Searching the Arctic for What Wasn't There

It Took Centuries to Find the Northwest Passage

Text by James Breig

Photos by Dave Doody

A long-wished-for northern water route from Atlantic to Pacific promised greatly shortened voyages to trade for riches from the East. The Arctic yielded no ready access till recent summer melting of the polar cap.

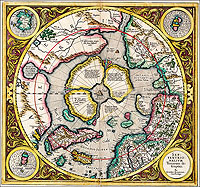

Gerard Mercator’s late sixteenth-century map of the Arctic and surrounding lands records attempts by explorers Frobisher and Davis to find the Northwest Passage. It was believed an inland lake or rivers allowed passage across the American continent.

Seen in part in this satellite photo and winding its way from the Atlantic through archipelagoes of the Canadian Arctic and on to the Bering Strait between Alaska and Russia, the Northwest Passage remained unnavigable because of ice until recent thawing.

In 1745, readers of the Virginia Gazette, a weekly newspaper published in Williamsburg, learned that back in England Parliament “had resolved to bring in a Bill to grant a Sum of Money to any Person or Persons who shall discover the N. West Passage.” Seven years later, the Gazette informed its audience that “an Officer of the Marine who has been twice or thrice at Greenland” had given “Reasons for supposing there is an open North West Passage into the South Seas.” After fifteen more years had passed, the newspaper said, “Great discoveries have been made relative to the North West passage.” After five additional years, subscribers saw that “the Government is preparing to send out Major Rogers . . . in Pursuit of the North West Passage.” Two decades later, the Gazette reported that the empress of Russia had dispatched three ships to attempt “the Discovery of the north west Passage to China.” A year later, two British ships were sailing “at the End of Spring . . . to discover a Northern Passage to the South Sea”—as the Pacific was called. When spring arrived, the paper said two French frigates were “fitting out at Brest . . . to attempt the north west passage” ahead of the British explorers.

Throughout the eighteenth century, explorers from Great Britain, Denmark, France, and Russia tried and failed to find the Northwest Passage, that is, a practical route from the Atlantic seaboard of America to the Pacific that would shorten the trade route between Europe and the Far East. All failed, but they were in storied company. Long before and long after their ventures, sailors and trailblazers tried to find the passage. In the twenty-first century, nature may be opening the way. The New York Times reported in October 2007, “The Arctic ice cap shrank so much this summer that waves briefly lapped along two long-imagined Arctic shipping routes, the Northwest Passage over Canada and the Northern Sea Route over Russia.”

For at least four centuries, finding the Northwest Passage was a dream like finding the golden fleece, the Holy Grail, the fountain of youth, and cities of gold. Uncovering a route from Europe to the Far East by sailing west inspired explorers, churchmen, businessmen, and governments seeking an easier path to glory, converts, goods, and power. John Logan Allen, author of Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest, wrote that the quest endured so long because the desire for such a route trumped its nonexistence. By the way, Lewis and Clark were looking to find an all-water route to the Pacific, too.

“A lot of geographical ideas,” Allen said, “are born out of desire: If you want something to be organized in a certain way, it will be—in your head. If you have a strong geographical imperative, you can say, ‘I don’t want to be confused by geographical facts.’

“The desire in this case belonged to European powers and businesses that were eager for a way to get their goods cheaply and quickly to the East, and return just as quickly and cheaply with Asian supplies.” Europeans “knew it was a rich area from the reports of Marco Polo and other travelers,” Allen said. “With the increase in agricultural production and population in the thirteenth to fifteenth centuries, Europe was looking for a source of raw materials, like lumber, and new markets.”

The sources included China, Japan, and Indonesia. The lure of the passage was that it offered a means “of getting the riches of the Orient for the markets of western Europe” and vice versa, said historian James Ronda. The western route seemed to guarantee “wealth and imperial power. Those are strong motives and enormously influential forces.”

In the late fifteenth century, the search motivated such navigators as Christopher Columbus and John Cabot. Cabot was attempting to find a simple way to the East when he ran into a 3,000-mile-wide obstacle: North America. The sixteenth and seventeenth centuries saw efforts by Martin Frobisher, Francis Drake, John Davis, Henry Hudson, William Baffin, and others who probed the eastern and western edges of the New World to find a waterway that connected the oceans.

In the seventeenth century, England established Jamestown in part to “gain the rich trade of the East India, and so cause it to be driven through the Continent of Virginia, part by Land and part by Water, and in a most gainfull way and safe, and far lesse expenceful and dangerous than now it is,” in the words of the 1649 Perfect Description of Virginia. Many of the Northwest Passage explorers would focus on the northern regions of North America in the belief that a polar passageway existed. Belief in it was so common that cartographers put it on their maps and named it the Strait of Anian.

