“Easy, Erect, and Noble”

by Graham Hood

Hans Lorenz

With those words—“easy, erect and noble”—Thomas Jefferson described the George Washington he knew “intimately and thoroughly.” And this is the man we see in the full size of life in this great portrait, who stands easily, who meets and holds our eyes, not haughtily, as might be expected of a soldier who had taken the most powerful empire on earth down a notch, but with the sweet taste of victory on his lips and a carefully controlled satisfaction in his face.

“His person, you know, was fine, his stature exactly what one would wish.” Jefferson, a very different sort of man from Washington, wrote these words in the tranquility of retirement and might have written them with this picture in mind. He went on to say that his friend was “the best horseman of his age, the most graceful figure that could be seen on horseback.” We understand the depth of his esteem. Jefferson did not pay such compliments easily. We gaze at the portrait and we readily see, from the easiness of his pose, that Washington’s figure on the horse that nearby awaits him would be graceful indeed.

Here, painted at the height of the War for Independence, is the man on whom the whole cause seemed to depend, thought of sometimes as a weak soldier, sometimes as a slab of incommunicable granite, but increasingly as the war continued, as a man of extraordinary physical and moral strength. It is without doubt the first state portrait of the new America, and a most impressive image in its own right.

It would be natural to suppose that it was commissioned by a grateful United States Congress. After all, here was the man whose dedication and integrity had brought the American cause out of some very deep depths, who was to succeed Williamsburg’s Peyton Randolph as “The Father of Our Country,” and forever. When Congress summoned the commander in chief to report to it in Philadelphia, in late 1778, the future seemed brighter than it had for many arduous months. Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New England had been cleared of English forces and their hated mercenaries. France was now allied with America in the war against its archenemy.

If Washington had not prevailed in open battles, he at least had shown himself to be a master of retreat and adept at astonishing surprises that kept the enemy off balance. But Congress in these years seemed incapable of such largesse, and it is to the honor of the Supreme Executive Council, the governing body of Pennsylvania, that this great portrait was commissioned in January 1779.

The council, “deeply sensible how much the liberty, safety and happiness of America in general and Pennsylvania in particular is owing to His Excellency General Washington and the brave men under his command,” requested the general to sit for his portrait, which was to be placed in the council chamber so “that the contemplation of it may excite others to tread in the same glorious and disinterested steps which lead to public happiness and private honor.” The council also requested that the general sit to a member of its own legislature, portraitist Charles Willson Peale. As Washington had sat to Peale three times previously, the first as an affluent planter at Mount Vernon in 1772, he gave his immediate assent. His sittings were completed within ten days, and the portrait was finished in a month.

It was undoubtedly Washington’s choice that he be posed at the scene of his finest battles to date. In the lower-right foreground the captured German battle flags of Trenton are heaped. The British ensign is tossed on the ground to the left. Two cannons are shown in the foreground, representing two battles, while the distant view of Nassau Hall, in front of which soldiers in blue escort a column of red-coated prisoners, clearly indicates the battlefield of Princeton. Though Washington’s pose, as he leans on the convenient cannon barrel, seems casual, the American national ensign flying bravely in the upper right, the massed bayonets, and the expectant horse held by a ready aide all proclaim the power and capacity to strike again. For Washington, the details of military uniform were important. In Colonial Williamsburg’s version of this portrait—there are other copies—which is dated 1780, he is shown with the blue satin ribbon of the commander in chief across his chest and three stars on his epaulettes. The use of the blue ribbon to distinguish him from other senior officers dated from 1775. But, by personal order of the general dated June 18, 1780, silver stars on the epaulettes were meant to replace the ribbons—three stars for the commander in chief, two for a major general, one for a brigadier. Quite why Peale included ribbon and stars in this version is unknown, though there is no doubt that the ribbon enhances the pictorial qualities of the figure.

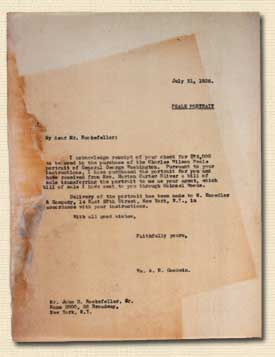

The Reverend W. A. R. Goodwin played middleman in Rockefeller’s purchase of the Peale.

