They Did the Best They Could

by Gil Klein

Dave Doody

Colonial Williamsburg's Carl Lounsbury says architectural researchers today have advantages not available to their predecessors — technology and time.

Colonial Williamsburg

With plans in hand, (left to right) W.A.R Goodwin, engineer Robert Trimble, John D. Rockefeller Jr., and Arthur Shurcliff, the Foundation's first landscape architect, confer on the lawn of the George Wythe House.

Colonial Williamsburg

Excavation of the Governor's Palace's basement and foundation took place in 1928.

Colonial Williamsburg

The Capitol's distinctive twin apses are features from the original building rather than the second.

Colonial Williamsburg

This 1941 photo shows the Raleigh Tavern, which was rebuilt as part of the restoration of Colonial Williamsburg.

Colonial Williamsburg

Water pumps, like this one at the Morton House, would not have been part of an 18th-century decorative garden.

Walk down Duke of Gloucester today and you are enveloped in a vision of the 18th century — fifes tootling and drums pump-a-rumming, an occasional roar of a cannon, the clip-clop of horse's hooves and shouts of re-enactors portraying scenes from 1776, squeals of modern children caught up in the pageantry of the past.

And most importantly, you see the buildings that have come to embody to people around the world what Virginia's colonial capital — and all of colonial America — looked like at the time of the American Revolution. Many of the shops and houses are brightly painted in multiple hues. At the end of the street stands the Capitol that you walk around to reach the main entrance.

But is this what Thomas Jefferson would have seen when he walked down Duke of Gloucester Street in 1776?

Carl Lounsbury knows from 30 years of careful study that the historic area buildings are not precisely as they were in colonial times. When he walks down Duke of Gloucester Street, he sees what's around him, but he also sees the town as it probably appeared in 1776.

The color scheme is all wrong on that house. That chimney is on the wrong side of that shop. These fences aren't at all right; they would have let in the pigs. Front porches are missing from the taverns. There are too many bay windows and too many formal gardens.

All these trees? Probably weren't here, even though the visitors welcome their shade. This one-story building should have been two stories. One of the most impressive mansions is gone.

“We see things that look good. We see other things that makes us think, just how in the world did they come up with that? We see other elements we sort of understand and some things that they just missed the boat and didn't quite understand what was going on,” he said.

“They” are the architects who put together the Colonial City from 1927 to 1934 to fulfill the dream of W.A.R. Goodwin and John D. Rockefeller Jr.

Lounsbury isn't being critical. In fact, he's in awe. What those architects accomplished in seven years — with the tools and knowledge they had — is nothing short of remarkable.

“Think about it,” he said in his office just outside the Revolutionary City. “The Raleigh Tavern, the Capitol and the Governor's Palace were all below ground and had to be reconstructed in three years. At the same time, they were rebuilding the college building and several other buildings. That's incredible.”

They did not have the luxury of time that Lounsbury and his colleagues enjoy.

He said he took three years to research courtroom interiors before restoring the courthouse in 1991. The original architects might have had three months to gather up as much information as they could about the inside of that building.

You must get into the minds of the original architects to understand why Williamsburg's Historic Area looks the way it does. By the late 1920s, Colonial Revival architecture was flourishing as Victorian styles faded.

Architects seeking to become part of the Colonial Revival trend scoured the country looking for 18th-century buildings and carefully recording the architectural features that made them distinctive. They faithfully included these into new construction. Copies of colonial-style buildings sprouted all over the country.

Historic preservation began with saving George Washington's Mount Vernon in 1858 and had been building through the last part of the 19th century. But no one had attempted to revive an entire town. Rockefeller agreed to finance the project only if it included the town's entire historical area.

To plan the work, the Foundation hired the Boston architectural firm of Perry, Shaw and Hepburn, who were enthusiastic students of Colonial Revival architecture. They were exquisite draftsmen who had compiled detailed drawings from many colonial-era buildings.

