Online Extras

The British Herbal Slideshow

Uncommon And Expensive

text by Mary Miley Theobald

photography by Barbara Lombardi

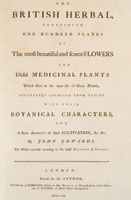

There may be no better guide to the plants that grew in eighteenth-century gardens than The British Herbal, a rare collection of botanicals by artist John Edwards, published in 1770. “It’s one of the most valuable books we have,” said Wesley Greene, garden historian in Colonial Williamsburg’s historic trades department. “It lets us document the sort of plants that were available in the colonial era.” Edwards referenced Linnaeus for every plant, allowing Greene and others to identify species precisely.

An herbal is a book about plants and their medicinal properties. Edwards’s volume provided little to enlighten an eighteenth-century physician. For many entries, he gives no medical information. When he does, it is minimal. Nightshade, he wrote, has “Berries which are useful in Medicine.” Edwards was, however, among England’s leading botanical artists, and his flowers have a vibrant realism.

His flower designs were much appreciated by the calico-printing industry of his day, which had centers in the places he lived, in London and Surrey, just south of London. It seems likely that his income derived more from the fabric industry than from the sale of his two botanicals, The British Herbal and A Collection of Flowers.

Historians know John Edwards was born in 1742, but records show at least seventy-two babies of that name born in England that year. The artist is almost certainly the John Edwards delivered in London to John Edwards, a vintner, and apprenticed at fifteen to a member of the Painters and Stainers Company, a guild formed in the 1200s. During his seven-year apprenticeship, he learned the mysteries of painting and engraving. Within two years, he had won his first award from the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufacturers, and Commerce. From the age of twenty-one, he displayed his artwork at such London exhibitions as those of the Society of Artists and the Royal Academy.

In his late twenties, Edwards took on his first apprentice—he had at least four more—and became a liveryman of the Painters and Stainers, entitled to wear the livery of his guild and to other guild privileges. Although there is no record of a wife, he must have married around that time. He had at least one son, also named John Edwards, whom he apprenticed to himself in 1783, but the boy was soon turned over to a citizen-draper in the fabric business for the rest of his education.

Edwards’s herbal, reissued in 1775, contains illustrations of such flowers as the apple blossom, tulip, wild roses, and viola tricolor, common in England and in the American colonies. The British Herbal, however, was not common. Expensive to produce, it had one hundred hand-colored illustrations, a sampling of which is reproduced here.