Promises to Pay, Promises Unkept

How We Won a War and Lost Our Shirts

Text by Richard G. Doty

Colonial Williamsburg Photography by Tom Green

Suppose you made your living in a town as a merchant. Suppose you were accustomed to using paper money for transactions large and small, there being few or no coins in circulation. Suppose that paper was promissory, pledging eventual redemption in coin. Suppose that currency had always proved a dependable medium of exchange.

Now suppose there was a war, and your side was losing. Suppose the enemy had taken towns nearby and was showing every inclination of taking yours. Suppose you were attempting to pay for your defense with the same medium you had always used. What do you suppose would happen? Would the value of your money fall? Where do you suppose it would land?

That state of affairs beset the generation of the American Revolution, three to four million souls scattered from Maine to Georgia. Perhaps a third were for independence. Perhaps another third were loyal to England. The other third tried to stay out of the way of the first two. Nearly everyone was affected by the paper money crisis because paper was the backbone of the colonial monetary system and now stood at the center of the insurgent one. How did this dependence on paper come about in the Age of Coins?

The English-American colonies were an economic success—except by the one measurement that at the time mattered most. They contained almost no natural gold or silver, the origins of wealth, the sinews of commerce. Lacking the material for making an orthodox money, they came up with one which was unorthodox. And they were the first people west of China so to do.

The colonists were expected to pitch in for the crown when England went to war. In 1689, the mother country embarked on the first in a series of conflicts with the French over who would rule North America. Shortly thereafter, authorities in Massachusetts were asked to raise and equip troops for service in Canada. Where would they find the money? There was no coinage in circulation, and the king wasn't likely to accept wampum or pelts—two of the more popular mediums of exchange—as Massachusetts's contribution to the war effort. What to do?

Why not print certificates? The British government had promised to pay back the colony in specie once it won the war. That would mean that the paper could be considered as good as gold—or silver. And since everyone knew that the paper was good, redeemable in hard cash at war's end, why not leave it in circulation? The Bay Colony would have a stable medium of exchange, and its people could buy and sell with increased confidence and ease.

It worked. So the other colonies got into the currency game, too. Massachusetts had produced the first public currency, as opposed to private banknotes, in the Western world. And she and her sisters were probably the first entities anywhere to depend upon it to the degree they did. But they had little choice. During the Age of Mercantilism, the whole point of colonies was to remit desirable products, not receive them—especially silver and gold, whatever the form. So if English America could not uphold her side of the bargain, that was a problem. But the crown had no intention or obligation to redress it, except in extraordinary circumstances. The colonists were on their own.

Though the first colonial paper was printed to fight a war, it was quickly seen for what it was, or could be: the greatest single boon that ever came our way. Currency could be circulated to pay for a lighthouse, as in the case of Georgia notes of 1769, which constructed one on Tybee Island, outside Savannah. And for relief of the poor, which the people in Philadelphia did the same year. Currency could pave the streets, erect more lighthouses—in short, make improvements for the general good and, incidentally, create money out of thin air.

From an American perspective, the system worked remarkably well for a remarkable length of time, the last eight decades of British rule. From a British perspective, the system was suspect. Precisely what did these hayseeds think they were doing? The king issued money, no one else. But the royal displeasure could be heard only faintly across three thousand miles of blue water.

When the colonists determined to leave the British Empire, they saddled their makeshift monetary medium with one more job: to pay for their war for independence. The concept was bold and risky. But provided the war was short, localized, and intermittent and did not demand great sacrifices, America's currency might stand up to the burden. Promissory notes could be printed and circulated, supplies purchased, armies paid, as in the old days. A quick victory would bring patriotic élan and an era of good feelings, buying time to find the coins to redeem the wartime currency. That was the hope, and that was the only option: the colonies were as coin poor in 1775 as they had been in 1675, or 1620, or 1607. Unless sympathetic foreigners offered to fight or pay for their war for them, Massachusetts, Virginia, New York, and all the others would have to print money.

