Colonial Williamsburg

An Artifact of Popular Culture

by Christopher Geist

In board games, bodice rippers, water glasses, commemorative plates and more, Colonial Williamsburg has become part of America's popular culture.

Actor Jack Lord walked in illustrious footsteps when, portraying fictional planter John Fry in Williamsburg—The Story of a Patriot, he strolled through the turmoil and unrest of the 1770s city. Yes, of course, George Washington's, and Patrick Henry's, and Thomas Jefferson's. But also Cary Grant's. Seventeen years before The Patriot, as Lord's 1957 film is often called, Grant had been in town to portray Matthew Howard in The Howards of Virginia. Grant's movie was feature length, so the story was the more detailed and complex of the two. Still, there are similarities in the productions, not the least of which is the use of restored Colonial Williamsburg as a movie set.

Both films include sequences in the Governor's Palace, the Capitol, and the Apollo Room of the Raleigh Tavern, and feature appearances by Jefferson and Washington. Both present the climactic moment when the Virginians direct Richard Henry Lee to return to Philadelphia to move for "independency" in Congress, and order the king's standard hauled down from the Capitol's cupola. And in both movies the observant viewer notices that Colonial Williamsburg was a work in progress. Try as he might, neither director could prevent the camera from glimpsing anachronisms—here a bus, there a too-recent building.

Williamsburg's restoration has progressed since The Patriot began what, at this writing, is a forty-nine-year run at the Visitor Center, and the director of the next feature film produced in the Historic Area won't have to shoot around that problem. Wherever the cinematographer points his lens, it will capture a town that has become the consummate image of an eighteenth-century Virginia city, an artifact of American popular culture.

Popular culture artifacts are widely recognized and accepted by the general public as representing cultural importance and shared meanings. Like most aspects of popular culture, such artifacts are frequently commercialized, appear in the mass media, are generally understood and available to most members of the culture, and have the power to entertain, as well as to enlighten and educate. Though popular culture is generally associated with leisure time activities and frequently involves mass production and consumerism, it does not follow that the underlying meaning is trivial or easily forgotten. On the contrary, such popular culture artifacts as Colonial Williamsburg help to shape our understanding of our culture and its history.

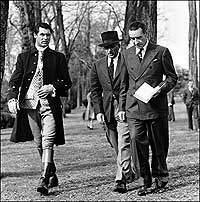

Richard Thomas, who would grow to become John-Boy Walton, poses beside a co-character in a 1962 episode of 1,2,3 Go!.

Why is Colonial Williamsburg so frequently represented in the products of popular culture? In most instances, the creators of popular entertainments and consumer goods, as well as the consumers who patronize them, are drawn to the most conspicuous example in any given class of items. Colonial Williamsburg presents a generally accepted popular vision of colonial America, and it is the most prominent example of a living history museum village. Its presence is ubiquitous in popular culture materials, and it became the popular standard in the field of living history.

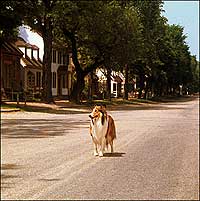

Television is our most pervasive and popular medium, and Colonial Williamsburg has had a presence almost from the start. Will Rogers Jr.'s Good Morning show, and Wide, Wide World both filmed segments in the restored city in 1956. Ten-year-old Richard Thomas, better known as John-Boy Walton, starred in an episode of the children's program 1, 2, 3, Go! from the Historic Area in 1962. Lassie visited in 1966, in one segment of a series of episodes in which she was lost and wandered the country as her master searched for her. The fearless canine was falsely accused of being a dangerous dog by a Virginia turkey farmer, but was exonerated with the help of a sympathetic attorney portrayed by MacDonald Carey. Alistair Cooke spoke from the House of Burgesses in scenes from his personal history of America broadcast in 1972 and 1973. Most network news programs have recorded segments at Colonial Williamsburg, including The Today Show and Good Morning, America. The History Channel and PBS have taped in the Historic Area, sometimes using its streets and buildings as stand-ins for such other colonial cities as Philadelphia and Boston. Producer Ken Burns used the town as a set in his documentaries on Jefferson, and Lewis and Clark.

