Steve Archer

A replica statue of Lord Botetourt, one of Virginia’s last royal governors, stands in front of planting beds excavated in the College of William and Mary’s Wren yard.

Dave Doody

A midnight raid by the British in 1775 removed the colony’s supply of powder from the Magazine and enraged citizens.

Tom Green

After Dunmore abandoned the Palace, townspeople broke in and removed a “large collection and valuable” of arms.

Internet Archive

July 9, 1776, patriots tore down a statue of King George III in New York, transforming the lead into bullets to fight his army.

Library of Congress

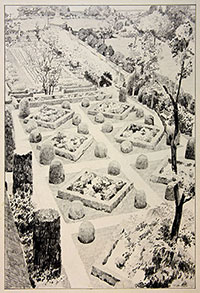

The College of William and Mary’s front and rear gardens in the 1782 Rochambeau map

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., Library

In Thomas Mott Shaw’s rendering, Colonial Williamburg architects Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn reimagined what the Palace looked like on the eve of the Revolution. Near the west end of Duke of Gloucester Street, the Palace balanced the Capitol one mile down on the east side.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., Library

A Shaw sketch of the garden behind the Palace, arranged in roomlike segments, bordered by a long, high wall. Varying measures of archaeological evidence, historical record, contemporary description, and educated inference went into restoration of the colonial capital.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., Library

The graves of Revolutionary soldiers were found on the Palace grounds.

Colonial Williamsburg

Designs for the Palace and the Capitol were informed by the Bodleian Plate, found in 1929.

Architecture, Archaeology, and the Revolution in Williamsburg

by Edward A. Chappell

Revolution changes communities, intentionally and unintentionally. Among other things, it shifts the character of buildings and landscapes by removing symbols of an old order. Architectural history is written by destruction as well as by construction.

The shifts often depend on the ideology as well as the reach of the revolutionaries. The English Civil War destroyed fixtures and monuments in churches that Puritans saw as idolatrous, replicating on a smaller scale the demolition of monasteries by Henry VIII in his bid to establish preeminent religious authority in England. The French Revolution sanctioned vandalism, cleansing the landscape of papal accoutrements seen as buttressing the Old Regime. In 1871, the Paris Commune sought to overthrow authority by destroying the Tuilleries. Communards also pulled down Napoleon’s high Vendome column, calling it a “symbol of brute force and false glory.” More state-sponsored mob violence destroyed palaces, grand houses, and peasant villages in the restructuring of society in the Union of Socialist Soviet Republics and Eastern Europe. Mao demolished Beijing’s city walls and gates as a first step toward modernizing the Chinese capital to symbolize the destruction of imperial authority as well as to open the city up to vehicular traffic.

The characteristics of the population as well as ideology affect what happens during popular revolt. Colonial Boston had an appetite for mob violence, as Governor Thomas Hutchinson discovered when, enraged by the Stamp Act in 1765, a mob attacked his house, smashing doors and windows, and tearing out woodwork and partitions. The ruffians were not satisfied until they threw down a cupola on the roof from which the governor and his guests once enjoyed vistas of the North End and Boston Harbor. Hutchinson was lucky to escape with his skin.

Such local Williamsburg elites as Peyton Randolph were more in control of the town’s smaller population. Patrick Henry had to assemble a militia in Hanover County, fifty miles away, to march on Williamsburg when Virginia’s governor, Lord Dunmore, directed royal marines to clandestinely remove fifteen half-barrels of the colony’s gunpowder from the public Magazine one April night in 1775.

Dunmore viewed Williamsburg citizens as little better than a Boston mob. After abandoning the Governor’s Palace for a British warship, he condemned groups of men who forced their way into the building and took what they liked. “They broke open every lock of the doors of all the rooms, Cabinets and private places, and carried off a considerable number of Arms of different Sorts, a large collection and valuable.” It was, he wrote, “an infamous robbery, this violation of private property as well as atrocious outrage against the King’s Authority.”

Virginians interpreted the removal of firearms and edged weapons from their ornamental hanging in the Palace differently. To them, it was an orderly and public action to secure the arms in the bright light of day, in contrast to Dunmore’s nighttime raid on the Magazine. They took three carts through the main streets, each accompanied by respectable citizens, and planter-politician Theodorick Bland inventoried the arms. They published a letter to Dunmore that said they acted in the interest of security, moving the arms from the periphery of the town to its public core. The arms were issued and used by Virginia forces, and archaeologists have found pieces of the ornamented infantry small- swords at such Williamsburg sites as the Palace, Magazine, and James Geddy workshop.