In the process, they asked, why not add visual elements to the notes to tell a story about who we were, why we were fighting, what we expected to achieve—and how we were doing?

Such words and pictures had far more impact in the eighteenth century than they do in the message-rich twenty-first. The merchant in Charleston, South Carolina, or the farmer outside Litchfield, Connecticut, likely had no more than three or four sources of verbal or pictorial imagery—a Bible, a newspaper, a handbill, and a piece of currency.

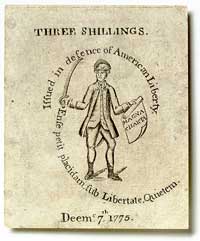

Americans were among the first people to put messages on paper money. Notes of Massachusetts from 1775 and 1776 are fine examples, documenting the shift and hardening of public opinion. A bill for three shillings of December 1775 depicts an American soldier, sword in hand, with the motto, curved over his head, "Issued in Defence of American Liberty." He bears a scroll with the words MAGNA CHARTA. The implication is clear: the soldier is fighting to defend the rights of free-born Englishmen, rights the thirteenth-century great charter enshrined. Within a year the soldier's scroll, seen on a thirty-six-shilling note from November 1776, calls for "Independance."

The artist was Paul Revere, a silversmith. Note engraver Thomas Coram was a painter, and Benjamin Franklin, who printed currency for Pennsylvania and other places for thirty years, had done everything. It was a country with many things to do and few people to do them.

Revere did engravings for Massachusetts and New Hampshire. Coram, who worked only for South Carolina, produced a series of images reminiscent of classical paintings and sporting elevating Latin legends. The back of his seventy-dollar bill shows an American eagle plucking at the liver of a chained English Prometheus. But Coram was apparently thinking over his loyalties even as he was creating the cuts; he would soon be in the enemy's camp.

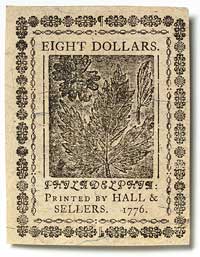

The money of the infant United States, Continental currency, had allegorical vignettes contained in a seventeenth-century book owned by Benjamin Franklin and apparently loaned to the printers Hall & Sellers for the occasion. The mottoes were apposite—provided you knew Latin and were conversant in the verbal and visual shorthand involved. An eight-dollar Continental note from 1776 is typical: we see a harp with the motto MAJORA MINORIBUS CONSONANT, which might allude to the strings of a harp but was more likely a reference to the importance of all states uniting. Not everyone got the high-minded pictures and words on the first take; the public requested, and got, guidance from the Philadelphia newspapers.

You could call Coram's design a political cartoon, albeit one of artistry. Baltimore silversmith Thomas Sparrow took visual expression further, though with more sincerity than skill. Sparrow's canvas was a series of Maryland notes of mid-1775. Crudely printed and poorly designed, his composition's required close scrutiny. All his denominations bore the same images. For the bills' faces, Sparrow chose a British fleet attacking an American city while King George attempts to set it afire and tramples on a scroll labeled M CHARTA. Next in line is Britannia, who is being handed a petition from Congress. America treads on a scroll marked SLAVERY and raises a liberty cap to cheer the troops rallying to her defense. Sparrow put his initials at bottom left.

The backs of his notes were less dramatic, more hopeful. They showed Britannia and America clasping hands and making peace, with the Latin motto PAX TRIUMPHIS POTIOR. Translated: Peace is Preferable to Victory. Sparrow signed this side in full, and added LIBERTY at upper right.

The messages depended in part on the means available for getting them out. Places like South Carolina could afford intaglio engraving. Places like Georgia or North Carolina might have to settle for simpler images, or simply words—in North Carolina's case, a series of short, pithy sayings, sometimes in Latin and other times in English, to bolster patriot morale and discourage the oppressor. A five-dollar bill from the darkest year of the revolution, 1778, reminded everyone that the war was "A Lesson to Arbitrary Kings, and Wicked Ministers."

