Colonial Dress Codes

by Linda Baumgarten

From left, interpreters Brooke Barrows, Stewart Pittman, Preston Jones, Cathy Hellier, Diana Freedman, Rick Hill, and Conrad Mann in the old-fashioned but prescribed formal dress of hoop skirts and knee breeches.

Early nineteenth-century doll of a liveried servant. The fineness of material and excess of buttons reflected the position and affluence of the master.

Tightly buckled at the knees, Conrad Mann's breeches billow in the seat to permit comfortable sitting. Preston Jones assists with the waistcoat as the gentleman readies himself for a ball.

Slaves mended, patched, and embellished their clothing to create an individual style. Interpreters Bridgette Houston and Richard Josey in the Rural Trades yard.

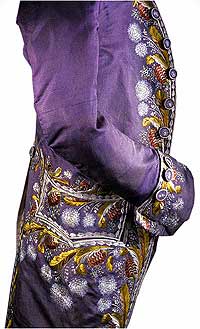

A man of high stature and considerable resources could command the embroidered flourish of this dress suit.

The hooped gown style, with ruffled sleeves and petticoat underneath, grew bigger, then smaller, before vanishing in the nineteenth century.

In 1774, Norfolk, Virginia's residents staged a ball for Governor Dunmore and his wife, Charlotte, who had arrived in the colony to join him. It was splendid. Everyone dressed in the finest clothing. British navy officers powdered their hair as white as could be. A gentleman in attendance said one Colonel Moseley, wearing "his famous wig and shining buckles," led Lady Dunmore in the minuet, and she went

sailing about the room in her great, fine, hoop-petticoat, (her new fashioned air balloon as I called it) and Col Moseley after her, wig and all...Bless her heart, how cleverly she managed her hoop, now this way, now that, every body was delighted. Indeed, we all agreed that she was a lady sure enough, and that we had never seen dancing before.

During the same year, five Virginians joined scores of others who took to the road to find freedom from slavery or servitude. In July, a twenty-two- or twenty-three-year-old personal servant named Harry ran away from his master. Hoping that someone would spot and return him, Theodorick Bland took an advertisement in the Virginia Gazette. Bland knew that clothing was an important identifier, and included a description of Harry's garments, along with physical characteristics. Harry stood five feet ten or eleven inches, had scars on his arms and back, and "remarkable high Insteps," which was perhaps the reason he could not "bear to go barefoot." Harry was "very fond of dress," and ran away wearing a full suit of clothing: dark brown livery coat "turned up with Green," a waistcoat to match, striped breeches made of the cotton velvet textile velveret, a white shirt, shoes, and stockings. Bland said Harry probably had other clothes with him.

Thirty-year-old Tom and his wife, Fanny, also ran away from slavery. They left Charlotte County and were probably headed for Gloucester County, where they had lived before. According to the April 14, 1774, issue of the Gazette, Tom had on an "old Virginia Cloth Jacket and Breeches, which are probably wore out by this Time." Fanny, too, wore a two-piece suit, a blue woman's fitted jacket and a petticoat, or skirt, which was "very much patched."

About a month later, John Jones and Elizabeth Lewellin escaped from servitude in Botetourt County. John was a thirty-six-year-old sailor and shoemaker. Born in Liverpool, England, he came to Virginia as a convict servant who was required to work off his sentence. According to the May 26, 1774, Gazette, the five-foot-eight-inch-tall man had brown hair, a large nose, smallpox scars, round shoulders, and a stooping walk. Besides what he had on, John had a change of clothing. In all, he had a sailor's jacket, breeches made of the sturdy wool fabric Fearnought, two shirts of linen woven in Virginia, a pair of trousers, and enough coarse linen Osnaburgs to make another pair. Patrick Lockhart, who placed the advertisement, suspected John also had a stolen pair of new buckskin breeches.

Lewellin was a twenty-five-year-old black-haired Welsh woman who stood about five feet six inches tall. Smart, active, capable, she could read and write. She also had changes of clothing, among them a new calico gown, the period word for a dress, styled so that it buttoned in the front. She owned petticoats, one made of the fine black wool calimanco, an old green pair of stays, a corset, a striped garment called a "bed gown," and "sundry other Clothes."

