Out, “Damn’d Proverbs”

Eighteenth-century axioms, maxims, and bywords

by James Breig

Chapter 1 of Proverbs,

as it appears in a 1723 Bible

printed at Oxford

by John Baskett

Like many an author before him and after, when Robert Munford, a member of the Virginia House of Burgesses, turned his pen to playwriting, he wrote about what he loved: politics. And he suggested what he didn’t love. In Munford’s The Candidates, a farce about an Old Dominion election campaign, a character snaps: “Don’t preach your damn’d proverbs here.”

Others shared that opinion of proverbs, but many more ordered their lives according to them—or according to The Proverbs, the twentieth book of the Old Testament. In the eighteenth century, the King James Bible, completed in 1611, was found on a polished desk in the stately Wythe House on Williamsburg’s Palace Green. It might also have lain on a hand-hewn bench in the shakiest shack in the Virginia wilds. It was certainly in the pockets of itinerant preachers. Thus, in the morning as they rose, or in the evening as they rested, wealthy lawyer George Wythe, the poor backwoods farm wife, and the traveling man of God might turn to the Good Book to read “A soft answer turneth away wrath: but grievous words stir up anger,” and “He that spareth his rod hateth his son: but he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes.”

Axioms—read in the Bible, quoted from classical literature, and handed down through families—were a part of everyday life in 1700s America. Politicians, merchants, plantation owners, tavern keepers, womenfolk, and slaves used pithy and sage sayings to make a point, admonish a child, or share an experience. Among the main sources for them was “The proverbs of Solomon the son of David, king of Israel,” a thirty-one-chapter collection of maxims. In its very first lines, it elucidates the rewards of learning its sayings:

1:2 To know wisdom and instruction; to perceive the words of understanding;

1:3 To receive the instruction of wisdom, justice, and judgment, and equity;

1:4 To give subtilty to the simple, to the young man knowledge and discretion.

1:5 A wise man will hear, and will increase learning; and a man of understanding shall attain unto wise counsels:

1:6 To understand a proverb, and the interpretation; the words of the wise, and their dark sayings.

Most proverbs have been handed down from the misty realms of the past, as if they dropped from the lips of Adam or Eve. In 1716, Robert South, a celebrated Anglican preacher, defined a proverb as “the experience and observation of several ages, gathered and summed up into one expression.”

Linda and Roger Flavell, the authors of Dictionary of Proverbs and Their Origins, said in an email from their home in England that proverbs are a good illustration of how expressions seem to arise from nowhere—and everywhere: “They are by definition the wisdom of the people, and they are passed down from generation to generation in oral communication. We do have some very old records (the Bible’s Book of Proverbs has entries going back 3,000 years), but even they rarely tell us who coined the expression in the first place. Many are attributed to Solomon, but he was probably the collator and not originator of the majority.”

Antoinette Brennan, as teacher Ann Wager, weaves biblical proverbs into lessons for Ciara Montgomery, left, Milleta Kotova-Cooper, and Ryan-Kristoff Canaday.

A difficulty in nailing down who created a dictum, the Flavells say, is that “most expressions—certainly and obviously before widespread literacy—originated in speech. Who is to know whether an eighteenth-century writer coined an expression in his work, or simply wrote down what he heard, or reshaped in more memorable form a phrase in his community? We know little about this, as hardly any writers comment on the genesis of their neologisms.”

Understanding ancient axioms can pose a problem for modern readers because the meanings and usage of words subtly shift and shade in the course of time. As a result, “The meaning of old expressions, at first sight, can seriously mislead,” the Flavells said. An example is “put one’s nose to the grindstone,” which modern people use as a simile for working hard, often by choice. But the expression, which has been around at least since the sixteenth century, originally meant to treat someone cruelly, an action that was against his will. As the 1952 preface of the Revised Standard Version of the Bible says, a major reason for revision of the King James Version “is the change since 1611 in English usage. . . . The greatest problem, however, is presented by the English phrases which are still in constant use but now convey a different meaning from that which they had in 1611.”

