Online Extras

Extra Images

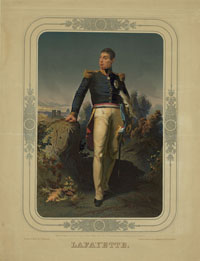

Library of Congress

A print after a painting of Lafayette by Ary Scheffer from 1824, the year he returned to the United States.

He Revisits the Home Won by His Valor

by Alexander Chesterfield

“The City of Williamsburg— May her happiness become equal to the grateful remembrance of an American patriot and the affectionate wishes of an old friend.”

—Marquis de Lafayette

Between autumn 1781, when the Comte de Rochambeau’s victorious Yorktown troops quartered in Williamsburg, and spring 1862, when General George McClellan’s Army of the Potomac occupied the Union-vanquished city, there had been in Virginia’s former colonial capital an event of no greater moment than the return of Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier the Marquis de La Fayette. Not that it got much notice from anyone else.

For the second time since the Revolution, Lafayette traveled to America, in 1824, now at President James Monroe’s invitation, and before departing the following year, trekked more than 6,000 miles among the republic’s twenty-four states. The nation was eleven states larger than during Lafayette’s first victory lap in 1784.

Williamsburg was a convenient place for him to linger for a couple nostalgic nights on the way from Yorktown, where he was guest of honor at a three-day, dignitary- studded anniversary celebration of Lieutenant General Charles Earl Cornwallis’s defeat, to Hampton Roads, where four days he basked in the admiration of Norfolk and Portsmouth.

It took Lafayette’s traveling secretary, Auguste Levasseur, 492 pages and two volumes to chronicle their national excursions. He devoted less than a paragraph of Lafayette in America in 1824 and 1825; or, Journal of a Voyage to the United States, to the Williamsburg stop. It read in part:

On the morning of the 20th, we departed for Williamsburgh, formerly the capital of Virginia, but at present a small town retaining very little of its ancient importance. Its college which was founded under the reign of William and Mary and bears their name, was celebrated for the excellence of its learning until within about half a century, since when it appears to have partaken of the sad destiny of the town, to which it belongs. Williamsburg is situated on a plain between York and James rivers. . . . Although the population of Williamsburg is not more than 14 or 1500 souls the general was received with great feeling, and had the pleasure of greeting a considerable number of ancient friends.

Major General Lafayette had last sojourned at Williamsburg in 1781 after General George Washington posted him to Virginia to harass the British rummaging around the Old Dominion for a place to fortify. Cornwallis ambushed and embarrassed the young Frenchman at Green Spring as the invaders quit Williamsburg for Portsmouth by way of Jamestown in July.

Portsmouth not to their liking, the free-ranging redcoats entrenched at Yorktown in August while Lafayette watched from West Point upriver. Washington and Rochambeau set out from New England to trap the enemy in its works, and by his twenty-fourth birthday in early September the marquis was waiting for them outside Williamsburg. Lafayette greeted Washington near the college President’s House on the road from Richmond when the commander in chief arrived September 14.

Washington made his headquarters at George Wythe’s house and Rochambeau with Lafayette at Peyton Randolph’s, where he would sleep again forty-three years later. After winning the siege, Rochambeau and his troops wintered in the city, lending it some of the joie de vivre lost when Virginia’s government moved to Richmond the year before.

Told for more than a century were tales of the new egalitarianism of those days, which so flourished that balls, once affairs of the gentry, convened out of doors for all to enjoy. An anecdotalist penned “a pretty story showing the spirit of the hour” of a Palace Green dance in which French officers joined. Mary Cary dropped her handkerchief. Rochambeau picked it up “and with the gallantry of the Frenchman” returned it on bent knee. He said to her, “What would the fair ladies of France say could they see the Count de Rochambeau in such a posture before an American belle?” Swiftly came the reply: “Should the ladies of France think as little of it as does Miss Cary, they would say nothing at all.”

Remember this because she turns up later a few paragraphs below at a dance with another Frenchman.

For the 100th anniversary of the victory, when a railroad ran down Duke of Gloucester Street for the celebrants and the Peyton Randolph house had passed into the Peachy family, Richmond’s Robert Ward compiled General La Fayette in Virginia, in 1824 and ’25: An Account of His Triumphant Progress Through the State. Ward gave a more fulsome account of the Williamsburg appointment than Levasseur, yet it ran but four paragraphs in the book’s 136 pages. Elsewhere, he spent a paragraph on the sights an advance party saw in the city.

