The Tale of the Red-winged Blackbird

Text by Pamela J. Young

Photos by Mary Studt

George Edwards’s watercolor after conservation.

The travelling exhibition Mark Catesby’s Natural History of America: The Watercolors from the Royal Library, Windsor Castle drew to a close at the DeWitt Wallace Museum in February 1998 while the paper conservation laboratory prepared works on paper from the permanent collection for a replacement exhibit titled Drawing on Nature. In the midst of the activity, Margaret Pritchard, curator of prints, maps and wallpaper, came to the lab with eleven watercolors depicting North American birds. They were offered for sale, unattributed but clearly in the style of several well-known eighteenth-century European artist- naturalists represented in the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation collections, among them Catesby, George Edwards, Eleazar Albin, and Georg Ehret.

These men were colleagues and collaborators in the business of documenting flora and fauna of the New World. Their clients included wealthy speculators on both sides of the Atlantic interested in exploiting the natural resources of the American colonies. The provenance indicated that these paintings were originally part of a larger group owned by John Drayton of Charleston, South Carolina, a colonist of stature and position. Two paintings held immediate interest for the curator because they appeared to be direct copies of prints included in the first set of Mark Catesby’s Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, 1731-47, a seminal volume in the study of flora and fauna of the American British colonies. They were the Whip-or-Will or Lesser Goat Sucker and the Red-winged Blackbird. Could these be previously unknown Catesby works?

George Edwards’s watercolor before conservation. Varnish and grime had obscured the painting’s original vibrance.

The initial examination revealed two types of paper within the group, each with an obvious mould pattern and many with at least a portion of a watermark. A standard implement in eighteenth-century papermaking, the mould was constructed of a wooden frame strung with a woven copper wire screen. Often a watermark was sewn with wire onto the screen, in essence a trademark designating the paper mill and production date. The wire patterns leave a distinct impression on the sheet of paper formed with the mould and become identifying marks. The patterns in the watercolor paper were reproduced by a simple tracing on polyester film so that the curator could take them to England for comparison with similar paintings in the Sloane Collection at the British Library. Sir Hans Sloane, a collector of natural history illustrations and specimens during the first half of the eighteenth century, had inscribed title and artist on many paintings as they entered his collection. In fact, when the Mylar facsimiles were compared with paper supports in this collection, the mould patterns and watermarks matched exactly those paintings attributed to George Edwards. Consideration of materials and technique used by the watercolorist confirmed that the English naturalist George Edwards had painted all eleven.

Infrared photography, left, and illumination under an indirect light source, right, disclosed details invisible to the naked eye. Conservators saw a graphite pencil underdrawing and narrowed the identity of the pigments in the shoulders.

Aside from the historical importance of the Edwards bird illustrations owned by John Drayton, one of the paintings provided a treatment challenge for the foundation’s paper conservators. The Red-winged Blackbird had a disfiguring varnish layer that obscured the body and wings of the bird. Drying and contraction of the coating had caused the watercolor paint to crack and cup, pulling the uppermost layer of paper fibers with it.

Because the design for Edwards’s watercolor rendering clearly was taken from Catesby’s print of the same subject, colors and details in Catesby’s print suggested the thick, brown varnish concealed similar brilliant elements in the painting. Through conservation treatment, the curator and conservators hoped to confirm the maker’s identity and return the appearance to a state closer to the artist’s original intent.

Did the artist apply the varnish? Why was the varnish applied? Of what was the varnish composed? Could the varnish be removed without damage to the watercolor paint below? Using analytical techniques, answers to these questions began to unfold.

Infrared reflectography employs an infrared, that is, heat, radiating light source, a standard format camera, and infrared sensitive film. This technique produced high-contrast black-and-white photographic images that supplied information about the pigments and details beneath the varnish. Unlike visible light, infrared radiation penetrated the darkened coating and was absorbed by carbon-based media, creating a picture of the bird delineated in a graphite pencil underdrawing and black watercolor paint. Graphic rendering of feathers and features of the head was revealed. Careful modeling of the form became apparent. White spots visible on the reflected infrared photographs correspond to small pieces of debris lodged in the varnish, and the crackle pattern caused by the varnish is visible.

The varnish was removed and the painting rinsed with patient care.

X-radiographs, or images recorded with X-ray sensitive film, were useful in narrowing the identity of the pigments used to color the bird’s shoulders, areas too dense for X rays to penetrate. Lead- and mercury-based red and yellow pigments are probably responsible for the ghostly image of the epaulets floating in the black background of the radiograph we made.

Although the varnish probably was applied to enhance the appearance of the watercolor paint, the conservators and curator believed the artist did not apply it.

In many areas of the painting, varnish strays from the edges of the watercolor and overlaps the unpainted paper. Because the bird is painted in an otherwise precise manner, it seems unlikely that the artist would have applied the final layer carelessly.