Revolutionary attacks on property in Williamsburg were focused on overt symbols of royal authority. The General Assembly paid builder Benjamin Powell to remove carved royal arms from the pediment of the two-story Capitol portico, which had faced down Duke of Gloucester Street since mid-century. As in almost every restive colony, royal portraits disappeared from the walls of public buildings. Virginians removed paintings of George III and Queen Charlotte, although likenesses of earlier monarchs were still hanging in the Capitol in 1777. Only the hand of one queen, resting on her crown, survived a clean sweep of official canvases in South Carolina, cut from a portrait of Charlotte—or was it Queen Anne? The hand’s identity is long lost, but not its potency as a trophy.

Militiamen cut lead from the Virginia Capitol roof for bullets, a less theatrical gesture than New Yorkers’ pulling down the gilded lead statue of George III toward the same purpose. There is archaeological evidence that an ornamented wrought-iron fence and gates at the Palace were carted across town to James Anderson’s armory, presumably for material for weapons work rather than repair and regilding.

The new Virginia Assembly met in the Capitol from 1776 through 1779—when the government moved to Richmond—and the first two commonwealth governors took up residence in the Palace, broken locks notwithstanding. The new revolutionary governor Patrick Henry lived in the ransacked old official residence at the end of Palace Street.

Much of Norfolk, Virginia’s principal port, was destroyed early in January 1776. Once the damage was blamed on Dunmore’s demolitions and naval shelling, but now it is partially attributed to revolutionaries burning the houses and stores of loyalists. Such partisan vandalism appears to have been limited in Williamsburg. There were no recorded attacks on the houses of such loyalists as Attorney General John Randolph and merchant George Pitt, despite the tempting target offered by Randolph’s imposing wooden house on south England Street. The marble statue of Lord Botetourt in the Capitol loggia was unmolested until after the Revolution, the assembly paying Humphrey Harwood to have it cleaned four times between 1777 and 1779.

When militias and armies occupied Williamsburg during the Revolution, most intentional destruction was strategic. The British destroyed the U-shaped barracks built for Continental forces on what had been the governor’s property north of town but seem only to have demolished the forges at the armory near the Capitol, not the armory itself or the tinshop. An accidental fire on the Anderson block in 1842 and Federal soldiers’ burning of the college building in 1862 appear from archaeology to have been more destructive. Neither side smashed the baroque funeral monuments of past governors or gentry or stole the silver coffin fittings from Botetourt’s tomb below the College chapel—left for soldiers to do during the 1862–65 Union occupation.

Nevertheless, the Revolution affected the town. The war precipitated moving the seat of government west to Richmond at the end of 1779, setting the scene for Williamsburg’s restoration a century and a half later. Although the town remained an active community after the war, the absence of state government and the commerce that went with it reduced development of the sort that transformed such other state capitals as Philadelphia and Hartford. No more would councilors, burgesses, and litigants assemble at legislative seasons or Native Americans come to address treaties with the governor.

The Revolution made Williamsburg a more ordinary community, removing the trappings of old authority, as well as most of the action. British and Virginia leaders had planned and built Williamsburg as a structured, hierarchal community, intended as a physical expression of institutional and civic order for the official center of the agricultural colony. Unlike jumbled and scruffy Jamestown, it was designed to have wide, straight, orthogonal streets balanced where they divided at either end of the town.

The Capitol rose at the east end of the main boulevard, a mile from the College of William and Mary in Virginia at the west end. By 1709, the Palace for the governor or his resident lieutenant, stood at the end of a broad northern cross-axis. Like the college building, they were given tall cupolas that focused attention on the edifices and offered heights from which to survey the landscape. All three buildings were recessed from the street within spaces that set them apart from the general populace.

By 1715, Bruton Parish built a church next to its seventeenth-century predecessor near the intersection of these two vistas. The king’s representatives took interest in such matters. Lieutenant Governor Francis Nicholson conceived the town plan. Lieutenant Governor Alexander Spotswood adjusted it, and designed the new church as well, four years later, along with the octagonal Magazine, centered in the southern half of Market Square.

Eighteenth-century Williamsburg was arranged for the pomp and public display of authority. As a map drafted in 1782 by a garrisoned Frenchman and decades of archaeology illustrate, nearly every property was fenced to stake out private lots, defend them against foraging animals and trespassers, and subdivide the spaces by function. The average fence height may have been five to six feet, made of materials appealing as firewood for soldiers bivouacked in the town. Most public buildings were more substantially enclosed. Brick walls with spiky gates encircled the Capitol and church. The Capitol gates had ceremonial significance. The Virginia Gazette reported in 1768 that upon arriving in Williamsburg, the new governor, Lord Botetourt,

Stopped at the Capitol, and was received at the gate by his Majesty’s Council, the Hon. The Speaker, the Attorney General, the Treasurer, and many other Gentlemen . . . after which being conducted to the Council Chamber, and having his commissions read, was qualified to exercise his high office, by taking the usual oaths.