“They recorded mantels, stairs, cornices, doors and other features from the best gentry houses in Virginia, which they integrated directly into many of their designs for the reconstructed buildings of the historic area,” Lounsbury said.

“Cribbing elements from the field, they followed the common practice to give their new work a period of authenticity.”

That's how a distinctive chimney that looks exactly like the ones on Stratford Hall, the birthplace of Robert E. Lee nearly 100 miles away, ended up on a building on Duke of Gloucester Street. The original architects sought out old photographs, insurance plats and undertook rudimentary forms of archaeology to try to determine what had been there.

“They would dig until they hit a wall, and then root around it like a rodent and expose the foundations,” he said. “That was what they were interested in, little knowing that they could learn a whole lot more by sifting through the sand and soil and picking up details that we spend a lot of time doing today.”

So they might have the foundation and an 1810 insurance plat that said it was a two-story building, he said. They might have found an old photograph from the 1870s of a family, and to one side you could see a building and notice that it had a dormer here and a door there. They even talked to people who had been children in the 1850s and 1860s who could say a wooden house had once been there.

They may have gotten the architectural details right, but they had only an imperfect understanding of how these details fit together in a system of design, he said. They didn't know how architectural details were used to express how a building functioned.

In contrast, the people who have been working in the architectural research department for the past 30 years consider themselves building historians. They have studied how these buildings worked.

“Many of us are social historians interested in the dynamics of colonial society,” he said. “While we seek precedents on which to base our designs, we do not slavishly copy detail from the best houses. We seek to understand the hierarchy of ornamentation that would be appropriate for each site, building and room.”

The key, he said, is understanding who was using the building and for what it was used. The details of the architecture must fit the function of the building and its relative importance in colonial life.

That's how he could know, as he walked down Duke of Gloucester Street, that a chimney was constructed on the wrong side of a shop. To the untrained eye, the shop looks like it fit right into the 18th century. But Lounsbury knows that the showroom side of a shop at that time was unheated while the office side was heated. This building has the fireplace in the showroom.

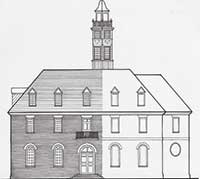

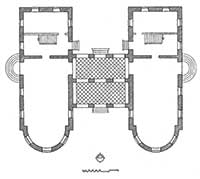

Perhaps the most curious story is how the Capitol ended up looking as it does. It is the most important building in Colonial Williamsburg where representative government was developed and major events leading to the Revolution were played out.

Its two wings with their apses are the iconic vision of Colonial Williamsburg.

But this version of the Capitol is fundamentally flawed, Lounsbury said.

The original Capitol, built between 1701 and 1705, burned in 1747, and was rebuilt four years later in the same place, but not exactly in the same way. The second Capitol also burned in 1832.

Given that Colonial Williamsburg was built to portray the city as it stood just before the Revolution, one would assume that the architects would choose the design of the second Capitol, Lounsbury said, and that was their plan.

But they realized they did not have enough documentation on the design of the second Capitol, so they built the first one — with the distinctive twin apses — for which they had much better documentation instead of the second Capitol that had squared off the apses.

More importantly, the main entrance to the Capitol was never on the side between the two wings where it is now. In the years leading up to the Revolution, that was an enclosed hallway that held Lord Botetourt's statue.

In colonial times, the main entrance was always at the end of Duke of Gloucester Street, where one would assume the front entrance would be since it faced the town's main street.

And the doorway constructed on this west façade in the 1930s is not where it was in either of the two prior Capitols.

If you stand in the middle of the Duke of Gloucester Street and look at the Capitol, you can see where the main entrance would have been — about six feet to the right of where the door is now.

The 1932 architects just could not believe that the west facade of the first Capitol was asymmetrical. They insisted that there had to be two windows to the right of the door and two to the left. The doorway they constructed was fairly plain because they didn't think it was the main entrance. They ignored the evidence of a semi-circular portico and moved the main entrance around to the side of the building where it remains today enshrined in the Colonial Williamsburg logo.

