How Much Is That in Today’s Money?

One of Colonial Williamsburg’s Most-Asked Questions Is among the Toughest

by Ed Crews

Dave Doody

William Sommerfield, who portrays George Washington at Mount Vernon.

Colonial Williamsburg visitors ask hundreds of questions every day on dozens of topics. Why did men wear wigs? What did farmers store in barrels? How long did it take to make a horseshoe? How far could a musket shoot? Where did Patrick Henry sit in the House of Burgesses? One of the most frequent inquiries is about money.

A visitor might learn from an interpreter that a Virginia teacher in 1759 earned a salary of £60 or that a pair of pistols sold for £3, 15 shillings, and 3 pence in 1755. Puzzled by the eighteenth-century prices, he asks: How much is that in today’s money?

How much is that in today’s money? It’s an obvious, simple, direct, and logical question. Yet, for all its simplicity and directness, economists say that “how much” is a devilishly complex riddle. In an article for American Heritage magazine, business writer John Steele Gordon has called it “one of the most intractable problems a historian faces.” Ronald W. Michener, an associate economics professor at the University of Virginia, sees the problem as more than intractable.

“Interpreters can’t answer this question,” he said in an interview. “The differences between today and then are too great to make a comparison. Viewed from the twenty-first century, life in colonial America was like living on a different planet.”

Answering the “how much” question may be impossible at worst or difficult at best. Nevertheless, economic historians are just as interested in “How much is that in today’s money?” as Colonial Williamsburg’s visitors and interpreters. Many historians want to know the modern equivalents of such things as the operating budget of a James River plantation in 1723, blockade runner profits in 1863, steel prices in 1886, wages of a Ford factory worker in 1935, or the cost of a B-17 in 1942.

The reason is simple. Such numbers would give them another insight, provide a common reference point between today and yesterday. It’s the same reason that visitors ask the “how much” question and interpreters keep searching for a satisfactory answer. According to John A. Caramia Jr., that search never ends.

“We always get to this question during staff training because interpreters know they will get this question. It certainly comes up frequently. They would love a magic number to give as an answer,” said Caramia, a Colonial Williamsburg program manager with an avid interest in the colonial economy.

Caramia knows firsthand that a magic number for “how much” would be handy. He appears as a costumed interpreter on Tuesdays at the Historic Area’s Geddy House for a thirty-minute presentation on running a family business in the 1700s. It touches on cash flow, credit, advertising, merchandising, and other topics.

But a magic number isn’t handy, and that’s just one of the challenges in interpreting colonial economic realities. The chief obstacle is time. Visitors and interpreters typically talk for a few minutes. That makes handling any complex issue tough, and economics covers some complicated ideas.

Dave Doody

John A. Caramia Jr., Colonial Williamsburg program manager, tosses a coin—which may be as good a way as any to determine the value of eighteenth-century money.

Another difficulty is currency. The eighteenth-century monetary

system makes no obvious sense in 2002. What are pounds, shillings,

and pence? Are they like dollars, dimes, and pennies? They aren’t.

In the 1700s, twelve pence equaled a shilling, and twenty shillings

a pound. The situation becomes more confusing when you learn that

before the Revolution each colony had a distinct currency, but

each adhered to the pound, shilling, and pence denominations.

Data is another stumbling block. Colonial economic information

doesn’t meet twenty-first-century standards of quality and

quantity. We live in an era rich in economic, business, financial,

and marketing data. Anybody can visit a library or the Internet

and find a wealth of statistical information. This material is

so vast, so personal, and so readily available that modern Americans

worry that others know too much about them. Privacy has become

a political and legal issue. When it comes to economic facts and

figures from the colonial period, the situation is different.

Tom Green

This mishmash of coins and paper currency could have been the day’s receipts at a single store in eighteenth-century America. Every colony had its currency, and money from England and other countries also circulated. Paper bills usually were valued lower than their coin equivalents.

Historian Thomas L. Purvis wrote about economic issues in the Almanac of American Life: Colonial America to 1763. There, he reported that more statistical data survives on the economy than any other aspect of colonial life. Unfortunately, it is incomplete “for any subject concerning the production, consumption and distribution of early American wealth.” Part of the reason is that neither British nor colonial officials compiled statistics that square with modern economic concepts like gross national product or per-capita earnings.