- Colonial Williamsburg

It was necessary to get the details right. Peale copied the Hessian flags from the originals. He toured the battlefields, making sure that he had the topography correct, and he made studies of the cannons. Within three days of Washington’s last sitting a local newspaper, the Pennsylvania Packet, included a laudatory reference to the still-unfinished portrait. Expectations of a major new “resemblance” of the military hero ran high, and replicas at thirty guineas specie were already spoken of as being ordered.

It is impossible to believe that, after agreeing on the setting at Princeton and Trenton, the general and the painter did not discuss the focal point of this important commission—the pose of the central figure—and come to full agreement on it. Yet Washington was famously not a relaxed man, except that he appeared so on horseback. In this picture he is relaxed to the point of being languid, almost insolently so. Whatever Washington was, he was not insolent. Obviously he had to occupy front and center stage in the pictorial space, but quite so easily? No other portrait of him suggests this degree of relaxation.

There is a plausible explanation, which puts this state portrait in a wider context. The pose is virtually identical to that of a famous, full-length, life-size state portrait that the general knew well and that the painter had had ample opportunity to study—the coronation portrait of King George III, painted by Allen Ramsay less than twenty years before. A replica of this portrait, together with its pendent of the queen, arrived in Williamsburg in 1768 and was installed in the ballroom of the Governor’s Palace. Between that date and 1775, Washington was at the Palace many times, as his diary records. The portrait of the reigning monarch was something he could not possibly have missed or ignored.

Charles Willson Peale may have studied the new king’s portrait while he was training in London at the studio of expatriate Benjamin West from early 1767 to mid-1769. This was precisely the period when West was brought favorably to the attention of the king, who commissioned a large painting from him. It was the beginning of a long friendship between monarch and transplanted colonial. It is impossible to believe that Peale did not share in the rejoicing at West’s good fortune and great promise and, given his artistic curiosity in this period of his youth, difficult to believe that he was not somehow aware of the royal portrait, which was still quite new.

If Peale, on his return from England, did not also see a replica in the statehouse in Philadelphia, he certainly had opportunities to see the replica that Washington saw, at the Palace in Williamsburg. Peale visited the Virginia capital twice in the early ’70s, the second time, in 1774, to paint another full-length portrait—and it should be noted that such commissions were not common. This time it was to be of Peyton Randolph, speaker of the house and perhaps the most, certainly the second most, powerful man in the colony. But this time the occasion of the commission had nothing to do with royalty or military glory. Peale, a Mason, was to paint a portrait of Randolph as the newly appointed Provincial Grand Master of the Masonic Order. As the sitter was to be painted in “full Masonic costume” with regalia, it is easy to believe that Randolph walked the artist the short distance to the Palace, which he knew intimately, to look at another full-length figure adorned with much regalia, the portrait of George III.

The portrait of Randolph became one of the treasures of the Library of Congress, where the large mahogany book-presses that Peyton had inherited from his father, Sir John, also finished up. They had stood in the Randolph house on Market Square for fifty years before being sold to kinsman Jefferson, along with the books in them. Jefferson later sold them to the government to become the nucleus of the Library of Congress. The portrait of Peyton was destroyed in the fire of 1869.

Who first suggested this triumphantly ironic juxtaposition of provincial George—who had been denied a commission in the king’s army in the 1750s because he was provincial—with the most powerful George on earth? Painter, sitter, or witty, visually informed onlooker? Or no one? Perhaps it was nothing more than a coincidence. After all, life is often more ironic than art, and perhaps it just happened that way. But given the wide range of poses the general and the portraitist had to choose from, the prospect of such an amazing coincidence is too much for me to believe.

In any event, the portrait was rapturously received. Even before it was finished, the unofficial embassy of Spain in Philadelphia ordered five copies. The French ambassador bespoke one for his king, and the American envoy put in his request to take one to Holland with him. Despite this glittering success, Peale was disappointed that the state governments of Maryland and Virginia were conspicuously absent from the order books. Though there is some confusion about which replicas were actually bought and paid for, there are at least nine full-length versions in existence, one of which, destined to go to Holland with Henry Laurens, was captured by a British naval vessel commanded by the grandson of that governor of Virginia, the earl of Albemarle, who had authorized the twenty-two-year-old Washington to bear dispatches to the French on the frontier. The arrival of the portrait in England, together with evidence to prove that Holland was conspiring with the rebellious colonies, caused quite a stir.