Lafayette set out from Yorktown in a barouche at 2 p.m. Wednesday—after the speeches were done and he had dined—attended by VIPs.

He arrived at Williamsburg at 6 o’clock, amidst merry peals of bells and the congratulations of its citizens. He was conducted to the residence of Mrs. Mary Monroe Peachy, which had been volunteered for his accommodation by that patriotic lady, where he was received by the Mayor and civil authorities, with an eloquent address, delivered by Mr. Robert Anderson, to which he made a neat and appropriate address, as follows:

“Your affectionate welcome, and the honorable expressions of your esteem, are the more gratifying to me, as I remember my old personal obligation to this seminary, the parent of so many enlightened patriots who have illustrated the Virginian name. Here, sir, were formed, in great part, the generous minds whose early resolutions came forth in support of their heroic Boston brethren, and encouraged the immortal Declaration of Independence, so much indebted, itself, to an illustrious Virginian pen. Those, and many other recollections, such as the efforts made by a colonial assembly of Virginia, in times still more remote, to obtain from the British Government the abolition of the slave trade, inspire a great respect for the college, where such sentiments have been cherished. I am sensible of the honor conferred on me by the adoption you have been pleased so kindly to announce, and I beg you, sir, and the other gentlemen of the college, to accept my most grateful thanks.”

After visiting our college, and going to pay his respects to Mrs. Page, the widow of the late Governor Page, he sat down to dinner at the Raleigh Tavern, at which Colonel Bassett presided . . . at which there were many distinguished gentlemen—the Governor and Council, Chief Justice Marshall, John C. Calhoun, Generals Taylor, Macomb. . . .

On Friday morning, the General left Williamsburg, at l0 o’clock, for Jamestown.

A tradition among the descendants of Revolutionary War veteran, lawyer, and judge St. George Tucker, who was too frail to travel from his farm to participate, is that the Peachys borrowed his new bed from his Courthouse Square home for Lafayette’s comfort, and that the Raleigh, which stood empty and dilapidated, was quickly spruced up and filled with borrowed furniture for the dinner in his honor.

Among the Tucker clan was Cynthia Beverley Tucker Coleman. Near the end of her seventy-six years, she sat to write The Annals of Williamsburg, tracing stories of the city on the lined pages of a notebook in ink now browned with age. The college now preserves it. She was born January 18, 1832, in Saline County, Missouri, to lawyer and jurist Nathaniel Beverley Tucker and Lucy Ann Smith Tucker, who returned to town in 1837.

Cynthia Beverley Tucker Coleman, a remarried widow who bore seven children, took refuge in Richmond, waited for the Yankees to leave, returned to principal the Female Seminary of Williamsburg, and in 1884 organized the city’s first preservation effort, a Sunday school group that repaired broken ancient tombstones. She co-founded Preservation Virginia at her Tayloe House in 1889, saved the Magazine from collapse, and secured the Capitol’s foundations and the Publick Gaol. In 1900, she started her never-finished Annals, filling the final four of her sixty-eight pages with twenty-five paragraphs on Lafayette’s acceptance of the town’s invitation to return to Williamsburg. He arrived Wednesday afternoon, October 20.

Here preparations for his suitable reception had been in progress since September, all classes entering into a friendly competition to do him honour. A Committee of arrangements was formed. On the part of the Common Hall Dr. Jessie Cole, Robert Anderson and Dr. Thomas Griffin Peachy. On the part of the citizens Messrs. Tunstall Banks, John Blair Peachy and Dr. Samuel Stuart Griffin. Acting in unison right nobly did they perform their mission. Mrs. Mary Monroe Peachy (née Cary of Rochambeau memory) had offered her house for the occasion, other patriotic women begged to contribute to the adornment of his sleeping apartment. One sent a new mahogany bedstead another a dressing table and so on. These things used for a night by Lafayette have been handed down as precious relics of the Nation’s guest.

Accompanied by the Governor, James Hampden Pleasants, the Executive Council, The principal Judges of the State and Chief Justice Marshall, The Minister of War John C. Calhoun, Officers of the Army and Navy, escorted by Cavalry Companies, from Richmond, Petersburg and New Kent County and Williamsburg, the cavalcade reached its destination in a rain. The intended illumination of the Town and some minor parts of the programme were necessarily modified. The crowd assembled on Court House Green had to seek shelter in the neighbouring houses. The addresses of Welcome were made not on the Green as originally intended, but from the porch of Mrs. Peachy’s house. That historic colonial porch has in these latter days given place to a tawdry gimcrack affair which is an offense to the eye and to good taste.

