Online Extras

-

Extra Images

Janus Images

From an 1853 Harper’s Monthly story on Monticello can be seen views of the house, below, and the Shadwell mills, both central to Jefferson’s attempts to extract himself from the thickets of debt ensnaring him in old age. He died before either was sold.

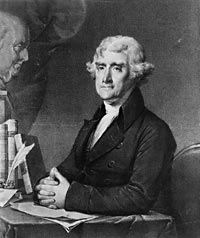

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation

Citing his service to Virginia and the nation, Jefferson applied to the state legislature to grant him a lottery to pay off his debts. They agreed, tickets were issued, but the lottery was never conducted.

The Thomas Jefferson Foundation

Jefferson’s daughter Martha Randolph prudently thought the Shadwell mills—the site and ruins, above—would generate better income than Monticello and that her father should sell the house and farm. Jefferson “turned white” at the thought of losing them.

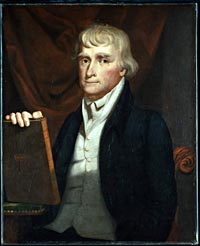

The monument above Jefferson’s grave at Monticello had to be replaced, because souvenir hunters chipped away at the first one.

The home that Jefferson designed, built, and lived in at Monticello was sold after his death to satisfy some of his debts.

Monticello Was among the Prizes in a Lottery for a Ruined Jefferson’s Relief

by Gaye WilsonThomas Jefferson was not sleeping well. The former president, now almost eighty-three years old, was tormented by worries: his debts were increasing, he could lose all he had, including his home, Monticello, and his family could be left destitute. Jefferson had lived with debt most of his adult life, but the amounts now owed and the interest due were growing beyond any pretense that his estate could cover them. Then one night, late in January 1826, an idea came to him. The next morning he summoned his eldest grandson, Jefferson Randolph, and outlined a plan for a lottery to fund the liabilities.

The depressed Virginia real estate prices of those days made the idea of a lottery attractive. Jefferson calculated that if he were allowed to conduct a lottery rather than attempt an outright sale, his mills on the Rivanna River would cover his debts and leave Monticello and the Monticello farm for him and his family. There was one significant hurdle. Lotteries were carefully regulated in Virginia and could be staged only with the state legislature’s approval.

Jefferson set to work immediately on a petition for his grandson to hand carry to the capital in Richmond. His document reviewed the history and use of lotteries in Virginia, and put forward his case. He approached first the question of morality that might be attached to any game of chance and argued that almost every human endeavor involved some degree of chance, especially farming. Could this be viewed as immoral? He listed lotteries that had been run in Virginia since the Revolution and included the financial objective of each, usually public works. His application had a more personal purpose—payment of his own debts. He made no attempt to minimize this issue but built his case with a summary of his more than sixty years of state and national public service, concluding with his most recent endeavor, founding the University of Virginia. Those past sixty years had been an extraordinary time, decades of events that certainly would not be duplicated, and so he proposed that his circumstances and his petition were singular.

The use of lotteries to satisfy private debts was familiar to Virginia planters of Jefferson’s generation. Before the Revolution, advertisements appeared frequently in the Virginia Gazette promoting “A Scheme for disposing of, by way of lottery, several valuable tracts of land,” and the like. Jefferson got firsthand experience when he helped manage a lottery for his cousin, George Jefferson, in 1768.

Debt had become a way of life in the colony because British merchants were willing to extend long-term credit for consignments of produce, usually tobacco. With this credit, the planters could indulge in the growing commercial market stemming from London. If a crop failed, sale of land or slaves was the fallback for revenue when no more credit could be had. But as debt increased, and because there was little specie circulating in the colony, selling large tracts of land grew difficult. Smaller parcels offered through a drawing of lottery tickets purchased for as little as £5 to £10 each stood to attract wider participation.

Like so many planters, Jefferson grappled with debt all his adult life. His patrimony from his father, Peter Jefferson, had very little debt attached and was essentially solvent, but the son acquired substantial debt with his wife’s inheritance. Martha Wayles Jefferson was entitled to one-third of her father John Wayles’s estate, which was sizable but heavily encumbered with debts to British creditors. In such situations the debts could be avoided if the estate remained untouched until creditors were paid, but if the assets were distributed, the debts moved with them.

