"Such a dish as powdered wife I never heard of"

By Dennis Montgomery

When hunger-mad colonists turned to eating human flesh during Jamestown's Starving Time, some were said to "lay wait and threatened to kill and eat" those who seemed better nourished. From left, Patrick Strawderman is stalked by Dennis Farmer and Lindsay Gray.

ACCOUNTS of Jamestown anthropophagy have never, shall we say, been palatable. As horrific in the seventeenth century as they are in the twenty-first, reports of man-eating were, nevertheless, as readily accepted and credited then as they are quickly doubted and discounted now.

Perhaps it's because today they come as something of a surprise.

The earliest relations of Virginia made no bones about it: In the winter of 1609–10, the Starving Time, the English were reduced to consuming, as colony President George Percy put it, what they "could come by." And not for the last time.

Modern writers, however, are more circumspect; so tactful, in the main, that modern readers and students have seldom heard of such a thing, and commonly disbelieve it when they do. At that, some ask what purpose is served by recalling these ancient unpleasantnesses when there are to be recounted more inspiring, and less embarrassing, passages in the Jamestown saga.

That would leave the saga incomplete, like telling the story of the Truckee Pass and not mentioning the Donner Party. Without it, the understanding of how narrow were Jamestown's circumstances and what it took to create America's first permanent English settlement would be less than fully formed.

News of Jamestown cannibalism arrived in England with a runagate crew of settlers and circulated widely. It reached the ears of the Spanish ambassador, who wrote June 14, 1610, to his king:

Sire—From Virginia there has come to Lyme, a harbor of this Kingdom, a ship of those that remained there lately, and those who arrived in it, report that the Indians hold the English surrounded in the strong place which they had erected there, having killed the larger part of them, and the others were left so entirely without provisions that they thought it impossible to escape, because the survivors eat the dead, and when one of the natives died fighting, they dug him up again, two days afterward, to be eaten.Among other tales, the Jamestown deserters, who had stolen off in a small vessel named the Swallow, retailed a story of a man who devoured his wife. In the years to come, nearly every time the story appeared in print, more details were disclosed.

The Virginia Company of London, the joint-stock enterprise that ran the colony, got it to the press first, that December. In A Declaration of the Estate of the Colony in Virginia, with a confutation of such Scandalous Reports as have tended to the disgrace of so worthy an enterprise, a promotional tract that downplayed the starving and the cannibalism, the company said:

There was one of the company who mortally hated his wife and therefore secretly killed her, then cut her in pieces and hid her in divers parts of his house. When the woman was missing, the man suspected, his house searched, and parts of her mangled body were discovered. To excuse himself he said that his wife died, that he hid her to satisfy his hunger, and that he fed daily upon her. Upon this, his house was again searched, where they found a good quantity of meal, oatmeal, beans, and peas. He thereupon was arraigned, confessed the murder, and was burned for his horrible villainy.This version of the tale came by way of Sir Thomas Gates, the colony's new governor.

The company staggered to its death in 1624, the year a group of Virginia survivors wrote A Brief Declaration of the Plantation of Virginia during the first Twelve Years . . . down to this present time. It said famine had compelled them to consume

those Hogs, Dogs & horses that were then in the Colony, together with rats, mice, snakes, or what vermin or carrion soever we could light on, as also Toad-stools, Jewes ears, or what else we found growing upon the ground that would fill either mouth or belly; and were driven through unsufferable hunger unnaturally to eat those things which nature most abhorred, the flesh and excrements of man, as well of our own nation as of an Indian, digged by some out of his grave after he had lain buried three days & wholly devoured him; others, envying the better state of body of any whom hunger had not yet so much wasted as their own, lay wait and threatened to kill and eat them; one among the rest slew his wife as she slept in his bosom, cut her in pieces, powdered her & fed upon her till he had clean devoured all parts saving her head & was for so barbarous a fact and cruelty justly executed. Some adventuring to seek relief in the woods, died as they sought it, & were eaten by others who found them dead.

