Bilboes, Brands, and Branks

Colonial Crimes and Punishments

by James A. Cox

The English-American colonies were autocratic and theocratic, with a patriarchal system of justice: magistrates and religious leaders, sometimes one and the same, made the laws, and the burden of obeying them fell on the less exalted—the tradesmen, soldiers, farmers, servants, slaves, and the young. That burden could be weighty.In his History of American Law, Lawrence M. Friedman wrote, "The earliest criminal codes mirrored the nasty, precarious life of pioneer settlements." A good example is the set of statutes imposed on Jamestown, the "Articles, Lawes and Orders Diuine, Politique, and Martiall for the Colony in Virginia," by the Virginia Company of London in 1611. They were, with some justice, described by the colonists in a letter to the crown in 1624 as "Tyrannycall Lawes written in blood." They said:

The cause of the vniust and vndeserved death of sundry . . . by starveinge, hangeinge, burneinhge, breakinge upon the wheele and shootinge to deathe, some (more than halfe famished) runninge to the Indians to gett reliefe beinge againe retorned were burnt to deth. Some for stealinge to satisfie thir hunger were hanged, and one chained to a tree till he starved to death; others attemptinge to run awaye in a barge and a shallop (all the Boates that were then in the Collonye) and therin to adventure their lives for their native countrye, beinge discovered and prevented, were shott to death, hanged and broken upon the wheele, besides continuall whippings, extraordinary punishments, workinge as slaves in irons for terme of yeares (and that for petty offenses) weare dayly executed.

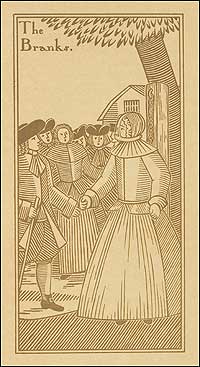

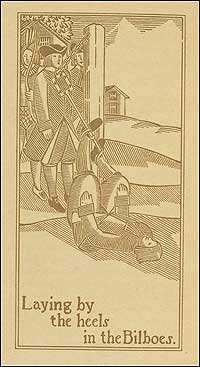

Alice Earle's 1896 Curious Punishments of Bygone Days

showed readers what bilboes did to the legs of lawbreakers.

Every Virginia minister was required to read the "Articles, Lawes and Orders" to his congregation every Sunday, and, among other things, parishioners were reminded that failure to attend church twice each day was punishable in the first instance by the loss of a day's food. A second offense was punishable by a whipping and a third by six months of rowing in the colony's galleys. Which underlines the notion of the law as an arm of religious orthodoxy.

As Friedman says, an attempt to generalize about all the colonies during the 169 years between the founding of Jamestown and the Revolution—the number of years that passed between independence and Hiroshima—would be bootless. But common threads can be traced, and laws concerning religion, as well as the severity of punishments, are as good a place to start as any.

In the Puritan north a religious message leaps out from almost every page of the early criminal codes. Sin, of course, existed in the eyes of the beholders, and the eyes were everywhere—as you might expect in small, inbred communities. Consider the scrutiny given to observance of the Sabbath. The law usually required churchgoing, and someone was always checking attendance. In early Virginia, every minister was entitled to appoint four men in his fort or settlement to inform on religious scofflaws.

In the early seventeenth century, Boston's Roger Scott was picked up for "repeated sleeping on the Lord's Day" and sentenced to be severely whipped for "striking the person who waked him from his godless slumber."

Virginia law in 1662 required everyone to resort "diligently to their parish church" on Sundays "and there to abide orderly and soberly," on pain of a fine of fifty pounds of tobacco, the currency of the colony. Colonial strictures on deportment in the pews long applied, even to children, such as in 1758 when young Abiel Wood of Plymouth was hauled before the court for "irreverently behaving himself by chalking the back of one Hezekiah Purrington, Jr., with Chalk, playing and recreating himself in the time of publick worship."

In l668 in Salem, Massachusetts, John Smith and the wife of John Kitchin were fined "for frequent absenting themselves from the public worship of God on the Lord's days." In l682 in Maine it cost Andrew Searle five shillings merely for "wandering from place to place" instead of "frequenting the publique worship of god."

And woe to the man who profaned the Sabbath "by lewd and unseemly behavior," the crime of a Boston seafaring man, one Captain Kemble. He made the mistake of publicly kissing his wife on returning home on a Sunday after three years at sea, a transgression that earned him several hours of public humiliation in the stocks.

But, of course, the codes concerned themselves as much with the secular as the divine. The laws, especially in New England, made crimes of lying and idleness, general lewdness and bad behavior.

Sex was of particular concern. Outlawed were masturbation, fornication, adultery, sodomy, buggery, and every other sexual practice that inched off the line of straight sex as approved by the Bible. The term "sodomy" was applied to homosexual behavior; "buggery" to bestiality.