There were similar scenes throughout the colonies: some people attended balls dressed in the finest silks, while others went about their daily business, labored in the home or fields, or ran off in search of opportunity. Their clothing was as diverse as they were. Yet few were entirely free to choose their own clothing styles. Everyone was caught up in the dress codes created by fashion, social expectations, occupational necessities, status, and economics. It is relatively easy to document what was worn in the English colonies, gowns, petticoats, stays, suits, jackets, breeches, trousers, but less easy to understand what the clothing says about the people and their aspirations. How do we translate the evidence from written records such as those drawn on above?

Let us return to the ball in Norfolk. One of the garments sounds somewhat out of date for the mid 1770s. Although the wide-hooped skirt, such as Lady Dunmore's, had been the rage in the 1740s, the style had been supplanted by smaller hoops, and eventually by skirts with no hoops. Lady Dunmore, the daughter of an earl and a countess by marriage, must have known the rules of proper dress. Indeed, she did: the ball was a formal occasion, where the rules of daytime fashions were suspended in favor of time-honored styles and conservative fashions. The gown was not described in detail, but it certainly followed the prescribed fashion for formal attire. It would have been made of the finest silk, the low-cut bodice fitted carefully over a heavily boned corset undergarment. Like most formal gowns, the sleeves certainly had multiple ruffles cascading over the elbows. The attached skirt, constructed of yards of fabric extending out at the sides, was probably open at the front to show off another skirt underneath, this one called a petticoat, and likely trimmed to match the outer gown.

Gowns with wide hoops were required at formal evening occasions and at the British court until well into the nineteenth century. Lady Dunmore's outfit acknowledged the formality of the occasion and demonstrated her aristocratic origins. The graceful way she walked and danced in the unwieldy hoops confirmed her status.

Men also adhered to a subtle dress code for formal events. Men who sported stylish but plain wool coats and pants for everyday wear changed into powdered wigs and conservative suits with buckled knee breeches for formal events. The suit Colonel Moseley wore was probably made of shimmering silk, perhaps embroidered with a floral design. His suit coat would have had pleated skirts that reached his knees, worn over a matching waistcoat, or vest, and knee-length breeches. Because they were buckled tightly beneath his kneecaps, the colonel's breeches would have been cut with extra fullness at the seat to allow him to sit and move about with ease, avoiding the danger that his pants might slip dangerously low on his hips. He would have worn long stockings made of knitted silk or fine linen thread, gartered above his knees.

At first reading, the runaway household servant Harry appeared to have a rather elegant suit, too, "a dark brown Cloth Livery Coat turned up with Green, Waistcoat of the same, striped Velveret Breeches." Livery suits looked elaborate, but they signaled submission. The services of the liveried man belonged to his employer, and the fancy suit enhanced the employer's status, not that of the servant wearing the clothing. It was important that Harry's occupation and status be obvious. To accomplish that, livery suits followed a stylistic formula recognized by the cognoscenti. Livery suits typically had a contrasting color on the cuffs and collar, "turned up with Green", and usually were embellished with special braid trimmings and buttons. Harry probably abandoned the distinctive and recognizable suit he was wearing when he left.

Runaway slaves Tom and Fanny apparently had fewer apparel options. Tom's clothing was practical and inexpensive. He wore a jacket and breeches of Virginia fabric. It is possible that Tom, Fanny, or one of the other slaves on the plantation had spun and woven the cloth. Not for him a three-piece suit with a full-skirted coat that would have interfered with movement. Tom's jacket gave him the freedom of movement required by a laborer, and required less fabric.

Fanny's clothing was functional and basic, too. The jacket-and-petticoat ensemble is the most commonly recorded clothing of African-American women. Although Fanny may not have owned a corset, her jacket, which probably laced closely at the front, would have given her figure support. Her petticoat, or skirt, was "very much patched."

