Gossip, Flattery, and Flirtation

The Art of Eighteenth-Century Letter Writing

by Andrew Gardner

Online Extras

Sidebar: The Quill Pen

Write with a Quill Pen

Extra Images

Eighteenth-century lovers—and bill collectors, parents, and others tongue-tied on paper—had literary help from published collections of model letters. Adam Wright borrows a heart-softening phrase or two to woo his sweetheart, Erin Wright, below.

Printer—later, novelist—Samuel Richardson profited from a desire for self-improvement and social advance in his Familiar Letters

Before email and cell phones, lovers spoke through the handwritten word. Camilla ponders her sweetheart's plan for elopement in a 1796 print.

The letter woman rang her bell to collect mail for the post. The lad, alas, doesn't have his penny for the letter.

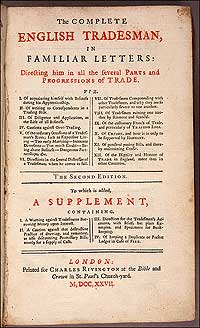

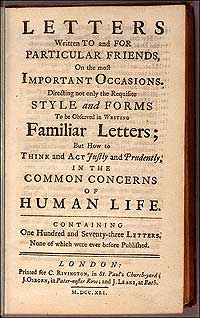

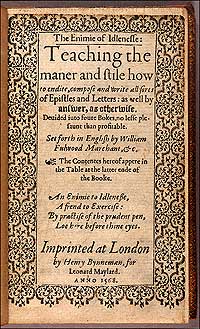

English letter writers had advice and templates for composition from Fulwood's Enimie of Idleness and Defoe's English Tradesman.

In a world of instant messaging, emails, cell phones, and faxes, there is something uplifting about opening the old-fashioned mailbox and discovering, beneath the bank statements, utility bills, and junk mail, a handwritten letter from a friend, a relative, or a lover. Getting a letter—not the announcement of another sale or the offer of another credit card, but an envelope of personal correspondence written in a familiar hand, a genuine letter—is gratification. The ancient Chinese had a proverb: "A letter from home is worth ten thousand ounces of gold." Seventeenth-century poet John Donne said: "Sir, more than kisses, letters mingle souls. For thus friends absent speak." For Thomas Jefferson, letters from friends and family were "like gleams of light, to cheer a dreary scene."

If the humble longhand epistle is, during the twenty-first century, on the road to quaintness, in the eighteenth century it epitomized communication.

In the class-conscious society of the 1700s, where people knew their places, social climbing—whether to a good position in the world of work, or a spouse with prospects—required a facility with words and the ability to write them down with decorum, flourish, and the requisite degree of humility. A young person's education paid attention to schooling in penmanship and art in composition. But for many a poor lad and lass, education was basic or beyond reach.

An eighteenth-century equivalent to The Dummies' Guide to Letter Writing was needed. Daniel Defoe was one of the early entrepreneurs to sell tickets on the self-help bandwagon. His 1726 Complete English Tradesman gives notes on to how to pen proper letters. He said, "An easy and free way of writing is the best style for a tradesman." But "he that affects a rambling and bombast style, and fills his letters with long harangues, compliments and flourishes, should turn poet instead of tradesman, and set up for a wit not a shopkeeper."

In 1568, William Fulwood had written The Enimie of Idleness: Teaching the maner and stile how to endite, compose and write all sorts of Epistles and Letters. Next century, an author identified only by the initials W. P. wrote A Flying Post With a packet of Choice new Letters and Compliments: containing Variety of Examples of Witty and Delightful Letters upon all occasions both of Love and Business, which appeared in bookshops in 1678.

By the mid-1700s, these guides were in need of an update. In 1741, Samuel Richardson, a master printer, wrote and published Familiar Letters for Important Occasions. That was the short title, which in its fullness read: Letters Written to and for Particular Friends on the Most Important Occasions Directing not only the Requisite Style and Forms to be Observed in Writing Familiar Letters; But how to think and act Justly and Prudently in the Common Concerns of Human Life.

Richardson said he began his book after becoming privy to the love secrets of three young women who asked him to make up words to answer their sweethearts' letters. Later in life, Richardson capitalized on his letter-writing skills, as well as shorter, punchier titles, and wrote Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded and Clarissa—the earliest true novels published. Lengthy, romantic bodice rippers, they are moral tales whose plots unfold purely from the content of letters written between the principal characters.

Richardson's Familiar Letters became a popular cheat sheet to help anyone composing a letter on a wide and—from a twenty-first-century perspective—intriguing range of situations. The 173 letters in the book provide one of the most complete insights into the life and times of eighteenth-century society assembled. The letters allow us to grasp what made the 1700s world tick, the hopes and fears, and what issues were uppermost in people's minds. Scanning these Familiar Letters, it is possible to get a sense of how different their world was from ours.

There are the to-be-expected letters of condolence and letters demanding bills to be settled: "To a country correspondent, modestly requesting a balance of accounts between them." There is gritty, heartfelt advice aplenty from "a Father to a Son, to dissuade him from the vice of drinking to excess" and from "a Son reduced by his own extravagance, requesting his fathers advice on his intention to turn player." The father's answer, "setting forth the Inconveniences and disgrace attending the profession of Player," leaves nobody in doubt about the uphill battle actors of the era faced:

You must be obsequious to a degree of slavery. Not one of an audience that is able to hiss, but you must fear...More satisfaction, more ease, and more profit may be got in many other stations, without the mortifying sense of being deemed a vagrant by the laws of your country.

