Online Extras

Prison Reform Slideshow

Entering the gaol in irons, interpreter Dan Moore as a miscreant who could face death for stealing a handkerchief.

Female paupers from outside London were confined seven days in Bridewell’s pass room before being shipped to their parishes.

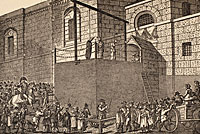

Outside the debtor’s door of Newgate Prison in London, opposite the Old Bailey, the hangman plies his trade with another client.

Cruel and Unusual

Prisons and Prison Reform

by Jack lynch

In The Scarlet Letter, Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote, "The founders of a new colony, whatever Utopia of human virtue they might originally project, have invariably regarded it among their earliest practical necessities to allot a portion of the virgin soil as a cemetery, and another portion as the site of a prison."

Prisons were among the first public buildings erected in the New World. Boston felt the need of a "house of detention" when the city consisted of a mere forty homes. But the eighteenth century transformed not only the physical form of those prisons but their function and their place in American consciousness.

Early American prisons were not conceived as houses of punishment. In English and American law, political prisoners and high-ranking prisoners of war were occasionally incarcerated, but few common criminals could expect such treatment. Almost the only time commoners were locked away was while awaiting trial—once a verdict was delivered, they were punished on the spot or released. This place of confinement, then, was properly speaking not a prison but a jail—often spelled "gaol" or "goal" in the eighteenth century.

The only offense for which long-term imprisonment was common was debt, though this presented a paradox. Wealthy debtors who had money but refused to pay might be persuaded by the prospect of imprisonment to settle their obligations.

Locking up the poor, though, guaranteed they could never earn the money they owed, and this struck many as absurd. The New York legislature said in 1732 that "many poor persons may be imprisoned a long time for very small sums of money … to the ruin of their families, great damage to the public who are in Christian charity obliged to provide for them and their families … and without any real benefit to their creditors." Yet only in the 1830s did the United States begin to abolish debtors' prisons.

For other offenses there were four broad classes of punishment: fines, public shame, physical chastisement, and death. Most misdemeanors were punished with fines, as is the case today. Some more serious crimes were punished with public shame, whether with a demand for a public confession, a term in the stocks, or a mark to identify the malefactor's offense. Hester Prynne's scarlet A for "adulterer" is the most famous mark of this kind, but, points out Scott Christianson—a journalist specializing in prisons and the death penalty—others were marked with "'B' (blasphemer), 'D' (drunk), 'F' (fighter), 'M' (manslaughterer), 'R' (rogue), and 'T' (thief)." Shaming had largely fallen from use by 1700, as cities grew larger and public disgrace no longer had its desired effect. A step up from public shame, then, was physical chastisement—convicts might suffer flogging, branding with a hot iron, or the loss of their ears.

The eighteenth century is a fascinating period in the history of capital punishment, for crime was much on eighteenth-century minds. The rise of trade, the development of early capitalism, and the beginnings of the Industrial Revolution transformed the economy, and all of these made crime more prevalent, or at least more obvious to the public. Fears of pervasive criminality provoked a get-tough-on-crime frenzy, and more and more crimes were designated capital. In England, the legal system became known as "the Bloody Code": between 1688 and 1815, the number of capital crimes rose from about fifty to more than two hundred. The theft of a silk handkerchief or a pocket watch might lead to execution.

The death penalty loomed large in eighteenth-century statutes, but there were ways to escape a sentence to the gallows. English courts could show mercy by transporting convicts first to North America, then, after independence, to Australia, for sale as servants. Jonathan Boucher, a friend of the Washington family, reported that young George's education came from "a convict servant whom his father had bought for a schoolmaster."

The medieval "benefit of clergy" allowed priests to avoid the harsh penalties associated with the secular courts; eventually anyone who could read a Bible verse, or recite one from memory, could avoid the harshest penalties. Thomas Jefferson found it risible: "This privilege, originally allowed to the clergy, is now extended to every man, and even to women. It is a right of exemption from capital punishment, for the first offence." Parliament did away with the much-abused literacy test in 1706. Pregnant women convicts might "plead their bellies" and avoid, or at least postpone, execution. Criminals might also hope for pardons from a king or governor. There were instances of jury nullification—juries ignoring the facts of a case to avoid the necessity of imposing what struck them as unduly harsh punishment.

Still the harsh punishments remained on the books, and this led some American theorists to rethink the role of the prison. In an age of unprecedented social theorizing, many called for a thorough revision of the penal system, and suggested that jails might be useful for something other than holding suspects until trial.

