Time for the Royals

Tompion's Clock

text by Graham Hood

photos by Hans Lorenz

Soon after the new capital of His Majesty's Colony of Virginia was founded and named in his honor in 1699, King William III took delivery of a new clock in London. It was no ordinary timepiece, even in the days when any timepiece was far from ordinary, for it towered more than ten feet and was spectacularly ornate. It was a creation of polished burl walnut, gilt ornaments, baroque finials, and silvered dial, fronting an advanced mechanism, all surmounted by a martial, female figure of gilt bronze.

It was fit for a king, though it ticked so loudly in his bedchamber at Hampton Court Palace that the misshapen, asthmatic monarch sacrificed its splendors to the cause of sleep. That, at least, is how a below-stairs tradition has garnished its history. After William's death a couple of years later, the clock ticked gracefully away in royal apartments for more than a century and a half until Queen Victoria presented it to her cousin, the second duke of Cambridge. Upon his death in 1904 it was sold at auction in London for a pittance.

It sold again a few years later, also at auction, and turned a nice profit, though in our world of glutted prices the sale figure now sounds ludicrously low. From there it went into a private collection, and thence to a swanky Bond Street dealer. At that point the "Record Clock," as it was then inscrutably called, undertook its first transatlantic voyage. It had attracted the attention of the American collector Francis P. Garvan, who bought it, shipped it to the United States, and lent it to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. He sold it in 1934.

I am struck by Garvan's ownership, though it is probably of no consequence to most readers, for I spent several happy years working with the first-rate collection of American decorative arts that he assembled and presented to Yale University in honor of his wife, Mabel Brady Garvan.

Twenty years later, the then-curator of Colonial Williamsburg, John M. Graham, heard from an English collector and author, and sometime dealer-agent, that the clock might be again for sale. It was thought to be perfect for the Governor's Palace. Had it not, after all, been made for one of King William's palaces? It would be expensive—£10,000, a mere bagatelle by today's standards—and there might be problems with the export license. There was none. Such matters never deterred Graham; they seem to have acted as a spur to his collector's instincts, which ran very deep. Over many governmental and private objections in England, regardless of the jeremiads and lamentations sent in the form of letters to the Times, Colonial Williamsburg bought the clock and subjected it to its second transatlantic journey. Despite widespread recognition that the clock was an English national treasure, the export license was obtained on the technicality that the clock had left England's shores once before.

In Williamsburg, it was placed in the Upper Middle Room of the Palace, where, proudly described as the "Tompion Clock" after the horologist who had made its works, it gathered attention, fame, and, slowly, notoriety. Younger and more literal-minded curators and collectors began to question how the clock could possibly be appropriate for the "authentic" Governor's Palace in Williamsburg when it had been made for the governor's royal master in London and for a royal palace there. It was removed from that setting in the early 1970s, to re-emerge, resplendent as ever, in the "Masterworks Gallery" of the new DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Gallery in 1985, where it has stood since, one of Colonial Williamsburg's greatest treasures.

Is it the most important piece of early English furniture in America? Perhaps. It is certainly one of them. And why is it called the "Tompion Clock," when that craftsman made only a small fraction of the great work of art you see?

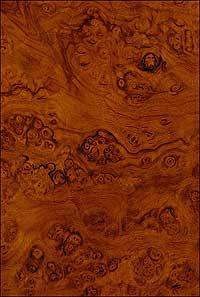

What you do see has commanding presence: tall, rich, elaborate. It is more like the classical furniture of Louis XIV's France—amazing in its complexity and virtuosity—than typical English furniture of the period. This need not surprise us, for French émigré craftsmen abounded in London at this time, refugees from Louis's oppression of his Protestant subjects. The clock's case is a triumphant conjunction of highly figured burl walnut, boldly segmented and clearly defined with crisp moldings, and cast gilt-metal elements that accentuate the transitions and highlight the main section, like groups of instruments in a musical ensemble providing support and counterpoint to the principal themes.

Reading these metal elements from the base of the clock—the black-painted sub-base is a modern, protective addition—upward to its summit, we see bold, baroque scrolls curving into the corners, linked by deeply modeled swags of flowers and leaves, in the middle of which two cherubs hug. Exactly two-thirds of the way up the main case the scrolls reappear, now closer together and leading the eyes outward as firmly as the lower scrolls led the eyes in. Lovely little pieces of sculpture, they mark the transition between the long lower section and the detachable "hood," which surrounds and protects the works and is the culmination of this highly decorative piece. Identical scrolls and swags at the base and the upper scrolls are seen on another royal clock, made later for Prince George of Denmark, husband of Queen Anne.