Punishment for such serious sexual crimes could be severe. Thomas Granger of Plymouth, a boy of seventeen or so, was indicted in 1642 for buggery "with a mare, a cow, two goats, five sheep, two calves and a turkey." Granger was hanged; the animals, for their part in the affair, were executed according to the law, Leviticus 20.15, and "cast into a great and large pit that was digged for the purpose for them, and no use was made of any part of them."

In 1642, Edward Preston was sentenced to be publicly whipped at both Plymouth and Barnstable "for his lewd practices tending to sodomy with Edward Mitchell, and pressing John Keene thereunto (if he would have yielded)." Keene, who had reported the crime, was required to watch the punishment because he was suspected of "not being without fault himself." No death penalty here, since the actions of Preston and Mitchell only "tended toward sodomy."

In Crime and Punishment in American History, Friedman writes:

In the eighteenth century, the death penalty was invoked less frequently for these crimes. Even in the seventeenth century, most sexual offences were petty, and the punishment less than severe. Mild—but amazingly frequent.The thousands of cases of fornication and other offenses against morality . . . seem to give the lie to the conventional picture of life in colonial times: sour, dour, obsessed with religion. . . . A frank and robust sexuality leaps from the pages of the record books. Still . . . most people probably did not transgress.

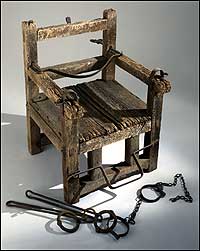

A seventeenth-century English ducking stool, in the Colonial Williamsburg collections, would be swung out at the end of beams over a river or pond. Some dunked died. - CWF Collection

Behind most of the systems of justice in early civilizations lay the concept of vengeance, making the miscreant pay for his crime. A side benefit to this idea was deterrence—giving other would-be offenders a good reason to stay on the straight and narrow. Colonial practice took the matter a step further, making use of shame and shaming. Punishments were almost always public, for the aim was to humiliate the wayward sheep and teach him a lesson so that he would repent and be eager to find his way back to the flock. Nothing made a colonial magistrate happier than public confessions of guilt and open expressions of remorse.

The records tell of hundreds of colonial sinners forced to sit in the stocks in public view. After warnings and fines, this was one of the mildest punishments, although the scorn of bystanders, not to mention the garbage and worse hurled at the miscreant by fellow citizens, made for uncomfortable moments. At times, the punishment was tailored to fit the crime, so that nobody missed the point. Thus, when a servant named Samuel Powell stole a pair of breeches in Accomack County, Virginia, in 1638, he was sentenced to "sitt in the stocks on the next Sabboth day . . . from the beginninge of morninge prayer until the end of the Sermon with a pair of breeches about his necke."

Colonial villages were enjoined to have their own sturdy stocks, and those that were lax ran the risk of a fine. The magistrates in early Boston had imported from England bilboes, long heavy bars of iron with sliding shackles and padlocks that held many a colonial culprit by the heels. When replacements became needed, it dawned on the local pence watchers that iron was expensive and in short supply, though wood was plentiful. A set of wooden stocks was ordered, and as soon as the job was done, the magistrates selected as their first customer Edward Palmer, who was "fyned £5 & censured to bee sett an houre in the stocks." Carpenter Palmer's crime? He was accused of extortion for charging £1 13s. 7d. for the wood and his labor in building the stocks.

Most self-respecting settlements also had a ducking stool, a seat set at the end of two beams twelve or fifteen feet long that could be swung out from the bank of a pond or river. This engine of punishment was especially assigned to scolds—usually women but sometimes men—and sometimes to quarrelsome married couples tied back to back. Other candidates were slanderers, "makebayts," brawlers, "chyderers," railers, and "women of light carriage," as well as brewers of bad beer, bakers of bad bread, and unruly paupers. In the absence of a proper ducking stool, authorities in some climes, as in Northampton County, Virginia, ordered the offender "dragged at a boat's Starn in ye River from ye shoare and thence unto the shoare again."

Perhaps the cruelest punishment for slanderers, nags, and gossips, when simple gagging wasn't enough, was the brank, sometimes called the "gossip's bridle" or "scold's helm." This was a sort of heavy iron cage, that covered the head; a flat tongue of iron, sometimes spiked, was thrust into the mouth over the criminal's tongue. Less sophisticated areas made do with a "simpler machine—a cleft stick pinched on the tongue." Either system pretty much insured silence.

Most village squares boasted, along with a church, a whipping post as well as stocks and other engines of correction. Larger municipalities often had whipping posts at convenient spots in the city, and sometimes a cart substituted for the post so that the evildoer could be dragged from location to location, tied to the "cart's-arse," for the education and edification—and entertainment—of the populace.