As early as the 1680s, Pennsylvania Quakers were campaigning against the death penalty, urging incarceration as a humane alternative. They may have been thinking back to Tudor England's workhouses. Starting in the 1550s, persons convicted of leading a "Rogishe or Vagabonds Trade of Lyef" were sent to Bridewell, a former royal palace converted into a workhouse. By the 1570s, similar buildings were constructed around England, and "bridewell" became a common noun for a workhouse. In the 1780s and '90s, a group of Quakers known as the Philadelphia Society for Alleviating the Miseries of Public Prisons began advocating for something similar in their new nation. Others took up their cause in what historian Blake McKelvey calls "one of the products of the social and humanitarian revolution that contributed so generously to the founding of the American nation."

In the years after the Revolution, Americans were reconsidering the function of punishment on practical, political, theological, and philosophical grounds.

Reformers approached the question pragmatically, asking whether harsh penalties really deterred crime. Some said that an indiscriminate system of punishment encouraged criminals to be similarly indiscriminate in their offenses. When the penalty for theft, for example, is the same as the penalty for murder, rational thieves will realize that it makes no sense to leave witnesses to their crimes. As Samuel Johnson noted in England in the 1750s, "If only murder were punished with death, very few robbers would stain their hands in blood; but when by the last act of cruelty no new danger is incurred and greater security may be obtained, upon what principle shall we bid them forbear?"

There was similar thinking in North America, and in the years after the Revolution, it began to show up in the statutes. State after state began reducing the number of death-penalty offenses: in 1786, for instance, Pennsylvania eliminated the death penalty for robbery, burglary, and sodomy. In a few years, only murderers were eligible for capital punishment. The United States Congress established an investigative committee to consider "milder punishments for certain crimes for which infamous and capital punishments are now inflicted." It was largely on pragmatic grounds that Jefferson, helping to revise Virginia's statutes in 1776, proposed a bill to eliminate the death penalty for many crimes. "On the subject of the Criminal law," he wrote of the legislative debates, "all were agreed, that the punishment of death should be abolished, except for treason and murder; and that, for other felonies, should be substituted hard labor in the public works." His measure lost by a single vote.

Others had at least as much concern for principle as for practice. The death penalty, they said, was a distinctly monarchical punishment; reformation, on the contrary, was compatible with republican ideals. To resist the death penalty, then, was a political gesture. Having seen fellow patriots risk execution for their principled political stand, they viewed it as an obligation not to reproduce the tyranny of British justice in their own legal system.

Others took a theological view. Historian David Rothman wrote in 1971 that Calvinist notions of original sin led the early colonists to believe that some human beings were destined to wickedness. The purpose of punishment, the Puritans said, was retribution—a debased criminal soul could not be reformed. After the Revolution, though, as Calvinist doctrine began to give way to more liberal theologies, a kind of optimism began to take over, according to which a merciful and forgiving God might welcome reformation. Religious language figured large in discussions of the penitentiary—an institution whose name suggests the Christian practice of penitence. Solitude, in the words of eighteenth-century social theorist Jonas Hanway, was "the most humane and effectual means of bringing malefactors … to a right sense of their condition." Another contemporary, John Brewster, said, "It has been recommended, both by the practice and precept of holy men, in all ages, sometimes to retire from scenes of public concourse, for the purpose of communing with our own hearts, and meditating on heaven." Louis P. Masur, a Trinity College professor in American institutions and values, summarizes the attitude: "Solitary confinement served as the operating principle of the institution. In solitude, it was believed, criminals would discover true penitence—considered the crux of Christian selfhood."

The final justification for incarceration rather than execution was related to the theological debates: many citizens of the Early Republic shared a new philosophical conception of human nature. One of the central premises of Enlightenment thought was that social institutions formed character. This model saw human beings not as fundamentally flawed wretches who needed chastisement, but as rational beings, shaped by their environments, and capable of reformation. The right social institutions would produce virtuous citizens; the enlightened leader was therefore obliged to promote virtue, not to admit failure by executing those who strayed from the paths of virtue.

All of these developments in America were informed by theorists working on the same problems in Europe, including Jeremy Bentham and John Howard. The most influential was Cesare Beccaria, an Italian philosopher whose most important work, Dei delitti e delle pene—On Crimes and Punishment—appeared in 1764. The English translation was well known in America. Jefferson recommended it to John Norvell in 1807 as one of the essential works on "the organization of society into civil government." Jefferson several times praised the Italian: "Beccaria and other writers on crimes and punishments, had satisfied the reasonable world of the unrightfulness and inefficacy of the punishment of crimes by death." Legal historian Adam Jay Hirsch summarizes Beccaria's central thesis: "Whereas criminologists had traditionally assumed that deterrence hinged on the severity of the punishment, Beccaria postulated that the certainty of punishment contributed far more to the inhibition of crime." Jefferson said: "The principle of Beccaria is sound. Let the legislators be merciful, but the executors of the law inexorable."

