Online Extras

Political Cartoons by William Hogarth

Yale Center for British Art

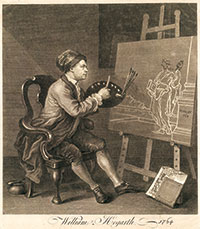

The painter’s self-portrait. Hogarth moved from the oils and easel of fine art to a lucrative world of satirical prints.

Colonial Williamsburg

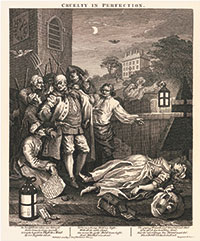

In “Credulity, Superstition, and Fanaticism,” he defrocks Methodist enthusiasm, an unholy mix of spiritual and sexual excess: the harlequin minister at top sermonizes “I speak as a fool,” a minister thrusts an icon down the dress of a girl in ecstasy, a woman gives birth to rabbits, but a spiritual thermometer, in the right corner, registers the fervor as only lukewarm.

Wikimedia

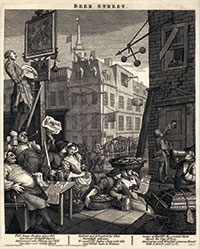

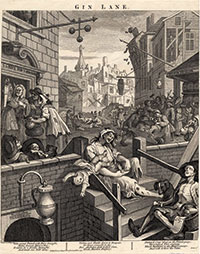

“Gin Lane,” above, batters the viewer with the wreckage of booze-soaked inhabitants and the horrors of London life. It led to legislative reform that reduced consumption of gin. Opposite, ‘Beer Street” championed the virtues of moderation in alcohol and the resulting benefits for public morals.

Yale Center for British Art

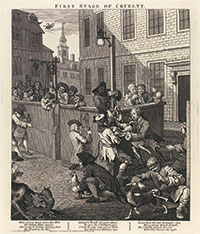

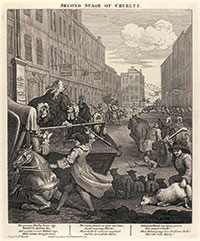

Hogarth’s progresses, panels of narrative images, were a precursor to the political comic strip. The heavily freighted moral tales warned of the corruptions of modern life.

Bridgeman Art Library

Hogarth’s “Humours of an Election” series, here in his original oils before they were engraved for black-and-white prints.

Ingenious and Inimitable, Artist William Hogarth Chided Authority, Ridiculed Pomposity, Mocked Religion, Pointed Out Misbehavior, and Invented the Satirical Comic Strip

by James Breig

For the past half-century, more and less, Pat Oliphant and Garry Trudeau have been among the leading American newspaper cartoonists lampooning political figures, making cogent points about social issues, and caricaturing their countrymen. That satirical squint also can be found in drawings in national magazines, on websites, and on such animated television series as The Simpsons. They’re in a tradition at least as old as the eighteenth century’s William Hogarth.

An advertisement of goods for sale published by Williamsburg’s Virginia Gazette on September 17, 1771, listed “some election pieces by Hogarth.” Seven years later, a notice offered the contents of a house halfway between Yorktown and Williamsburg, valuables including “a dozen of mahogany chairs . . . two feather beds . . . several sets of Hogarth’s prints in frames.” Hogarth had died in 1764, but his popularity persisted. One magazine’s notice of his death defined him as “the celebrated comic painter.” In 1804, London’s Gentleman’s Magazine called him “the ingenious and inimitable artist.” An 1879 assessment of his work said he was “a writer of comedy with a pencil.” His influence can be detected in cartoonist Thomas Nast’s satires of political corruption in 1860s New York City, as well as in the “Doonesbury” comic strip Trudeau began in 1970.

Hogarth was in the first place a serious painter, as evidenced by a self-portrait and a collage of his six servants. He painted biblical scenes and wrote The Analysis of Beauty, in which he set out “to show what the principles are in nature by which we . . . call the forms of some bodies beautiful.” Yet he is most often associated with pictorial satire. The son of a ne’er-do-well father whose family was confined with its breadwinner in debtor’s prison, Hogarth invented comic strips with serious points to make, and acerbic political cartoons. He deployed his artistic skills to chide authority, ridicule pomposity, mock religion, and point out misbehavior at all levels of English society.

