Online Extras

Extra Images

Zoom in on the Slate Tablet

Author Kelso stands inside the excavated 1607 fort at Jamestown, long thought to have washed into the James River.

The palisades and rounded bulwark—cannon emplacement—were re-created on top of the excavated post holes of the 1607 fort.

Danny Schmidt, staff archaeologist at the Jamestown Rediscovery Project, uncovers a mud-wall building foundation inside the fort.

The eastern corner of the 1608 church excavation sits behind a statue of John Smith, an experimental “barracks” in the background.

Preservation Virginia

Danny Schmidt next to the cellar well in which a written-over slate and personalized pipe stems were among the objects found.

Preservation Virginia

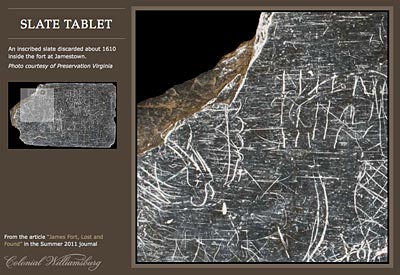

Zoom in on this inscribed slate

An inscribed slate discarded about 1610 inside the fort at Jamestown, to be found almost four hundred years later.

The author next to a 1/4-scale bronze model of the excavated fort, with the tower of the 1647 church standing behind him

James Fort, Lost and Found

by William Kelso

Almost all the archaeologists and historians told me it couldn't be done: find the site of the 1607 James Fort on Jamestown Island. No way. Clearly, they said, the fort site—the place of England's first permanent New World settlement—was long lost, washed away by James River shoreline erosion. The lost theory made perfect sense. After all, the first settlers chose the island to seat the Virginia Company of London colony because the river channel was close enough to the shore to moor their ships to the trees. Since the area near the channel had long eroded away, the conclusion that the fort site went with it was hardly illogical.

Of course, I did not know that when, as a tourist in 1963, I first went to Jamestown Island Historical Park looking for the fort. My goal was to walk where Captain John Smith walked and gain some sort of context for the near-mythological but gruesome Jamestown story I had read—the one where most everyone but Smith was incompetent and chose to die rather than work. That was when a National Park Service ranger told me the "long lost erosion" story. But I also learned that there was a colonial soil layer buried under a fort I did find, the 1861 Confederate earthwork appropriately named Fort Pocahontas. The thought occurred to me at that moment: maybe someday some archaeologist might take a look under there.

That someday came to me thirty years later, after becoming an archaeologist and after a decade of discussions with the landowner, the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. As the 400th anniversary of Jamestown appeared on the horizon, the APVA, now called Preservation Virginia, was ready to consider a plan to find the 1607 James Fort. Two thousand and seven would be a birthday party year for the nation. We all agreed that discovering the lost fort would be the very best birthday present imaginable.

But to be honest, when the first shovel went to earth in 1994, I felt as if I was mostly whistling in the park. The crowd of knowledgeable skeptics almost undermined any confidence that I had. Nevertheless, I told myself, at the very least it was up to someone to prove that the fort site was NOT to be found.

Like any archaeological venture, digging had to start where there appeared to be the best chance for success. Where was that? The one remaining above-ground relic of seventeenth-century Jamestown is a brick church tower. Early records made it clear that the original church was "in the midst" of the fort. It followed that if that tower in any way marked the midst of the fort, then digging between it and the river shore might just intersect the remnants of a fort wall. It would take a dedicated group of experienced archaeologists and field school students that first summer season to prove it.

We did.

On the very first day, removal of eight inches of modern soil revealed an earthen pit that proved to be full of arms, armor, parts of muskets, swords, ammunition bandoleers, ceramics, and coins—all military and old enough to be signs of James Fort. Expansion of the first trench revealed traces of decayed upright logs in a linear trench along the riverbank. There was a good chance that this marked one of the decayed fort walls.

Eureka moment number one. There were more to come.

Records also indicated that the corners of the triangular fort extended out beyond the wall lines to form circular cannon positions known as bulwarks. So, once part of one wall of the triangular enclosure appeared, it made sense to follow it in the hopes of coming to a place where the line changed direction, hopefully in a circular shape. Eventually two of the bulwarks' circles were found—one attached to the river wall.

Eureka moment number two.

The third wall of the triangle remained elusive. Our original guess at the size of the fort, two acres, was an overestimation, leading the excavation astray. It was not until 2003 that a search beneath the Fort Pocahontas earthwork revealed the well-preserved west palisade line.

Eureka moment number three.

