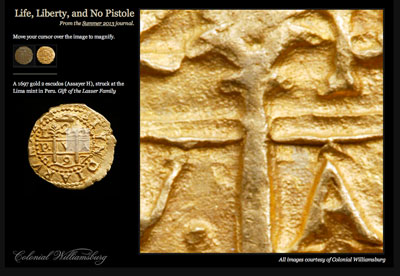

Zoom in on Pistole Coins

David Doody

In 1752, the Reverend Mr. William Stith presented a tavern toast to life and liberty, and a small gold coin called a pistole, to protest against an arbitrary government fee. Todd Norris, left, as Stith, with Jason Belew, Chris Allen, Bryan Austin, and Jay Knowlton recreate the scene.

Dave Doody

Before becoming president of the College of William and Mary, Stith served seven years as master of its Wren Building grammar school. Here he and students—from left, Fielding Kiser, Alan Burkett, Christopher Hochella, and Colin McKenzie—chat after class.

Dave Doody

Stith checks sheets printed by William Parker of his 1747 History of the First Discovery and Settlement of Virginia. The book was the first of its kind published primarily for an American audience. Journeyman printer Peter Stinely as Parker, with David Wilson.

Barbara Lombardi

Consulting earlier accounts for his history when he could, and drawing on copies of original Virginia documents in Williamsburg, Stith’s money-losing book was for centuries a standard one-volume reference for Virginia’s earliest years.

Life, Liberty, and No Pistole

by Susan Berg

Twenty-three years before Virginia patriot Patrick Henry said, “Give me liberty or give me death,” the Reverend Mr. William Stith of Williamsburg raised a glass and toasted “Life and liberty, and no pistole.” That sparked a protest against Lieutenant-Governor Robert Dinwiddie that spread throughout the colony and across the Atlantic to the upper levels of English government. For his 1775 ultimatum on the eve of the Revolution, Henry is well known as someone who helped to persuade the colonists to break away from England. Stith is unfamiliar. Who was he and what did he do?

Few colonial Virginians who rose to prominence left as complicated a legacy as Stith. By the time of his death, at the relatively early age of forty-eight, he had ministered to an Anglican parish, written a scholarly history of the colony, served as president of the College of William and Mary and as chaplain of the House of Burgesses, incurred the enmity of Virginia’s governor, and begun a protest that was a precursor to conflicts that led to the American Revolution. People who have heard of Stith may know him as a pedantic historian. How did this reputation obscure what was perhaps his greater contribution as one of the pre-Revolutionary Virginians who paved the way toward independence?

Born in Charles City County, Virginia in 1707, Stith was the eldest son of John and Mary Randolph Stith. At seventeen, he entered Queens College, Oxford, from which he graduated seven years later with BA and MA degrees. There he was ordained as a clergyman in the Church of England. Little is known about Stith’s education in Oxford. The only description appears in a letter he wrote to Thomas Sherlock, the bishop of London, in 1753, saying: “What I shall ever esteem one of the greatest Felicities of my Life, the Opportunity of a liberal Education in England, among a People justly famous for their good Sense & Principles of Liberty.”

Returning to Virginia, Stith was elected master of William and Mary’s grammar school, and for seven years oversaw the education and physical and moral discipline of its students. During that period, he frequently visited his favorite uncle, Sir John Randolph, who lived at Tazewell Hall—a mansion that stood near today’s Williamsburg Lodge, but was moved to Newport News in the 1950s—and made use of his extensive library, invaluable to Stith when, years later, he wrote his history.

In 1737, he secured appointment as minister of rural Henrico Parish near Richmond, a position with fewer obligations than a grammar school master’s. He married his first cousin, Judith Randolph, daughter of Thomas Randolph of Tuckahoe plantation, with whom he fathered three daughters. Preparing sermons and performing the occasional marriage and funeral services gave him time to pursue his major interest: writing a scholarly history of Virginia.