An engraved copper plate found in the 1920s at Oxford University’s Bodleian Library shows the front of the Palace as walled, with a curving outer curtain broken by piers carrying a lion and unicorn. High walls with crenellated tops flanked the building itself. Beyond, the governor’s garden was divided into ornamental segments, like rooms in a great house. Most formal was the long central space, with high walls capped by imported stone balls. At the far end were a fence and gates made of wrought iron, keeping open the extended view of the governor’s farm, or what was usually called his park.

This cultivated ceremonial landscape lost its purpose during the Revolution. The bodies of more than a hundred Continental soldiers, most casualties of the Siege of Yorktown, were buried in one set of four parterres, creating a large archaeological fossil of Dunmore’s garden plantings and walks. Eventually, the walls were pulled down. Most of what we know about the Palace grounds comes from excavations done for its reconstruction. The governor’s icehouse and a stone finial were all that survived partially above ground.

A parallel story is being revealed at the College of William and Mary, founded by royal decree in 1693. The Bodleian Plate shows a formal landscape there, too, with artificially shaped evergreens marching in parallel lines along the axis between the main building and Duke of Gloucester Street. Recent archaeological work uncovered the edges of planting beds and holes, confirming testimony that the college yard was a formal landscape until the Revolution. In 1777, Ebenezer Hazard described it as “a large court yard, ornamented with gravel walks, trees cut into different form, and grass.” At the front of the college, like the large gridded gardens the richest Virginians created as settings for their plantation houses, this was more in public view than the Palace garden. Nevertheless, access had its limits.

In 2011, the Colonial Williamsburg–William and Mary archaeological field school taught by Mark Kostro found long-filled postholes from fences that, from early in the eighteenth century until the 1780s, enclosed the garden. There were four generations of fences, the earliest older than the 1723 construction of the Brafferton building, intended for an Indian school, and the last removed at the end of the Revolution. A posthole abandoned and backfilled during cleanup after the war contained the carved neck of a baroque stone finial.

It is the sort of ornament placed on brick pillars framing fences, walls, and gates that enclosed the most lavish settings of Virginia plantation houses like Westover and Kingsmill. The fragment is more ornamented than most surviving from eighteenth-century Virginia, and it probably came from one of the gateways that opened into the precinct of the college. Peering carefully at the Bodleian Plate, one can see the engraver included two such gateways facing the sides of the main building. Corroborating evidence, including archaeology and surviving fabric, have proven much of the detail in the Bodleian Plate accurate. If the side gates existed, they suggest that another stood guard at the front of the garden, on axis with the street and limiting entry to the manicured setting of the college. Gates, wood fences, and ornamental plantings disappeared in the 1770s and 1780s. The yard took on the informal, unevenly planted guise that it still enjoys, open to all comers.

Archaeology will reveal more about the college’s early setting, but the excavation shows that its immediate precinct was a dramatic part of the hierarchical town. It also shows that the college’s armatures of authority were swept away at the end of the eighteenth century, when the town settled into its reduced new role, a scene of modest trade and solely local administration. The prim Williamite landscape became impractical and out of step with the politics and financial realities of a newly impoverished school in a small town of a young republic.

If the Revolution as it touched Williamsburg was a gentlemanly war compared with later conflicts, there were losses. After Yorktown, the Palace, then a soldiers’ hospital, burned, as did the college’s President’s House when it became a hospital for French officers. A district court sat at the Capitol, which also briefly served as a grammar school. Much of the building was battered by 1796, when architect Benjamin Latrobe said that young would-be revolutionaries attacked Lord Botetourt’s statue and knocked off his marble head. The eastern and middle sections of the Capitol were demolished, and the west wing and its classical portico burned in 1832. Its paving was hauled away, and stone elements of the columns were left for archaeologists to find nearby. Accidental or not, these were losses contributing to the gradual postwar removal of the markers of regional and imperial authority. In the process, Williamsburg changed into a picturesque town travelers visited and whose past glories, revolutionary and otherwise, they wrote romances about.

Colonial Williamsburg’s Shirley H. and Richard D. Roberts Architectural Historian, Ed Chappell contributed to the summer 2012 journal a story about the reconstruction of the James Anderson Armoury.