Plantation records show that most slaveholders provided their agricultural laborers with a minimum of clothing, issued at the beginning of summer and winter. By the end of each season, the clothing must have been threadbare. Throughout most of the eighteenth century, planters typically ordered hundreds of yards of inexpensive woolens and linens from England for slaves' suits, shirts, and shifts. With the approach of hostilities with England in the late 1760s and early 1770s, increasing numbers of planters turned to producing their own linen, cotton, or woolen "Virginia cloth" to lessen or eliminate their dependence on Great Britain. The economics of buying or producing textiles in bulk, not to mention the planters' expectations of what slaves should wear, appeared to leave little room for individuality. Some runaway advertisements say groups of slaves were "all dressed alike" or wearing "the common dress of field slaves." Yet a careful reading of period sources shows that slaves not only desired individualized clothing but most managed to achieve it, to exert a measure of control over their appearance. Scholarship has shown that slaves enhanced their appearance and expressed personality by such techniques as styling the hair, wearing a large kerchief as a head wrap, dyeing clothing, purchasing or trading for pieces of clothing, wearing garments in new combinations, or adding pockets or patches. Was Fanny's petticoat "very much patched" because it was worn, or had she, perhaps, deliberately added decorative patches? The possibility is that what a white slaveholder viewed as a profusion of mending patches was, in the eyes of the woman who wore the petticoat, a purposeful assemblage of aesthetically pleasing color and pattern on an otherwise plain garment.

Convict servants John Jones and Elizabeth Lewellin had a choice of styles among the garments they took. According to the advertisement, she had apparently brought "a Sum of Money" with her when she came to Virginia. Elizabeth had a new gown of calico, a fashionable cotton textile often printed in floral patterns. Originally imported from India at great cost, calicos were imitated by European printers, who produced versions affordable to workingwomen who wanted a fashionable look on a budget. Lewellin's gown was made with buttons at the front of the bodice, a style that came in during the 1760s. She also had the more casual bed gown. Despite the name, bed gowns were for every day and for work. The loose, three-quarter-length sleeved garment would have been paired with a petticoat to make a comfortable ensemble that gave freedom of movement and comfort, with or without a corset underneath. Elizabeth's clothing gave her flexibility as she mixed and matched the petticoats with the two styles of gowns, and she had individualized outfits for occasions ranging from relatively dressy to work.

Jones's clothes reflected his former occupation as a seaman. His sailor's jacket probably resembled those shown in period prints, collarless, button-front garments that ended below the waist at about mid-thigh. Typically, the long sleeves had buttoned plackets at the wrists instead of cuffs. Long skirts found on dressier suit coats would have been impractical for a seaman. Many sailors, as well as other workingmen, wore pants called trousers, fashioned without the tight bands below the knees. Usually made of coarse, washable unbleached linen, some looked like knee breeches without the band, and others extended to the calves or ankles. Some had wide, full legs, a style called "petticoat trousers." Jones could vary the appearance and functionality of his clothing, and perhaps hide his status as a convict servant, by changing from his trousers into the warm wool Fearnought breeches or the buckskin leathers he appears to have stolen. Like other men described in period sources, he may have pulled the trousers on over the top of his breeches to protect the more expensive breeches fabric from soiling or abrasion. For Jones and his companion, more clothing meant more options.

The story of colonial clothing is the story of people who used apparel for more than modesty or protection from the elements. They selected clothing and accessories to announce status, wealth, occupation, and personality, all within the constraining limits of the time and place. Sometimes the message was evident through the form of the garment, a hoop petticoat or a sailor's jacket, for example. More often, people relied on the nuances of fabric, tailoring, trimmings, accessories, or the accumulation of styles to speak silently on their behalf.

Click on each man to view details.

Linda Baumgarten, Colonial Williamsburg curator of textiles and costumes, curates The Language of Clothing exhibition. Baumgarten's catalog, What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America, won the 2003 Millia Davenport award from the Costume Society of America.

Suggestions for further reading:

Linda Baumgarten, Eighteenth-Century Clothing at Williamsburg (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1986, reprt. 2002).

What Clothes Reveal: The Language of Clothing in Colonial and Federal America (Colonial Williamsburg Foundation in association with Yale University Press, 2002).

Thomas Costa, comp., "Runaway Slave Advertisements from 18th-century Virginia Newspapers." http://etext.lib.virginia. edu/subjects/runaways/.

Shane White and Graham White, Stylin': African American Expressive Culture (Cornell University Press, 1998).

Lathan Windley, comp., Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History from the 1730s to 1790. Vol. 1: Virginia and North Carolina (Greenwood Press, 1983).