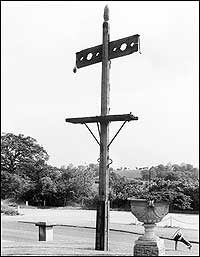

Fifteen feet high, this pillory and post—from seventeenth-century England and in the Colonial Williamsburg collections—held the offender by the neck and hands.

Whipping sentences usually stipulated that the stripes be "well laid on," as the phrase went. In one case of a multiple whipping, the beadle—a minor church official—was ordered to lay on, but was so light-handed the sheriff seized the lash and scourged him, too, before turning to the prisoners. Bystanders gave the sheriff three cheers for his attention to duty.

The pillory, or "stretch-neck," called "the essence of punishment" in England, stood in the main squares of towns up and down the colonies. An upright board, hinged or divided in half with a hole in which the head was set fast, it usually also had two openings for the hands. Often the ears of the subject were nailed to the wood on either side of the head hole. In 1648 in Maryland, John Goneere, convicted of perjury, was "nayled by both eares to the pillory 3 nailes in each eare and the nailes to be slitt out, and whipped 20 good lashes."

The device was described by Nathaniel Hawthorne in his Scarlet Letter as an "instrument of discipline so fashioned as to confine the human head in its tight grasp, and thus hold it up to public gaze. The very ideal of ignominy was embodied and made manifest in this contrivance of wood and iron. There can be no outrage, methinks . . . more flagrant than to forbid the culprit to hide his face for shame."

The pillory was employed for treason, sedition, arson, blasphemy, witchcraft, perjury, wife beating, cheating, forgery, coin clipping, dice cogging, slandering, conjuring, fortune-telling, and drunkenness, among other offenses. One man was set in the pillory for delivering false dinner invitations; another for being the author of a rough practical joke; another for selling a harmful quack medicine. All sharpers, beggars, vagabonds, and shiftless persons were in danger of being pilloried. On several occasions, onlookers pelted the pilloried prisoner so enthusiastically with heavy missiles that death resulted.

Often the pillory was just part of a package of punishments. On April 23, 1771, the Essex Gazette of Newport, Rhode Island, reported that "William Carlisle was convicted of passing Counterfeit Dollars, and sentenced to stand One Hour in the Pillory on Little-Rest Hill . . . to have both ears cropped, to be branded on both cheeks with the Letter R (for Rogue), and to pay a fine of One Hundred Dollars and Cost of Prosecution." It could have been worse. Continental paper money usually carried this line: "To counterfeit this bill is Death."

Branding and maiming may shock us, but, Friedman says, for our colonist ancestors, "the sight of a man lopped of his ears, or slit of his nostrils, or with a seared brand or great gash in his forehead or cheek could not affect the stout stomachs that cheerfully and eagerly gathered around the bloody whipping-post and the gallows." In New England Jesuits and Quakers were particularly feared as "blasphemous Hereticks" for their "devilish opinions" and were banished, with orders never to return. The penalties for coming back were ears cut off, tongues bored through with a hot iron, and whipping until the blood ran.

Hogarth depicted a hanging at Tyburn's Tree in London. Such events could bring as many as 50,000 spectators. - CWF Collection

Burglary was punished in all the colonies by branding with a capital B in the right hand for the first offense, in the left hand for the second, "and if either be committed on the Lord's Daye his Brand shall bee sett on his Forehead as a mark of infamy." In Maryland, every county was ordered to have branding irons, with the lettering specifically prescribed: SL stood for seditious libel and could be burned on either cheek. M stood for manslaughter, T for thief, R for rogue or vagabond, F for forgery. In Maryland and Virginia a hog stealer was pilloried and had his ears cropped. For a second offense he paid treble damages and was burned with the letter H on his forehead. Double punishment if the hog stealer was a slave. The third offense brought death.

As vicious as colonial punishments were, there was a relatively simple way to avoid the worst of them, the gallows, by pleading "benefit of clergy." This escape hatch dated from the Middle Ages and applied to anyone who could read a certain passage from the Bible. It was always open to a particular page, the first lines of Psalm 51: "Have mercy upon me, O God, according to thy loving kindness: according unto the multitude of thy tender mercies blot out my transgressions." The original tilt was in favor of priests and monks, since most laymen could not read.

By colonial times everyone—male, female, even slaves—was using what had come to be called the "neck verse" to get off. Not that they had all learned how to read. But even the dullest magistrates finally came to realize that with a little work almost any fool could memorize the Good Book's magical formula.

And any man or woman unfortunate enough to stand in his dock could understand that if there was in English America a severe side to law and religion, there was as well a merciful.

View a slideshow of colonial punishments.

Pennsylvania writer Jim Cox contributed to the winter 2002-2003 journal a story on Patrick Henry's "Liberty or Death" speech.