Online Extras

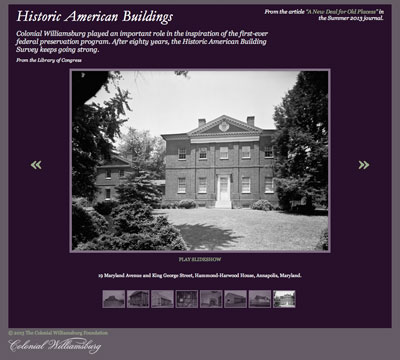

Historic American Buildings Slideshow

Colonial Williamsburg

The Grissell-Hay outbuildings, before their restoration based on the detailed surveys pioneered by HABS and Colonial Williamsburg.

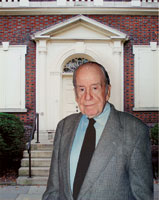

Dave Doody

Colonial Williamsburg curator of architecture Willie Graham, next to the restored Grissell-Hay buildings, began his career with HABS.

Colonial Williamsburg

Telephone and power lines were laid underground on Duke of Gloucester Street to remove signs of twentieth-century life when the colonial capital was restored.

Colonial Williamsburg

During FDR’s visit to Williamsburg in 1934, he met W. A. R. Goodwin. Pastor of Bruton Parish Church and father of the Restoration; Eleanor Roosevelt and an aide are on the right.

Colonial Williamsburg

The Palmer House before restoration, where Peterson lived after moving to Williamsburg to observe the way architects were reconstructing the eighteenth-century town.

Colonial Williamsburg

William Perry of Perry, Shaw & Hepburn, the Restoration’s architectural firm from Boston.

Colonial Williamsburg

Architects and draughtsmen for Colonial Williamsburg, who, like those from HABS, brought accuracy and rigor to preserving historic structures.

Library of Congress

Peterson restored Moore House in Yorktown, where surrender documents were prepared after Washington’s victory. His study for the building became a model for historic preservationists.

Library of Congress

The Moore House in decline, photographed during the Civil War. It was preserved, but by 1966 nearly half the historic buildings that HABS architects had surveyed were gone.

Library of Congress

HABS photo of the Long Lane Farmstead in St. Mary’s County, Maryland. The house, built around 1674, later passed into the hands of the Carroll family. It was demolished in the 1990s.

Library of Congress

E. H. Pickering took this photo of the Charles Carroll of Annapolis House in Maryland for HABS in 1936. Dating to the 1720s, it was restored and is open to the public for tours.

A New Deal for Old Places

by W. Barksdale Maynard

The New Deal spawned an alphabet soup of programs to benefit the poor and jumpstart an economy mired in Depression. Eighty years later, a handful survives, including the TVA, the Tennessee Valley Authority, and the FDIC, the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. Then there is HABS: the Historic American Buildings Survey.

Established in 1933 as the first-ever federal preservation program, HABS was intended to last a few months. It is still going strong, having investigated and recorded 41,000 historic buildings and sites, and amassed a record of American architecture.

HABS can be traced to Colonial Williamsburg. It was the brainchild of Charles E. Peterson, a landscape architect for the National Park Service. He spent 1930–33 in Tidewater—establishing Colonial National Historical Park and laying out Colonial Parkway. As he told me not long before his death in 2004, he lived on Duke of Gloucester Street in Williamsburg, adjacent to the Capitol site, and watched the Restoration with deep interest.

Transferred in 1933 to the Park Service office in Washington, DC, Peterson heard that the Civil Works Administration, charged with creating jobs for the unemployed, was asking for ideas to implement immediately. Pencil in hand, Peterson sat down on a Sunday afternoon in November and wrote the proposal for HABS.

He outlined a $450,000, four-months’ program to give work to 1,000 architects, a profession hit hard by the downturn. Because little equipment was needed, they could start right away. Their mission: to record with cameras and drafting supplies “the important antique buildings of the United States.”

The Williamsburg Restoration was prominent in Peterson’s mind. Upon moving to Virginia, he had chosen to live in Williamsburg, he said, “because that was where architecture was going on.” Those were heady times. “As he hobnobbed with the architects at Colonial Williamsburg,” says James Massey, head of HABS from 1966 to 1972, “he became part of a great foment around Williamsburg and the idea of the colonial.”

The day he arrived, Peterson called upon the Reverend Dr. William Archer Rutherfoord Goodwin— sometimes irreverently called Willie. Goodwin had proposed the Restoration to John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1926, after showing the philanthropist the city and its Wythe House. From out of his cluttered library Peterson handed me a copy of Bruton Parish Church Restored, inscribed with Goodwin’s florid signature September 27, 1930. Goodwin and architect J. Stewart Barney were responsible for Bruton’s 1907 restoration. Goodwin left its pulpit for a New York parish, but in 1926 became its rector again.

