Online Extras

Extra Images

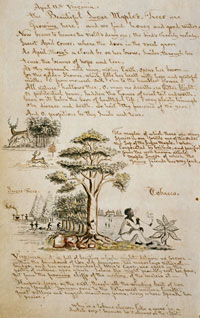

Library of Congress

A branch, leaves, and seeds of one species of maple. The sugar maple produces the most sap for syrup and sugar that could replace cane sugar.

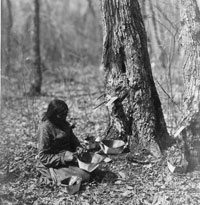

Craig McDougal

“The beautiful Sugar Maples Trees are Growing here,“ the artist-diarist of one April in Virginia wrote; the “Young Friends are very fond“ of the sugar.

Library of Congress

An Ojibwa woman collecting sap in birch baskets. Native Americans had long used sap for sugar and sustenance.

Library of Congress

Workers in a maple syrup camp, around the turn of the twentieth century. Man, beast, and child were involved in the winter work.

Library of Congress

Boiling sap down to syrup requires forty gallons of sap—and a large kettle and much wood—to make one gallon of syrup.

Library of Congress

A girl watches a man pour sap into a tub, around 1900. On the trees, metal spiles—taps—and buckets had replaced wooden ones.

Dave Doody

Tools of the maple syrup trade: an auger to bore a hole in the tree, a mallet to tap the wooden spile in, and buckets to collect the sap.

Thomas Jefferson and the Maple Sugar Scheme

by Mary Miley Theobald

Thomas Jefferson came late to the maple sugar scheme. He was an ocean away in Paris, serving as the United States’ minister to France, when a group of Quakers and Dr. Benjamin Rush collaborated in Philadelphia to promote maple sugar over cane sugar. The advantages of maple sugar were many, Rush wrote, but the clincher was its moral superiority: Cane sugar was grown by slaves, maple sugar by free Americans. His goal was “to lessen or destroy the consumption of West Indian sugar, and thus indirectly to destroy negro slavery.”

Rush and the Quakers were abolitionists. So was Jefferson, in his own fashion. He despised slavery and was eager to promote its demise in the Caribbean, although he could never figure out a way to rid his own country of the “peculiar institution.” Abolitionists had made the connection between maple sugar and slavery before Rush joined the cause, but Rush was its most vocal proponent. Some almanacs pitched in, urging farmers to forsake immoral cane sugar for innocent maple. “Make your own sugar, and send not to the Indies for it. Feast not on the toil, pain and misery of the wretched,” a Farmer’s Almanac of 1803 said.

Jefferson took the cause a patriotic step further. On his return from France in 1789 to serve as the country’s first secretary of state, he joined Rush’s Society for Promoting the Manufacture of Sugar from the Sugar Maple Tree, and proposed a plan. Yeoman farmers of America, he said, could produce enough maple sugar to supply the country’s needs and then some. With little effort, they could export to half the world and put the British sugar producers out of business.

The maple sugar scheme combined Jefferson’s love of botany with his antislavery sentiments, his desire for his country to achieve economic independence, his dislike of the British, and his vision of the yeoman farmer as the backbone of the American republic. “What a blessing,” he wrote a friend in 1790, “to substitute a sugar which requires only the labour of children, for that which it is said renders the slavery of the blacks necessary.”

Turning maple sweet water into solid sugar was not quite the effortless undertaking Jefferson imagined. It took more than farm children to find and tap suitable maple trees, lug heavy buckets of sweet water—or sap—to a sugarhouse, and chop the immense quantities of wood needed to boil the water down to sugar. About forty gallons of sweet water are needed to make one gallon of syrup or five or six pounds of sugar. Nevertheless, in principle, Jefferson was right—maple sugar is easier to make than cane sugar, and it requires little investment in machinery, animals, equipment, or slaves. A typical farmer has all he needs in his shed and kitchen. A farm family could realistically expect to produce 200 pounds of sugar in a season— plenty for themselves with leftovers to sell. Best of all, sugaring is harvested in late winter and early spring, a slow time in the farming cycle, so it interfered with nothing.