In 1774, as Jefferson and his brothers-in-law Francis Eppes and Henry Skipwith studied the estate, they were confident that sales of the less-desirable lands could liquidate the British debts. The plan was sound in 1774, but then came the Revolution. Jefferson proceeded with his portion of land sales as planned and accepted the purchasers’ bonds with the pledge to pay in installments, as was customary. But the payments were made in the depreciated paper money issued during the war. Under Virginia’s wartime legal tender act, Jefferson was obligated to accept the money, which he would later describe as not worth “oak leaves.” The Treaty of Paris of 1783 worked against the Wayles heirs because it provided that creditors on either side were due payment in sterling. In Jefferson’s words, “The paper-money for which my lands were sold with a view to pay off Mr. Wayles’ debts, leave this work to be done over again.”

Yet getting to this “work” of liquidating personal debts never seemed to fully capture his attention. He was far more intellectually and emotionally engaged in the challenges of shaping a new nation. In the years that he was minister to France, secretary of state, vice president, and president, he expected that the salaries he drew would cover his living expenses and so leave the profits from his farms to be applied toward his debts. That never seemed to work as he had planned. Jefferson was perplexed by a report he received while in Paris from his neighbor and business supervisor, Nicholas Lewis. With the amount received for the crop, after deducting that due the overseer and steward, paying transportation, clothing for the slaves, tools, medicine, and taxes, the profits were negligible. Did he need a better overseer? Should he hire out the entire plantation if he could find a responsible person? In the years he was absent from Monticello and into his retirement, he consistently projected higher levels of profit from his estate than were realized.

During Jefferson’s two terms as president, the office provided an attractive annual salary of $25,000. From this sum, however, he had to pay the staff for the President’s House and his own secretary, as well as cover travel, entertainment, and miscellaneous expenses. The fine food and wine served at the president’s small dinner parties became legend, but stocking larder and cellar was costly. As he prepared to leave office, Jefferson was shocked to learn that by trusting “rough estimates in my head,” he had exceeded his salary by three to four months, which meant he had a debt of about $10,000 that had to be covered. A loan was arranged, and though he had written to his daughter Martha of the “gloomy prospect of retiring from office loaded with serious debts,” he maintained in his characteristic optimism: “I nourish the hope of getting along.”

His finances worsened in retirement. The War of 1812 disrupted commerce. With peace came a brief period of inflated agricultural prices, but that economic bubble burst. As prices fell, the Second Bank of the United States began to tighten credit, creating the Panic of 1819. Before the recession was fully felt, Jefferson had entered a spiral of taking on new debt to pay the interest on old debts. If he had been willing to sell a substantial portion of his land holdings before the prices began to drop and had applied the proceeds toward his major debts, his financial situation might not have become so critical. Instead, he held on to his estate, always believing that it would cover what he owed. But a recession can be hard to predict, and this one lasted for the rest of Jefferson’s life.

What Jefferson termed his coup de grace was delivered on a loan he cosigned for longtime friend Wilson Cary Nicholas. The amount was large, two notes at $10,000 each, but Jefferson felt obligated. As president of the United States bank in Richmond, Nicholas had arranged and endorsed notes for Jefferson, and he was connected to the family as the father-in-law of grandson Jeff Randolph. Nichols died in October 1820, and his estate, valued at $350,000 when Jefferson had signed his notes in 1818, was now greatly depreciated as well as heavily mortgaged. Jefferson had to add the $20,000 note with $1,200 yearly interest to his own sizable debt.

A severe devaluation of Virginia land prices had troubled Jefferson even before Nicholas’s death, when he had tried his usual fallback of a sale of a small parcel of land to cover an interest payment. In a letter to trusted friend James Madison he laid bare his financial problems and theorized that the current economic situation in Virginia had “peopled the Western States, by silently breaking up those on the Atlantic, and glutted the land market, while it drew off its bidders.”

Did he realize that one of the most significant accomplishments of his presidency, the Louisiana Purchase, had accelerated the depreciation of land in Virginia? It was not so much the addition of territory beyond the Mississippi River as the acquisition of the port of New Orleans that had been Jefferson’s main objective. United States control of the port city guaranteed that American commerce produced in the trans-Appalachian regions would have an outlet to world markets. This made a move west potentially more profitable, and the fatigued land of Virginia less attractive.

