The Freshest Advices

Conservators Discover Unknown Williamsburg Artist

Bob Doares of Colonial Williamsburg’s department of staff development helped the journal round up illustrations for his autumn-issue article on a nineteenth-century Williamsburg jurist, teacher, poet, and novelist. In one of them, he discovered, there was a good deal more than met the eye. His account:

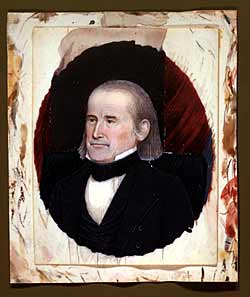

An unknown Williamsburg artist came to light when Cynthia Barlowe lent the journal a miniature portrait of her great-great-grandfather, Nathaniel Beverley Tucker. The image, secured in a pocket-size, velvet-lined, hinged leather case, had been displayed for generations in the bowfat of the “blue room” in the Historic Area’s St. George Tucker House, but it had not before been published.

A note written in the hand of Cynthia Beverley Tucker Coleman-Tucker’s daughter and Barlowe’s great-grandmother-accompanies the likeness. It reads: “Judge N. Beverley Tucker / Not at all like him.”

Barbara Luck, Colonial Williamsburg’s curator of paintings, drawings, and sculptures, said, “Though the modeling of the face is somewhat flat, the painting is meticulously done and not so amateurish as to make it an obvious example of folk art.”

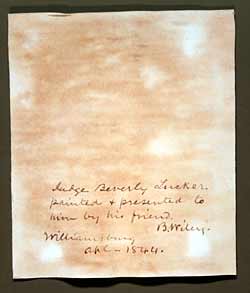

When

conservator Amy Fernandez gently pried the Tucker miniature, right,

from its case, she and her colleagues found the inscription at

left.

- Tom Green

Curious about the painter’s identity, Barlowe asked whether Colonial Williamsburg could remove the picture from its case to look for an inscription. Luck arranged an inspection by conservators Amy Fernandez, Betsy Geiser, and Stephanie Conforti. All were loath to attempt an extraction that might damage what Luck thought to be a watercolor on fragile ivory. Fernandez, prying with a tiny spatula, loosened the glass and dismantled the double-matted ensemble.

The portrait was watercolor and gum arabic on an eggshell-thin rectangle of ivory 2 13/16 inches by 2 3/16 inches, affixed to a secondary mount of vellum or paper, the margins bearing the artist’s test brushstrokes. Microscopic examination showed striations in the ivory’s surface left by whatever implement peeled the piece off its tusk. There is no signature on the painting itself, but brown ink script on the back of the mount reads: “Judge Beverly Tucker, painted & presented to / him by his friend. / B. Wiley. / Williamsburg / apl - 1844.”

Wiley? Shrugs from all in the lab belied growing excitement about this apparent discovery of a new Williamsburg painter. A quick check of Earl Gregg Swem’s Virginia Historical Index yielded tentative identification in the person of Bernard Wiley, one of Tucker’s students of law and government at the College of William and Mary from 1843 to 1845. College records show that Wiley was the ward of William and Lydia Wiley Ellis, who owned a 4,000-acre farm near Savannah in northwestern Missouri. Tucker left Williamsburg in 1816 and spent seventeen years in St. Louis and in central Missouri as an attorney and circuit judge before returning to Virginia in 1834. Wiley entered William and Mary at 22 and boarded successively in the Williamsburg homes of Dr. Galt and J. J. Jones. The young scholar captured his 59-year-old professor’s likeness at Tucker’s professional and intellectual peak, the year Tucker’s third novel, Gertrude, appeared in serial form in Richmond’s Southern Literary Messenger.

Further evidence identifying Wiley as the portraitist who styled himself Tucker’s “friend” came from Cynthia Barlowe and Margaret Cook, curator of rare books and manuscripts at the college’s Swem Library. In the Tucker-Coleman Collection there they found two letters from the judge’s future brother-in-law, William Berkeley of Loudon County, Virginia. They mention Wiley in connection with Army troops fighting in Mexican territory.

The first, dated March 26, 1847, reports news from a second lieutenant identified only as Frank and stationed in Albuquerque, who a few months before “went out as far as Santa Fe in company with old Wiley, who is a private in one of the volunteer companies. I am afraid that from recent accounts they have had a bad time of it.”

Writing from New Orleans on June 25, Berkeley says Colonel Alexander Doniphan’s “men are here, being paid off. I have seen several officers who were acquainted with poor Wiley. He had many devoted friends at Santa Fe, and had he lived, would have been elected to the command of a company.”

Military records at the National Archives show Private Bernard Wiley lay “sick in Hospital at Santa Fe, N.M.,” in December of 1846 and died February 1, 1847. The fledgling lawyer had returned to Missouri from Williamsburg by the time President James K. Polk declared his war of conquest of the Southwest in early 1846. Wiley answered the call for soldiers, mustering as a rifleman into Colonel Sterling Price’s 2nd Missouri Regiment of Mounted Volunteers at Fort Leavenworth, August 5, 1846. Thirteen days later, Price’s regiment marched unopposed into Santa Fe with the army of General Stephen Watts Kearney.

Thus Wiley joined thousands of young Americans looking for adventure and glory in the war against Mexico. What most of them got was heat, dust, boredom, insects, and disease-which killed more men than bullets. Wiley seems to have succumbed to some pestilence in New Mexico halfway through his twelve-month enlistment. In 1848, the Army paid Wiley’s mother a death benefit of $99.78, about three times the assessed value of the horse he rode.

This unfolding story of a young artist, lawyer, and soldier cut off in his prime has sparked interest and speculation in Virginia and Missouri. Laurel Boeckman of the State Historical Society of Missouri says, “It is probable that Wiley was exposed to the work of renowned Missouri River painter George Caleb Bingham, another transplanted Virginian, who began his career as a portraitist about 1833, when Bernard Wiley was just a boy.”

Young Wiley could have met the elder artist. Wiley was a friend of the Tuckers, and Bingham resided and painted in Saline County, Missouri, where, in 1830, Tucker married Lucy Ann Smith and established his plantation, Ardmore.

Curator Luck wonders whether there are other examples of Wiley’s work. “With his ability, I cannot imagine he didn’t sit around the campfires and sketch scenes of army life.” No other works have surfaced.

“This discovery,” Luck says, “is the stuff art historians love. Not only do we have an inscription identifying the subject, date, locale, and painter, but also the critical comment of someone who knew the sitter. But the story of this picture is more than all that. It is the documentation of a friendship.”

Barlowe says, “I was telling Margaret Cook I thought it was so sad that ‘poor Wiley’ died so young and obviously had lots of talent and training. Margaret said that we had actually brought him back to life in our own way, and that made me feel better.”