This lower section—for readers who've been tempted to see what's behind the long door in the case, but never have—provides space for the long pendulum to swing and for the heavy clock weights to descend with gravity, pulling the wires which activate the mechanisms. "Rewinding" the clock pulls these weights back up.

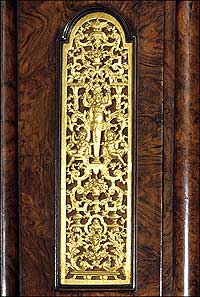

The scrolls appear again at the apex, reduced in size and substance, and now placed horizontally. They lead our eyes to the little plinth supporting the gilt female figure, a perfect spot for the pierced, gilt-metal cipher of the intended owner, His Majesty. In contrast to the lower section, where the walnut figuring dominates, the upper section glitters with gold and silver, as befits a monarch. Intricately worked areas of pierced relief designs—horizontal and vertical panels backed with silk—and the triangular corner spandrels on the face all convey a sense of sophistication and richness. These relief panels serve an extra purpose. The wood behind them has been cut away to allow the sound of the bell that strikes the hours to emerge.

With such a large object one might expect to find that the detail is also broadly conceived—but not with this clock. The elaborate designs are intricate, and give the impression of being larger in scale. They are superb examples of the French baroque-inspired designs by the Dutchman Daniel Marot. Acting as "designer-general" to William of Orange, Marot was responsible for the royal palace at Het Loo, then followed William to England in 1694 and worked at Hampton Court Palace. His royal patronage made him popular, and his imaginative designs, published in book form, influenced English craftsmen for years.

At the summit of this towering work of art stands a gilt-bronze figure of a female deity, clad in armor and holding a spear and a shield. Four grand baroque gilt finials, ornamented with silvered swags, act as sentinels guarding the inclines and platform on which she stands in vigilant but easy stance. Often misidentified as Britannia, the figure is Minerva, goddess of war, defensive, that is, not aggressive like Mars, and of wisdom—attributes with which William may well have congratulated himself he was well endowed. Minerva is said to have leaped forth, mature and fully armed, from the brow of her father, Jupiter. Carrying on his family's implacable opposition to the imperial expansion of the Catholic Louis XIV, the Protestant William might have imagined that the same fate had been reserved for him. Minerva also presided over the useful and peaceful arts of men and women. All monarchs, even bellicose ones, like to be flattered that they are peace loving at heart.

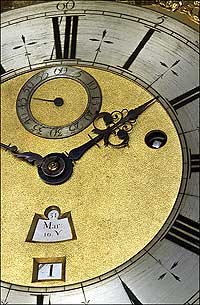

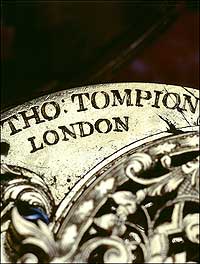

Readers who are used to looking at antique furniture, including tall-case clocks, may be surprised that the dial of this clock lacks the customary identifying inscription, telling who made it and where. In fact, the dial is inscribed with the maker's name and the place where he worked, but it is partially hidden by the gilt molding around the face, and to a person of normal height it is not visible. It states simply THO. TOMPION LONDINI FECIT—Thomas Tompion of London made it. It is only partly visible because for Tompion to have engraved it boldly within the ring of numbers, as was the custom, would have struck his monarch as presumptuous, especially for a commoner, even if Tompion was no ordinary commoner.

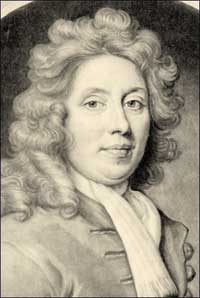

Born in Bedfordshire in 1639, Tompion came from a line of blacksmiths and farriers. He presumably began work at that trade, for he was twenty-five before he was apprenticed to a clockmaker in London. By 1674 he had moved to the Dial and Three Crowns at Whitefriars and Fleet Street, where he worked for the rest of his life. That year he met Dr. Robert Hooke, physicist, curator of experiments for the Royal Society, and professor of geometry at Gresham's College. Hooke had already made remarkable discoveries and original observations, had invented the spiral spring for the balance of watches, and showed that gravity could be measured by utilizing the motion of a pendulum. An irritable polymath, he probably contributed much to Tompion's education. The tradesman impressed the professor in return. He was commissioned to construct an extremely accurate quadrant, which he did to the scientist's complete satisfaction. Through Hooke, Tompion was introduced to King Charles II, who in 1676 ordered from him the first clocks for the Royal Observatory at Greenwich.