Jefferson’s financial situation became public with his lottery petition, presented to the Virginia legislature February 8, 1826. Expressions of dismay immediately reverberated on personal levels and in the press. The Baltimore Patriot said it was appalling that the author of the Declaration of Independence should be on the verge of bankruptcy in his advanced years. Similar sentiments were published in the Richmond Enquirer, especially after some legislative opposition appeared against the lottery scheme. Some objected from old political biases, some on moral grounds, and some closer to Jefferson thought it might tarnish his legacy. On a second vote February 20, however, the lottery passed by a substantial majority.

The lottery bill said that only a fair evaluation at the current land prices could be attached to the properties that were to be offered. Soon it became clear that Jefferson’s initial calculation that his mills and their surrounding property would raise enough to cover his debts was far off the mark. Family correspondence reported that he “turned white” when he learned that Monticello and the adjourning farms would have to be included. Over and over he had expressed hope that Monticello could be preserved for his daughter Martha Randolph and her children. In a letter to a relative, she stated more practical views. She said that if anything could be saved, it should be the mills because they had more revenue potential. Then everything should be scaled down: most of the slaves sold, little furniture kept, and the family should relocate to property Jefferson owned in southern Virginia. Monticello would have to be sacrificed.

Once the bill passed and the property was appraised, Jeff Randolph engaged lottery brokers Yates and McIntyre of New York. There were to be 11,477 tickets offered at $10 each, with the prizes the Monticello estate, the Shadwell mills, and one-third of Jefferson’s Albemarle County lands.

Word of Jefferson’s situation spread, and concerned citizens of New York City, under the leadership of Mayor Philip Hone, persuaded Jeff Randolph that the money could be raised by public subscription in a manner far more dignified than a lottery. Committees were formed in New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, and meetings were conducted in Virginia as well. Approximately $16,500 was raised in a relatively short period. This was a small amount compared with a total debt calculated at more than $100,000, but it cheered Jefferson immensely to think that the American populace had not forgotten him.

With the prospect of a public subscription, the lottery was put aside. More might have resulted from these private donations, but following the news of Jefferson’s death on July 4, 1826, they soon diminished to nothing. The concern felt for an old patriot did not extend to his relatives.

Jeff Randolph determined to revive the lottery and asked Yates and McIntyre to advertise tickets in the Richmond Enquirer late in July and again in September and October. In early 1827, he traveled to Washington to petition Congress for an act that would make the lottery national, but without success. Exactly when Jeff Randolph let go of the idea is unclear, but on February 20, 1828, James Madison wrote to the Marquis de Lafayette that “the lottery owing to several causes has entirely failed.”

The sale of Monticello with an adjoining 552 acres was completed in November 1831. Its enslaved community had already been sold, as well as parcels of land, household furniture, livestock, and farming implements. Jefferson’s art collection was sent to the Boston Athenaeum for sale there, but it garnered little interest. The exact amount of the debt liquidated by these sales is not known. Jeff Randolph assumed the remainder of his grandfather’s debt.

Thomas Jefferson hated debt. He believed it compromised freedom of choice, whether attached to an individual or to a nation. As president, he was proud of reducing the national debt. In his personal finances, he was never so successful.

Extra Images

Gaye Wilson is a senior historian at the Robert H. Smith International Center for Jefferson Studies. She has written and published articles on a variety of Jefferson topics. Her long-term project and forthcoming book is on the Jefferson image as revealed in his life portraits.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Edwin Morris Betts and James A. Bear Jr., eds., The Family Letters of Thomas Jefferson (Charlottesville, VA, 1966).

- T. H. Breen, Tobacco Culture: The Mentality of the Great Tidewater Planters on the Eve of Revolution (Princeton, NJ, 1985).

- David Hancock, Citizens of the World: London Merchants and the Integration of the British Atlantic Community, 1735-1785 (Cambridge, 1995).

- Herbert E. Sloan, Principle and Interest: Thomas Jefferson and the Problem of Debt (Charlottesville, VA, 1995).

- Jefferson's Tardy Constitution

- Captain Jack Jouett's Ride to the Rescue

- Thomas Jefferson, Son of Virginia