Finding Slaves in Unexpected Places

Keeping Blacks in Bondage Was Not a Southern Monopoly

by James Breig

An early casualty of the Revolution was a runaway slave, Crispus Attucks, killed by British soldiers in the "Boston Massacre."

AMONG THE MINUTEMEN who turned out on Lexington Green on April 19, 1775, to confront the British and start the fight for American freedom was Prince Estabrook, a black man and a slave. He was wounded in the shoulder. Five years before, runaway slave Crispus Attucks was among five men slain by British soldiers in the Boston Massacre, a confrontation he may have rashly initiated.

Some modern Americans might guess that Estabrook and Attucks were southern slaves visiting New England with their masters, but they were Massachusetts residents, two of the hundreds of thousands of men, women, and children in northern bondage during the eighteenth century. In the early 1700s, slaves were one-sixth of Philadelphia's population. A New York visitor around the time of the Revolution said that "it rather hurts an European eye to see so many Negro slaves upon the street." At the time, there were as many as half a million slaves in the northern colonies, about 20 percent of the population. When the newborn United States took its first census in 1790, there were still more than 2,600 slaves in Connecticut, nearly 9,000 in Delaware, 11,000-plus in New Jersey, and almost 22,000 in New York.

The history of northern slavery almost exactly coincides with the 100 years of the eighteenth century, from an increasing reliance on slave labor as the century dawned to New York's 1799 law that set in motion the slow manumission of slaves in that state.

According to Leslie M. Harris, an Emory University history professor, the first non–Native American settler in Manhattan was a free black man: Jan Rodrigues, a sailor marooned in 1613 by a Dutch vessel. Her book, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863, tells how Rodrigues married into an Indian tribe and became a negotiator between it and Dutch traders. After Peter Minuit bought Manhattan in 1626, more settlers arrived and brought eleven slaves with them—just seven years after the first Africans landed in Virginia.

In 1664, when England took control of New Netherland and renamed it New York, slavery expanded on a rising need for cheap labor to improve the colony and the Duke of York's financial interest in the Royal African Company, which ran the English slave trade. Harris writes that between 1698 and 1738, New York's slave population "increased at a faster rate than did the white population." In 1702, New Jersey Governor Edward Cornbury was told by British authorities to make sure "a constant and sufficient supply of merchantable Negroes" was available "at moderate prices."

Though once the law forbade the enslavement of black Christians, the exemption was written off the books. Slavery was limited to African Americans. The number of slaves who could congregate, and when, was restricted—rules that reflected white fear of slave rebellions hatched at night by conspiratorial mobs of oppressed people.

Nevertheless, many northern masters permitted their slaves to own property, to inherit from their owners, and to cultivate small plots of land and sell the crops for spending money or to purchase freedom. An indentured white man in the North said that he and his peers had it worse than slaves because "they universally almost have one day in seven whether to rest or to go to church or see their country folks—but we are commonly compelled to work as hard every Sunday." Ira Berlin, a University of Maryland history professor and author of Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America, writes that the work of northern slaves was less demanding than the labor required on plantations in the Sugar Islands, the Chesapeake region, and the Deep South. "The demand to produce" in those areas was fierce, he said, and slaves were "pressed to work many more hours with fewer days off." Southern and Caribbean plantation owners "could work slaves to death and purchase more," Berlin said. The annual mortality rate on some sugar plantations rose to 17 percent. Berlin called the plantations "killing machines."

Most northern slaves worked on farms, but some were skilled at trades, trained in tailoring, sailmaking, carpentry, and such. Others toiled in tanning factories, iron manufacturing, and fishing. Some were permitted to arrange for their own sale, a concession that allowed them to reunite with relatives or to find kinder masters. New Yorker Aaron Burr's mother, Esther, wrote in a letter that "our Negroes are gone to seek a master. Really ...I shall be thankful if I can get rid of them."

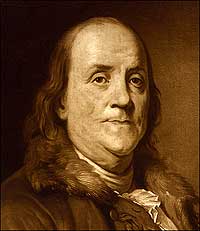

North and south, America's founders had a commitment to human rights and to slaves. Pennsylvania's Benjamin Franklin, Massachusetts's John Hancock, and New York's John Jay, for example, owned people. Like George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, they recognized the contradiction between advancing the cause of freedom and holding slaves, and they sought to resolve it.

