Digital History Center

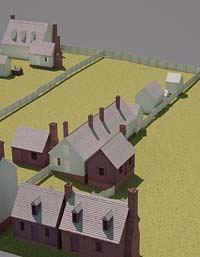

A drawing of the armory, center, with the tin shop to its right and kitchen to the left, limns the heart of the Anderson complex.

The author, right, reviews progress on excavation at the tin shop site, to be part of the reconstructed Anderson Armoury, with staff archaeologist Mark Kostro.

Jeffery E. Klee

Master carpenter Garland Wood, right, works with Jack Underhill on framing one of the Anderson Armoury buildings.

Complex Reconstruction: The James Anderson Armoury

by Edward A. Chappell

Restoration and reconstruction best serve education when they encompass sites as opposed to single buildings, because the research must be more widely conceived and because a unified landscape of buildings offers a richer and more compelling portrait of life in the past. Just as Colonial Williamsburg's George Wythe House is more evocative because of its Palace Green location, the Historic Area's Peyton Randolph House became more comprehensible with the reconstruction of its lost outbuildings. The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation is positioned to do such work because of its commitment to diverse research on the material life of eighteenth-century Anglo America.

Most restoration or reconstruction is expensive, so it is only done when substantial funds are available. But the ability to do such work well depends on a dedication to scholarship. Since 1927, foundation scholars have captured rich information about specific buildings and landscapes, and about the nature of housing and work environments in the Revolutionary age. The work on Historic Area sites is multigenerational.

The James Anderson site on Duke of Gloucester Street is an example. The Frenchman's Map, a 1782 plan of the city that guides Williamsburg's restoration, roughly shows the size and position of five buildings within the property that blacksmith and public armorer James Anderson acquired in 1770, and the map was scrutinized before the first excavation was done there in 1932. That digging found fragmentary brick remains of the house, often used as a tavern before Anderson's ownership, as well as the principal blacksmith shop and its forges, two detached kitchens, a well, three other outbuildings, and two brick-vaulted drains. The house was reconstructed in 1940, accompanied by the eastern kitchen, a part of the shop, and a privy.

The site was one of several targeted for new study and re-creation in the mid-1970s, intended to broaden the foundation's presentation of Williamsburg life in the 1760s and 1770s, supported by the Rockefeller Brothers Fund. Ivor Noël Hume directed and Robert Foss managed an archaeological reinvestigation of the site. The earlier excavators, led by James Knight, had dug parallel trenches before striking masonry, which he uncovered and measured. Noël Hume and Foss took a more developed approach, studying soil stains and the position of artifacts to recognize non-masonry features and to interpret the site's evolution. They discovered that parts of the main work structure and its forges had been robbed of their brick after the Revolution and identified the west kitchen—not the reconstructed east one—as having been built before circa 1760 and used to serve the adjoining tavern until the 1770s.

The size and location of the ironworkers' forges were relatively clear, but the sequence of outer foundations was difficult to read because the remains were fragmentary. Foss hypothesized that the main forge building evolved in phases as James Anderson expanded his blacksmith operation. Based on these findings, my foundation colleagues and I developed a reconstruction of the blacksmith shop in the early 1980s that expanded the spectrum of eighteenth-century building practice guests could visit. The reconstructed workshop exemplified the rougher, cheaper, less-permanent structures that shared the eighteenth-century Chesapeake landscape with such refined and durable buildings as the gentry and artisans' houses for which Colonial Williamsburg is known.

We repositioned the reconstructed privy and second kitchen and conducted six excavations between 1983 and 2000 as steps toward re-creating the Anderson complex. This work explored a southern ancillary building and the work yard, and it uncovered ghostly remains of a post-1782 forge to the east. The Anderson shop became a popular exhibition under the direction of master blacksmiths Peter Ross and Kenneth Schwarz. Their team of smiths produced almost all the specialized hardware used at Colonial Williamsburg and other museums, all in front of an audience of 300,000 visitors a year.