Benjamin Rush listened to what he called Jefferson’s “useful hints” and incorporated these into an upbeat how-to pamphlet. The publication, intended to help neophytes start up their own operations, was widely distributed. “It owes its existence to your request,” he wrote to Jefferson.

Rush’s pamphlet touted the superiority of pure maple sugar. It cost half of cane. At harvest time there were no insects about “to feed upon it, or to mix [their] excretions with it,” something certainly not so in the buggy West Indies. Free Americans had cleaner hands than slaves: “Men who work for the exclusive benefit of others are not under the same obligations to keep their persons clean while they are employed in this work, that men and women and children are, who work exclusively for the benefit of themselves, and who have been educated in the habits of cleanliness.” Moreover, who could disagree with America’s best-known doctor when he said that eating maple sugar had nothing to do with rotten teeth and prevented malignant fevers? “The plague has never been known in any country where sugar composes a material part of the diet of the inhabitants,” he said.

While working in Philadelphia, Jefferson developed serious headaches, probably migraines. When his friend James Madison, then Virginia’s representative to Congress, proposed a month-long trip north, Jefferson wrote to President George Washington, “I think to avail myself of the present interval of quiet to get rid of a headache which is very troublesome by giving more exercise to the body and less to the mind.”

Jefferson’s mind never rested. In May of 1791, he and Madison set out on horseback for Vermont, the country’s fourteenth and newest state, with Jefferson’s slave James Heming driving a carriage behind them. During the coming month, they would travel by river and road through upstate New York, Vermont, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Long Island—a journey of more than 900 miles—before heading back to Philadelphia.

Maple sugar manufacture was not Jefferson’s only interest on this trip, but he pursued it vigorously. He missed the sugaring season, which usually begins in February and can go as late as April, but that didn’t discourage him from urging small farmers and large landowners alike to plant orchards of maples as they would apple trees. “I have never seen a reason why every farmer should not have a sugar orchard, as well as an apple orchard,” he wrote. Cane sugar was America’s largest import—the oil of its day. A new cash crop would cut into the trade imbalance.

Many Vermonters got the message, and at least one large-scale sugaring operation was launched. Following his own advice, Jefferson bought sixty maple saplings in New York to start an orchard on the slopes of Monticello.

Early French fur traders learned about maple sugar from the Indians. Peter Kalm, a Swedish botanist who wrote about his experiences with the northern tribes, said in a 1751 report, “The savages from prehistoric times, long before the Europeans discovered America, made maple sugar. The Europeans have now learned the method and nearly all of them who live where this tree grows make a large quantity of sugar each year.”

The Indians probably learned the secret from nature. Timothy D. Perkins, professor and director of the University of Vermont’s Proctor Maple Research Center, writes,

It is likely that the native peoples of North America observed squirrels and birds creating wounds in sugar maple trees in the early spring, figured out what they were doing (eating the sugar crystals that formed through evaporation of the water), and mimicked them to make maple sugar. They may have also discovered that broken branches of maple trees exuded sweet sap, sometimes forming sweet icicles.

Those icicles sometimes are called sapsicles.

The process fascinated Europeans. Dozens of accounts written by missionaries, Indian captives, and fur traders as early as the 1550s described the technique. A couple of tomahawk chops across the bark and a birch-bark basket to catch the sap started the process. Indians boiled their meat in the sweet water, they poured the syrup over snow, and they mixed sugar with corn meal, chestnuts, and berries to make what sounds like a granola bar. Sometimes they lived on sugar. For a month or more in late winter, it became their principal food.

Some Indians used wooden molds to make decorative shapes of sugar. Johann Georg Kohl, a German who lived among the Ojibwa near Lake Superior, wrote in 1859 that “they pour it, just before crystallization, into wooden moulds, in which it becomes nearly hard as stone. They make it into all sorts of shapes, bear’s paws, flowers, stars, small animals, and other figures, just like our gingerbread-bakers at fairs. This sort is principally employed in making presents.” A hundred years earlier, Peter Kalm had written, “If sugar in a special form is desired the thick syrup can be . . . poured into shells or other vessels, depending on the shape desired, and allowed to cool.”