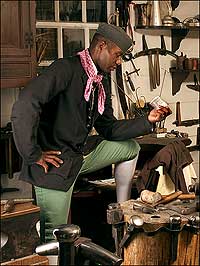

Interpreter Richard Josey portrays one of many slaves who escaped in cities, as notices for their return attest.

Northern slaves often worked in trades: interpreter Christine Lane as a seamstress; view an additional image of Christine Lane

Franklin, who owned and sold slaves, slowly came to appreciate the innate equality of all people. He theorized that the northern colonies expanded more rapidly because they had fewer slaves than the South. He said "slaves rather weaken than strengthen the state." He spoke of the "constant butchery of the human species by this pestilential detestable traffic in the bodies and souls of men."

Franklin's opinion derived from festering antipathy toward England and its slave trade, a philosophical movement that championed the rights of all human beings, and the Great Awakening and other religious upheavals.

Many Americans found in the slave trade a reason to despise their mother country. In 1774, Jay, a slave owner, said England was an "advocate for slavery and oppression." Slaveholder Jefferson wrote in a draft of the Declaration of Independence that George III's support of the slave trade was "a cruel war against human nature" and another justification for separation from England. Southern colonies, however, saw to it that the language was deleted. At the 1787 constitutional convention, Franklin favored a clause to ban the slave trade; when southern states objected, the ban was delayed for twenty years.

A consequence of opposing slave trading was opposition to slavery. It was becoming obvious that it was hypocritical of America to fault Great Britain for trafficking in slaves while oppressing people. "To contend for liberty and to deny that blessing to others involves an inconsistency not to be excused," Jay said. He was echoed by Massachusetts's Abigail Adams, who wrote in 1775 that it had "always appeared a most iniquitous scheme to me" to demand for ourselves "what we are daily robbing and plundering from those who have as good a right to freedom as we have." Such sentiments echoed the works of John Locke, Adam Smith, Montesquieu, and other Enlightenment philosophers, who taught that all humans had natural rights. Montesquieu said slavery not only degraded the enslaved but corrupted the enslavers. Smith, writing from an economic perspective, saw slavery as a hindrance to economic and individual progress.

Such views were mirrored in religious sentiments against slavery. Many Quakers who had been slaveholders in the first part of the 1700s shifted to abolition during the Revolution, enlarging an emancipation movement that had been percolating in the denomination for decades. John Woolman, a prominent member of the Society of Friends, said, "I believe slave-keeping to be a practice inconsistent with the Christian religion."

In Philadelphia at the start of the Revolution, Quakers founded the Society for Promoting Abolition of Slavery and Relief of Negroes Unlawfully Held in Bondage. Franklin would become its president in 1787. In Pennsylvania and New York, Quaker congregations began to expel slave owners. Methodists, on fire from the revivalist Great Awakening, came to see God's love and freedom as universals, and preachers set out to convert blacks. Methodists voted to remove slaveholders from church membership.

The antislavery influences of the Revolution, philosophy, and religion came together in Jay's 1780 remark that unless the new nation moved toward emancipation, its "prayers to Heaven for Liberty will be impious."

Something more earthly bolstered such prayers: the pressing need for troops to fight the enemy. "African Americans viewed the war as an opportunity to break the bonds of slavery," said Martin Blatt, chief of cultural resources at Boston National Historical Park. "It signaled the beginning of freedom."

Lord Dunmore, British governor of Virginia, offered freedom to enslaved men if their masters were in revolt against the crown and if they repaired to his standard. His proposal attracted hundreds of blacks.

At first, General Washington forbade the use of slaves in the American military because it would inflame southerners, ever fearful of slave uprisings. In 1779, Alexander Hamilton wrote to Jay, president of the Continental Congress, recommending the American ban be reversed. It was, and as many as 5,000 blacks—slave and free—served in the rebel army and navy. One observer wrote: "You never see a regiment in which there are not negroes."

When the war ended, the slaves who had fought on both sides expected freedom as their reward, a move that Hamilton had anticipated in his letter to Jay: "An essential part of the plan is to give them their freedom with their muskets."

New Hampshire slave Prince Whipple and others petitioned the legislature for freedom. They said that "justice, humanity, and the rights of mankind" demanded an end to slavery. It would be four years before New Hampshire acted, but Vermont moved quickly and freed its slaves in 1777. Soon, Pennsylvania, Massachusetts, Connecticut, and Rhode Island began gradual emancipation. By the 1790 census, there were no slaves to be counted in Maine, Massachusetts, and Vermont.