Actually, the main entrance had both a semi-circular portico and a balcony above it. The door lined up nicely under the tower and with the center of Duke of Gloucester Street.

“They didn't even understand where the front of the building was,” Lounsbury said. “They simply had not studied traditional Virginia courthouses of the late 17th century of which the Capitol is an oversized version.”

What's not in Colonial Williamsburg can be as important as what is there. When reconstruction began, Tazewell Hall was among the most prominent houses dating back to the colonial era. But it was dismantled and parts of it were reconstructed in nearby Newport News.

Two things were going against saving it, Lounsbury said. First it was near where the Williamsburg Inn and Lodge were set to be built. And second, at the time of the Revolution, it was owned by Sir John Randolph, who was the colony's attorney general and who fled to England when hostilities began. His story did not fit into the narrative of patriots that John D. Rockefeller Jr. envisioned.

“So being in the wrong place and having a dangerous history combined to seal its fate,” he said. “It's one of the greatest blunders we made here to have it taken down and sold off.”

To be authentic to the 18th century, many of the city's taverns should have front porches, he said, but none constructed during the 1930s does. Certainly the Raleigh tavern, the city's most important one, had a front porch.

When the Charlton's Coffeehouse was reconstructed next to the Capitol in 2008, he said, his office had the time to do the research and to use new dating techniques on the wood from the remaining foundation so it could be rebuilt exactly as it was — with a front porch.

Lounsbury stopped next to the Brickhouse Tavern. Not only is it missing the front porch, he said, but it should have been a full two stories tall, something that would have given Duke of Gloucester Street a more urban appearance.

“It's strange why they decided to build it one story,” he said. “There was good evidence — several insurance plats — that said it was two stories.”

One of the things that makes Colonial Williamsburg so attractive are the low, open fences that allow people to look into formal gardens on

the side or behind houses, he said. But in colonial times, those fences would have been high to keep out pigs and other animals that scavenged the streets. And there would have been far fewer formal gardens in 1776.

Especially puzzling to a colonial person would be the water pump that is the centerpiece of the garden at the Morton House. No 18th century person would have put something as utilitarian as a water pump in the middle of a decorative garden. And the paint colors? Colonial Williamsburg colors are famous nationwide and sold in hardware stores everywhere. People love to duplicate the paint schemes that often have four, five or more colors — walls of one color are offset by trim in another color and doors in yet another color, sometimes even two.

But new techniques in paint analysis show that the colors were different; the houses certainly were not multi-colored and outbuildings were not painted at all. They were tarred or whitewashed.

“What we discovered from documents and paint analysis is that most buildings were painted one color on the outside, perhaps with a contrasting color on the front door,” he said.

“This is purely a colonial revival approach to things,” he said of the multi-colored houses and outbuildings. “It's easy for us to paint over the buildings, but it does tone down the Colonial Revival aesthetic.”

So, should everything be changed to reflect what modern research has found — tear down the Capitol and start again? Absolutely not, Lounsbury said.

For one thing, the Capitol as it is constitutes a historic building. At more than 80 years, it has lasted longer than either of its two predecessors. Like many aspects of the city, the Capitol is a fine example of Colonial Revival architecture as it was conceived in the late 1920s and early 1930s, and must be preserved as such.

For another, the next generation of architectural historians with even greater technology and insight might decide that he and his comrades made their own mistakes. The job of the present generation, he said, is to make sure that new restoration work is as accurate to the 18th century as their knowledge allows.

And if Thomas Jefferson were to come back to life and walked down Duke of Gloucester Street, he would feel at home, Lounsbury said.

“He would recognize the exterior of the palace, but some of the interior details would confuse him. They are based on details in aristocratic English houses, which would have been far too expensive for the palace's builders at the beginning of the 18th century.”

While Jefferson would recognize the town, he said, something about it would seem stilted and odd.

“It's like someone trying to create an elephant without ever seeing one,” he said, “but getting a box of parts and putting them together in a way that's close but doesn't quite fit the way it should.”