Goodwin found Peterson a place to live, the Palmer House by the Capitol, then occupied by the Jim Christian family. In a wooden barn out back, Peterson parked his Model A Ford with rumble seat.

Christian knew where to get white corn whiskey for a dollar and a quarter a gallon, Peterson said: “All of Tidewater society floated on a river of corn whiskey.” The local drafting room of Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn, architects of the Restoration, saw convivial after-hours poker games and drinking white corn.

“Not one house in fifty had a coat of paint on it,” Peterson said. “The only place they had to hear an orchestra was at the insane asylum.” The reference was to Eastern State, the oldest mental hospital in the United States. At parties, Peterson danced the Norfolk Shag and ordered a corsage for his date from the town undertaker. Goodwin enjoyed socializing, too, and in his genial way “liked to pinch the ladies.”

Peterson got to know the architects of the Restoration, admiring their attention to historical accuracy. In just the way that HABS would later, they fanned into the countryside, recording colonial landmarks with measuring tapes and cameras, determined to understand the builder’s art from a bygone age.

“They were going out and ‘grabbing’ details that were of interest to the Restoration, like a box cornice or end-boards or stair balusters,” says Willie Graham, curator of architecture at Colonial Williamsburg today. “They wanted to understand the regional vernacular—nobody had done serious research in the South before.” HABS would expand this strenuous approach nationwide.

Trained as an architect—University of Minnesota, Class of ’28—Peterson was fascinated by the Williamsburg architects and how their “drafting rooms were full of adventure and excitement and every junior architect was working on a book of his own.” He was impressed by their command of the details of colonial architecture and the “brilliant success” they achieved as designers.

Peterson, too, was developing a concern for excellence. In later years, “He was constantly harping on professionalization,” says preservation expert William Murtagh, who met him in the late 1940s. “You had to be a very good draughtsman.”

Peterson’s work at Yorktown plunged him into the intricacies of historic architecture. By establishing a presence in the eastern United States, the National Park Service had diversified its mission beyond mountains and forests: Colonial National Historical Park, founded 1930, had old buildings that needed preservation, most prominently the Moore House, where surrender documents were drafted after George Washington’s victory at the Siege of Yorktown.

Approaching his task with scientific rigor, Peterson restored the Moore House as accurately as possible and wrote the first-ever historic structures report explaining what he had done, and why. Historic preservation experts of today consider Peterson’s report a milestone in professionalizing the trade. “It’s the first of what we now take for granted,” says Roger Moss, a leading preservationist in Philadelphia. “Preservation had not been systematically approached before.”

Living in Tidewater, Peterson watched firsthand the encroachment of modern life on ancient landscapes, the destruction of old buildings. He designed Colonial Parkway to blot out all view of what one contemporary called “a succession of hotdog stands and tire signs.” When he sat down to write the HABS proposal, he stressed how our built heritage “diminishes daily at an alarming rate.” The program offered the chance to keep history alive, at least in file cabinets bulging with documentation.

“From the cultural standpoint an enormous contribution to the history and aesthetics of American life could be made,” Peterson wrote of his HABS idea. But Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes had final say. To persuade him, Peterson enlisted the architects and advisors of Colonial Williamsburg.

Seventeen, including Goodwin and Perry, wired a telegram to Washington on November 16, 1933, to “express approval of the project. The plan as detailed impresses us as an admirable method of accomplishing a work of historic importance.”

Impressed, four days later Ickes approved HABS. But he disliked Peterson personally and, the preservationist would later say, refused to see him put in charge. Instead, Peterson’s boss Thomas C. Vint and architect John O’Neill oversaw the fledgling program.

It wasn’t just Ickes who found Peterson difficult. “He wouldn’t take no for an answer,” Murtagh says. “And if he got his teeth in the seat of your pants, he would never let go.” Peterson’s devotion to worthy causes won him many friends and enemies and, eventually, the title “father of historic preservation”—a sobriquet he didn’t mind at all.

Given the green light, HABS fieldwork was well under way by January 1934, involving 772 newly employed architects. Its temporary mandate was extended, and during the next eight years, 7,000 historic structures were visited and written up on index cards. Half were photographed; one-third were drawn and measured. Written reports were prepared as well, recalling Peterson’s innovative work at the Moore House.

HABS was and remains an unusual public-private partnership: operated by the National Park Service, advised by the American Institute of Architects, donating materials to the Library of Congress. The latter two institutions had collaborated on “Pictorial Archives of Early American Architecture” as early as 1930, proof that the HABS idea was not entirely original. “To credit only Peterson is to deny the contributions of many others,” says current HABS chief Catherine Lavoie. She seeks to distinguish between fact and myth concerning this larger-than-life man.