Two of the more than 200 copies of the George III portrait painted by the Ramsay studio hang at Colonial Williamsburg—one in the Governor’s Palace and one in the DeWitt Wallace Decorative Arts Museum. A copy may have influenced Peale’s Washington.

-Hans Lorenz

One wonders if the king ever set eyes on that particular version, or perhaps on a mezzotint of it that Peale produced in numbers in mid-1780 for “two dollars, or the value thereof in current money.” If he did, it is doubtful that his comment was as shrewd and insightful as the one reported by Benjamin West. Conversing with West during the course of the war, the king asked the American-born painter what Washington would do if he prevailed over the English forces. West said that he thought Washington would return to his farm. In West’s words, the king responded, “If he does that, he will be the greatest man in the world.”

Colonial Williamsburg's version of the portrait came from the Carter family of Shirley, bought by John D. Rockefeller Jr. in 1928 for the not inconsiderable sum of $75,000. Wildly exaggerated values, of up to a quarter of a million dollars, supposedly from reliable sources, had been floating around for months before the deal was consummated. Rockefeller wanted to buy the house and land—this was the ideal plantation with which to supplement the historical messages of the colonial capital he was restoring. Though its owners were much reduced in circumstances, the plantation wasn’t for sale.

Asked how the family could even consider parting with this icon of the great man, which had apparently hung at Shirley for well over a hundred years, then-doyenne Marion Carter Oliver said offhandedly, “Well, he wasn’t a member of the family.”

What the Carters did do with the portrait, for well over a century, which proved to be of the greatest importance, was nothing. Nothing, that is, other than keep it out of the rain and away from too much light, fire, and sharp instruments. They preserved it from the well-meaning but often ruinous attentions of “restorers” of those times, with the result that we now judge it in superb condition and one of the truly great renditions of our national hero.

To me, this is the most stirring portrait of “The Father of Our Country,” though there is no doubt that Gilbert Stuart later did beautiful sketches and some lovely portraits of the older man. It is revealing to compare this Peale full length with Stuart’s full length—the famous and recently newsworthy “Lansdowne” portrait of 1796. The intervening sixteen years would seem to have borne very hard on the sitter. Though the pressures of the Revolutionary War had been arduous, the wearing effects of six years of the presidency would seem to have been much more. In the later portrait the head is not the head of a living man but of a monument. The figure seems reduced in its nobility, while the gesture is merely a formula, though the strong masculine hand is beautifully painted. This is truly the institution, not the man.

Stuart’s “Vaughan type” Washington portrait was considered an unsatisfactory likeness.

- Colonial Williamsburg

Even Stuart’s earlier head and shoulders portrait of the president—the “Vaughan” type—was criticized for its unsatisfactory likeness, but the best versions of that portrait are brimming with life compared with the Lansdowne full length. Peale was not the only critic, and he could hardly be called a disinterested one, but he detailed the distortions he saw in the Vaughan likeness from the person he knew—the complexion too florid, the character heavily exaggerated, and so on. The full length is even more so, on all counts. It is a long way, biographically and artistically, from the “easy, erect, and noble” young soldier to the national monument of Stuart’s portrait. Yet it is the latter that is more widely known today.

Visitors to Colonial Williamsburg’s DeWitt Wallace Museum may spend as long as they wish gazing at one of the museum’s, indeed the nation’s treasures, in its original frame and splendor, being inspired “to tread in the same glorious and disinterested steps which lead to public happiness and private honor.” They might also note, as Jon Prown, former Colonial Williamsburg curator and now president of the Chipstone Foundation, has pointed out, how symbolic it is, in more contemporary interpretive terms, that “Our Country’s” progenitor should be seen leaning so heavily on what he is leaning on. He also notes the particular and apposite way the painter shaped the sitter’s nether garment. Be that as it may, this portrait arouses many thoughts and feelings and spirits, and it could not be more fitting that such a fine version resides at Williamsburg.

Graham Hood, was Colonial Williamsburg’s vice president for collections and museums and Carlisle H. Humelsine Curator until his retirement in December 1997. His series “Attics Anonymous: On the Road for Colonial Williamsburg,” appeared in the spring and autumn 2001 journals.