Hunting for a Little Ladle

Tobacco Pipes

by Ivor Noël Hume

The author holds a long clay "churchwarden" pipe, which is among the most fragile of eighteenth-century artifacts.

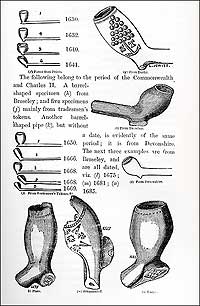

Antiquaries of the 1860s attempted to date clay pipe bowls by their evolving shapes and sizes. Few makers included dates in their marks, however.

The author found this 1683 pipe in the River Thames. Makers often stamped their initials, though seldom on the bowl.

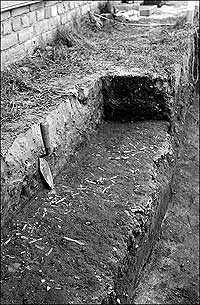

An unexpected use for broken pipes. More than 11,000 fragments were made use of in this ca. 1740 walkway beside Colonial Williamsburg's George Reid House on Duke of Gloucester Street.

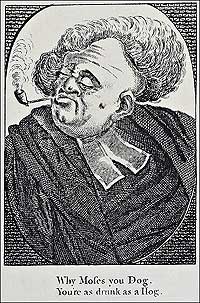

Wig akimbo, a cleric is in his cups in this ca. 1795 woodcut. On such occasions, a shorter pipe stem made for easier handling.

The late Audrey Noël Hume had to measure the size of the hole through every one of the stem fragments from the George Reid House walkway.

In 1992, while searching for Sir Walter Ralegh's Lost Colony on Roanoke Island, North Carolina, excavators found fragments of aboriginal pipes smoked there by colonists in 1585 and 1586. From this small beginning the taste for "drinking tobacco" was born.

A jumble of seventeenth- and eighteenth-century pipes. Though identical to others excavated at Jamestown and Williamsburg, these were found in London.

Archaeologist Al Luckenbach, director of Maryland's Lost Towns Project, shows the author pipes and equipment found on a 1660s pipe maker's kiln site in Anne Arundel County. His is the most important contribution made to the history of colonial American pipe making.

In the eighteenth century, smoked pipes were sanitized in iron cradles called kilns and baked in ovens.

The stems of these English pipes from ca. 1690-1720 measure 11". The Dutch tobacco box is of the same period.

The pipe, so

lily-like and weak,

Does thus thy mortal

soul bespeak.

– Rev. Ralph Erskine, Gospel

Sonnets (ca. 1733)

Throughout Virginia's colonial centuries, tobacco was the economic lifeblood of the Old Dominion, and unless one rolled it to smoke as a cigar, or took it as snuff, a pipe was as necessary to its consumption as fire. Pipes are known in silver, brass, pewter, iron, and even lead, but clay was the primary material and so remained until the end of the nineteenth century. The clay pipes' fragility ensured that they were broken almost as fast as they were made, and fragments are strewn across every Virginia colonial home site. But just as few of us give much thought to what later generations might deduce from our discarded bottle caps, no one in the eighteenth century considered how a twenty-first-century archaeologist might use his broken pipe as a clue to his life and time. Especially time. The characteristics of tobacco pipes changed with the years, and if an archaeologist can date those changes, so can he date the objects with which they are are found.

There are thousands of pipe fragments found in Williamsburg. An early explanation for their ubiquity had it that in colonial-era taverns pipes passed from mouth to mouth, but that in the interests of hygiene the previously lip-gripped section was broken off and thrown away. There is no documentary support for that notion, but it is known that used pipes were placed in iron cradles and heat cleansed in bake ovens before being issued to the next round of smokers.