Colonial Williamsburg has been the setting for Christmas specials. Two memorable examples still available for home video viewing are Perry Como's Early American Christmas from 1978 and Al Roker's Colonial Christmas in 2000. John Wayne was a guest on the Como program. Roker's program appeared on the Food Channel and included behind-the-scenes visits to the Williamsburg Inn's kitchen and the costume design center. Williamsburg employees appeared in both productions. Interpreter Greg James turned in a fine performance for Roker, strolling down Duke of Gloucester Street in character, singing "O Come, All Ye Faithful."

George Washington, 1984 miniseries with a 1986 sequel, filmed in the Historic Area. The show starred Barry Bostwick in the title role and Patty Duke as Martha Washington. The Wythe House, Governor's Palace and gardens, the Capitol, Raleigh Tavern, and city streets were part of the production. Its version of Henry's "Caesar-Brutus" speech is so similar to the one in The Patriot it seems almost a homage. Williamsburg interpreters appeared as extras. One, Christy Hill, wore a green and gold striped gown with a brown bodice trimmed in gold braid and white lace initially intended for Patty Duke.

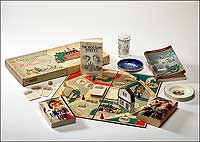

Popular culture's material realm includes, among other items, vacation souvenirs, memorabilia, and collectibles. Americans fill their homes with such items, helping to sustain pleasant memories of family journeys, and to announce their hobbies, interests, and fascination with special places. Collectors of Williamsburg paraphernalia commonly assemble such items as shot glasses, tumblers, ashtrays, hot pads and dish towels, elaborately illustrated calendars, matchbooks, refrigerator magnets, postcards, miniatures of Colonial Williamsburg buildings, toy soldiers and colonial citizens, cocked hats, coloring books, and bumper stickers. Most of these items are officially sanctioned and licensed by Colonial Williamsburg, but many are not.

Some people collect anything and everything they can find associated with Williamsburg, and others focus on a particular category. An example of the latter is The Cat's Meow Village group of Colonial Williamsburg's historic buildings produced in 1994. The Cat's Meow Village consists of two-dimensional wooden replicas of the facades of historic structures from throughout the United States, each with the black silhouette of a cat sitting somewhere on the building. The Colonial Williamsburg collection includes the Governor's Palace, Capitol, Courthouse, Bruton Parish Church, and the Magazine, along with most of the trade shops. Another purveyor of collectibles, Bing & Grondahl's Copenhagen Porcelain, featured the Governor's Palace as its initial number in its annual Christmas in America Collection series of commemorative plates begun in 1986.

There are board games based on the colonial town. Early versions often may be had at antique stores. My own copy of The Great Game of Visiting Williamsburg bears a 1958 copyright and was discovered in a shop in northern Ohio. Somewhat like Parcheesi, players circle the board from four stations at The Capitol, The Magazine, The Governor's Palace, or the Gaol. Along the way they visit such places as Robertson's Windmill, the Raleigh Tavern, the Wren Building, and trade shops, which offer penalties or bonus moves. The Blacksmith Shop sends a player ahead ten spaces, but the Pillory and Stocks send a player back to the starting site. Players draw Chance Cards from time to time that send them to one of the town's locations and include a bit of history. The Apothecary Shop card, for example, says, "In colonial days the Apothecary and Doctor supplied the housewife with herbs, spices and medicines. He also performed operations. An account book in the doctor's office tells us that Patrick Henry bought medicine in this shop."

Fiction, especially genre fiction, is an important part of American popular culture, and Colonial Williamsburg is an inviting backdrop to many a novel. Two examples of romances set in Williamsburg illustrate use of the restored city. Though both books are set in the 1770s, the careful reader understands that the landscape described is not an authentic eighteenth-century city. The modern restoration informed the author's vision, and there are anachronisms indicating that the past is seen through modern eyes. Lynne Hayworth's Autumn Flame, published by Zebra Books in 2001, details the adventures of Lucy Graves, a London pickpocket transported to Virginia as an indentured servant. Her travails in romance and revolution take place throughout Williamsburg and the countryside. Long segments play out on a plantation that is clearly based on Carter's Grove. Convincing details of costume, architecture, modes of travel, foodways, and indentured servants' daily lives build a story which rings true to the era it portrays.