Then the north bulwark's junction with the west wall appeared just as predicted. There remained the final litmus test: Were the measurements on the ground going to match the dimensions reported by the secretary of the colony, William Strachey? He said that the east and west curtains, or walls, were one hundred yards long and the river wall 140 yards. Our ground measurements proved to be within a few feet of Strachey's dimensions.

Absolute eureka time.

By 2006, much of the lost fort was found, just in time for the festivities the following year, which included the visits of Queen Elizabeth II and the Duke of Edinburgh, President George W. Bush, Vice President Dick Cheney, Virginia Governor Tim Kaine, and close to 500,000 others. It is impossible to describe just how I felt when I realized that the below-ground fort was basically all there for viewing. But clearly, the standing church tower, the original anchor point guiding our trowels, was not in the midst of the fort. Rarely, but sometimes in archaeology, close enough counts.

Just as the walls were appearing, excavation ten feet inside and along the lines began to expose the remnants of buildings: posthole patterns marking where structures supported by in-the-ground upright timbers once stood. Each of these buildings had clay, pit-like cellars and short life spans. When they fell apart or were pulled down, the open cellars caught the crumbling mud walls. Then refuse was thrown in: arms, armor, coins, and ceramics from circa 1610. Jamestown almost failed that year. With food gone and no perceived hope of resupply, on June 7, 1610, everyone boarded their ships and sailed away from Jamestown.

But not for long. After a thirty-hour trip toward the ocean, they were intercepted by a fleet of supply vessels under the newly appointed governor for life, Lord De La Warre. Evidence that the new governor soon built timber row houses showed up archaeologically along the west wall. These structures appeared to be the first permanent houses in the fort and were erected on cobble footings and brick foundations. Then a timber-lined well was found nearby which served the row houses' occupants, undoubtedly structures fit for the governor and his council. At the same time, it was reported that De La Warre "cleansed the town." The trash and razed mud building debris probably from that operation wound up in cellar pits.

Next excavations could turn closer toward the center of the fort. There, postholes revealed the location of an underground blacksmith shop and bakery and a substantially built central storehouse with an attached well in a cellar. The clay walls of the cellar held a rapidly deposited mass of garbage and trash dumped in after the well water went bad, undoubtedly more of the 1610 De La Warre clean up.

Then in 2010 excavations uncovered remains of Jamestown's substantially built church, the first Protestant church in America, and the church where Pocahontas, chief Powhatan's favored daughter, married tobacco planter John Rolfe. Remains of the church included enormous postholes with impressions of upright timber columns exactly twelve feet apart found near, but slightly southeast of, the center of the fort. The holes defined a rectangular pattern suggesting an overall twenty-four-foot building width and a probable sixty-foot length. The Jamestown church, built in the spring of 1608, was described as "a pretty chapel," with dimensions matching the archaeology.

The discovery of four perfectly aligned graves at the east end of the post pattern left no doubt about the building's identity. These have to be the church's chancel burials, traditionally the place reserved for very high status people.

Despite the revelations of the past seventeen years, the archaeology at James Fort is far from over. Besides uncovering the rest of the 1608 church, there are areas within the fort triangle left unexplored. Potential building sites along the interior street and the palisade extension to the east, probably the area of the five-sided Jamestown that John Smith alluded to in 1608, will be investigated in the years to come. The Civil War fort already partially excavated is also on the agenda for 2011–12—a research contribution to the Civil War sesquicentennial commemoration.

So far, we have found more than 1.5 million artifacts at James Fort. Almost daily, someone asks me to name my favorite. Of course, they are all pieces of a puzzle that breathe life into the otherwise vague and almost mythical documentary Jamestown story. But truth be known, to me there have been certain objects that have proven to evoke more about early life and death at seventeenth-century Jamestown than others. Three things immediately come to mind.

While searching for the elusive west fort palisade in 2003, a single grave aligned with the predicted wall line was discovered. Excavation initially uncovered the outlines of a coffin upon which lay a spear-like object: a captain's leading staff. The burial turned out to be that of a man who died in his middle thirties, presenting the strong possibility that these were the remains of Captain Bartholomew Gosnold, the vice admiral of the first Jamestown fleet, who died in August of 1607 at thirty-six. These facts sparked a closer look at Gosnold's biography. He was the most experienced Atlantic explorer among the 104 first settlers, and he was instrumental in finding the money and securing the charter for the Jamestown venture through family connections. Few historians had recognized the importance of Gosnold before the discovery of these remains. Captain John Smith's passing admission that Gosnold was the mastermind behind the Jamestown venture instantly took on new meaning.

The 1610 De La Warre artifact-rich trash also wound up in the cellar well. One object in particular proved to be a gift from the past that keeps on giving: a five-by-eight-inch discarded slate tablet covered with faint inscriptions: words, symbols, numbers, and drawings of people, plants, and animals. There are layers upon layers of inscriptions, ranging in quality from mostly fragmented to mostly complete.