Tompion became the first clockmaker in England to apply the spiral spring balance to watches, with such success that his patrons soon included the English and the French royal families. By the time he turned to our tall-case clock, he had patented an escapement with a horizontal wheel, created a clock that distinguished between solar time and mean time—an equation clock, which remains in the royal collection—and devised a clock driven by mainsprings that struck the hours and the quarters. The latter needed to be wound only once a year. Such was his fame by 1700 that a London newspaper announced he was making a clock for St. Paul's Cathedral, still under construction, that "is said will go one hundred years without winding up." Of this indefatigable timekeeper there is no further mention. In conjunction with Hooke again, Tompion experimented with barometers and made one of the first, still at Hampton Court Palace.

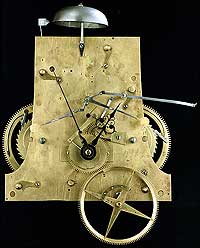

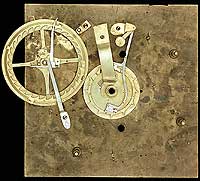

Returning to our redoubtable clock, you may be surprised to learn that all we have looked at thus far was the product of workshops other than Tompion's—even though he got, and still gets, the credit for the whole ensemble. The case, made of oak and veneered with walnut, was the product of an unknown cabinetmaker and joiner's shop. The relief elements were cast and fire-gilded by metalworkers in another unknown shop. The large figure of Minerva may have been cast in yet another shop, and the engraving on the dials probably came from another group, specialists in that genre. But the works—unadorned, fastidiously precise, meticulously functional—are undoubtedly by Tompion.

These works consist of a two-train striking movement, which lasts for three months on a single winding. There is a perpetual calendar that makes allowance for the leap year. Below the numeral XII on the inner dial is a silvered seconds ring. Behind two apertures above the VI are silvered dials that tell the month, above, and the date, below. The upper aperture also contains the signs of the zodiac and the number of the day in the month that the sun enters that constellation. Crosses engraved on the dial, between Roman numerals for the hours, show the position of the hour hand at the half-hour, and tiny crosses on the outer, minutes ring, defined with Arabic numerals, indicate the half-quarter hours. Barely visible today are engraved arabesques on the "ground" plate, beyond the 15, 45, and 60 minutes numbers.

On the inner dial, between the II and III numbers on the right and IX and X on the left, are round, shuttered apertures for inserting the key to wind the mechanisms. A little bolt is designed to open these shutters and at the same time to activate the "maintaining power," which keeps the clock running for three minutes while the key is turned to raise the pendant weights. After three minutes the maintaining power is released and the shutters, with a final virtuoso flourish, close automatically.

In the early 1680s Tompion started to number his products. He made eighteen to twenty tall-case and bracket clocks a year during a thirty-five-year career, and more than 150 silver and gold pocket watches each year—a prodigious output. His work was expensive and exclusive, the watches a gleam in many a pickpocket's eyes, as contemporary "Lost and Found" notices clearly show. It never occurred to me that a Virginian of that time would be up to the level of such an upscale consumer item until I saw the gold pocket watch that "King" Carter had owned, now on display at the Carter family museum at Christ Church, Lancaster County. A rich and heavy object, it says more about the social posture and ambition of that man than almost anything else I know.

So it was with surpassing interest that one day I read a letter from Sacramento telling us that another Carter family pocket watch by Tompion had survived. And it was most generously being offered to Colonial Williamsburg as a gift. What a fantastic complement to the great clock, should it prove right. It did. According to family tradition it had belonged to "King" Carter's grandson, also named Robert, who had lived in Williamsburg and at Nomini Hall in the northern neck of Virginia in the second half of the eighteenth century. Though it had been repaired and had had some parts replaced, compromising it from the strict collector's point of view, its repairs made it more interesting from ours. The gold outer cases bear the hallmarks for 1769, though the works are numbered 4215, showing that they were made about 1708. The later date may well have been when Robert Carter acquired it. Inside the cases are three rare "watch papers" from Virginia jewelers, showing a sequence of cleaning and/or repairs in the 1830s. These obviously support the family tradition.

As ornate within as the clock is austerely plain, the watch is a marvelous example of the treasured world of such sumptuous possessions. Gold and silver, chased and engraved, decorative and functional, the precious works, designed to be seen easily, explain why watches were among the most costly items in personal inventories of the time.

Conservators and horologists today are amazed at how little wear Tompion's mechanisms show, especially those that have been rarely moved and are presumed to have been kept going for most of their three hundred years. They were, indeed, brilliantly made. When the great craftsman died at the age of seventy-four, his fame was such that he was deemed worthy of burial in Westminster Abbey. For a farrier's son, that was not bad.

Graham Hood, Colonial Williamsburg's vice president for collections and museums and Carlisle H. Humelsine Curator until his retirement in December 1997, writes from his home beside the Chesapeake Bay. He contributed to the winter 2003-2004 journal "Lure of the Old."