English maxims have been enriched by other languages—French, Italian, and Spanish, for example. In 1778, the Pennsylvania Gazette reported: “He who lives in a glass house, says the Spanish proverb, should never begin throwing stones.” A 1786 essay refers to an early, non-English form of the familiar saying “Fool me once, shame on you; fool me twice, shame on me.” Wrote George Horne, an English divine: “When a man deceives me once, says the Italian proverb, it is his fault; when twice, it is mine.”

The Flavells said: “Linguistic borrowing is widespread and age-old,” but “sometimes, it is difficult to know whether borrowing is the source or some common universal theme.” Cooking, eating, farming, and the weather are topics that give rise to similar locutions in dissimilar locations. Thus, variations of the common proverb “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush” can be found in Romanian, Italian, Portuguese, Spanish, German, and Icelandic. It began in medieval Latin.

In the eighteenth century, the word “proverb” had meanings besides a concise expression of received truth. It was used, says the Oxford English Dictionary, to mean “a common word or phrase of contempt or reproach.” Lexicographer Samuel Johnson is quoted by James Boswell as saying that an acquaintance “should take care not to be made a proverb.” The word could also mean “a matter of common talk” and “an allegory.” In addition, it had a complimentary sense that implied that someone was the apotheosis of a specific virtue. For instance, the Virginia Gazette’s account of the death of Sir John Randolph in 1737 mentions his great-uncle, Sir Thomas Randolph, who served Queen Elizabeth “in several important Embassies.” The queen, said the Gazette, was “happy, even to a Proverb, in the Choice of her Ministers.”

But its common and still-current meaning was the one which Benjamin Franklin employed for twenty-five years in Poor Richard’s Almanack. That made him, along with everything else he was, a paroemiologist. That word, coined in the late eighteenth century, means an expert in proverbs and derives from the word “paroemia,” which means byword. A modern paroemiologist says Franklin coined about 5 percent of the sayings in his Almanack; he collected the remainder, sometimes reworking them, from other sources. The newspaper Franklin made famous, The Pennsylvania Gazette, salts its issues with such maxims as “Many hands make light work,” “A penny saved is two-pence clear,” Honesty is the best policy,” and “Kill two birds with one stone.”

The importance of proverbs, then and now, is indicated by the existence of paroemiologists and by websites dedicated to the study of aphorisms. One such site, www.deproverbio.com, is packed with scholarly information and articles, including a ranking of the popularity of proverbs based on how often they appear in print. “First come, first served” comes out on top, followed by “Forgive and forget,” “Money talks,” and “First things first.” Such examples demonstrate one of the hallmarks of a proverb: succinctness. Noah Webster called brevity “the great value of proverbs and maxims . . . many of which contain important truth in a nutshell.”

Another hallmark of a proverb is its commonality. The Oxford English Dictionary defines a proverb as “a short, pithy saying in common use,” a definition that rules out lengthy quotations. Some axioms that were in frequent use in the eighteenth century are heard 300 years later. “Look before you leap” dates from 1694, for example, and Samuel Adams, John Adams, and Thomas Jefferson all referred to the danger of having “many irons in the fire.”

Interpreter B. J. Pryor leavens a sermon from the Bruton Parish pulpit with a few homely proverbs from the Bible.

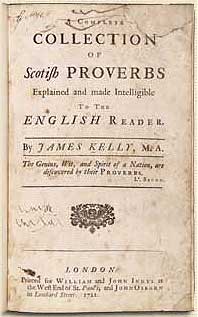

English proverbs were collected as early as the twelfth century in Proverbs of Alfred. As well as being a means of personal admonition or comment, they served for general instruction and were used in schools and by tutors to teach reading and moral development simultaneously. By the eighteenth century, they were such an integral part of speaking and writing that they appeared as parts of dictionaries. The title page of Dictionarium Britannicum, published in 1736, provides a list of what is inside, including words, etymologies, and “A Collection and Explanation of English Proverbs.” Other volumes were dedicated solely to adages, such as Thomas Fuller’s Gnomologia: Adages and Proverbs, published in 1732; and James Kelly’s Complete Collection of Scottish Proverbs, printed in 1721. Robert Burns, in a 1788 letter, gives an example of a Highland axiom: “Kings’ caff is better than ither folks’ corn.” By “caff” he meant “chaff.”

