Of Rocks, Trees, Rifles, and Militia

Thoughts on Eighteenth-Century Military Tactics

Text by Christopher Geist

Photos by Dave Doody

The popular image of militia in the Revolution was of sniping from the woods at British soldiers in the open. Behind the trees, Richard Frazier, George Suiter, and Richard Sullivan, from left, pick off the redcoats. Such action seldom occurred.

Dale Smoot, Josh Bucchioni, Chris Geist, Terry Yemm are among the militia interpreters parading across Market Square with their Magazine weapons.

Reenactors portray the redcoats in their standard lines of battle: rows of infantrymen, bayonets fixed to muskets, who loaded and fired in quick order.

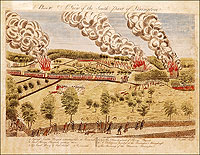

A contemporary print of the retreat to Lexington shows the uncommon example of guerilla tactics in which militia picked off the sitting redcoat targets. More often than not, American Continentals faced their enemy in the same ordered lines on the field.

Trained by the German Baron von Steuben in largely conventional European warfare—open-field battle by opposing lines— Washington’s regulars held their own against the British at the Battle of Monmouth in New Jersey in this nineteenth-century print.

Maybe you remember that early Bill Cosby routine about American history. It began like this:

"Suppose way back in history if you had a referee before every war, and the guy called the toss. Let’s go to the Revolutionary War."

[Referee speaking] "British call heads. It’s tails. What do you do, settlers? . . . Settlers say that during the war they will wear any color clothes that they want to, shoot from behind the rocks and trees and everywhere. Says your team must wear red and march in a straight line."

We laugh because Cosby tapped one of the most tenacious and cherished myths of the Revolution: American colonists prevailed in the conflict against, arguably, the finest military force of the era by using frontier tactics. American militia, or minutemen, rushed forth whenever the alarm sounded to confront the brightly dressed British regulars, who marched across the battlefield in tightly bunched formation, offering easy targets. Colonists hid behind rocks, trees, and fences and used their superior rifles to wreak havoc on the advancing redcoats, who were armed with inaccurate smoothbore muskets.

Rocks, trees, rifles, and valiant militia. The Revolution in a nutshell. A great comedy routine, perhaps, and certainly an inspiring legend to which many modern Americans subscribe, but this version of history is largely erroneous.

Interpreters at Colonial Williamsburg’s Magazine and Guardhouse help guests develop a more complex and complete understanding of eighteenth-century military tactics and how reality varies from popular mythology.

The rocks, rifles, and militia scenario originated with the story of Lexington and Concord, April 19, 1775, the skirmishes that started the fighting. British redcoats did indeed face colonial militiamen in linear formation. As the British force retreated to Boston, the colonists, armed with their own civilian weapons, sniped at their antagonists from behind fences and trees rather than confronting the professionals in formal lines of battle. With such guerilla tactics, the militiamen killed and wounded more British soldiers than British soldiers killed and wounded Americans. But the majority of the prominent battles of the war were contested quite differently.

Massed forces, British and patriot, in the linear formations at which Cosby’s monologue pokes fun, fought the battles of Long Island, Brandywine, Monmouth Courthouse, Hobkirk’s Hill, White Plains, Germantown, Camden, and Cowpens, to name a few. Sometimes, as these engagements evolved, one side or the other retreated in disarray, and some soldiers sought protection behind fences or trees or other defensive barriers. But the battle plans developed by the generals relied on linear tactics in the European fashion that dominated eighteenth-century warfare.

The concept of linear tactics is counterintuitive. It is almost ridiculous that two armies would face one another at less than a hundred yards in tight formations, three ranks deep, firing volley after volley. As they shot, they moved closer together, often closing the fight with a bayonet charge as one force drove the other from the field. Clumped, the soldiers seemingly offered their foes a classic “sitting duck” target. But this was true of both sides. Why then did eighteenth-century armies adopt such tactics?

American officers with prior military experience had learned the art of warfare under British commanders in the French and Indian War and other North American actions. Certainly, this was true of George Washington and many of his staff. Others, including Horatio Gates, were Englishmen who had served in the British army. When these men studied the art of warfare, they naturally were drawn to the writings of British tacticians and historians. The American foe of the Revolution had once been comrade and teacher.

