Wheels and Riding Carts

text by Ed Crews

photos by Dave Doody

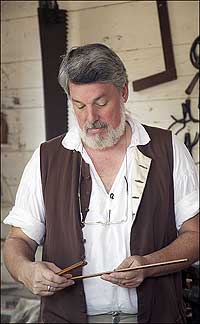

In the wheelwright's shop next to the Governor's Palace, from left, vehicle body specialist Chris Wright, master John Boag, and apprentice Paul Zelesnikar. The tools and skills are basic, but the work must be precise, "perfect enough," Boag says.

Boag works on a wheel spoke, which was usually made of oak. Wheels had to bear travel on unpaved roads and open fields.

"Making a piece of wood flat sounds easy, but actually it is tough to do," apprentice Zelesnikar says.

Phil Moore paints the riding chair that Wright built for Mount Vernon, which replicates the one built for Colonial Williamsburg and now in use. View additional photos of the riding chair.

Colonial Virginia's economy moved in a cart, the simple two-wheeled vehicle that was the pickup truck of the time. Everybody from the gentry to merchants used carts. Farmers especially depended on them.

"If you were a farmer in eighteenth-century Virginia, you couldn't operate without a vehicle. Around here, that vehicle was the cart. So wheelwrights had a wonderful customer base," said John Boag, master of Colonial Williamsburg's wheelwright shop.

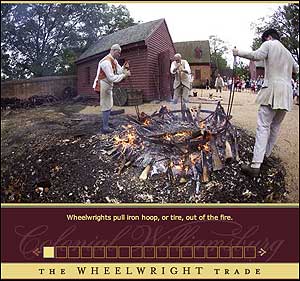

Given that almost everybody needed carts and thousands were in use, wheelwrights were as vital in their time as auto mechanics are in ours. They cut, shaped, and joined wood to make wheels that stood up to rough roads and rougher fields. Hub, spokes, and rim were wood. An iron tire usually circled the rim's exterior. Cart wheels were "dished," or bowed out, from the cart to reduce the strain on the wheels caused by the swaying gait of draft animals.

Wheelwrights also built and repaired carts. Cart design and construction were simple. Production required basically the same tools and techniques as did wheel making. Carts took two basic forms—those with stationary cargo beds, and dump carts. Dump carts worked like modern dump trucks. They had a bed that traveled in a horizontal position. By pulling a pin, the bed could be upended quickly and easily to empty a load. Carts varied by region and were built for local conditions.

Some wheelwrights also worked on wagons, common on the frontier, and produced wheelbarrows. They did not make coaches. But they sometimes worked with craftsmen who produced riding chairs. Boag and wheelwright's apprentice Paul Zelesnikar follow this practice today. They labor side-by-side with riding chair maker and vehicle body specialist Chris Wright in a shop at the Governor's Palace coach house in the Historic Area.

Riding chairs were popular in the 1700s, said Wright, a former furniture maker. These vehicles typically had two wheels and seated one or two people.

"Riding chairs were more comfortable than riding on a horse," Wright said. "In a riding chair, you could move a bit, shift your weight. You didn't have to sit on the back of a sweaty horse in August." Also, it was easier on the horse, which didn't have the weight of a human on its back.

Like furniture making and the wheelwright's trade, Wright's craft requires woodworking skills and a knowledge of wood, its limitations and its potential. Wright said that joinery skills were important for making riding chairs that were comfortable, strong, and reliable. Wright is a self-taught riding chair maker. Nobody teaches the craft today. He has developed the skill as a historical detective, deducing vehicle construction by examining surviving examples.

The wheelwright's shop is large, airy, and bright. Shavings litter the floor. Hanging on the walls are saws, clamps, files, chisels, and patterns for felloes, the curved portions of a wheel rim. A drawing of a wheel is scribed on a wall as a construction aid. A giant wheel with a hand crank sits along a rear wall. It's used to power a lathe.

Boag, Wright, and Zelesnikar operate the site as a small urban establishment, meeting the needs of a varied clientele. It was a typical American arrangement. Only American and English cities like Philadelphia and London could support big firms with highly specialized workers.

Like all crafts, the wheelwright's was learned through an apprenticeship. During this training, a young man would pick up basic math and develop an eye for shaping wood flat or round. Apprentice Zelesnikar said, "The hardest thing for me is planing. Making a piece of wood flat sounds easy, but actually it is tough to do. You'd expect that you could make something flat. But what you see as flat isn't necessarily really flat. You need to develop a feeling for when you achieve this. You really need to retune your senses."

Craftsman also needed woodworking abilities. Perhaps the most important was the ability to do quality mortise-and-tenon work. This involved cutting a cavity—a mortise—in one piece of wood and shaping another component—a tenon—to fit snugly in the cavity. That's how spokes are secured in the hub and the rim.

With these skills, an apprentice learned to make a wheel. Production was straightforward. Workers prepared the wood, then fashioned parts. Spokes typically were made of oak, felloes of ash, and hubs of elm. Elm made strong hubs because its grains ran horizontally and vertically. Once made, parts were assembled into a wheel.

The key to a reliable wheel was the hub. Its face had to be absolutely flat so that wheel makers could bolt them securely in place for completion. Cutting the holes in hubs for the spoke also was challenging.

"I concentrate most with apprentices on the hub," Boag said. "Mortising the hub is the hardest task. The job is to learn what is perfect enough. The work has to be precise. No matter how perfectly I try to make a hub, not all the spokes ever seem to fit perfectly."

Although the wheelwrights in Williamsburg demonstrate and explain the craft carefully, visitors often are puzzled by their work.

"We have one of the hardest trades to explain," Zelesnikar said. "Our trade is so foreign to visitors because nobody does anything like this today. Often, the basic concepts are tough to grasp."

But Boag, who has twenty years of experience, said, "You don't have to be a rocket scientist to do this. You have to learn to be a sound craftsman. The chief thing an apprentice needed to do was to pay attention to the master."

Ed Crews contributed to the summer 2004 journal a story on Revolutionary War intelligence.