Online Extras

Civil War Jamestown Slideshow

Library of Congress

Union soldiers with a bombproof at Fort Burnham, formerly the Confederate Fort Harrison

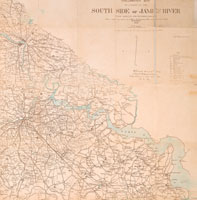

Virginia Historical Society

1864 map of the James, with the Confederate capital on the far left and Jamestown Island on the right.

Virginia State Library

The Ambler House at Jamestown, which Allen moved into early in the Civil War while he oversaw defense of the island.

Civil War Jamestown

Defending the Confederacy at Fort Pochahontas

by W. Barksdale Maynard

Few American archaeological digs garner as much attention as Historic Jamestowne’s. Since the 1994 discovery of the footings of one of the James Forts built by England’s 1607 Virginia colonists, investigators have been uncovering the postholes of its palisades and earth-fast buildings, its forgotten graves and broken crockery, its trash pits and butchered bones—clues about the culture of that place in that time. To find them, they had to excavate part of another of Jamestown Island’s strongholds, Fort Pocahontas, an earthen rampart the Confederate States of America shoveled up on the same strategic acre more than 250 years later. For a few months, that bastion helped guard the James River and the eastern approaches to the rebel capital, Richmond, about sixty miles above.

Named for a daughter of Powhatan, paramount leader of the Tidewater Indian chiefdom when the colonists arrived, Fort Pocahontas anchored the southern end of a line of fortifications and redoubts that stretched across Virginia’s lower peninsula to Fort Magruder outside Williamsburg and northeast to the York River. Commanding fields of fire up and down James River make Jamestown a natural position for fortification, site of a succession of brush, timber, masonry, and earthen breastworks. In the minds of the early Virginia settlers, Spanish galleons and Dutch men-of-war were the threats; at the opening of the War between the States, the Union navy was the danger. The National Park Service, responsible for most of modern Jamestown Island, says, “In 1861 Confederates initially regarded it as the best defensive point along the James River for defending Richmond, the South’s capital and industrial center.”

Today an undulating series of grassy mounds studded with gnarled cedar trees, Fort Pocahontas rose on James Fort traces. Jamestown Rediscovery archaeologists, led by William Kelso, have removed nearly half the Confederate overburden, and found such relics of the Southern rebellion as a collapsed powder magazine and a bombproof, twelve feet wide and at least eighteen feet deep. An underground, timber-lined shelter against bombardment, it still contained beams of a wooden roof and sandbag markings.

When the hostilities started, Jamestown Island was more than 1,500 rolling and mostly vacant acres of farm fields, swamps, marshes, and landings dominated by the circa-1750 Ambler House, owned by William Orgain Allen. In the 1860s, when wealth was measured in slaves, among other things, Allen had 800 and was among Virginia’s richest men, the scion of a seventeenth-century Southside, multimansioned Surry County clan. From upriver Claremont Manor, he controlled 300,000 plantation acres spread through three counties, as well as lumber and shipping enterprises, and a railroad. An Allen overseer supervised the toil of Jamestown Island’s field hands from the two-story brick Ambler place. The home had burned during the Revolution and, though rebuilt to its Georgian form, was by then decaying. Some aboveground reminders of Jamestown past remained, most noticeably the ruins of a circa-1690 church tower, and an adjacent graveyard. Plows turned up seventeenth-century debris, tokens of the days when James Fort was all Jamestown amounted to, as well as fragments of the colony’s first capital and of the village it grew to be. When Virginia’s government moved to Williamsburg in 1699, the town began to wither.

Allen had hesitated to allow a military encampment on the island in 1857 for the Jamestown 250th anniversary celebration lest they trample his crops. With the outbreak of war in April 1861, he sacrificed his harvest to the building of defenses, moved into the Ambler House, and put soldiers, free blacks, and his slaves to picks, shovels, and wheelbarrows. Sometimes they found such debris as broken pieces of seventeenth-century firearms. Allen raised troops at his expense to garrison the island to deny the river above to Union gunboats and access to the Confederate seat of government. The Federals controlled Fort Monroe thirty-five miles downstream at a Hampton Roads chokepoint, and risk of a Union naval assault from Yankee flotillas riding beneath Monroe’s guns was palpable: the Old Muddy James was a broad brown highway to Richmond.