But that just puts the question at one remove.

The answer is in the arms the armies used. The smoothbore military musket—the English version came to be known as the Brown Bess—is often maligned for inaccuracy, though the weapon was true enough at short range, say less than eighty yards. Yet accuracy was not at all the issue. Rate of fire, with companies firing in volley, gave muskets their military advantage. A well-drilled company could load and fire in unison at least four times a minute, and some seasoned units probably did better. No soldier aimed his weapon at any single adversary. He “presented” his weapon straight ahead, or obliquely to the right or left, at the command of his officers, and fired in unison with his company as rapidly as possible.

As a modern historian has written,

“Speed was everything. Speed for the defending force to pour as many bullets into the attacking force as possible; speed for the attacking force to close with its adversary before it had been too severely decimated to have sufficient strength to carry the position. . . .”

Linear positioning and rapid volleys explain the significance of the contributions to the American cause of Baron Friedrich von Steuben. Joining Washington’s regulars in their winter encampment at Valley Forge in February 1778, the German baron somewhat simplified the British manual of arms and used the new manual to drill the Continental force relentlessly and effectively in rapid loading and firing of the musket. He improved their battlefield maneuverability, too. Historian Douglas Southall Freeman called von Steuben the “first teacher” of the American army.

Rapidity of fire—sending constant, coordinated volleys in the direction of the enemy—was infinitely more important than the accuracy of any individual’s musket. Such firepower was hard to achieve unless the men were arrayed in open terrain and organized by company. So much for rocks and trees.

What about those rifles? These formidable firearms had been in use for about a hundred years before the Revolution, and they were plentiful in the southern and middle colonies, though relatively rare in New England. True enough, they were more accurate and effective at greater distances, several hundred yards, than were military muskets. But accuracy came at a price: rifles took too long to load. A minute or more was needed to tightly “patch” the ball and carefully ram it down the barrel to engage the rifled grooves that spun the ball and gave it true trajectory.

Moreover, unlike the riflemen, musketmen did not carry the powder horns used in the time-consuming measurement of powder for each charge. A musket’s charge, along with the ball, was measured and encased in a paper cartridge. The wrapper served as the ball’s wadding when it was quickly, though loosely, thrown down the barrel and pushed home with the rammer. The comparative sluggishness of reloading a rifle rendered it unsatisfactory for linear military tactics. Interpreter Dale Smoot says during his Magazine presentations, “Rifles are fine weapons for shooting at things that don’t shoot back—like deer.”

There was another problem with rifles and, indeed, all civilian long arms of the period. They were not fashioned to accommodate bayonets, an essential weapon of eighteenth-century infantry. Regular forces moved into lines of battle with bayonets fixed. Military bayonets were offset from the muzzle to permit loading and firing with the bayonets in place, always ready for a charge to force the enemy from the field. Civilian weapons might be equipped with plug bayonets, essentially knives with wooden plugs to be inserted into the barrel of the firearm, rendering it incapable of firing.

Even so, both sides used companies of riflemen as skirmishers sent forward to engage the enemy in advance of the bulk of the force. One or two such companies often were attached to each regiment. They proved effective as light infantry, companies with speed and mobility, carrying little equipment and used for scouting and rapid deployment over great distances. Virginia’s Daniel Morgan led such a rifle company to good effect at Saratoga. Early in the war, Morgan’s unit became known for traversing great distances quickly.

Still, such units played a small role in the development of the war. Opposing commanders hit upon an effective countermeasure when facing a rifle company. When Morgan’s riflemen approached Colonel Robert Abercromby’s British regulars on the field, Abercromby commanded his troops to charge the colonials with bayonets. Not a quarter of Morgan’s men had time to fire, and none of those to reload. Morgan’s unit fled in disarray.