The phrase “northwest passage” first appeared in print in the reports of Richard Hakluyt, a geographer who published Voyages in Search of the North-West Passage in 1587. He sought to prove there was a passage through America “to go to Cathay and the East Indies.” Cathay was another name for China. Citing Plato and Aristotle in support of his argument, Hakluyt said that learned men of the past “would never have so constantly affirmed” such a passage “if they had not had great good cause and many probable reasons to have led them thereunto.”

As the eighteenth century dawned, the long-sought-for route was as elusive as ever. In the Age of Reason, with its emphasis on scientific evidence and provable facts, the idea that the passage might be wishful thinking seemed to have occurred to few. A Spanish admiral recorded in his diary that the passage had “no other foundation than the madness or ignorance of someone devoid of all knowledge of either navigation or geography.” But he was an exception to what Ronda termed “the tenacity of illusion” and “the geography of hope,” which posited, “Because you want it to be there, it will be there.” And people wanted it to be there.

Scholar Philip V. Allingham said that “the matter of a direct sea route to Asia was always foremost in the minds of those controlling British naval exploration. . . . As Britain acquired colonial possessions in the Pacific and the former thirteen colonies became a national rival to British power on the North American continent, Britain’s discovery of a viable Northwest Passage loomed even larger in the minds of government officials.”

In the 1700s, adventurers, scientists, and military leaders had a couple of notions of what the passage was, John Allen said. “By the 1770s, it evolved into a configuration which includes either a large lake or inland sea in the middle of the continent, or a large river navigable to the interior,” where a pyramidal rise in the land would lead to another river rushing to the Pacific. With that notion and others in their minds, eighteenth-century explorers headed into terra incognita:

- In 1753, the Pennsylvania Gazette reported that Captain Charles Swaine had returned from his search for the passage with the news that “there is no communication with Hudson’s Bay through Labrador where one had here to fore imagined.”

- In 1778, Captain James Cook was ordered to “explore such rivers or inlets as may appear to be of a considerable extent and pointing towards Hudson Bay or Baffin Bay.”

- In 1789, Alexander Mackenzie set off on a trek across Canada in an attempt to find a combination of rivers, straits, and other waterways that would unlock the doors to Asia. He failed, but he did not give up.

- In 1781, J. Carver wrote in Travels through the Interior Parts of North America in the Years 1766, 1767, and 1768 that “a Northwest Passage, or a communication between Hudson’s Bay and the Pacific Ocean” could be found and result in “many useful discoveries.”

- In 1793, Mackenzie made it to the Pacific with a handful of Indian guides and fellow voyageurs. He painted his name on a rock to prove his arrival, but he had proved something else: how torturous the journey was, involving many portages and much walking, impediments to swift trade.

Colonial Williamsburg’s Willie Balderson as Meriwether Lewis discusses with Bill Barker’s Thomas Jefferson the proposed Lewis and Clark expedition to find, among other things, a usable water route through the continent to the Pacific. They did not find it.

Extra Image

Extra Image

- Willie Balderson

The search for the Northwest Passage, so fascinating to explorers, has intrigued authors and filmmakers, too. Allingham said, “Polar exploration captured the British imagination, as the opening of Conrad’s Heart of Darkness suggests. Dickens’s The Frozen Deep also attests to popular fascination with polar exploration.”

The search motivated Walt Whitman to pen an epic poem, “Passage to India,” a celebration of exploration and global unity. The mention in the Virginia Gazette of the real Major Robert Rogers undertaking a search for the passage has a fictional counterpart in Northwest Passage, a popular novel of the 1930s by Kenneth Roberts. When it was made into a 1940 movie starring Spencer Tracy as Rogers, the search for a passage was lost in a tale about the French and Indian War.

Among the books the Lewis and Clark expedition inspired was 1996’s Undaunted Courage by Stephen Ambrose. In 1997, Ken Burns, a documentary filmmaker, produced Lewis and Clark: The Journey of the Corps of Discovery. The duo’s trek got a fictionalized Hollywood treatment in The Far Horizons, a 1955 film starring Fred MacMurray and Charlton Heston as the explorers.

The Founding Fathers were not immune to passage-mania. George Washington believed that the Potomac, which flowed past Mount Vernon, was the beginning of a series of rivers that would transport goods a long distance. A Frenchman assured Washington that “it is less difficult to discover the Northwest Passage than to create a people, as you have done.” Thomas Jefferson told James Madison that “the Ohio, and its branches which head up against the Patowmac, affords the shortest water communication by 500 miles of any which can ever be got between the Western waters and Atlantic.” Jefferson had a long-standing curiosity about the western expanses that began at Virginia’s border, a curiosity perhaps inherited from his father, Peter, who had surveyed the Old Dominion’s interior and sought land grants beyond the Allegheny Mountains. In 1793, the year Mackenzie moved toward the setting sun, Jefferson financially supported a French botanist’s plan, eventually aborted, to “find the shortest & most convenient route of communication between the U.S. & the Pacific Ocean.”

