Rare Sheep

From Hog Island and Leicester

text by Ed Crews

photos by Dave Doody

Colonial Virginians didn't care much for sheep. For eating, they preferred pork and beef. For making money, they could do better with tobacco. Plus, sheep required a lot of attention and protection from predators.

Virginians kept sheep from their colony's earliest days and occasionally might enjoy a rack of lamb, but sheep didn't arouse enthusiasm. That changed, gradually, as the colony moved away from tobacco and the Revolution stimulated demand for homegrown wool and meat. But, for a long time in early Virginia, sheep, known to science as the creatures Ovis aries, got little attention. Contemporary visitors described them as "small and mean," "miserable," and "degenerate."

Nobody today applies those terms to the two rare breeds of sheep Colonial Williamsburg keeps in its Historic Area. They're Hog Island sheep and Leicester Longwools, watched closely, well fed, and cared for. They epitomize two schools of eighteenth- century animal husbandry.

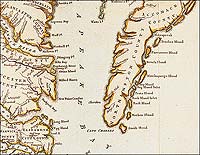

The Hog Island sheep show what a species can become when left alone. They're descended from animals raised decades ago on Hog Island, a 45,000-acre barrier island off Virginia's Eastern Shore in the Atlantic Ocean. The environment made them hardy but relatively small. Mature ewes weigh about 90 pounds; rams about 125. Their fleece typically is white. Hair covers most of each animal's face and legs. Rams and ewes can have horns.

Their origins are dim, but they closely resemble sheep typical of Virginia during the 1700s, according to Marshall Scheetz, a Colonial Williamsburg cooper who has studied the animals. Colonists moved to Hog Island in the 1600s, eventually raising such livestock as pigs, goats, chickens, cows, and sheep. Their settlement town took little space, leaving the animals a large area to roam and to graze. Like the other animals, the sheep got little human attention. Once a year, the colonists rounded up the sheep, and owners marked their animals by notching their ears. Hog Islanders occasionally ate mutton and processed wool locally.

During the 1930s and 1940s, Hog Island life changed. Hurricanes and ocean storms forced people to leave. Most of the sheep went with them. A few left behind flourished with natural forage and no predators. In 1974, the Nature Conservancy, a national nonprofit dedicated to saving wild places, bought the island and considered the options.

"The Nature Conservancy had to decide how Hog Island would be used to best promote their mission," Scheetz said in a thirty-nine-page report written in 2002. "They chose to turn the island into a nature preserve instead of a sheep preserve, because they theorized that a feral population left uncontrolled would reproduce beyond the carrying capacity of their environment, leading to watershed problems and soil erosion. It was believed that 'genetically speaking the stakes were much greater on the natural side of the equation than the feral.'"

Most of the sheep were removed, but about eighteen remained on the island. By a 1978 inspection, their numbers had grown to 100. Another roundup captured all but about eight.

In the late 1970s, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University studied the Hog Island sheep. The school obtained ten rams and twenty ewes for research. Once the study ended, VPI professors sought a home for the animals. George Washington's Birthplace at Pope's Creek took eleven. The park has sent Hog Island sheep to such other historic sites as Gunston Hall, National Colonial Farm, and Mount Vernon. In May 2006, Colonial Williamsburg added three of the animals to its rare breeds preservation program. They came from Mount Vernon and now graze contentedly at Great Hopes Plantation, an exhibition farm north of the Historic Area.

The American Livestock Breeds Conservancy characterizes the status of Hog Island sheep as "critical," meaning that only concentrated and sustained effort can save this type of sheep from extinction.

The Leicester Longwools demonstrate how human involvement can alter a breed's fate. These sheep exist mostly because of the efforts of Englishman Robert Bakewell.

Bakewell was born in 1725 at Dishley, a farm in Leicestershire. He belonged to a group of pioneering eighteenth-century men who wanted to use scientific methods to boost agricultural productivity. Bakewell set out to create a breed of sheep that would mature quickly and provide substantial amounts of meat and wool. He carefully selected and bred animals that exhibited those qualities. Today, this seems commonsensical. In the 1700s, it was revolutionary. Bakewell's approach worked and secured him a place in history.

"After the breed became popular, others followed Bakewell's example and began to set standards for other breeds," said Elaine Shirley, Colonial Williamsburg's manager of rare breeds.

Leicester Longwools gained international fame and rock-star-like celebrity. George Wash ington took an interest in the breed and kept some at Mount Vernon. Bakewell took one of his sheep, Two Pounder, to fairs and charged admission to see him. Two Pounder's portrait was painted. Bakewell leased his rams for stud services.

Leicester Longwools became the bedrock of the Australian and New Zealand sheep industry. A measure of their success is the names they acquired: Bakewell Leicesters, Dishley Leicesters, New Leicesters, and English Leicesters. Another measure is the crossbreeds derived from them: Bluefaced Leicesters, Hexham Leicesters, and Border Leicesters.

Nevertheless, the Leicester Longwools, like aging rock stars, lost their cachet, Shirley said, their popularity fading as newer breeds arose that produced more wool and better meat. By the 1960s, Bakewell's sheep were in deep decline.

Knowing of the breed's importance in the 1700s, Colonial Williamsburg acquired Leicester Longwools in the early 1980s. Diligent searching found one lamb in the United States, a ram that came to Williamsburg and was named Willoughby. In 1988, vandals killed him. Donors reacted by paying for a replacement. Study led to the discovery of a source of Leicester Longwools in Australia.

"We learned that we needed to talk to Ivan Heazlewood from Tasmania, Australia. He is an expert on breeding Leicester Longwools. So we contacted him," Shirley said. "We discovered that he'd written a book on the breed and that his grandfather had brought some of these sheep to Tasmania in the 1870s. Ivan had grown up with Leicesters and wanted to reestablish the breed in the United States."

In 1990, with Heazlewood's help, eight ewes, six lambs, and one ram arrived in Williamsburg. Guests, especially children, are drawn to the Leicester Longwools.

"We do a lot with the sheep," Shirley said. "For example, we shear them in front of the public. We also have the ewes give birth in front of the public. People are fascinated by this. At times, we'll have hundreds of people watching. With this sort of visitor interest, the Leicesters Longwools are an important part of our educational efforts."

Ed Crews, a Richmond-based writer, contributed to the spring 2007 journal an article on Colonial Williamsburg's American Cream horses.