Sean Shesgreen, editor of Engravings by Hogarth, says the artist “was interested in promoting middle-class morality. He was a reformer, whether in ethics, aesthetics, politics or painting.” His impact on his times was so strong that this phase of the eighteenth century in England is called Hogarthian. Catherine Zinser, who curated a Hogarth exhibition at the Blanton Museum of Art in Austin, Texas, said, “Hogarth sought to ignite social change though his artwork. He publicized the financial downfall and corruption of his contemporaries—something he saw firsthand with a father in and out of debtor’s prison.” Young Hogarth engineered his route to respectability by deploying his artistic talents, beginning as an apprentice silver engraver and rising to become Serjeant Painter to the King. In between, he practiced an early form of satirical comic strips that he called “progresses,” multiple-panel prints on what he said were “modern moral subjects.”

In those works, Zinser said, Hogarth “contrasted virtue and vice; one avenue led the viewer to honor and riches, while the other led to dreadful consequences and disgrace.” To reach a wide audience, he chose the vehicle of engravings for prints because of their “quick turnaround,” she said. “He even printed on different grades of paper to sell at lower prices.” Much like contemporary cartoonists, who franchise their characters and proffer their works on multiple platforms, Hogarth found that success lay in providing people with his work at reasonable prices.

According to the Tate Museum in London, “The richness and inventiveness of Hogarth’s narratives was accompanied by a remarkable form of artistic entrepreneurialism. He took on the jobs of advertising, engraving and selling print versions of his paintings, thus establishing himself as an independent artist rather than a print-publisher’s hack. . . . Hogarth lobbied in Parliament for greater legal control over the reproduction of his and other artists’ work. The result was the Engravers’ Copyright Act (known as ‘Hogarth’s Act’), which became law” in 1735. It was the first instance of copyright protection being extended beyond written materials.

Hogarth had the ability to simultaneously amuse, shock, and change society. “Gin Lane,” his portrayal of the horrors wrought by alcohol addiction, demonstrates it. The print was paired with “Beer Street,” which taught that moderation led to happiness. He said that “Gin Lane” illustrated every circumstance of gin’s “horrid effects. . . . Idleness, poverty, misery, and distress, which drives even to madness and death, are the only objects to be seen.” Half-a-century later, British essayist Charles Lamb said of Hogarth’s images, “Other pictures we look at—his prints we read.” Ronald Paulson, who has written books about Hogarth, said that his prints “were not merely illustrative, but verbal, ironic, iconic and emblematic.”

The punch of "Gin Lane" was as powerful as any of the twentieth-century’s editorial cartoons that prodded social change, sliced at presidents, or protested war, drawn by the likes of Pulitzer Prize–winners Oliphant and Herblock—Herbert Block. It led to Parliament’s passing a 1751 act that lowered alcohol consumption by increasing the cost of gin’s manufacture. Martin Rowson, a British cartoonist and satirist, says it remains “always an easy quotation for cartoonists to employ to make a point about drunkenness, despair, inner-city decay.” University of Kentucky history professor Mark Wahlgren Summers said Hogarth’s career pivoted with “Gin Lane” and sees no equivalent in art to that time. The cartoon, he said, with “its mobs in the street and drunken mothers dropping babies over the sides of staircases” inspired later artists. The nineteenth-century English caricaturist James Gillray, as well as Nast, for instance, used gruesome detail Hogarth-style to shock viewers literate and not into action.

"Many another cartoonist is heir to the Hogarth tradition of indignation at wrong,” Summers says, “and an awareness that the wrong went much deeper than the powers-that-be at the top of politics. Thanks to Hogarth,” his satirical heirs “believe that humankind, in all its foibles and frailties, is fair game. Thanks to him, they believe that an artist’s job is to get mad—and, while maybe making people laugh, getting them mad, too.” Oliphant, an Australian who made his mark in the United States, told an interviewer that is what keeps him going in his mid-seventies: “I just get mad. I get pissed off at certain things, and certain things need to be said. So I just go ahead and do it.”