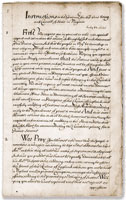

Publishing The History of the First Discovery and Settlement of Virginia in 1747, Stith was the first person to write primarily for Virginians and not for an English audience. He avoided the practices of scholars who, without questioning their accuracy, published chronicles of voyages and travel accounts from earlier writers, or who wrote history as a revelation of God’s will in human affairs. Stith thought it essential to examine and evaluate the original records from the early settlement period, sources he thought contained the historical truth and that in the future might be lost. He believed that previous histories of the colony, with the partial exception of Captain John Smith’s The Generall Historie of Virginia, New-England, and the Summer Isles, published in 1624, were incomplete and unsatisfactory. Stith’s preface said:

That had any thing of Consequence been done in our History, I could most willingly saved myself the Trouble, of conning over our old musty Records, and of studying, connecting, and reconciling the jarring and disjointed Writings and Relations of different Men and different Parties.

In this sentence, he explains the reason for this undertaking, and describes the challenging tasks that historians encounter in their research.

In addition to Smith, Stith consulted other books, among them Theodor de Bry’s 1590 edition of Thomas Hariot’s A Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia, Robert Beverley’s History and Present State of Virginia from 1705, and Hugh Jones’s 1724 Present State of Virginia. He reviewed the records of the Virginia Company of London, which, through a succession of royal charters, governed the colony from its founding in 1606 to the company’s dissolution in 1624, and he visited clerks’ offices in Williamsburg looking for early government records.

In an age when scholars had to travel extensively to review original sources and did not have the use of photographically or digitally reproduced documents, he examined 50 percent of the existing material from that period. English libraries and institutions had the remaining books and documents. His inclusion of the transcripts of the company charters of 1606, 1609, and 1612 in an appendix to his book shows how much he valued early records.

Stith’s work earned him a reputation as a serious historian. His book was a standard source for early Virginia history for more than one hundred and fifty years, and nineteenth-century scholars of American history adopted his methods. During the past eighty years, however, he has lost credibility. Relying solely upon the company’s records to determine why the crown recalled its charter and took over the colony, he was blind to the bias later historians found in those documents.

Stith allowed his political prejudices to influence his writing. He drew selectively from his sources, omitting criticisms of individuals he admired and neglecting to include noteworthy deeds of those he scorned. He portrayed James I as a contemptible monarch who arbitrarily dissolved the company, a legitimate governing enterprise. Exempting living monarchs from scrutiny, he believed it was a historian’s duty to criticize the absolute power of deceased rulers and to expose their faults to ridicule. He venerated the principle that a representative government was superior to monarchical rule. Imposing his perspective, Stith was demonstrating “presentism,” a twentieth-century term that describes how historians, often unconsciously, incorporate their own values in their interpretation of the past rather than acknowledge the prevailing views of the period.

Stith’s History was the most significant work to come from the Williamsburg press. Since 1730, when printer William Parks set up shop, he had distinguished himself with the titles he published, first, issuing the laws and journals of the General Assembly for the colonial government and, later, producing newspapers, almanacs, pamphlets, and books. In 1742, Parks printed the first cookbook in America, The Compleat Housewife by E. Smith, and five years later, followed it with Stith’s work, for which he used paper from his local paper mill.

In his newspaper, the Virginia Gazette, Parks advertised for subscribers to the book in advance of publication, and the volume sold relatively well. Most large planters and such minor ones as John Mercer, owned a copy; however, Stith, who invested some of his funds in the publication, said he lost £50 on the venture. His book appealed to the English publisher Samuel Birt, who issued a London edition in 1753. The bibliographer Joseph Sabin published a facsimile edition in 1865. Today, more than fifty copies of the original book survive, the greatest number of any work printed in eighteenth-century Williamsburg.

Stith’s History provides a window into the values and attitudes of Virginians in the mid-eighteenth century. It may be better known for Thomas Jefferson’s critique. In 1784, he wrote of Stith and his book: “He was a man of classical learning and very exact, but of no taste in style. He is inelegant, therefore, and his details often too minute to be tolerable, even to a native of the country.”