The familiarity of proverbs bred contempt among people who considered them vulgar expressions. “Triteness and triviality are fatal to a proverb,” said Isaac D’Israeli—father of Benjamin—late in the eighteenth century. Writing in 1741, Lord Chesterfield advised his son to “most carefully” sidestep

an awkwardness of expression and words . . . such as false English, bad pronunciations, old sayings, and common proverbs. . . . If, instead of saying that tastes are different, and that every man has his own peculiar one, you should let off a proverb and say, That what is one man’s meat is another man’s poison . . . everybody would be persuaded that you had never kept company with anybody above footmen and housemaids.

Voltaire said that many questions about human nature “may

be reduced to the vulgar proverb: Was the hen before the egg,

or the egg before the hen? The proverb is rather low.” On

the other hand, the French thinker could employ a dictum he found

useful, writing that “it is a good proverb which says that

‘it is better to be envious than to have pity.’ Let

us be envious, therefore, as hard as we can.” And he could

pen his own maxims, such as “It is dangerous to be right

when the government is wrong.”

Samuel Johnson, a poet, essayist, and the creator of the 1755 Dictionary of the English Language, loved words, but could not abide proverbs, according to Bartlett Jere Whiting, the author of Early American Proverbs and Proverbial Phrases. Whiting says Johnson rarely quoted proverbs “in his own right and seldom introduced them into the remarks of his fictitious characters.” Whiting concludes from his research that “by the middle of the eighteenth century there seems to emerge a feeling in the mother country as well as in America, that proverbs, at least taken seriously, have little place in elevated literature.” Alexander Hamilton sniffed at “trite proverbs,” and it is difficult to unearth proverbs in anything Jefferson wrote, even in his informal letters to friends and relatives. When he included one in an 1820 letter to Maria Cosway, it seems a particularly Jeffersonian touch that he used a maxim from a foreign language. “Such is the present state of our former coterie: dead, diseased, and dispersed,” he said. “But ‘tout ce qui est differé n’est pas perdu,’ says the French proverb.” Roughly translated, it means, “What is put off is not lost.”

James Kelly parsed Scottish proverbs for a foreign audience—the English.

Another Virginian was perhaps more tolerant of proverbs. The 1762 edition of The Virginia Almanack included a section of 100 proverbs and anecdotes. George Washington marked fifteen with an “X,” maybe signifying that he found them interesting or amusing. In a 1786 letter, Washington informed a correspondent that a recent visitor, “keeping in Mind the old proverb, was determined not to make more haste than good speed in prosecuting his journey to Georgia.”

New proverbs emerged, sometimes on their own. In 1773, for example, a real bull charged through an actual china shop in London, giving rise to a saying still in use in the twenty-first century. Other proverbs from that time are somewhat familiar to modern ears, like “grin and abide” from 1794, akin to “grin and bear it;” “ill got, ill gone,” from 1753, a variant of “easy come, easy go;”and “trust every man so far as we can see him” from 1718, in lieu of “as far as you can throw him.”

Some maxims from 250 years ago have lost their meaning: “No fence against a flail,” used in 1730, is an example; another is “festina lente,” which was employed by Henry Fielding in Tom Jones. Meaning to “make haste slowly,” it may have been in the back of Washington’s mind when he wrote “make more haste than good speed.”

There are those eighteenth-century proverbs no longer in use that still ring true, such as “Once every seven years, the worst husbands have the best corn.” “Husband” here meant “husbandman” or “farmer.” People better versed in technology than agriculture are more likely to say that “a stopped clock is right twice a day.”

Whatever the source or derivation, proverbs new and old are distinguished, and always have been, by an applicability to a particular event or in a specific context. Consider, in terms of Colonial Williamsburg, chapter 22, verse 28, of The Proverbs: “Remove not the ancient landmark, which thy fathers have set.”

Jim Breig, an Albany, New York, writer and editor, contributed “Speaking of the Past: The Words of Williamsburg” to the summer 2001 journal.

Try your hand at 18th-century proverbs with our online proverbs game