As the eighteenth century gave way to the nineteenth, President Jefferson launched a search for the passage by commissioning Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their Corps of Discovery to walk, ride, portage, row, and sail from the middle of the United States to the Pacific and back. The purpose of the expedition, Jefferson wrote, was

to explore the Missouri River, and such principal streams of it, as, by its course and communication with the waters of the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregan, Colrado, or any other river, may offer the most direct and practicable water-communication across the continent, for the purposes of commerce.

For all of its successes in charting rivers, establishing contacts with Native Americans, chronicling flora and fauna, and reaching the Pacific, the expedition failed in its main goal. With the jagged, jutting Rockies blocking the way and meandering, rapids-riddled rivers not connecting with one another, Lewis and Clark did not find a simple way to get across the continent.

Nevertheless, fascination with the Northwest Passage did not wane. Much of the exploration was in the Canadian Arctic, a region that had shorter latitudes and was dotted with a watery maze of islands through which ships could pass when the ice receded. One of the most elaborate attempts was Sir John Franklin’s 1845 expedition with more than 120 men on two ships, Erebus and Terror. The vessels were laden with three years’ supplies, including nearly five tons of chocolate and 2,400 books. The crew disappeared, and rescue missions found only traces of them. Some historians believe ice death-gripped the ships for two years.

As the twentieth century began, the search captivated Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, who admired Franklin but opted for an approach that was the polar opposite. To traverse the Arctic, Amundsen took a handful of men aboard a small boat, Gjoa, with relatively few supplies. His notion was to eliminate the need for enormous crafts loaded with tons of goods; instead, the explorers would forage for food and build shelters, as the native Inuits did. In 1905, two years after he left Oslo, Amundsen encountered an American whaler, confirming that he had crossed from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

That led some people to declare that he had discovered the Northwest Passage; but, if the passage is defined as an easy, practical, and repeatable route, Amundsen fell short.

With the invention of submarines came another method of making the passage: instead of fighting against the implacable ice, a craft could slide underneath it. The United States sub Nautilus did just that in the 1950s when it reached the North Pole. Still, a simple route had not been charted.

It is a debatable point whether the Northwest Passage has been found. Looked at another way, however, it has been discovered several times. James Ronda said, “There are different kinds of passages, and they have changed dramatically from the fifteenth century to our own time. There have been trails, rails, and the interstate highway system. Each of these takes objects from the Atlantic to the Pacific. The idea is still very much alive. It’s one of the most enduring ideas—and illusions—in the history of American geography.”

John Allen said the transcontinental railroad in the middle of the 1800s was “the penultimate gasp of the Northwest Passage idea, with the completion of the interstate highway system” as the idea’s twentieth-century finale.

In these efforts through the centuries, Philip Allingham finds recognition that nature could be a powerful enemy. “The third-generation Romantics, including Tennyson and Dickens,” he said, “reluctantly acknowledged that Nature was not the benign deity she seemed in the south of England and the Lake District. Rather, as the Franklin Expedition’s members and the various search parties learned through excruciating experience, she was terrible, fearsome, and utterly inimical to European intrusion.

“In the North, no trees grew, ice retreated for only a month, towering ice floes could crush European vessels as if they were match-sticks, and only the aboriginals, superbly adapted to such a harsh environment by generations of experience, could survive temperatures below what had been the theoretical minimum of zero Fahrenheit. The creation and maintenance of Empire, the British realized, required an heroic endurance and sacrifice that were, as in the case of the Franklin Expedition, sometimes quite pointless.

“Perhaps, then, the greatest contribution of the Northwest Passage was undermining the popular appreciation of imperialism” as incapable of defeat and failure.

In the end, nature may uncover what man could not. After thwarting explorers for centuries, nature may be opening the Northwest Passage. Because of global warming, whether caused by human activity or the cycles of weather, Arctic ice is receding. Some scientists say the route westward could be open within a few years and slice the crossing from Atlantic to Pacific by thousands of miles.

With that possibility in mind, Prime Minister Stephen Harper of Canada preemptively told the United States in 2006 that his nation owned something that had previously been a chimera: the long-sought Northwest Passage.

View a clip about the Northwest Passage from Colonial Williamsburg's 2005 Electronic Field Trip "Jefferson's West."

Small - Quicktime (912kb

Small - Windows Media Player (900kb)

Large - Quicktime (1.5Mb)

Large - Windows Media Player (1.7Mb)

James Breig, is an Albany-based writer who contributed to the Holiday 2007 journal an article on Williamsburg weddings.

Suggestions for further reading:

- John Logan Allen, Lewis and Clark and the Image of the American Northwest (Urbana, IL, 1975).

- Harold B. Gill and Joanne Young, eds., Searching for the Franklin Expedition: The Arctic Journal of Robert Randolph Carter (Annapolis, MD, 1998).

- Glyn Williams, Voyages of Delusion: The Quest for the Northwest Passage (New Haven, CT, 2003).

Extra image

Extra image