Virginians did not discover the miracle of the sugar maple until the end of the seventeenth century. Robert Beverley’s History and Present State of Virginia, published in 1705, says, “Though this Discovery has not been made by the English above Twelve or Fourteen Years; yet it has been known among the Indians, longer than any now living can remember.” Beverley compares maple sugar to coarse cane sugar in taste and appearance. “It was bright and moist, with a large full Grain; the Sweetness of it being like that of good Muscovada”—an unrefined brown sugar with a molasses flavor. Native Americans told Kohl that maple sugar “tastes more fragrant—more of the forest.”

Indians tapped other trees too, although none were as bountiful as the maple. Kalm mentions sugar birch and hickory, but says that these trees produced “such small quantities of sap that it is not worth the trouble.” Birch sap is not as sweet as maple, and it takes more than twice as much to make syrup—usually one hundred gallons of birch sap to make one gallon of syrup. The owners of today’s Kahiltna Birchworks in Alaska, Dulce and Michael East, reported, “Our 2010 ratio was low—only 114:1!” Birch syrup has a distinctive, bitter bite, with a coffee-like flavor.

Europeans improved on Indian practices by substituting copper or iron kettles for birch bark and wood. Later, tin buckets replaced traditional wooden troughs. Using augers to bore a small hole damaged the trees less than ax chops, letting them be tapped year after year with no ill effects. In the twentieth century, the spout and bucket gave way to a system of slender plastic tubes running to a central collection point or directly into the boiling room.

America’s maple sugaring was not limited to New England and the upper Midwest. During the eighteenth century, Englishmen as far south as the Carolinas observed Indians tapping “the Sugar-Tree,” which “is found very plentifully towards the Heads of some of our Rivers” in the cooler, mountainous regions of North Carolina and Virginia. Maple trees flourish beyond those regions, of course, but they are not necessarily sugar maples, acer saccharum. Without warm days and frosty nights, the production of sweet water is insufficient to make syrup or sugar.

Today’s scientists say that the ideal is a fluctuation between twenty degrees at night and forty during the day. This temperature swing is what makes North American maples produce so much sweet water, and it explains why Europeans, who grew up with maple trees in parts of northern Europe, never discovered how to tap theirs. Where maples grow in Europe, temperatures do not fluctuate sufficiently to produce the flow.

Jefferson’s hopes for sugar independence came to naught; however they led to an increase in maple sugar production in the North. His own sugar maples, like his vineyards, did not thrive at Monticello. There would be neither wine nor maple sugar made on commercial scales in Virginia for decades. Of the sixty saplings planted at Monticello, all died within a few years. Twice more he sent for trees, but results were similar. Not until the twentieth century was Jefferson vindicated, as Virginians found success in wine and maple syrup. Though grapes can grow in most parts of Virginia, maple sugaring is limited to the mountainous, western edge of the state.

Highland County is one of Virginia’s smallest counties as measured by population, with a few more than 2,000 inhabitants. Each year the number swells as more than 70,000 people from all over the mid-Atlantic region flock to the Maple Sugar Festival. Started in 1958, the festival is traditionally on the second and third weekends in March, although sugaring goes on for as long as six weeks. Visitors can stop by a dozen sugar camps to watch modern or traditional preparation and, of course, to buy jugs of syrup and packets of sugar candy. The whole county celebrates the bounty of the sugar maple tree. Everyone over the age of five pitches in to cook and serve the fire department’s all-you-can-eat pancakes, the Ruritan’s hot maple donuts, the Methodist Church’s maple funnel cakes, and the Presbyterian’s maple barbeque chicken.

Nearly all maple sap is made into syrup today. Before the Civil War, sugar was the dominant product. When maple sugar was half the price of imported cane sugar, it was America’s commonest sweetener. As the price of cane sugar fell and beet sugar entered the picture, maple sugar makers switched to syrup.

The bottle of pure maple syrup on the top shelf at your grocery store? That likely came from Vermont, Maine, or upstate New York, thanks, in part, to Jefferson’s scheme.