Such realities are of little solace to interpreters trying to answer “how much.” They suggest the safest response is: “Nobody knows precisely.” That is concise and truthful, but unsatisfying for visitors and interpreters alike. That answer derails further communication and the chance to spark more interest in eighteenth-century America. That frustrates everybody.

Another option comes from research conducted by John J. McCusker. He is the Ewing Halsell Distinguished Professor of American History and Professor of Economics at Trinity University in San Antonio, Texas. McCusker has written books on the colonial and British economies. His focus is the economy of the Atlantic world during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A fellow at the Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture in Williamsburg during the 1970s, he has taught economic history to costumed interpreters.

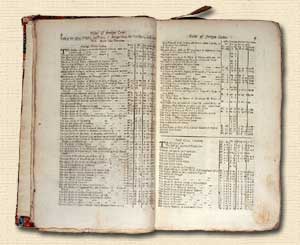

Courtesy of Robert Doares Jr.

This page from a 1753 “Gentleman’s Magazine,” giving the weights and values of denominations of coins foreign and domestic, gives an idea of the complexity of transactions and record keeping for colonial-era merchants.

For years, McCusker examined the puzzle of converting currency values across centuries. His work led to development of a method for converting late seventeenth-, eighteenth-, nineteenth-, and twentieth-century monetary sums into twenty-first-century equivalents. His system is explained in his book How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States. Released in 1991, the book came out in a second edition, reflecting refinements and further study, in late 2001.

Academicians debate all aspects of trying to convert money of the past into sums of the present. Typically, these discussions are technical and range from whether the exercise is worth the time and effort to calculation techniques and data. McCusker believes the debate is healthy and readily admits that his system offers approximations rather than hard and fast numbers, and relies on research done by him and others.

“The result, while far from perfect—and increasingly less perfect the further back in time we go—provides us with a reasonable approximation of the modern-day worth of a sum of money from some past time,” McCusker says of his work.

Dave Doody

Hard money—coins struck from precious metal—was the circulating medium of choice in colonial times. As interpreters Caramia and coachman Edward Merkley strike a deal on a horse, the groom, portrayed by Gregory James, gets a tip in change.

His approach relies on a commodity price index as the basis for computations. McCusker’s system requires his book and its tables and access to Internet calculators—www.eh.net/ehresources/howmuch/dollarq.php and www.eh.net/ehresources/howmuch/poundq.php—that crunch numbers. For example, using this system, you discover that £750 in Massachusetts during 1750 is worth roughly $48,000 in 2000.

Colonial Williamsburg’s interpreters couldn’t do these sorts of calculations while a visitor waited. But they could come to work with a few representative figures so that visitors would have an approximate answer to their question.

Or would they?

A visitor would know “how much” a price from the 1700s might be worth in 2000 dollars. By itself, though, such a figure means almost nothing. Caramia has considered this issue. He concluded that visitors, though they ask “how much,” want to know something else.

“I don’t think visitors are really asking about prices,” he said. “I believe they want to know: ‘What does it take for people to live comfortably in the eighteenth century?’ The question is about earnings and the cost of living. When it comes to interpretation, we have to make sure we understand the questions actually being asked. Our challenge is to give information our visitors really want.”

If Caramia is right, interpreters faced with “how much” might consider steering conversations with visitors toward colonial wages. Historians know some specifics about these. An interpreter can say that Jon Boucher, a schoolmaster in Caroline County, Virginia, earned an annual salary of £60 in 1759. McCusker’s system tells us that Boucher’s earnings would be roughly equal to $4,000 in 2000. But he also got his room and board, and was at liberty to take on other students. At that, Boucher probably wouldn’t buy a pair of pistols at £3 15s. 3d., about $340 in 2000; a saddle at £2, almost $180 in 2000; or a wig at £1 12s. 6d., about $145 in 2000. More likely purchases and their 2000 approximations include: a pound of butter, 4d., or $1.50; a yard of flannel cloth, 1s. 3d., or $5.60; a grubbing hoe, 5s. 6d., or $25; a prayer book, 3s., or $13.40; and a bushel of salt, 4s., or $18. All consumer goods above reflect 1755 prices in Virginia, and modern figures are rounded for ease of understanding.

