The Colonial Revival

The Past That Never Dies

by Mary Miley Theobald

The past is never dead. It isn’t even past.

—William Faulkner

Courtesy of Su Carter

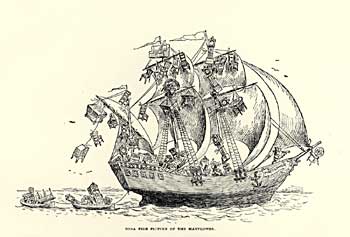

At the peak of the Colonial Revival, antiques that had arrived on the Mayflower seemed so common that the ship must have been awash in furniture, as suggested by this F. Opper cartoon in Bill Nye’s 1894 History of the United States.

Preservation feaver swept America in the 1920s. Virginia, with more colonial buildings than most states, was hard hit. Private individuals and preservation societies snapped up derelict plantation homes and restored and furnished them for personal use or to open to the public. In Virginia, Monticello, Stratford Hall, Montpelier, Oak Hill, Brandon, Kenmore, Ampthill, Carter’s Grove, and dozens more were saved from ruin. Creating museums from historic buildings became a preferred philanthropy for the wealthy: in Michigan, Henry Ford started Greenfield Village; in Delaware, the DuPonts began transforming Winterthur inside and out. And John D. Rockefeller Jr. launched the largest single preservation project the country had seen: Colonial Williamsburg.

Symptoms of the preservation epidemic had begun to appear as early as the 1840s. “Fashion has taken up antiquity,” wrote a member of the American Antiquarian Society in 1842. “Old pictures, old furniture, old plate and even old books which have heretofore suffered neglect . . . are now sought with eagerness as necessary adjuncts of style.” New York’s Metropolitan Museum, which had validated the collecting impulse in 1909 with the first exhibit devoted to American furniture, opened in 1924 an American Wing with period rooms full of American antiques. By the Roaring Twenties, collecting had transcended objects. For those who could afford it, an antique house—restored, modernized, and appropriately furnished—became the ultimate fashion statement.

Historic preservation formed the core of the Colonial Revival, a social and stylistic mindset that peaked during the 1920s. At its start, the Colonial Revival was a social movement that looked to a romanticized past for inspiration and answers to modern problems. When architects hijacked the movement in the 1880s, the focal point became the home. The style has dominated the American landscape since, sometimes sharing the scene with other fashions but never shrinking far into the distance.

Historians, architects, and curators are interested in the Colonial Revival phenomenon. Most date its start to the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition in 1876. Thus an exhibition celebrating the miracles of modern industry launched a movement glorifying the past. Its most popular attraction was Machinery Hall, with the latest technological wonders—the typewriter, the telephone, and the refrigerated railroad car. But the show marked the nation’s one-hundredth birthday, and it was in the city deemed sacred for its association with the Declaration of Independence. The thoughts of the ten million people who visited the fair turned to the past.

Colonial Williamsburg

Wealthy Archibald and Molly McCrea, pictured in 1936, had the means to indulge themselves in all things colonial, including the restoration of the sprawling Carter’s Grove mansion.

The 1870s were troubled. Hard on the heels of Civil War carnage and Reconstruction turmoil came economic depression. Rampant corruption in Washington outraged decent citizens. Striking union workers, Chinese laborers, and emancipated African Americans suffered violent suppression. Custer rode into the valley of the Little Bighorn River.

By the 1880s and 1890s, boatloads of immigrants docked in northern ports, immigrants from eastern and southern Europe whose religions and traditions were vastly different from most native-born Americans’. Industrialization and urban growth threatened agrarian patterns. The European cauldron of revolutions, riots, and anarchist uprisings was spilling onto United States shores. “The influx of foreign ideas utterly at variance with those held by the men who gave us the Republic, threaten, and unless checked, may shake the foundations” of the country, wrote R. T. H. Halsey, a leader of the Colonial Revival movement. To Americans descended of earlier stock, the real America was under siege.

Unsettled times often encourage people to turn to the past. Americans of the late nineteenth century had only to look back one hundred years to see an era that by comparison looked idyllic: a Golden Age of American values, when heroic pioneers sustained their families through honest labor and patriotic farmers fought for freedom beside selfless Founding Fathers. The vision was not so much inaccurate—there were heroic pioneers and selfless Founding Fathers—as it was incomplete and romanticized. But it was a vision widely shared. People pined for good old days when life was simple, friendships true, and everyone lived in rooms full of Queen Anne furniture.

In the public’s mind, America’s Golden Age stretched from the day the Pilgrims set foot on Plymouth Rock—never mind the earlier settlement at Jamestown; this was a northern vision—to the death of the last two Founding Fathers in 1826. People referred to the period as “colonial” though it stretched fifty years past the nation’s birth. So too with furniture: Federal, Heppelwhite, and Sheraton pieces made in the early 1800s were considered as colonial as William and Mary or Chippendale.