Allen took a captain’s commission in the Jamestown heavy artillery. Off duty, he entertained fellow officers with vintage liquor and displays of Jamestown artifacts. General Robert E. Lee, at the time senior military advisor to President Jefferson Davis, toured the island in June. By then it garrisoned 1,000 soldiers manning twenty cannon aimed toward the river—at Jamestown, about a half to three-quarters of a mile wide. Fort Pocahontas, the guns of which could fire a sixty-five-pound shell about four-fifths of a mile, stood west of the church tower on a point. Four more earthworks rose around the island, some of their brushy battlements today visible in the island’s overgrown woods. Naval Lieutenant Catesby ap Roger Jones—his name denoting Welsh descent—had charge of their design.

The Union found no occasion to test his handiwork. General George B. McClellan launched the Union’s campaign on Richmond neither up the James nor up the York, but overland, up the Peninsula, in April 1862. Burning Fort Pocahontas's magazines and gun carriages, the Confederates abandoned the island May 3 for a position further west. Yorktown fell the fourth, Williamsburg the fifth. Union gunboats passed upriver with no annoyance from Jamestown Island.

Virginia born, Jones served in the United States Navy before the war and was a gunnery expert. Through him, Fort Pocahontas came to be involved with the ironclad CSS Virginia, of which he was executive officer and which he commanded when it dueled the USS Monitor in the James off Newport News. Confederate engineers built Virginia from the burned remains of the steam frigate USS Merrimack, aboard which Jones served in 1856 as ordnance officer, and which the Union scuttled when it abandoned the Norfolk Navy Yard in 1861. The idea of ironclad warships was novel, and nobody knew how thick their metal plates had to be to deflect cannon shot. Had tests been undertaken where Virginia’s plates were rolled, Richmond’s Tredegar Ironworks, journalists or spies might have reported the results. Jones experimented at rural, secluded Fort Pocahontas instead.

The fort’s Columbiads, cannon widely used in the war, blasted eight-inch shells at a model of the Virginia’s walls built of oak and pine and covered in plate. Jones found three-inch thicknesses were too little. Virginia got four—behind which she and her crew, Jones standing in for her wounded captain, battled Monitor to a draw March 9, 1862.

Jump ahead a century and a half. Archaeologist Kelso found fragments of this kind of eight-inch Civil War shell and hundreds of spikes that once fixed the wooden-plank floors of Fort Pocahontas’s gun emplacements, tokens, perhaps, of the testing of Virginia’s design.

Archaeology shows how Allen's crews raised Fort Pocahontas. To create the earthworks, the laborers scraped off the top few feet of the site’s soil and piled the dirt high to create a berm. The grading erased, or at least scrambled, near-surface traces of James Fort’s southern half. Shovels sliced into the site where 105 English men and boys planted their settlement in April 1607 and at May’s end began to erect a triangular fort of palisades— tree sections stood on end in holes. It replaced a crescent brushwork, Jamestown’s original, short-lived, and inadequate defense.

In 2010, inside James Fort’s boundaries but outside the Confederate earthworks, Kelso discovered the footprint of a 1608 church, the sanctuary where settler John Rolfe wed Pocahontas. The uppermost five feet of its plot were missing—carted away to build Fort Pocahontas in 1861. According to a contemporary account, as they built the stronghold, the slaves happened upon “curious relics” from the colonial settlement, including an iron elbow-piece, or vambrace, from a seventeenth-century suit of armor. Donated to the Virginia Historical Society in the late nineteenth century, it is displayed at Historic Jamestowne’s Nathalie P. and Alan M. Voorhees Archaearium, an artifact museum opened in 2006.

The vambrace is better preserved than armor more recently excavated in the damp, low-lying island, relics reduced by centuries of soil moisture to gobs of rust. To Kelso, the contrast demonstrates the danger of the situation to the artifacts that remain, and proves intensive Jamestown archaeology should not be delayed. “Burials and iron objects are going to be gone in the next twenty years,” he says, as inhumed items deteriorate.

Since 1994, Kelso and co-workers have recovered 1.4 million artifacts. Fort Pocahontas’s earthen walls have been chockablock with small treasures highlighting everyday life in the 1600s. Among them are a paring knife and Elizabethan coins. “Over the years we have screened every square inch of a huge volume of soil,” team member David Givens says. “All the best stuff was up in the Confederate fort.” Though building Fort Pocahontas damaged the southern portion of James Fort, it helped preserve the northern. The Confederate berms’ heavy soil discouraged casual digging by amateur archaeologists and looters. “I’m absolutely amazed at how much of James Fort is left,” says Al Luckenbach, a Maryland expert on colonial excavations. “There were so many opportunities for later generations to ruin the site.”

A heyday of Fort Pocahontas was the summer of 1861, when the island swarmed with secessionists. Heat, mosquitoes, and waves of illnesses tested their enthusiasm. July 4, Virginia’s John Tyler, former president of the United States, landed at Jamestown wharf to tour and to encourage the rebellion against the Federals. That Independence Day, Tyler gave a speech at the Ambler House that, a soldier said, was aimed at “stirring up hot fighting blood in us all.”