Then there is the romantic mythology surrounding the American militia, those intrepid citizen-soldiers whose battlefield heroics faced down the finest army in the world. Problem is, as Washington himself knew from the beginning of the conflict, militia was undependable, poorly trained, and generally ineffective on the field of battle. They came armed with civilian weapons ranging from fine rifles to cheap trade muskets to fowling pieces—known today as shotguns. Within each of these categories of arms, there were differences among individual weapons. A unit equipped with almost as many different kinds of arms as soldiers could not load and rapidly fire volleys in unison.

In many of the colonies, militia laws specified a few days of annual training. Selection of militia officers was more often based on social status and charisma than on military experience and skill, and the colonies frequently were reluctant to send their militia units outside their borders. Militia units were notorious for leaving camp to tend to their lives as farmers or tradesmen. One militia unit apparently left the field immediately before the October 7, 1777, struggle at Saratoga. At Camden, South Carolina, August 16, 1780, the bulk of American forces was militia. British regulars charged the colonials with bayonets fixed, and the militiamen panicked, many dropping their loaded arms, never having fired a shot in one of the most decisive American defeats of the war.

Washington called the militia “a broken staff” and consistently pressed the Continental Congress to authorize the recruitment of regular troops. These recruits became the Continental Army with which he prosecuted the Revolution. He worried that militiamen possessed “an unconquerable desire of returning to their respective homes” and that “shameful and scandalous desertions” might harm the morale of the regulars.

In any conflict as long and complicated as the American Revolution there are, of course, exceptions to generalized description of hostilities. At the Battle of Cowpens in South Carolina, January 17, 1781, Morgan arrayed about 150 riflemen militia as skirmishers against British forces led by Banastre Tarleton. South Carolina militia was positioned 150 yards to their rear. Both of these lines were instructed to fire one volley, two if possible, and retreat. They were to fall back around the left and to the rear of the main body of regular Continentals arranged in line of battle on higher ground another 150 or so yards to the rear.

Tarleton accepted the bait, taking the withdrawing colonials for militiamen retreating in panic. Reaching the rear, the militia reloaded at their leisure, reorganized, and moved up to reinforce the regulars. British forces rushed headlong into Morgan’s trap and were decimated by the disciplined Americans. Tarleton lost about 100 killed and more than 800 captured, and Morgan demonstrated that militia could be used effectively in carefully planned and commanded situations.

At King’s Mountain, South Carolina, October 7, 1780, in one of the most atypical engagements of the Revolution, the two opposing forces were composed entirely of militia. There were loyalists from the Carolinas and elsewhere on the British side arrayed against militiamen from North Carolina and Virginia fighting for the American rebels. The only British national on the field was the commander of the Tories, Major Patrick Ferguson.

Ferguson’s men took up fortified positions on King’s Mountain and prepared to defend it. Armed mostly with rifles, the North Carolinians and Virginians advanced up the mountain under cover of the trees and rock outcroppings on its slopes. They loaded and fired from cover and did not concern themselves with formal battlefield tactics and volley fire. They won the field, Ferguson was killed, and the battle began the cascade of events that led the British army under Lord Charles Cornwallis to move northward toward its destiny in Virginia.

Defeated at Yorktown, Cornwallis wrote to his commander, Sir Henry Clinton,

“I will not say much in praise of the Militia of the Southern Colonies, but the list of British officers and Soldiers killed or wounded by them since last June, proves but too fatally that they are not wholly contemptible.”

Nevertheless, most battles intentionally initiated by either side in the Revolution were planned and contested with traditional European linear tactics. Little would change until the invention of the rifled musket and the Minnie ball shortly before the American Civil War. But that is another, quite grim story.

Christopher Geist, professor emeritus at Ohio’s Bowling Green State University, contributed to the autumn 2007 journal a story about English America’s first ironworks. He thanks Colonial Williamsburg’s Kevin Kelly, Ken Briner, Dale Smoot, and Bob Albergotti for their helpful suggestions for this article.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Jeremy Black, Warfare in the Eighteenth Century (London, 1999).

- Henry B. Carrington, Battles of the American Revolution (New York, 1887).

- Walter Edgar, Partisans and Redcoat: The Southern Conflict That Turned the Tide of the American Revolution (New York, 2001).

- Claude H. Van Tyne, The War of Independence (New York, 1929).