Stith had intended his book, which concluded in the year 1624, to be the first part of a multivolume Virginia history that continued to his day. Whether because of a lack of interest or funding, difficulty locating original sources, or other reasons, he did not write any subsequent installment. Five years later, in 1752, he was at the center of a political issue that challenged royal authority: the Pistole Fee Controversy.

Newly appointed Lieutenant-Governor Robert Dinwiddie, hoping to increase revenue, tried to impose a fee of one pistole, the equivalent of sixteen shillings and eight pence, to affix a seal on land patents granted by the crown. He was following the example of the other royal colonies, but in Virginia the House of Burgesses as far back as the 1680s had assigned and regulated fees by law. Dinwiddie sought the approval of the London Board of Trade and the appointees to the Virginia Council to impose the fee. He did not ask the House of Burgesses, an elected body that had exercised that right, and he was confronted with widespread resistance.

Stith became the unlikely leader of the opposition, igniting protest with a defiant toast. His words became a rallying cry against the fee. Stith and a group of his countrymen—headed by his first cousins Peyton Randolph and Richard Bland—were not opposed to the fee per se, or to increasing royal revenue. Their protest focused on Dinwiddie’s right to impose the fee, which they considered illegal. Bland echoed Stith’s words, writing: “Liberty and property are like those precious vessels whose soundness is destroyed by the least flaw.” Years later, a Virginia clergyman wrote in a letter from the western frontier: “I believe it is the general opinion here that liberty and property, once lost, a people have nothing left worth contending for.”

Refusing to accept Dinwiddie’s right to levy the fee, Stith was adhering to the Whiggish principles that he likely had adopted at Oxford and that had strongly influenced his writing as a historian. British Whiggism, which arose during the seventeenth century, was based on the principles of a constitutional monarchy and opposed the absolute rule of kings. Englishman John Locke was one of its principal proponents. In 1690, discussing natural law, Locke wrote that men “being all equal and independent, no one ought to harm another in his life, health, liberty.” The Founding Fathers admired his individual rights and limited government philosophy.

The disagreement was unresolved eighteen months later, in November 1753, when the House of Burgesses, responding to constituent petitions, wrote to the governor asking upon what authority he was imposing the fee. Dinwiddie said he had acted with the approval of the Virginia Council. That did not satisfy the House, which said: “the demand of a pistole . . . being not warranted by any known or established law, is . . . an infringement of the rights of the people.” When Dinwiddie refused to back down, the burgesses appointed Peyton Randolph to go England and present their case before the Privy Council.

News of the Privy Council’s decision reached Virginia in October 1754. The governor was allowed to levy the fee but not for lands of less than one hundred acres, for lands beyond the mountains, or for lands where applications for patents had been initiated before April 1752, when the fee was proposed. It was a partial victory for the governor, but it set an example of rebellion by the burgesses.

Stith paid a price for challenging Dinwiddie. Soon after the controversy began, William Dawson, president of the College of William and Mary, died, and Stith was elected president. The holder of that office also traditionally was appointed commissary to the Bishop of London, oversaw Virginia’s Anglican parishes, and took a seat on the council.

Dinwiddie wrote to the Bishop of London to promote Thomas Dawson, brother of the late president, for commissary and to damage Stith’s chances for the post. In a letter to an English friend, Dinwiddie identified Stith as the cause of his troubles in Virginia and said the colonists had been “very easy and well satisfied till an Evil Spirit entered into a High Priest, who was supported by the Family of Randolphs.” Stith never got the appointment or a council seat. He died in 1755, after serving as college president for three years.

A decade later, the colonies began to unite against the Stamp Act and what they believed were unjust and illegal laws passed by Parliament. In Virginia, Stith’s cousins Randolph and Bland joined another Randolph family member, Thomas Jefferson, and others to oppose these new policies. Echoing Locke and Stith, this opposition appeared in 1776 as a phrase in a new document, “Life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.”

Susan Berg, former director of Colonial Williamsburg’s John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, contributed to the winter 2012 journal “Looking for the Real Captain Cook.” She thanks Thad Tate, Martha McCartney, and the late Darrett B. Rutman for their assistance with this article.