Reviving all things colonial seemed the obvious antidote to the nation’s ills. By preserving, exhibiting, collecting, and reproducing the colonial, Americans would be inspired to higher degrees of patriotism. Thomas Jefferson agreed. During the last year of his life he wrote, “Small things may perhaps, like the relics of saints, help to nourish our devotion to this holy bond of our Union.” By the 1890s the Colonial Revival dominated the northeastern seaboard and was spreading south and west. The flood of immigrants had become a tidal wave. Americans everywhere gloried in their heritage even as they worried about its endurance.

The movement’s strongest and earliest proponents were, not surprisingly, men and women whose pedigrees stretched to colonial days. These were people whose ancestors led the country and who were leaders themselves, but whose dominance of the political, economic, and social scenes was waning. Genealogical societies sprang up like crocuses in February as scions of colonial families flaunted their superiority over recent arrivals. Heritage groups were founded: the Sons of the Revolution in 1883, the Sons of the American Revolution in 1889, and the Daughters of the American Revolution in 1890, when the Sons rejected female members. Following quickly were the National Society of Colonial Dames, the Colonial Dames of America, the General Society of Colonial Wars, the Children of the American Revolution, the Society of Mayflower Descendants, and three dozen others, most now defunct.

Dave Doody

Preparing for a soirée in the ostentatiously Colonial Revival Carter’s Grove dining room, Mistress Molly McCrea, interpreted by Sandy Holsten, directs maid Edmonia Washington, portrayed by Jean Mitchell.

Membership in these exclusive clubs stressed blood over money, good breeding over self-made fortunes, old families over upstarts. Some joked that ancestor worship had become the new religion.

After Chicago’s Columbian Exposition of 1893, which celebrated, a year late, the 400th anniversary of Columbus’s discovery of America, colonial was the undisputed national style. At the fair, the eastern states’ pavilions vied with one another for colonial ambience. Pennsylvania re-created Independence Hall, Massachusetts the John Hancock House, Connecticut and New Jersey reproduced rooms where Washington slept, and New York displayed such Washington relics as a scrap of Martha’s wedding gown. Virginia trumped them with a re-creation of Washington’s home, a Mount Vernon complete with portraits and furniture resembling the originals. Twenty million Americans took the message home.

Not everyone could boast bloodlines back to the colonists, but most Americans could, and did, participate in the Colonial Revival. People read histories of the Founding Fathers by authors like Henry Adams, and historical novels by Ellen Glasgow, Maurice Thompson, Paul Leicester Ford, and Mary Johnston that espoused the superior values of the colonial era. Women dressed in colonial garb and attended Martha Washington tea parties. Contemporary clothing fashions borrowed from the colonial: quilted petticoats, mock pannier skirts pulled up on the sides, Empire-style high waists, and mobcaps for the women; and waistcoats for the men. People searched their attics and barns for antiques, or pursued them through the countryside like foxhunters after their quarry. Furniture manufacturers adapted colonial-style furniture to modern ceiling heights and room sizes and mass-produced it.

Architects began to yield to Colonial Revival influences in the 1870s, designing colonial-style homes for pocketbooks large and small. The plain rectangular shape and uncomplicated gable or hipped roof were easy to build; wood was cheap and plentiful.

Colonial was not only the most fashionable style; it was the most affordable. This unbeatable combination spread from New England to the southern and western states. In Virginia, leading architects like Duncan Lee and William Lawrence Bottomley designed many a house patterned on the great Tidewater plantations.

There was the notion that architecture and home furnishings could shape character, an idea called “associationism.” Parents who wanted to raise children with noble colonial virtues—honesty, sincerity, strength, and courage—had better bring them up in a colonial-style house surrounded by Chippendale furniture and spinning wheels. “Luxurious surroundings . . . suggest and induce idleness,” one architect said, while “chasteness and restraint in form, simple but artistic materials are equally expressive of the character of the people who use them.” A furniture manufacturer played to this belief in its 1900 advertisement for an Empire-style sofa. “There is nothing else that can more adequately portray the pure ideas of Puritan life. . . . Can you conceive of the influence of such a piece in the home?” How, exactly, a piece of furniture made in the style of the early 1800s related to New England settlers two centuries earlier is not clear. Nor was the discrepancy important.

Dave Doody

Molly McCrea’s means, as well as her devotion to fine old furnishings, are reflected in this scene in her colonial Carter’s Grove boudoir.

Individuals who couldn’t pull family heirlooms out of the attic had to content themselves with buying antiques or reproductions. “Everybody can’t have a grandfather, nor things that came over on the Mayflower, and those of us who have not drawn these prizes in life’s lottery must do the best we can under the circumstances,” wrote the author of an influential book, The House Beautiful, in 1878. Magazines like Godey’s Lady’s Book and House Beautiful and books like The Quest of the Colonial in 1906 were filled with advice for “people desiring to lay claim to a respectable ancestry,” telling them how to find antiques or reproductions, and how to decorate in the colonial fashion.

Colonial Revival was not authentic. It was not intended to be. Americans caught up in the Colonial Revival movement were not trying to “get it right.” Wealthy Archibald and Molly McCrea were not attempting to restore Carter’s Grove, ancestral home of one of the First Families of Virginia, to its original appearance. Their architect, the Colonial Revival specialist Duncan Lee, said Carter’s Grove was not meant to be a museum. It was meant to be comfortable. Now a Colonial Williamsburg exhibition building, the riverside mansion is shown as if the McCreas were still resident.