Some continued to believe in the efficacy of the death penalty, and viewed incarceration as coddling criminals: during the debates over execution, the number of hangings increased dramatically. The most substantial problem with locking people up, though, was that early American prisons could be less humane than the death and torture they were meant to replace. Being incarcerated even briefly could be tantamount to execution.

Corruption was rampant; prisoners were expected to bribe their keepers for minimally adequate treatment, and those without money were often allowed to die of neglect. The buildings, too, could prove fatal. Few were purpose-built facilities; many were dilapidated residences that had been quickly fitted with bars and padlocks. Hygiene was appalling—open sewers often ran through the facilities—and rarely were there fresh provisions or clean water. Benjamin Franklin's brother James was imprisoned for concealing the author of a seditious article published in his newspaper, but after a month a doctor persuaded the authorities that his detention had damaged his health. He was released on the condition that he give up publishing his newspaper.

Dangerous settings like these led to calls for more humane houses of detention. Reformer Richard Mead wrote in the 1720s that "Our common Prisons" were afflicted by "the Goal Fever, which is always attended with a Degree of Malignity in proportion to the Closeness and Stench of the Place." He advised the government "to take Care, that all Houses of Confinement should be kept as Airy and Clean, as is consistent with the Use, to which they are designed."

In his State of the Prisons of England and Wales, former sheriff John Howard, offended by the ubiquity of bribery, wrote in 1777, "No Prisoner should be subject to any demand of Fees. The Gaoler should have a salary in lieu of them; and so should the Turnkeys." He was also disturbed by "the gaol-fever, and the small-pox, which I saw prevailing to the destruction of multitudes, not only of felons in their dungeons, but of debtors also."

These calls for decency echoed in the early Republic. Quakers were especially active in ensuring prisoners were kept healthy and treated with dignity. We can see the concern with the humane treatment of malefactors even in our Bill of Rights: the Eighth Amendment stipulates that "excessive bail shall not be required, nor excessive fines imposed, nor cruel and unusual punishments inflicted."

The penitentiary marks progress from the barbaric executions of the earlier eighteenth century, but its story does not have an unambiguously happy ending. What seemed straightforward in the optimistic 1780s proved increasingly complicated as the decades passed. As Jefferson wrote to William Roscoe in 1820, "Beccaria had demonstrated general principles, but practical applications were difficult. Our States are trying them with more or less success." He might have put the emphasis on "less." Prisons quickly became overcrowded, expenses mounted, and taxpayers were unwilling to make convicts' lives more comfortable. High recidivism led many to question whether reformation was possible after all. Worse still, many of the lessons learned in developing an efficient system of incarceration were applied to chattel slaves in the South, who were subjected to the same kind of surveillance and control that jailers had learned to use on criminals: the two systems reinforced each other.

The story of the penitentiary is not over. Benjamin Rush, a signer of the Declaration of Independence, wrote in 1787 that "The design of punishment is said to be,—1st, to reform the person who suffers it,—2dly, to prevent the perpetration of crimes, by exciting terror in the minds of spectators; and,—3dly, to remove those persons from society, who have manifested, by their tempers and crimes, that they are unfit to live in it." Achieving any one of these ends is difficult enough, but achieving all three can seem impossible. Balancing these competing interests—the reformation of the criminal, the prevention of crimes, and the protection of the public—was a challenge facing the founding generation, and vexes us still.

Jack Lynch, author of Becoming Shakespeare: The Unlikely Afterlife That Turned a Provincial Playwright into the Bard (Walker & Co., 2007) is professor of English at Rutgers University. He contributed to the Winter 2011 issue an article on literacy in early America.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Scott Christianson, With Liberty for Some: 500 Years of Imprisonment in America (Boston, 1998).

- H. Bruce Franklin, Prison Literature in America: The Victim as Criminal and Artist, rev. ed. (New York, 1989).

- Adam Jay Hirsch, The Rise of the Penitentiary: Prisons and Punishment in Early America (New Haven and London, 1992).

- Louis P. Masur, "The Revision of the Criminal Law in Post-Revolutionary America." Criminal Justice History 8 (January 1987): 21–36.

- Blake McKelvey, American Prisons: A Study in American Social History prior to 1915 (Montclair, NJ, 1936).