Less satisfying as history is Corinne Everett's Loving Lily, Zebra, 2001. Lily Walters, described as an "ardent Patriot," becomes involved with her brother's intrigues with Virginia rebels in the days before the Revolution. The book is filled with twentieth-century language and details, not the least of which is Lily's occupation in Williamsburg. She is a florist with a shop based on modern examples, selling floral arrangements for weddings, family gatherings, and to decorate businesses. A good many of the novel's actions revolve around Lily's profession. No such florists existed in the 1770s. Lily's story ends just as does Lucy's—she lives happily ever after with her romantic hero.

More interesting are novels set, at least in part, in restored Williamsburg. Taffy Cannon's Guns and Roses, published by Perseverance Press in 2000, is a contemporary murder mystery involving a bus tour group led by Roxanne Prescott, former police-woman turned guide. Murder and mayhem are scattered throughout the Historic Area and countryside, including scenes at Carter's Grove, Market Square Tavern, the Magazine, and up and down Duke of Gloucester Street. Roxanne nabs the killer by the end of the novel.

Combining the past and present, M. G. McManus's romance trilogy Nicholson Street, Francis Street, and Duke of Gloucester Street, done by Colonial Publishing in 1986, 1988, and 1989, relate the adventures of archaeologist Charles Dalton, who stumbles on a portal to the past. Action meanders between the 1770s and the 1980s, letting the author comment on the details of the restoration while speculating on how a modern American would react to the unrest preceding the Revolution. Dalton interacts with Jefferson, Washington, George Wythe, and others. He brings eighteenth-century characters back to the 1980s, a device offering an opportunity to speculate on how colonial Virginians would react to modern Williamsburg and such phenomena as pizzas, alarm clocks, and televisions. The author's conceit works because Colonial Williamsburg becomes the main character.

In 1991, Felicity Merriman debuted as a perky nine-year-old Williamsburg resident on the eve of the American Revolution."

No popular culture phenomenon connected with Colonial Williamsburg can compete with Felicity Merriman, "a spunky, spritely nine-year-old girl" living in Williamsburg on the eve of the Revolution. Felicity was the first doll in the American Girls Collection issued by Pleasant Company in 1991. Combining popular culture genres, Pleasant Company marketed the eighteen-inch Felicity doll along with six books targeted at girls aged seven to twelve. There were colonial costumes for the doll and for the girls who owned her. Accessories included a Felicity-sized Windsor Writing Chair; her guitar; a tilt-top tea table and matching chairs; a chocolate set with pot, cups, and napkins; a bedroom suite with tall-post bed and tester, dressing table, clothes press, and bed warmer; as well as colonial toys and other eighteenth-century accouterments. Felicity's owners could purchase appropriate garb to wear as they play with their dolls, including a Rose Garden Gown, a Colonial School Outfit, and a Felicity Night Shift and Cap. The books recount Felicity's adventures as she helps persuade a runaway apprentice to return to his job, learns about slavery, helps break a horse, and experiences firsthand the growing Revolutionary ferment of Williamsburg in the 1770s.

Has Felicity had any impact on girls' understanding of Williamsburg's place in American history? Ask Dale Smoot, Colonial Williamsburg military historian and interpreter for more than sixteen years. In the spring of 2005, while conducting family groups on tours of the Magazine, Smoot began an informal survey, asking each group, "Has anyone here heard of the Powder Incident?"

Several girls, about eight to twelve, raised their hands, but almost never did young boys. Governor Dunmore's decision to send Royal marines to the Magazine in the middle of the night April 21, 1775, to take the colony's gunpowder is not so well known as a similar incident a few days before at Lexington and Concord. But these young girls knew about it though the boys did not. "How did you learn about Governor Dunmore's actions?" Smoot asked. "Felicity was there!" came the reply.

Sometimes for the better, and other times for the worse, the products of popular culture help shape and inform our understanding of the world around us, including our history.

Christopher Geist, professor emeritus at Ohio's Bowling Green State University, contributed a story to the winter 2006 journal about hurricanes.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Christopher Geist, "Living History Villages as Popular Entertainments," New England Journal of History, 51, no.2 (Fall 1994): 57–66

- The Journal of Popular Culture is available in most larger libraries and offers many insights into the nature and meaning of popular culture materials

- Russel B. Nye, The Unembarrassed Muse: The Popular Arts in America (New York, 1970)