The real explanation for the ubiquitous pipe-stem fragments is more prosaic: they were easily broken. If you drop a typical seventeenth-century eleven-inch clay pipe - something that curators try to avoid - its stem is likely to fracture into six or seven pieces, and when you do the same for a long "churchwarden" pipe from the end of the eighteenth century, the fragments may run to as many as twenty. That all these little pieces might have something to say to archaeologists was first recognized in the mid-twentieth century when the National Park Service's archaeologist at Jamestown, Virginia, Jean Carl "Pinky" Harrington started studying not the stem fragments per se but the sizes of the holes through them.

By itself, this sounds like a lunatic occupation, and at the outset critics were quick to say so. Interest in the history of the evolution of the clay pipe's bowl, however, goes back a deal further and was the subject of scholarly interest as early as 1863. In that year a clergyman named Hume, no relation to me, began an essay on the topic by saying that "very small pipes are found all over these islands, which are known in Ireland as Fairy pipes or Danes' pipes." The pragmatic cleric was quick to add that "the Irish attribute any thing unusually small to the fairies, and anything very ancient or inexplicable to the Danes." Nevertheless, it was true that the most ancient of pipes were, indeed, very small. The question, of course, was how ancient?

Conventional wisdom - at least that to be found in the pages of the Encyclopaedia Britannica - credits the introduction of the tobacco pipe to Europe to "Ralph Lane, first governor of Virginia, who in 1586 brought an Indian pipe to Sir Walter Raleigh and taught the courtier how to use it." The Reverend Hume thought so, too, asserting that the use of American tobacco began in England around 1585. If one wishes to narrow the source down to a few square yards, it is to be found at the National Park Service's Fort Ralegh on North Carolina's Roanoke Island. On that site we found fragments of Indian tobacco pipes smoked by the colonists who were there in 1585 and 1586.

Among them was Sir Walter Ralegh's protege, Thomas Harriot, who on his return to England, wrote:

We ourselves during the time were there used to suck it after their maner, as also since our returne, & have found maine rare and wonderful experiments of the vertues thereof ...the use of it by so maine of late, men & women of great calling as else, and some learned Phisitions also, is sufficient witnes.

Harriot described the Indians' practice of "sucking it through pipes made of claie into their stomacke and heade; from which it purges superfluous steame & other grosse humors."

Like so much else in historical lore, the encyclopedia and the Reverend Hume were wrong. The Spaniards had known of the alleged benefits of tobacco smoking for close on a hundred years, having discovered its use from the conquered Indians of Central America. It was also known to the French in Florida long before Ralph Lane built his fort on Roanoke Island. Reporting on Sir John Hawkins's voyage to the West Indies in 1565, chronicler John Sparke wrote:

The Floridians when they travell, have a kind of herbe dried, who with a cane and an earthen cup in the end, with fire, and the dried herbs put together, doe sucke thorow the cane the smoke thereof, which smoke satisfieth their hunger, and therewith they live foure or five dayes without meat or drinke, and this all the Frenchmen used for this purpose.

Whether it was Hawkins and not Ralegh who introduced pipe smoking to England or some passing Frenchman, there is no doubt that eight years after Hawkins's voyage, "taking in the smoke of the Indian herb called tobacco by an instrument formed like a little ladle . . . is greatly taken up and used in England." So here we have two descriptions of tobacco pipes that precede the Roanoke voyages, the first a cup attached to a cane, and the second shaped like a little ladle.

The first reference is to something resembling the typical American pipe of the nineteenth century, one that had come to North Carolina with Germanic immigrants in the middle of the previous century. At that time Moravian potters at Bethabara were making clay pipe bowls in designs that included the feather-capped human heads that might or might not have been intended to resemble Indians. An example of this cane-and-clay style in my collection is amusingly anachronistic, having been made as a souvenir of the Jamestown Exposition in 1907, its bowl shaped to resemble the island's ruined church tower. No such combination was used at the settlement in the seventeenth century.