Time encouraged the hopes of the architectural historians and blacksmiths to complete the site's restoration. The additional excavations, for example, found evidence for tinsmithing that matched Anderson's ledger entries for purchasing tin and paying tinsmith Nathaniel Nuthall. The excavators learned that much of the ironworking and earlier refuse one could expect to find in the work yard had been removed and perhaps redeposited nearby.

Schwarz studied Anderson's account books, finding an unstudied one in the Daughters of the American Revolution archive in Washington. Close reading of the volumes showed the shop was built in wartime, when the need to maintain arms for the Continental Army and Virginia militia required expanding the operation, at state expense. Schwarz says Anderson's prewar blacksmith work was confined to the adjoining Barraud property, where Anderson resided, leading us to reevaluate the periods archaeologically assigned to the foundations in the 1970s.

Williamsburg mason Humphrey Harwood was paid for constructing those foundations August 13, 1778, when he billed the commonwealth for "underpinning the armourer's shop" with 6,950 bricks. Delivery of 13,000 nails to carpenter Phillip Moody that October—also for the armory—further indicates that the large structure was erected in a single campaign. Ledger entries for hinges in the public store records allowed us to calculate how many doors and shutters enclosed the building.

The interpretation of the written records began to focus on Anderson's role as public armorer at this site from 1778 until his operation moved with the government to Richmond in 1780. The re-created complex could, then, serve as more than a portrait of the largest trade work site in 1770s Williamsburg. It could portray the degree to which the town was pressed into service to support the war. Given its potential for strengthening the foundation's Revolutionary City educational program, a proposal was developed for Colonial Williamsburg donor and board member Forrest E. Mars Jr., who agreed to fund the project. This effort would include further archaeological investigation, design, and construction, overseen by James Horn, Colonial Williamsburg's vice president of research and historical interpretation and the Abby and George O'Neill Director of the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library.

We began excavations in 2010 by more closely studying remains of the kitchen and structures extending south of the armory toward Francis Street, and by exploring the perimeter. Work on the kitchen shows how new technologies can be turned on previously studied evidence to provide additional information. Noël Hume and Foss had found a pattern of plaster refuse seemingly tossed from the front door of the kitchen into the yard behind the house, as well as evidence for a clay floor. This helped define the character of the cookhouse as sufficiently well built to be partially plastered but sufficiently inferior to have a low earth floor. But precisely what kind of plaster and earth? Earlier excavators purposely had left areas of the plaster scatter and the floor in place, so we could extract and microscopically analyze how lime, sand, and brick dust were mixed with clay for the floor, and how brown plaster was applied to oak lath and whitewashed before its removal about 1800.

We have long studied buildings that housed cooking and enslaved workers in the early Chesapeake region, and the new reconstruction incorporates findings drawn from these and other structures. This includes such choices made to reduce construction costs as riving the siding in four-foot lengths of clapboard lapped and nailed to studs on two-foot centers rather than the then more costly sawn and beaded weatherboards. Often ephemeral, their survival is rare.

Historic Trades carpenters led by Garland Wood are reconstructing the armory buildings present in 1778, employing eighteenth-century techniques, much as they did earlier at the Peyton Randolph House. As at the more-recent coffeehouse reconstruction, they are working with Historic Trades brickmakers, who are hand-molding the bricks and burning them in clamps modeled on the archaeological remains of temporary brick kilns in the region. They are laying the masonry under the tutelage of Raymond Cannetti. Viewers watch the work on the foundation website thanks to two full-time webcams, which capture the drama of orchestrated wall raisings and the pace of laying bricks in shell mortar, one at a time.

Architectural historians Willie Graham, Jeff Klee, and I are designing the buildings in collaboration with Wood and Schwarz. Wood, for example, has argued for wartime use of lumber sawn in waterpowered mills and used elsewhere in Virginia but seldom seen in pre-Revolutionary buildings in and near the capital. Schwarz balances our experience in studying regional work buildings with his in making and repairing ironwork in the manner used by Anderson's workers.