After Lafayette had made a suitable and appreciative reply to the expressions of good will and admiration which met him on every hand, the whole party adjourned to the spacious drawing room with its wainscoted walls and marble mantle near the ceiling over the capacious fire-place. Here under the light of an hundred candles, which softened the smiles of the beautiful women, Genl. Lafayette held a reception. . . . “Abundant refreshments were served around” but their character has not been preserved. At ten o’clock the guests dispersed and left the weary traveler to seek repose under the canopy of the high-post bed-stead almost as difficult to scale as the redoubt at York Town. The next morning was spread for him an old Virginia breakfast, with its variety of breads, its oysters, and it game. Most of the strangers in the city partook of this “feast of fat things.” At twelve o’clock the party visited William and Mary College where they were received by the President Dr. Augustine Smith and the professors. An elegant address of welcome was delivered by the President, so says the chronicler of the time. It was intended that even the Sunday school children should take part in the pageant. A poem written by Miss Elizabeth Griffin Gatliff was to have been spoken by the ten year old daughter of Dr. Smith. Miss Mary D. Smith, recently of New York said, “I was but a shy child and at the last my heart failed me.” The poem was left unsung. . . . “My sister and I were introduced by Col. Burwell Bassett—a nephew of Mrs. Washington—to Genl. Lafayette, who shook hands with us, an honour I more fully appreciated in after years than I did at the time.”

General Lafayette charmed his hearers by his encomiums on the College. There he held another reception and at two o’clock visited Col. Bassett at Bassett Hall, which still retaining the old name is now the interesting and charming home of Mrs. Israel Smith formerly Miss Rebecca Minturn of New York City. . . .

At five o’clock the party sat down to dinner in the Apollo Hall of the Raleigh Tavern. Besides the citizens about forty strangers were entertained on this occasion. The worthy chronicler says of this dinner, “Morally and physically considered it was perhaps, the richest and most delightful ever enjoyed in Williamsburg. The dessert was uncommonly rich and elegant, the fruits and wines the best that could be procured.” The entertainment was enlivened by a variety of airs from the band of the Petersburg Volunteers. Doubtless the haunch of venison, the saddle of mutton and surloin of beef were a startling revelation to the frugal Frenchmen of frog-eating France.

Some of the toasts drunk with much feeling and display of sentiment, though more than a trifle bombastic, are not without interest. As being the first in importance for such an occasion: — “Our illustrious guest, Genl. Lafayette who in the morn of his life embarked upon the tempestuous sea of American liberty and unappalled by the vivid lightning of British wrath, and the awful thunders of her power, magnanimously aided in conducting the almost shipwrecked ark of our newly reconstructed National Independence into the secure and tranquil haven of peace and happiness.”

General Lafayette immediately after gave the following:

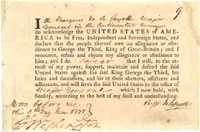

“The City of Williamsburg—May her happiness become equal to the grateful remembrance of an American patriot and the affectionate wishes of an old friend.”

General Macomb toasted John Marshall:

“The Chief Justice of the United States as distinguished for his legal abilities as for the possession of pre-eminent genius, unblemished integrity, and the exalted confidence of his Country.”

Chief Justice Marshall’s toast in reply:

“The City of Williamsburg. Long the seat of government, it still remains the seat of science, of hospitality and good feelings.”

Hon. John Tyler’s toast (afterwards President of the United States): “Our fellow citizen Gen. La Fayette adopted by Virginia, he revisits the home won by his Valour.”

By John C. Calhoun—Secretary of War:

“The College of William and Mary and her illustrious sons.” . . .

In those days of chivalry no public occasion was perfect without a toast to woman:

“The American fair. Freemen as are we delight in the soft fetters of which their native charms import and kiss the light and tender pressure of the chains we wear. . . .”

The entertainment of Genl. Lafayette in Williamsburg closed with a ball in the Apollo Hall, which was opened by the Gallant Frenchman with the winsome and fascinating wife of Dr. Thomas Griffin Peachy.