By the time the first colonists landed at Jamestown, the English already had thirty years in which to develop their own tobacco pipe technology. A disapproving German visiting in 1598 noted that the "English are constantly smoking tobacco adding that they have pipes on purpose made of clay." No archaeologist has found such a pipe in a context that can be dated with any certainty prior to about 1600. A pipe found on the foreshore of the River Thames at London may be as close as we can yet come to 1573's little ladle. Unfortunately, it does not follow that tiny pipe bowls fit for fairies are necessarily older than others that are larger. The smallest yet found in Virginia were discovered in a context of 1622 beside the River James at Martin's Hundred, near Williamsburg.

Nineteenth-century interest in the age of pipes and their shapes was purely antiquarian. No one thought that they might be of use to archaeologists. In truth, Victorian-era archaeologists had no interest in anything from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Nevertheless, antiquaries like the Reverend Hume picked up pipe bowls in their gardens and wondered how old they were and why they differed in shape.

Finding any answer, not necessarily the answer, wasn't easy. Unlike the seventeenth-century Dutch, whose artists painted virtually every aspect of contemporary life - including smokers - British artists found their markets as portrait painters, none of whose sitters posed smoking. But there were minute pictures of tobacco pipes stamped onto tobacconists' trade tokens. In most instances these emblems were miniature versions of the signs hanging over the doors of their establishments. Thus, for example, in the village of Eton in 1666, tobacconist Richard Robinson issued a token showing his sign depicting two pipes crossed. Someone, perhaps it was the Reverend Hume, came up with the idea of drawing all the more than forty pipes so depicted. But, as an illustration from the reverend's book reveals, the exercise got him nowhere. Copies from earlier seventeenth-century engravings and woodcuts were no more informative. Pipes were an accessory, and as long as they were shown having a stem with some sort of bowl on the end, the viewer got the idea.

Although the guild of tobacco pipe makers had been established in London as early as 1619, prompting makers to identify their products by inscribing their marks or initials on the bases of bowls, very few of them supplied a date. Most of those that did came from the pipe-making center at Brosley in Shropshire and were stamped with dates in the last quarter of the seventeenth century. As the bowls on which dates appeared varied in shape, and as the dates probably referred to the maker's acceptance into his guild and not to the pipes on which they appeared, all this evidence was as confusing as it was helpful.

More than eighty years would slip by before anyone else in England began to take an interest in clay pipes, and this time the clues were archaeological. From the slowly accumulated silting of the great ditch around the medieval city of London, which had been uncovered thanks to Hitler's bombing, came large numbers of seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century pipes. The then curator - they called him keeper - of the City's Guildhall Museum, Adrian Oswald, was the pioneer of postmedieval archaeology in England, and it was he who began to create a chronology of shapes on the basis of their location in the ground - those in the upper levels of the ditch being less old than those deeper down. If that sounds obvious, it is. All archaeological reasoning is firmly seated in common sense and is not nearly as abstruse as some practitioners might want you to believe.

Oswald published his landmark findings in 1948, and immediately curators and archaeologists began to use his chronology. Quite independently, however, at Jamestown, where serious excavations had begun in 1933, National Park Service archaeologists were digging up pipes of many shapes and sizes and wondering what to make of them. One of the ponderers was anthropologist J. Somerfield Day, who seems to have been the first to suggest "that the wide range of pipe bowl shapes unearthed" at Jamestown "might provide an evolutionary series that could be used to distinguish different depositional dates." He was right.

Day's successor at Jamestown, Harrington, began by publishing an evolutionary series of shapes akin to Oswald's, but he went further and began his sequencing by measuring the bores of the stem holes - big holes being early when the stems were short and decreasing in diameter as they were made longer and thinner. From that day onward, no self-respecting historical archaeologist has sallied forth without having at his disposal a set of wood drills graduated in sixty-fourths of an inch by which to measure the holes.

Harrington presented his sequencing in an easy-to-use chart showing the relative percentages of stem-hole sizes in five steps through the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. That was in 1954. Almost immediately, Harrington's chart became the key to the grail. But how reliable was it?