What the money was worth diminished as the war went on. How could it have been otherwise? This is what the insurgents needed: a quick war, a localized war, a victorious war—with British repayment at the conclusion. This is what they got: a long war, a doubtful war, a war involving enemy occupation of cities and sections, sometimes repeatedly, sometimes for years—and no possibility that London would pay them for their time and trouble.

Continental currency held its own for the first two years. State issues held their own as well, although not for quite as long as national notes. In any case, if you had a dollar bill from the Continental Congress or from any of the states, you could expect to see it accepted at or near par through 1775, through 1776, and into the early part of 1777. But things began slipping after that.

An eagle representing America tore at a chained Prometheus, representing England on this South Carolina bill.

The slippage would occur because an impasse had been reached: while the British were never quite able to conquer the revolutionaries, the revolutionaries never came close to defeating the British. Nor did they succeed in evicting them from several important centers of population. Americans continued to accept national and state notes, but they would begin to discount them in light of the fortunes of war.

The autumn of 1777 was crucial: continuing American defeats led to a depreciation in all jurisdictions, of all paper, by October. The depreciation was minor in several cases: nobody would raise serious objections if it took $1.10 in Continental currency to purchase one Mexican dollar in silver. But someone in Maryland or Virginia would be sure to complain when it took three dollars in paper from those states to buy that same silver dollar. And things went rapidly downhill.

The Americans were in a double bind. The war went on and on. The value of paper currency went down and down. But the war also got wider and wider, and therefore cost more and more money in absolute terms, regardless of the means of payment. Under such circumstances, currency systems can collapse. Under such circumstances, ours did.

By the spring of 1780, Continental currency was trading at one-fortieth its face value. It took forty dollars in Continental notes to purchase one Mexican dollar—if you could find anyone naive enough to make the sale. The best of the states' monies had suffered the same depreciation. The worst were, well, far worse. North Carolina's money functioned at a sixty-to-one discount, as did that of Pennsylvania and Virginia. By the end of the following year, Virginia's money was worth one-thousandth of what it said it was worth, and North Carolina's was not much better. They were printing two-thousand-dollar bills in Williamsburg in the middle of 1781.

By that point, the states had issued a quarter billion dollars in paper, currency supported by nothing more substantial than the vague hope of an eventual redemption. The national authorities had issued a like amount, with a like guarantee. In the early spring of 1780, the Continental Congress decided to deal with the paper plethora by . . . another issue of paper money.

But this one would be different. This issue would consist of bills circulated by the states, exchangeable for Continental currency at a rate of forty to one, the value ratio the national notes now enjoyed against the piece of eight. About half of the states joined the scheme. The other half were unwilling or were occupied by British troops. In this way, more than $111,000,000 in national currency was pulled from circulation—a fair amount of state currency was lured in by the same law—and destroyed. Much more was retired in exchange for federal bonds. But it would take a new government to accomplish that. And from the number of Continental and state notes which still surface on occasion, it is apparent that many of our citizens, having, as they saw it, been burned once, were twice shy about turning in the paper. They squirreled it away in hopes of a better deal that never came.

The war for independence was won in spite of our money rather than because of it. But two and a quarter centuries have mellowed our appreciation of the situation, have cast romantic shadows over it, shadows which an earlier generation would not have seen. What it saw was that our money of necessity and choice had failed us when we needed it most and that public currency was to be avoided at all costs. And so it was—until another crisis as dire as the first caused us to look again, and to reconsider. That was the Civil War, and out of it a modern nation, and a modern money, would be born.

North Carolina put arbitrary Kings and wicked Ministers on notice with this hand-signed bill in 1775. View detail

Richard G. Doty is curator in the Numismatics Division of the National Museum of American History, Smithsonian Institution. He is the author of works on American coinage and coining techniques. This is his first appearance in the journal.

The currency illustrated from Colonial Williamsburg's collections is the gift of Mr. and Mrs. Joseph R. Lasser of New York.