Many families less affluent than the McCreas bought up plain, old farmhouses and “improved” them into handsome homes. Books gave advice on how to turn the “smallest eyesore of a structure into a Colonial jewel.” Elaborate flower gardens helped paint a beautiful, if fanciful, picture of the past. Symbolism mattered more than reality. Colonial Revival houses had plain white interior walls, which evoked purity, rather than the wallpaper or colored paint the colonists favored. White exteriors with black or dark green shutters were preferred to Spanish brown. Symbols of industrious craftsmanship such as spinning wheels and candle molds decorated the living room. Furniture with simple lines signified virtue. “The design is as simple as a child, as pure as a lily,” reads an advertisement from 1900.

Some Victorian customs were too ingrained to be abandoned. Furniture was artfully arranged in conversation groups rather than against the walls, and Oriental rugs covered the floors. Upholstered furniture was generously stuffed. “Grandfather clocks”—the term was not invented until the 1840s—Windsor chairs, highboys, butter churns, and candlesticks galore were essential elements of the Colonial Revival decorating scheme.

Colonial architectural styles seemed fresh and new to Americans raised among the fuss of Victorian ornamentation. Elaborate styles like Renaissance Revival, Italianate, and Gothic Revival competed with, and then acceded to, the simpler forms of an earlier era. One advertisement for a house plan named “The Washington” says that:

when one looks thoughtfully at the Colonial style of architecture as shown in The Washington, his thoughts go back to the days when love of home and family were the most sacred emotions in the hearts of men. There are yet many with a steadfastness of purpose who inwardly long for the colonial days, and to such The Washington will be an inspiration.

Colonial architectural styles had been out of favor for years before they were revived in the late nineteenth century. Not everyone appreciated colonial structures. No less an architect than Jefferson said the colonial Georgian buildings at Williamsburg’s College of William and Mary were “rude misshapen piles, which, but that they have roofs, would be taken for brick kilns.” In the late 1890s a critic said plain eighteenth-century buildings were “outrageous deformities to the eye and taste.” “Happily,” she wrote, “they were all of such perishable materials, that they will not much longer remain to annoy travellers, in search of the picturesque.” But these were minority opinions. Americans had embarked upon a colonial roller-coaster ride in the 1870s and would not get off.

The Colonial Revival movement soared in the 1920s, fueled by the usual turmoil—a world war, the Bolshevik revolution, the Red Scare, and another spike in immigration, all of which increased the nostalgia for the good old colonial days. Enthusiasm plunged during the Great Depression, when only the wealthiest could afford to indulge in antiques, art, and architectural restoration. When the Great Depression ended with a second world war, interest in things colonial took a backseat to war patriotism and economic recovery. But by the 1950s, the Colonial Revival taste was climbing again. There were other styles in housing and furnishing, fads like Danish Modern that came and went, but Colonial Revival persisted.

Diane Dunkley, director of the Daughters of the American Revolution Museum and a Colonial Revival authority, says the 1970s show symptoms of another surge. The bicentennial renewed interest in the past, and Roots inspired an enthusiasm for genealogy. The preservation movement gained momentum. An antimodernism revived handcrafts like quilting, macramé, and furniture refinishing and launched the natural foods movement. People went “back to the land” or redecorated their homes in an old-fashioned “country” theme. The 1970s followed a period of social unrest not unlike the 1870s: the Vietnam War, urban riots, the assassinations, political scandal, and the sixties counterculture shook Americans. During these years, colonial styles ruled the furniture and homebuilding industries.

Dunkley says it is impossible to notice trends while they are happening,

but she wonders whether the early decades of the new millennium will bring

another surge of interest in the colonial style. The pattern is in place:

immigration problems, war, and economic dislocation. New neighborhoods

are being filled with McMansions built in the colonial genre, tourism

is booming at historic sites, genealogy has become the nation’s

fastest growing hobby, and a body of children’s literature, led

by the American Girls series, celebrates the American past.

One hundred years ago, an editor of House Beautiful magazine

wrote:

Every year sees the Colonial reaching more perfect expression, not only in furniture but in hangings, draperies, and all the accessories of decoration. . . . So we say that there will be no successor to the Colonial style. It is as near perfection in household furniture as can be created, and as such it needs no successor.

Of course, she was wrong. Art Deco and Italian Provincial attest to that. But in one sense, she may have been correct. The Colonial Revival is so firmly established throughout the United States that it has become the default style of architecture and home furnishings. It is not stagnant—each generation tweaks it a little, borrowing what it needs from the past to inspire the present—but it is constant, having “held its place in spite of the battering of other styles and other times,” as a magazine editor said in 1937. Synonymous with good taste, tradition, and American values, the Colonial Revival endures.

Mary Miley Theobald contributed to the spring journal “A Spell in Virginia: Noah Webster Visits the Old Dominion.”

Additional Resource:

See examples of architect William Lawrence Bottomley's designs at http://oncampus.richmond.edu/alumni/center.html.