As invariably happens, a mathematician, or nowadays a computer nerd, comes along to turn general trends into programmable numbers. In 1962, scholar Lewis Binford did just that, converting Harrington's modest progression into a mathematical formula that provided a mean or central deposition date for each assemblage of stem fragments. Nobody asked whether a mean date was really useful. But hailing it is as the DNA of historical archaeology, everyone used the formula - perhaps fearing that its neglect would be construed as not being on the cutting edge of the profession.

A year later, during Williamsburg excavations beside the Duke of Gloucester Street house occupied in the mid-eighteenth century by blacksmith Hugh Orr, today known as the George Reid House, we found a pathway paved with more than eleven thousand broken tobacco pipe fragments. Whether they represented a shipment that arrived shattered from England or had been discarded for some other reason, we never found out. But it was evident that they were related in time and origin, for many bore the same makers' marks. The late Audrey Noël Hume, in her role as archaeological curator, put the Binford formula through extensive testing and found that to arrive at a consistent mean date required more than 1,000 fragments, a number much larger than is usually found together on a colonial site. In this case, however, 1,100 were sufficient to arrive at a consistent mean date of 1740, which was probably about right for that context.

Thirteen years later, during excavations at Martin's Hundred, the Binford formula got another body blow. Pipes from a single pit, all probably deposited at about the same time, gave Binford dates of 1619 and 1617 down to the lowest level at 1616. This would have been joyous news had not all the pipes been sitting on top of a slipware dish dated 1631.

With the pipe stem holes and bowl shapes analyzed to a fare-thee-well, one detail remained unquantified, namely the interior diameters of the bowls, which evidently were made larger as tobacco became cheaper. I resolved to base a new and all-revealing study of bowl mouths on examples recovered from tightly dated shipwrecks, mostly from Bermuda. The initial results were sufficiently encouraging to merit rehearsing the word Eureka! while shaving. But when I added much larger samplings from the no-less tightly dated Great Fire of London in 1666, my thesis turned to ashes.

Since Day, Harrington, and Oswald did their pioneering studies, more ink has been devoted to the dating of tobacco pipes than any other artifact category. A study of Bristol pipes alone ran to five thick volumes. The rolls of pipe makers' apprenticeships, bills, inventories, church and court records, have been scoured to try to equate the names with initials on the pipes. Colonial Williamsburg's report on Martin's Hundred devoted forty-five pages to pipes and tried to separate one type from another, one date from another, and one manufacturing source from another - all the time blissfully unaware that buried beside a Maryland creek lay definitive answers to several of the questions.

In 1991, archaeologist Al Luckenbach discovered Emmanuel Drew's pipe-making factory site, active from 1661 to 1668, when a bulldozer scored the edge of a small hill and exposed artifacts that included a lump of burnt clay with fragments of tobacco pipe stems built into it. Drew's 1668 inventory listed "a payre of Brass Pype Moyldes" - the two-part molds used in shaping clay tobacco pipes.

There for the first time Luckenbach was seeing the scope of pipe-making designs and skills in a well-documented American context. The oldest tightly dated pipe-making site yet discovered, its fragments of kiln furniture, varieties of clays, and examples of the pipes themselves make this discovery of monumental importance to archaeologists on both sides of the Atlantic.

It also makes nonsense of many conclusions hitherto reached about the nationality or racial origins of contemporary pipe makers working in Virginia. Types that had been thought to be English made, weren't, and others believed to have been made only in Virginia were coming from Maryland.

Luckenbach's revelation made it crystal clear that an enormous amount has still to be learned about the history of tobacco pipes, and doubtless many more volumes to be published - none of them, one suspects, likely to make popular bedtime reading save as a substitute for counting sheep.

Williamsburg-based Ivor Noël Hume contributed to the winter 2002-2003 journal a story on Sir Francis Bacon.