No shot was fired in anger from Fort Pocahontas. Eleven months later, Bluecoats seized the island, destroying what was left of the Confederate encampment and spiking a few remaining cannon. General McClellan informed President Abraham Lincoln of Jamestown’s capture. They ordered the Union navy to steam up the James, and the fleet docked at the island. A sailor from the Monitor, looking out at the seventeenth-century church tower, contrasted “the deep toned piety of the early settlers & the perjured villainy of their degenerate offspring.”

Secretary of State William Seward visited Jamestown—now a staging ground and locus for fleeing slaves—as did McClellan, who wandered among the churchyard tombstones. He found one dated 1698, and plucked flowers to send to his wife.

Lee turned back the Union’s Peninsula Campaign, driving McClellan off to Harrison’s Landing at Malvern Hill on July 1 in the last battle of the Seven Days. Union gunboats, firing from the James, helped stop a Confederate advance and protected McClellan’s withdrawal. The invaders retreated by ship down the James to Fort Monroe from Berkeley Plantation in August. Confederate cannon at Fort Darling, a Confederate stronghold at Drewry’s Bluff just below the capital, had turned back a Union naval thrust against Richmond on May 15. His Virginia scuttled, Lieutenant Catesby ap Jones directed Fort Darling fire at gunboats below, one of them the Monitor. The Union controlled Jamestown Island until war’s end. Its church tower made an observation post.

When General Ulysses S. Grant launched his overland campaign against Richmond in 1864, the Union army established a telegraph station under a white tent in the angle of ruined Fort Pocahontas. From there a wire ran south under the river toward Surry County and west to Grant’s headquarters at City Point—modern Hopewell—near besieged Petersburg. Guerrillas struck now and again. Sabotage of the wire on the Confederate-controlled south bank of the James proved a problem—until it was run along the bottom of the river, twenty-two miles upstream. Allen’s slaves revolted and burned the Ambler House during the war. Rebuilt, it burned again in 1895. Its brick shell stands.

It took Grant until April to drive the Army of Northern Virginia out of Petersburg, and cut Richmond’s last supply line. During the siege, he detailed to Jamestown troops whose enlistments had expired. They guarded the island while awaiting transfer home. Ex-Confederates mustered there after Appomattox to take the oath of allegiance.

Allen, who quit Confederate service in 1862, moved to New York and died at forty-six in 1875, having been forced to sell Jamestown Island. He conveyed his Claremont plantation to Maryland developer Frank Mancha, who in 1879 subdivided it for home sites peddled to Minnesotans and other Northerners looking for warmer climes. It is said that Dixie begins on the south shore of the James. Claremont is a border town. In the central section of the town’s graveyard rises a monument to trans- planted Union veterans.

Fort Pocahontas dominated a stretch of the Jamestown river shore into the twenty-first century, protecting only a monument raised inside in 1907 to the establishment in America of the Church of England three centuries before. The Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin of Williamsburg’s Bruton Parish Church officiated at its dedication.

Among historians it had become an article of faith that the James had long before washed away the ground on which 1607’s James Fort stood. They presumed the site was offshore. Investigators later dredged those waters, finding little.

Kelso, excavating near the church tower, discovered postholes of a palisade. They belonged to James Fort’s inland wall, and they ran in a line to the Civil War bastion. Preservationists debated its partial excavation in the search for more of the 1607 stronghold. Archaeologists have dug up Fort Pocahontas with the same care they apply to James Fort, team member Bly Straube says. “We’ve removed it with shovels and trowels, recording everything using” graphic information system software, “digging in a grid system where it’s all mapped in. We’re not just arbitrarily digging things up.”

Kelso says, “If properly excavated and recorded digitally in 3-D, as we did, it is no longer valid to say we destroy sites.” The National Park Service administers all the island but the fort site and 22.5 surrounding acres. That’s the property of Preservation Virginia, a nonprofit dedicated to perpetuating and revitalizing the state’s cultural, architectural, and historic heritage. Kelso has had a freer hand than excavators on federal property. There archaeology is discouraged except in advance of necessary construction or roadwork. Nevertheless, Kelso says he has met and exceeded federal standards for archaeological site investigation.

Colonial Williamsburg manages the result, a conjunction of an early colonial town and the Civil War. “It’s probably the only place you would have a story like that,” says President Colin Campbell. “I think it’s absolutely fascinating.”

W. Barksdale Maynard contributed to the summer 2013 journal “A New Deal for Old Places,” an article about the Historic American Buildings Survey. His books on American history include Woodrow Wilson: Princeton to the Presidency.

CROPPED.jpg)