Summers says Hogarth’s “sense of moral outrage at the state of society” was “something that had not found any real outlet in English cartoon art before that time.” The closest comparison he could name was Alexander Pope’s poetry. Summers says that “the anger and sense of social injustice that Pope put into his poetry—think of ‘The Dunciad’ or the bitter asides in ‘Rape of the Lock’—Hogarth expressed with his engravings. His pictures were more than a meal. They were a feast. You can look at his pictures about the times of day and find a thousand things going on.” Hogarth’s progresses present changes in his characters: in the six-panel “Marriage à-la-Mode,” a devolving marriage; in the eight-section “Rake’s Progress,” the slow corruption of a young man; in the six-scene “Harlot’s Progress,” a young woman’s.

Hogarth’s influence on modern satirists, including Trudeau, is seen in this elongation of stories. “Hogarth’s tales are shorter—two to twelve scenes—but they do belong in the same family of artists,” Shesgreen says. Fiona Halloran, author of Thomas Nast: The Father of Modern Political Cartoons, said, “All editorial or political cartoonists are quick to perceive hypocrisy, and enjoy revealing and mocking it. They tend to believe passionately in some things and to use their art to advance those causes.”

Hogarth’s cartooning ranged from grand ideas, such as his four-panel “Election” series, mentioned in the 1771 Gazette ad, to jibes that seemed ephemeral at first but contain deeper meaning—and perhaps invented a medium. Michael Dean, author of I, Hogarth: A Novel, said that “arguably, the truest ‘satire’ Hogarth ever drew was at the instigation of Mary Edwards, when she asked him to mock the fashions of the day in revenge for having her own dress sense criticized. The resultant drawing, ‘Taste in the High Life,’ is a satire because it contains a high degree of deliberate distortion.” That distortion, he said, makes it “a cartoon in the modern sense of the word.”

David Low, a twentieth-century British cartoonist whose targets included Hitler and Stalin, said Hogarth was “the grandfather of the political cartoon,” which Rowson seconds. The family line is easy to trace: Hogarth to Thomas Rowlandson and James Gillray . . . from them to George Cruikshank—called, with Hogarth, “the Alpha and Omega of English pictorial satirists”—and John Tenniel . . . from them to Thomas Nast in America and the scores of twentieth- and twenty-first-century cartoonists who jabbed at the powers-that-be as daily newspapers boomed. Sara Duke, a graphics curator at the Library of Congress, said Hogarth might outrank his successors, because “I’m not sure many modern cartoonists can trust their audience to make the leaps that Hogarth took for granted.”

Rowson said that Hogarth “established a journalistic tradition that’s still flourishing today.” He was “a moralizing satirist” who “refined a pre-existing tradition of visual satire, taking it to previously unscaled heights of sophistication and skill. Through the popularity of his output, he placed visual satire shoulder-to-shoulder with the textual satire of the times. Swift wrote a poem to the young Hogarth, praising him and proposing that they collaborate.” In it, Swift said,

Were but you and I acquainted

Every monster should be painted."

Actor David Garrick wrote an epitaph upon Hogarth’s passing that said in part:

Farewell, great painter of mankind,

Who reach’d the noblest point of art;

Whose pictur’d morals charm the mind,

And thro’ the eye correct the heart!

James Breig contributed an article on eighteenth-century science fiction to the autumn 2013 journal. He writes from near Albany, New York.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Michael Dean, I, Hogarth: A Novel (London, 2012).

- Bernadette Fort and Angela Rosenthal, eds., The Other Hogarth: Aesthetics of Difference (Princeton, NJ, 2001).

- Mark Hallett, The Spectacle of Difference: Graphic Satire in the Age of Hogarth (New Haven, CT, 1999).

- Cindy McCreery, The Satirical Gaze: Prints of Women in Late Eighteenth-Century England (New York, 2004).

- Ronald Paulson, Hogarth: High Art and Low, 1732–1750 (New Brunswick, NJ, 1992).

- Helen Pierce, Unseemly Pictures: Graphic Satire and Politics in Early Modern England (New Haven, CT, 2008).

- Sean Shesgreen, ed., Engravings by Hogarth (New York, 1973).

Cartoonist Martin Rowson’s video about William Hogarth can be seen here: tate.org.uk/context-comment/video/cartoonist-martin-rowson-talks-about-hogarthslondon