Sustained excavation in Williamsburg allows us to recognize patterns of how the community organized its functions spatially, such as placing freestanding kitchens behind houses and taverns and raising other buildings along secondary edges of property controlled by constructing fences. Williamsburg was laid out in a formal manner in 1699, and lots were sold, divided, and combined in rectangular arrangements for more than two centuries. But the urban plan was laid over an uneven landscape, and residents filled in ravines, redirected rainwater, and disposed of refuse in ways that made the undulating topography better conform to a Cartesian civic grid.

Excavation at the perimeter of the Anderson yard illustrates this in ways that reveal how warfare disrupted old boundaries. Fences enclosing the Anderson lot were built and rebuilt throughout the eighteenth century, leaving posthole stains, often cutting into one another. For about two decades before the Revolution, the armory site was a busy tavern. Its kitchen workers and others threw garbage over the property fence to the west, gradually filling a ravine traversed by a city-built, brick-vaulted drain that still passes under Duke of Gloucester Street and empties beside the Printing Office. Faunal archaeologists Joanne Bowen and Steve Atkins's initial study of the remains reveals that the taverns served dishes ranging from sturgeon to goose. This was gentry fare.

A large, roughly built, all-wood stable seems to have stood on the east side of the ravine, possibly one mentioned in a 1745 advertisement for the western property, and resembling an earlier stable on the James Wray's construction yard off Nicolson Street. By about 1770, the structure was demolished, and replaced with a better-built workshop hugging the edge of the trash-strewn ravine.

Anderson recast his lot and part of the adjoining property to serve the war effort as the government armory. Harwood and Moody built an armory containing four forges with bellows squeezed between the kitchen and the western shop. Anderson pulled up a fence that had separated the old domestic work yard from the tavern's rear gardens and paddocks, and built fences to control public access from Duke of Gloucester Street while securing the newly enlarged yard for trade work.

The latest archaeological evidence suggests that it was then, just before heavy work began at the armory, that additional brick-vaulted drains were constructed to remove rainwater from the yard and wastewater from the kitchen, now serving metalworkers instead of tavern guests. The brick drain descended into the ravine and connected to the major line passing under the street. Someone other than Harwood built masonry rapidly, and dirt dug from its ditch was thrown over the vault even before the mortar had dried.

A diagonal fence was built contrary to property lines, passing over the drain and drawing the north end of the west shop into the realm of the armory. It is perhaps then that the shop became identified with tinsmithing. Late owner Mary Stith referred to it as "the tin shop" in her 1813 will.

Armory workers began discarding the waste from their work—coal clinkers, cast-off parts of weapons, a crucible containing brass—into the ravine, further covering the drain. Layers of the coal-bearing black waste built up within the fenced enclosure, along with garbage from the kitchen. Wartime strata contained bones from large cuts of beef, much of it boiled, contrasting with remains of the old tavern food. Half a dozen cattle hooves could suggest an unrefined diet or the production of neat's-foot oil for leather. Anderson accounts refer to purchase of "11 pairs of cows feet." Soon after 1782, the diagonal fence was removed, snips from tinsmithing and other waste were dumped into the postholes, and prewar property boundaries reestablished. Anderson returned to the site, once again bounded by a rectangular fence, and resumed blacksmithing, doing civilian work.

These and other activities left archaeological traces. One aspect of the armory project is the degree to which such traces can be found and read eighty years after the first investigator set shovel to dirt in Williamsburg. Discoveries of physical evidence for changes such as wartime disruption of the rectangular property grid can be combined with fresh perspectives on written documents to re-create lost settings. The fully crafted sites become more legible settings in which to experiment with and portray ways of life in the country's past.

Colonial Williamsburg's Shirley H. and Richard D. Roberts Director of Architectural History, Ed Chappell contributed to the winter 2010 journal "Exploring the Coffeehouse."