Full emancipation in the slaveholding northern states came in fits and starts. Connecticut, for example, considered emancipation bills in 1777, 1779, and 1780 before adopting a gradual emancipation law in 1784. In 1799, New York passed legislation that extended the emancipation process into the first quarter of the nineteenth century. "Nobody wanted to quit" slave owning, Berlin wrote. The "commitment to slavery ran very deep" among slave owners in the North, "even when it contradicted their ideology...Slavery was not a minor institution, and it took enormous energy and about fifty years to end it. It didn't go easily."

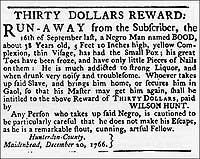

But some slaves did. Slaves in the North could walk away from their masters with relative ease. Because so many lived in urban areas, Berlin said, they could move around. "Fleeing slavery," said Shane White of the University of Sydney, "depended on having a free black population into which one could disappear. It was a lot easier in the north with New York, New Haven and Philadelphia than in South Carolina."

To some slaves, that mobility meant slipping out at night to a tavern or gambling den and coming home again. To others, it meant meeting with free blacks and sympathetic whites to lay plans for manumission. It could even mean hitting the open road. A window was an invitation to freedom, and many slaves took it. Berlin refers to an estimate that "between half and three-quarters of the young slave men in Philadelphia absconded from their owners during the 1780s." By just leaving in the night, slaves could melt into the North's large population of free blacks, seek refuge among Indian tribes, light out for Canada, or enlist as merchant seamen with the expectation that few questions would be asked on the waves.

Many blacks did something more than free themselves: they agitated for freedom for their peers. "Without the initiatives of free black and slaves," Berlin wrote, "they wouldn't have had emancipation." African Americans had allies in politicians, clergymen, and newspapers that a few decades earlier had advertised slave auctions and printed notices for the capture of runaways.

Among the slaves who spoke out for freedom was Phillis Wheatley. Bought as a child on Boston's docks, and given her first name from the ship that had carried her from Africa and her second from the family that owned her, Wheatley had gifts for learning and poetry. Her verse impressed Voltaire and Franklin, and led her to London to meet admirers. In 1774, two Boston newspapers printed a letter from her that included these lines: "In every human Breast, God has implanted a Principle, which we call Love of Freedom; it is impatient of Oppression, and pants for Deliverance."

Blacks also had the support of a slave who was content to remain in bondage because of his age. Jupiter Hammon, a Long Island slave, penned "An Address to the Negroes of the State of New-York" in the late 1780s. He quoted St. Paul's advice to slaves to obey their masters, not to steal from them, and to avoid profanity. But Hammon called liberty "a great thing, and worth seeking for." His pointed out how whites defended their liberty during the Revolution, and he asked: "How much money has been spent, and how many lives has been lost, to defend their liberty? I have hoped that God would open their eyes ...to think of the state of the poor blacks, and to pity us." Blacks could help that happen, he wrote, if they made sure "to lead quiet and peaceable lives in all Godliness and honesty," an example that would persuade whites that slaves could live on their own.

Such an example was given by Nero Hawley, a Connecticut slave who survived Valley Forge. When he gained his freedom in 1782, he returned to his home state, took up brickmaking, and collected his war pension. Nearing sixty, he died a veteran, a tradesman, and a free American of the North.

Prince Estabrook also went free. For fighting in the Revolution he won his liberty by 1790, and lived until 1830, dying at age ninety.

James Breig, an Albany, New York, editor and writer, contributed a story about eighteenth-century optics to the summer 2005 journal.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Ira Berlin, Many Thousands Gone: The First Two Centuries of Slavery in North America (Cambridge, MA, 1998).

- Martin Blatt and David Roediger, eds., The Meaning of Slavery in the North (New York, 1998).

- Leslie M. Harris, In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863 (Chicago, 2001).

- Peter Charles Hoffer, The Great New York Conspiracy of 1741: Slavery, Crime, and Colonial Law (Lawrence, KS, 2003).

- David Kobrin, The Black Minority in Early New York (Albany, 1971).

- Edgar J. McManus, A History of Negro Slavery in New York (Syracuse, NY, 2001).

- Shane White, Somewhat More Independent: The End of Slavery in New York City, 1770–1810 (Athens, GA, 1991).

- Henry Wiencek, An Imperfect God: George Washington, His Slaves, and the Creation of America (New York, 2003).

- Arthur Zilversmit, The First Emancipation: The Abolition of Slavery in the North

- www.slavenorth.com

- www.hudsonvalley.org/slavery

- www.pbs.org/wnet/slavery