The varnish was impure. Small pieces of debris lodged in it suggest it was contaminated originally or that the painting dried in a dirty environment. Curator and conservators doubted the artist was unconcerned with the quality of varnish applied to such a precisely rendered subject.

Only one other watercolor by Edwards is known to be varnished, and it has the same history of ownership as the blackbird now in Colonial Williamsburg’s collection, a gift of Sumpter Priddy.

These observations suggest the varnish was added by a subsequent owner.

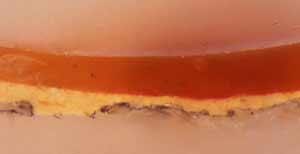

A tiny sample was taken from the body of the bird, set into a plastic resin cube, ground, polished, and viewed in cross-section under a microscope to help determine the stratification and sequence of layers. Results of chemical tests and technical analysis showed the varnish was gum arabic.

Gum arabic is the binding medium used in watercolor paints, but is traditionally used as a varnish too. In the eighteenth century, gum arabic would have been a common material in the artist’s store, but could be found as well in pharmaceuticals, confectionery, and industrial products. In watercolor painting, varnish is a barrier to moisture, fly specks, and surface abrasion. Varnish was applied to imitate the appearance of oil paintings, to saturate dark pigments and add detail with high gloss. A traditional preparation entails soaking in hot water the “tears,” or dried lumps of gum, exuded by acacia trees of Africa, India, and Australia, then the decanted liquid is used. Ralph Mayer’s A Dictionary of Art Terms & Techniques includes this note on preparation: “When a solution of gum arabic is heated to the boiling point its character changes: It becomes dark, acquires a pronounced odor, and will not function properly in the recipes calling for a hot water solution; however, it may be used as a paper adhesive.”

So the answer to our second question became apparent with a little deductive reasoning. The varnish resembled a dark accretion on the verso of the painting, possibly the remains of gum arabic used to adhere the painting into a folio as was done typically in the eighteenth century. It seemed plausible then that whoever fixed the painting into the folio may have applied the varnish as well.

Removal of the crackled varnish was undertaken to reduce stress on the paint layer and paper, and to reveal details obscured by the turbid coating. This procedure involved softening and swelling the varnish with a watery poultice, then gently scraping away the thickness with fine tools. Small squares of blotter and tiny cotton swabs were used to further reduce the residue. This treatment was accomplished one square centimeter at a time with the aid of a microscope to avoid damage to the delicate paint beneath.

During treatment, which required 250 hours, conservators dealt with tiny cracks in the watercolors

Once the bulk of the varnish had been removed, the painting was “washed” to reduce discoloration and acidity in the paper. Using a suction table, conditioned water was sprayed over the surface of the painting. By means of the suction, the water was pulled quickly through the painting paper, rinsing stains and discoloration into blotter paper below.

Metallic particles left in the paper from the manufacturing equipment had corroded and caused disfiguring degradation. The bits of metal were removed and the surrounding paper was treated with a neutralizing solution.

Conservaors examined varnish cross sections with a microscope.

A weak chemical solution of bleach was applied with a fine hair brush to areas of severe staining and discoloration in the paper. The treatment was performed in a controlled manner, again working under the microscope. The bleach was removed from the paper by rinsing with deionized water on the suction table.

Paper intended for writing or drawing is sized during manufacture, and tradition requires dipping the dried sheet into a warm gelatin solution. Sizing provides paper with strength, protection against deterioration, and resistance to liquids, and smooths the surface texture. When a paper artifact undergoes an aqueous treatment, sizing may be removed, thus changing the paper qualities. The blackbird painting was resized with gelatin to return strength to the paper and to enhance the image. The resizing also provided an isolating layer between Edwards’ original watercolor and the conservator’s inpainting.

Flakes of paint had been lost along cracks in the varnish. The last step of treatment required inpainting, that is, filling the losses with color just within the boundaries of the loss. If left unfilled, the losses would distract the viewer. This step restored the integrity of the image.

Tears were mended with Japanese paper and starch paste, standard materials in the conservation of works on paper. Japanese paper is relatively thin, but the fibers are long and provide strength. Lightweight and supportive, these papers are torn into narrow strips for mending or attached as sheets to provide linings. The adhesive most commonly used is wheat or rice starch, made by mixing the dry starch powder with water and cooking until thickened and tacky. The water-soluble paste can be removed easily if necessary.

For exhibit and storage, the painting is housed in acid-free ragboard mats and framed with period reproduction moulding. Print storage conditions conform to strict standards of temperature and relative humidity for long-term preservation.

Mark Catesby’s Red-winged Blackbird, printed in his Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands, was Edwards’s model.

It is difficult to guess how long it might have taken George Edwards to create The Red-winged Blackbird, perhaps a day. The treatment that revealed the artist’s technical mastery required another 250 hours of skill and sensitivity, and we like to think Edwards would be pleased that his striking image has been renewed.

Pamela Young is a Colonial Williamsburg conservator making her first appearance in the journal. She thanks colleague Margaret Pritchard for sharing her research.