Numbers like these give a glimpse of colonial life and begin to define what constituted luxury and necessity in early America. Visitors easily understand concrete numbers and their implications. Caramia said that this approach has limits, however. Again, data is the problem for wages and goods. Historians don’t have enough information about enough people to draw broad conclusions about workmen’s annual incomes. Surviving data is representative but not definitive.

“When you talk about wages and prices, you must begin by asking: ‘What did people make?’ Most people in the 1700s were self-employed, and there was no income tax,” Caramia said. So, no tax records on income were generated. “Today, we do pay income tax and, in the process, generate a lot of paperwork and data.”

A similar problem exists with prices.

What was the cost of living?

“In responding to this question, we do have a variety of retail prices to quote. But we need to remember that most items for sale had more than one price. These multiple prices reflected varying qualities of a particular item. It is also impossible to know how individual consumer decisions affected specific purchases,” Caramia wrote in a 1996 essay on prices and wages.

Although this approach has much to recommend it, the University of Virginia’s Michener says there are limits to any answer provided for “how much.”

“Price indices miss the point. There’s no dollar income today that would put you in a comparable position to 250 years ago,” said Michener, who has researched the colonial New England economy. “It was a different world. I’m skeptical about the analogy between specific dollars today and money then.”

The differences that Michener notes range widely, covering technology, attitudes, and the abundance of natural resources. If you were down and out in colonial New England, you could eat lobster, which was plentiful. The poor today cannot survive on lobster, he said. If you got a minor cut and it became infected, it could kill you. But, today, we have penicillin.

During the 1980s, historian James B. M. Schick undertook a creative exercise in colonial American history to try to bridge the economic gulf Michener believes divides the past and present. Schick’s experiment in “how much” highlights the dramatic differences.

For example, seventeenth-century immigrants were told to buy a foul-weather canvas suit at 7s. 6d. Schick figured the best modern approximation was an L. L. Bean Thinsulate Gore-Tex Maine Warden’s Parka and hood at $180. Outdoorsmen may agree that Schick made a good choice. There is, however, no comparison in the comfort and durability of canvas and modern hi-tech synthetic materials. Likewise, Schick discovered that the only regular ocean service in 1989 between England and America was the deluxe liner Queen Elizabeth II. He found a deeply discounted fare of $999. In 1624, the passage was £6. Clearly, though, the differences are immense between the luxurious and comfortable QE II and a cramped, dangerous seventeenth-century English merchantman.

Dave Doody

Interpreter Sandy Gibb makes a purchase from Caramia at his shop in the James Geddy House in Colonial Williamsburg. A merchant weighed his coins to reckon the value of their metal.

Despite the gulf, Virginia’s Michener believes you can discuss “how much” if you frame the answer as a discussion about standards of living. He suggested sharing with visitors a household budget from the 1700s. Modern Americans could readily connect with a budget, which could show what colonial families consumed, their expenses, the percentage of annual income spent on items and categories of items, and the relative material scarcity of their time.

McCusker said that providing more historical detail and context

could help. Under ideal circumstances, McCusker said, visitors

curious about “how much” would have time for a discussion

with interpreters that addressed eighteenth-century standards

of living. It might cover consumerism, lifestyles, and how a person’s

work determined what he could own and enjoy.

McCusker and Caramia understand, however, that visitor time is

precious. Interpreters already know a great deal. Circumstances

require them to share their knowledge in bits during thousands

of brief encounters.

“It’s tough to give an easy answer that captures the full flavor of the times,” Caramia said. “Maybe we have an opportunity here to help people understand the process we use when we want to learn about the past.”

Ed Crews contributed to the spring journal “You Really Can Fall in Love with the Sound of Harpsichord: Peter Redstone Builds a Barton,” a story about a replica of a portable eighteenth-century musical instrument.

Additional resources:

Online currency conversions

http://www.eh.net

What’s a Dollar Worth?

http://minneapolisfed.org/research/data/us/calc/

The Leslie Brock Center for the Study of Colonial Currency

http://etext.lib.virginia.edu/users/brock/

National Bureau of Economic Research

http://nber.org/cycles.html