On one side a line of capital letters, I" EL NEV FSH"I"HT LBMS, and likely a date, 1598, appear written above a strangely self-deprecating English sentence: "I" AM NON OF THE FINEST SORTE." On the opposite side, written in Elizabethan secretary-hand style, is clearly the name Abraham, and perhaps lines making up an accounting ledger, possibly a list of the equipment used or ordered by Abraham Ransacke, a metals refiner at Jamestown in 1608.

Artwork superimposed on the slate includes sketches of three men, a woman, four flowers, two fleurs-de-lis, and four lions on one side, and two men, three birds, and a tree on the reverse. Three of the men are drawn dressed as soldiers, and one appears to be wielding a sword, apparently threatening the woman he holds by the shoulder with his left hand. It is apparent that another and more accomplished artist drew a civilian man wearing a ruff collar, a decorative doublet vest, and "venetians" trousers—all dress usually reserved for the elite.

On one side, the drawings also include four rearing lions, three flowers, and three fleurs-de-lis. The lion is in the "rampant" position, a common symbol on crests and shields. On the opposite side, three fairly detailed pictures of birds of prey appear: what may be a short-legged green heron and an eagle, a sea gull, or even possibly a cahow, a native only to Bermuda, and a palmetto tree.

So, what do these inscriptions tell us so far about life at Jamestown? Are the block letters some schoolboy practicing? Only eleven letters from the twenty-four-letter Elizabethan alphabet are included, so the letters likely do contain a message. Perhaps they are only initials of people. To what end? A Welsh tradition might be a clue. In Wales, it was a custom to put a curse on someone, or the opposite—wishing them good luck—by putting their names or initials on a slate and tossing it into an open well. Sounds plausible if you ignore the fact that the Jamestown slate was found in thick rubbish that was purposely dumped into the already abandoned and partially filled-in cellar above the well.

And who used this slate? It is tempting to suggest the author-artist is William Strachey himself. It was he who wrote about his harrowing hurricane shipwreck on Bermuda, thought to be the source for the story line in Shakespeare's Tempest. Strachey may have arrived at Jamestown with his pocket slate—his "rough draft" notebook—which he had used since 1598 and lost during the aforementioned De La Warre clean-up. Strachey's family coat of arms does include a rampant lion and fleurs-de-lis. Moreover, when he was marooned on Bermuda, he could have sketched the unfamiliar-to-him cahow and the palmetto. In addition, Strachey's hope for inheritance died in 1598 with his indebted father, keeping him practically penniless among his well-off fellow law students at Gray's Inn. His desperate financial straits at that time could explain the date on the slate and the sentence about lacking "finest sorte" status.

The cellar well also held an intriguing group of clay tobacco pipe stems upon which the maker, probably one Robert Cotton, had impressed the names of a number of the major movers and shakers in the Virginia venture: Sir Charles Howard, Lord High Admiral of the English Fleet and Queen Elizabeth's closest courtier; Sir Walter Ralegh, New World explorer and Elizabethan courtier; the Earl of Southampton, Henry Wriothesley, Shakespeare's major patron and top Virginia Company official; Lord De La Warre, Sir Thomas West, major Virginia Company investor and Virginia's first resident governor; Captain Samuel Argall, maritime explorer and lieutenant governor of Virginia; Captain Francis Nelson, admiral of the second Virginia supply fleet; Sir Walter Cope, Virginia Company councilor and London antiquarian; and Robert Cecil, Lord Salisbury, King James's secretary of state, prime mover behind the 1604 peace Treaty of London between England and Spain, and leader of the Virginia Company of investors in 1609.

It is tempting to suggest that Cotton made these pipes as a way to prove to investors that the Jamestown colonists were hard at work trying to produce things that would sell in England. Of course, making money on tobacco pipes turned out to be a pipe dream. But Cotton was heading in the right direction. In the end, growing and exporting tobacco would ensure that Virginia would live on.

Whatever the meaning of the inscribed slate and the named pipes, there can be no doubt that these artifacts are as exciting as finding the proverbial trunk of lost letters in the attic. But these things only have meaning because they were found sealed in the abandoned cellar well at the epicenter of the lost—then found—Jamestown. In fact, that rather crude and fragile English fort site is really my most treasured favorite artifact. From that place eventually grew the British Empire, spreading lasting traditions of democracy, rule of law, private enterprise, and the global English language. Life on a good part of the earth has never been the same.

William M. Kelso is director of archaeological research and interpretation at Historic Jamestowne. This is his first contribution to the journal.