By "powdered," they meant salted.

Virginia's General Assembly that year inscribed in its minutes:

One man out of the misery he endured, killing his wife powdered her up to eat her, for which he was burned. Many besides fed on the Corpses of dead men, and one who had gotten unsatiable, out of custom to that food could not be restrained, until such time as he was executed for it.

Captain John Smith left Virginia before the colonist ate the wife but collected a report of the affair to flesh out his General History of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles, which fell from the press in 1624.

Nay, so great was our famine, that a Salvage we slew, and buried, the poorer sort took him up again and eat him, and so did divers one another boiled and stewed with roots and herbs: And one amongst the rest did kill his wife, powdered her, and had eaten part of her before it was known, for which he was executed, as he well deserved; now whether she was better roasted, boiled or carbonado'd, I know not, but of such a dish as powdered wife I never heard of.

By "carbonado'd," Smith meant barbequed.

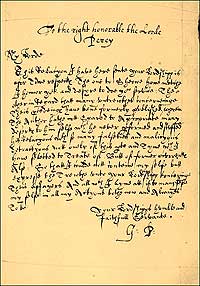

The dedication of Percy's Trewe Relaycion, which recounted the desperate acts and official retributions of the Starving Time.

Percy the same year penned A True Relation, though not all of it reached print until the 1930s. Among other things, Percy said:

This was most Lamentable That one of our Colony murdered his wife Ripped the childe out of her womb and threw it into the River and after chopped the Mother in pieces and salted her for his food. The same not being discovered before he had eaten Part thereof.It was not the last Virginia-related case of cannibalism in extremis. Bermuda, claimed for England by settlers shipwrecked on the way to Jamestown, knew one in 1615. Smith reported that seven men, among them Andrew Hilliard, fishing from a boat, were blown by a tempest to sea. Six died, five of them to be buried in the ocean. Hilliard could not push overboard the last,

for so weak he was grown he could not turn him over as the rest, whereupon he stripped him, ripping his belly with his knife, throwing his bowels into the water, he spread his body abroad tilted open with a stick, and so lets it lie as a cistern to receive some lucky rain-water, and this God sent him presently after, so that in one small shower he recovered about four spoonfuls of rain water to his unspeakable refreshment; he also preserved near half a pint of blood in a shoe, which he did sparingly drink of to moist his mouth: two several days he fed on his flesh, to the quantity of a pound.There was at least one more instance of Virginia-related cannibalism. In January 1649 sixteen men and three women fleeing to Jamestown from Cromwell's Protectorate were marooned by the crew of the Virginia Merchant on an island off the Eastern Shore. Provisions aboard had run so short that rats trapped in the bilges were prized. The castaways, among them Colonel Henry Norwood, kept starvation at bay for six days on rations of oysters and birds until supplies failed. Norwood, chosen leader, counseled cannibalism:

Of the three weak women before mentioned, one had the envied happiness to die about this time; and it was my advice to the survivors, who were following her apace, to endeavor their own preservation by converting her dead carcass into food, as they did to good effect. The same counsel was embraced by those of our sex: the living fed upon the dead; four of our company having the happiness to end their miserable lives on Sunday night the day of January.Indians rescued the survivors five days later, and the English made their way to settlements in February.

There are, then, a half-dozen written seventeenth-century reports of Starving Time cannibalism, each of which corroborates another in one or more details. Two documents have the multiple endorsements of resident Virginians—the colony's legislature and Starving Time survivors. The company's account of the man who ate his wife is backed not only by the authority of Jamestown's president at the time but his successor's, not to mention the men of the Swallow.

How widespread was the Starving Time cannibalism? For sure, if the records are to be believed, a Native American, an Englishwoman, and more than one Englishman were killed and consumed. We are told, "Many besides fed on the Corpses of dead men" and that "Some adventuring to seek relief in the woods, died as they sought it, & were eaten by others who found them dead." "Many" is an indefinite word, but, by the usage of dictionaries then and now, designates a large number. More than that, no one can say.