In a similar vein, there are warnings to be careful in the big, bad city. A melodramatic letter from "A Young woman in Town to her sister in the country recounting her narrow Escape from a Snare laid for her on her first arrival, by a wicked Procuress" recounts a near tragedy. You can almost feel the fans afluttering and smell the smelling salts as the poor, innocent country lass relives the dreadful memory of her fleeting brush with a sinful and dastardly brothel owner. And there are plenty of reminders not to rock the boat as far as personal conduct is concerned. A letter from an uncle to his tomboy niece Betsy rails "Against a young lady's affecting manly airs; and also censuring the modern Riding-habits." The uncle says some conformity to fashion is allowable, "but a cock'd hat a lac'd jacket, a fop's peruke, what a strange metamorphoses do they make...I know of nothing that would become either the air or the dress but a young Italian singer."

But most of Richardson's letters, and the most absorbing, concern affairs of the human heart. Reading the titles, anyone would be forgiven for thinking they had picked up a Harlequin romance:

· "From a Father To a daughter against a frothy French Lover"

· "To a young fellow who makes Love in a Romantic manner."

· "A gentleman to a lady who humorously resents his Mistress's fondness of a Monkey, and indifference to himself."

· "From a young maiden abandoned by her lover for the sake of a greater fortune."

· "From a young lady to her Father, acquainting him with a proposal of marriage made to her."

· "A lady to a Gentleman of superior Fortune, who, after a long Address in an honourable way, proposes to live with her as a Gallant."

Richardson's Familiar Letters was perhaps the most conservative and proper text of its kind for its times. But at the beginning of the 1700s anyone looking to improve their epistolary skills referred to The Lover's Secretary, written by Thomas Brown, "Being a Collection of Billets Doux, Letters Amorous, Letters tender, and letters of praise, Collected from the Greatest Wits of France."

This book's pedigree reaches to a mid-seventeenth-century French writer who had penned the erotic Lettres Portugaise, which had been translated into English and published under the title Five Love Letters from a Nun to a Cavalier. Sales were brisk, and risqué imitations began to appear. Some were little more than pamphlets, reminiscent of the small, cheap booklets sold at checkouts in our twenty-first-century supermarkets, or even the forerunners of articles that might appear in Cosmopolitan, e.g., "One hundred things to say to turn Him On."

One such eighteenth-century pamphlet was The Amorous Gallant's Tongue Tipp'd with Golden Expressions: or, the Art of Courtship Refined. Written anonymously, it gave men and women lessons in the art of waxing eloquent while whispering sweet nothings. For any would-be gallant—eligible bachelor—suffering from lovesickness, or old-fashioned lust, who hadn't a way with words, these helpful tips must have been a godsend. The pamphlets could be relied on to suggest a few good lines worthy of any red-blooded, tongue-tied ploughman or soldier struck temporarily dumb by the unspoken love for someone of the opposite sex.

For openers there was a sentiment as fine as any to be sent through the eighteenth-century mails: "Your beauty is the pole star of my Soul and brings my wandering Heart toss'd on the billows of Inconstancy, to the desired Haven of its rest." Then to complete a quick double whammy, you could add: "Your beauty is the Clue that guides my Heart thro' all the winding Labrynths of Love," or "at the sight of your bright Eyes, my Heart was quickly pierced and I straightways became your Captive."

At this point, any eager, lovesick male suitor putting pen to paper might be feeling rather pleased with his literary prowess. Although the high-octane sentiments were not exactly original, it was always hoped they would cast a magic spell and raise the temperature of the letter, and its recipient, to a boiling point. Any doubters who reckoned they had not adequately tweaked the interest of their hearts' desires, however, could add a postscript. Perhaps something light and fluffy, along the lines of: "Your Goodness like the Sun's benign Rays, chears my despairing Soul, and makes me hope in Spite of my Unworthiness."

If another suitor vying for the same fair maiden's hand copied out the same flatteries from the same pamphlet, there might be a bit of explaining to do.

From making declarations of undying love to recording everyday small talk, the art of letter writing blossomed in the eighteenth century. Postal services helped personal correspondence become part of a popular culture that lasted nigh on three hundred years. In its heyday, letter writing, a finely honed entertainment universally appreciated, could carry scandal, gossip, and the minutiae of the lives and loves of family and friends.

Jefferson said, "Do not write me studied letters, but ramble as you please." And Jonathan Swift so liked well-written personal correspondence that he was in the habit of sharing the pages with his drinking chums. "When I receive a letter from you," he wrote to an old friend, "I summon a few very particular friends who have good taste and invite them to share it, as I would do if you had sent me a haunch of venison."

Swift, Pope, Dr. Johnson, James Bos-well, and Jane Austen came to publish their letters, making public their private thoughts. But these everyday words are so charged with wit, clarity, force of argument and a sense of self-assurance that they have a magical quality that raises them from something that often was used to start a fire in the hearth to the realm of cherished literature.

Yet one of the great letter writers, Dr. Samuel Johnson, whose life spanned some seventy-five years of the eighteenth century, had reservations about having his correspondence made public. "In a man's letters," Johnson said, "his soul lies naked, his letters are only the mirror of his breast. Whatever passes within him is shown in its natural process. Nothing is inverted, nothing distorted."

Johnson was seldom wrong about anything. So maybe emails aren't so bad after all. They come with a delete key.

Andrew Gardner lives and writes on Salt Spring Island off Canada's west coast. He contributed to the Holiday 2006 journal a story on turkeys.

Suggestions for further reading:

The Familiar Letter in the Eighteenth Century, ed. Howard Anderson, Philip B. Daghlian, and Irvin Ehrenpreis (Lawrence, KS, 1966).

Samuel Richardson, Familiar Letters on Important Occasions (1st ed., 1741; reprt. London, 1928).