Links between HABS and Colonial Williamsburg were tight. Perry served on a seven-member National Advisory Committee for HABS. Assistant HABS director Thomas T. Waterman had worked as an architect for the Restoration from 1928 to 1933 and used HABS materials in his book, The Mansions of Virginia. Working closely with Waterman was Frederick Nichols, smitten with Jefferson’s legacy while surveying in Virginia. Years later, as a University of Virginia professor, Nichols restored its Jefferson-designed Rotunda.

HABS stressed authenticity, not speculation. Its guiding documents of December 1933 said old buildings were to be shown in their “exact present condition,” no matter how degraded, and that architectural drawings must not include “conjectural restorations.” Data sheets, too, must stick to the facts: “Long accounts of genealogical matter and sentimental mythology have no place in the program.”

A sign of Williamsburg in HABS was its catholicity of vision, which appreciated not just landmarks but “structures of all types . . . barns, bridges, mills, toll houses, jails, and in short buildings of every description are to be included so that a complete picture of the culture of the time as reflected in the buildings of the period may be put on record.”

This kind of broadly cultural view had been pioneered by the Restoration, which faced the task of rebuilding a colonial town down to privies and a jail. Peterson said he had been impressed by the diverse architectural drawings of the Williamsburg restorers, which ranged “all the way from wooden smokehouses in backyards to the great, reconstructed Governor’s Palace.”

Along with the New Deal, HABS surveys sputtered out with World War Two. Peterson joined the Navy. But the program was revived in the late 1950s at a time that Peterson, back working for the Park Service in Philadelphia, was pushing harder than ever for historic preservation in the face of urban renewal. He cheered HABS’s return.

Employed by the Park Service, Jack Boucher was HABS’s photographer for half a century, starting in 1958 with a venerable wood-framed Kodak Century view camera. “Peterson was my first boss,” Boucher says. “He was always 100 percent behind HABS and considered it his baby. Williamsburg is where he got interested in preservation.”

Nor was Peterson quite finished there. One of his later projects—he lived to age ninety-seven—was to research the career of eighteenth-century Philadelphia architect Robert Smith. This brought him to town once more, from 1981 to 1985, to advise on the rebuilding of the Public Hospital, designed by Smith and the original Eastern State.

To Peterson’s great pride, the revitalized HABS spawned the Historic American Engineering Record in 1969 and the Historic American Landscapes Survey in 2001. Files from the programs are available to everybody online, a collection of nearly 400,000 photographs, architectural drawings, and written accounts.

Survivor of thirteen presidential administrations and the swings of innumerable budget axes, HABS provides us with a record of old American buildings. For many of them, it is our only record: Nearly half the structures HABS recorded in its early years were gone by 1966.

Traditionally, HABS focused on places “in imminent danger of destruction”—Mount Vernon, for example, was never drawn because it was safely preserved as a shrine. But recently HABS has recorded such national landmarks as the Jefferson and Lincoln Memorials in Washington. After a 2011 earthquake damaged the Washington Monument, HABS photographs from 1993 and 1994 provided useful images of the obelisk before the cracking.

Amid fiscal stringencies, much of HABS’s work has narrowed to Park Service sites. As technology progresses, meticulous hand drawing with ink pens has given way to computer-aided drafting. Laser scanning allows certain buildings to be recorded quickly, including structures too huge to measure with a tape.

Yet HABS remains traditional, insisting upon first-rate documentation that will endure in the archives. Under Lavoie, its chief since 2007, HABS has resisted a growing clamor for digital photography. That new technology falls short in terms of “quality, reliability, image integrity, and endurance,” she says. Long-term storage of digital files presents problems of cost, as do digital cameras, which quickly become obsolete. HABS gets good use out of its Linhof film camera bought for Boucher about 1964.

Something of a legend for his HABS career and the tens of thousands of photos he took, Boucher says, “Otherwise it’s totally impossible for HABS to maintain the integrity of an image, because with digital they can be altered by the photographer, and it’s very difficult to tell.”

Every state has benefited from HABS. A landmark church that burned to the ground in Alaska was promptly rebuilt using HABS drawings. By the time of the Bicentennial, HABS had visited 3,800 Virginia buildings, and more have been recorded since. One of the program’s achievements was the 1989–92 campaign to measure and draw Monticello down to its individual floorboards.

Williamsburg was recorded by HABS in the Jimmy Carter years. A college-age Graham drew the Grissell Hay outbuildings for the program in 1979, little imagining he would make a career as a foundation employee. “HABS prepared me well for what I later did working for Williamsburg,” he says. “It really taught me how to look at historic buildings.”

Eighty years after Peterson proposed a four-month program, HABS endures, helping in drawings and on film to preserve America’s most historic and vulnerable buildings.

W. Barksdale Maynard contributed to the summer 2012 journal a story on the preservation of Revolutionary War battlefields. He is author of five books on American history, including Woodrow Wilson: Princeton to the Presidency.