Buchanan Town Improvement Society

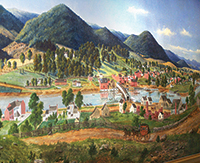

An 1855 painting by Edward Beyer of Buchanan, Johnston’s birthplace.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

The Everard House, built about 1718, one of Williamsburg’s oldest surviving buildings.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

The Coke-Garrett House, where Johnston’s friend Lottie Garrett lived.

Library of Congress

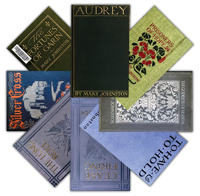

Home schooled in rural Virginia, Johnston was a best-selling novelist by thirty-two. To Have and to Hold sold 500,000 copies.

Internet Archive

A productive writer, Johnston wrote eight books between 1913 and 1921, set anywhere from Columbus’s time to the Civil War.

Special Collections, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

Cora Smith and her sister likely retailed stories of old Williamsburg to Johnston and put her up at their home during a 1901 visit.

The Mind of Miss Mary Johnston

by Ivor Noel Hume

She stares out at us from her posed, formal photograph with a small mouth and eyes that seem to disbelieve what she is seeing. It is a face some might construe as the façade of a simple mind and an empty head. But they would be wrong—dead wrong.

In 1902, Mary Johnston was an accomplished author whose imagination would put tumbledown Williamsburg on the national map and keep it there, to be born again a quarter of a century later in the hands of John D. Rockefeller Jr. Two of its eighteenth-century historic houses became part of Johnston’s legacy, albeit overshadowed by the great names that fathered the United States.

At the turn of the twentieth century, the two-story dwelling now known as the Coke-Garrett House was home to Lottie and Mary Garrett, sisters of its owner, Van F. Garrett, professor of chemistry at the College of William and Mary. June 25, 1902, in a letter to Lottie Garrett, Johnston recalled her “memory of the day and night which Corlie (cousin Eloise?) and I spent in your charming home.” It was, however, the second house whose association with Johnston lingered into the 1950s. Known today as the Everard House, in 1907 college President Lyon G. Tyler described it in his book Williamsburg: The Old Colonial Capital as “Audrey’s House.” It was, he said, “a small, typical house of the eighteenth century, on the east side of the Palace Green, made famous by Mary Johnston as the house of Audry described in a novel of that name.” “Audrey” was the correct spelling of the novel’s name, the story-and-a-half house is believed to have been built about 1718 for gunsmith John Brush, and it is one of the earliest surviving domestic structures in the city.

Mary Johnston was born November 21, 1870, in Buchanan, a Botetourt County, Virginia, village, the oldest of six children. Her father, lawyer John William Johnston, had served the Confederacy as an artillery officer, but in the post–Civil War years, business and civic commitments took him away from the Allegheny Mountains, leaving Mary and her siblings to be raised by their mother. She died in 1889, when Mary was nineteen. The girl had always been pale and sickly, and so had no schooling away from the house—which makes her later achievements more interesting. By the time she was thirty-two, she was among the nation’s best-selling novelists.

There were no reporters around to ask how she spent her childhood, what she learned of her father’s war service, or what books she read. All these, and more unanswered questions, would have relevance as Johnston’s literary career blossomed. Her first book, Prisoner of Hope, written while she was still tending her family in Botetourt County, was published in 1898 and focused on colonial Virginia. Its success prompted another colonial tale, To Have and to Hold. At first serialized by the Atlantic Monthly in 1899, the book was published by Houghton Mifflin in 1900 and sold more than 500,000 copies.

Perhaps buoyed by her book royalties, Johnston moved from the mountains to Richmond’s 113 East Grace Street. She was there in April 1903, when she wrote letters to Lottie Garrett, the first saying that she “was sending another photograph,” presumably of herself, and the second no more than a hello note. The letters preserved in the Garrett Family Papers, 1786–1928, at the College of William and Mary’s Earl Gregg Swem Library, began in March 1901, after Lottie Garrett nominated Johnston for membership in the Colonial Capital Branch of the Association for the Preservation of Virginia Antiquities. The association had its first meeting at Williamsburg’s Tayloe House in 1889. By the turn of the century, its roots were deep in the soil of architectural preservation and the protection of the South’s traditions of patriotism, courage, and decency. Most of the original members were lifelong residents of Williamsburg, Norfolk, and Richmond. Lacking local connections, Mary Johnston almost certainly rested her qualifications on her fame as a writer of inspiring colonial novels.

Written in 1901, Audrey was published in 1902, and so had not made its mark when, from Virginia Beach on March 19, Johnston wrote her first known letter to “My dear Miss Garrett.” In it, she said she was planning a Williamsburg visit. A month later, she wrote from Birmingham, Alabama, thanking the Garretts for their hospitality but giving no clue to the purpose or length of her Williamsburg stay. Whether the book was formulated during the visit is not known, but it is clear that by the time she wrote it she had amassed enough background history to plant it authentically amid the Virginia gentry of 1727.

Were it not for evidence to the contrary, one could reasonably deduce that Johnston drew her local history from sessions with Lottie Garrett in her home across the lane from the site of the colonial Capitol—which the APVA had acquired in 1897. Instead, as President Tyler said, the source was the smaller house on Palace Green, then probably known as the Smith home. Cora and Estelle Smith were another pair of unmarried sisters who reportedly provided a roof over Johnston’s head while she wrote her Tidewater novel. There is no hint in Lottie Garrett’s letters that there was such a stay or association.

Nevertheless, a sufficient friendship had developed for Lottie Garrett to attempt a visit to Johnston in Richmond that prompted a sorry-to-have-missed-you response May 9, 1903. Then silence until April 1907, when she wrote from the Hotel Seville in New York regretting that she could not accept Garrett’s invitation to return to Williamsburg, but saying, “Did you know that I really love Williamsburg and did you ever guess that I am just a little fond of you and your sister Mary.” That might be read as a wealthy author saying something nice to an ordinary Williamsburg person. That Garrett kept these short letters might today be seen as evidence of a fan-to-star fixation.

The last of Johnston’s letters was written from Richmond in December 1907 and may have been a response to another invitation. Addressed to “My dear Miss Lottie,” it said, “Some day I am coming to Williamsburg again to see the dear old place and certain dear people.” That Mary was but fifty miles away in Richmond suggests that “some day” was not just around the corner.

Perhaps borne along by the success of To Have and to Hold, Audrey became the nation’s fifth best-seller of 1902. It is likely that in the Petersburg rectory of the young Reverend Dr. W. A. R. Goodwin, father of restored Williamsburg, there was a copy of Johnston’s new book. If he read it, his imagination could not but be stirred by her description of Duke of Gloucester Street:

Broad, unpaved, deep in dust, shaded upon its ragged edges by mulberries and poplars, it ran without shadow from the gates of William and Mary to the wide sweep before the Capitol. Houses bordered it, flush with the street or setback in fragrant gardens; other and narrower ways opened from it; half way down its length wide greens, where the buttercups were thick in the grass, stretched north and south.

Johnston had created in her mind a Williamsburg as serene and beautiful as it would become in the hands of its 1930s restorers. But hers was the town as she imagined it in 1727. As she sat in a window of the Everard House, she could look across Palace Green to the red brick of the George Wythe House, which would later become the heart of Goodwin’s domain. Her hero, she wrote, “lodged upon Palace Street in a square brick house, lived in by an ancient couple who could remember Puritan rule in Virginia, who had served Sir William Berkeley, and had witnessed the burning of Jamestown by Bacon.” Johnston’s old couple was fictional. She knew that, but she did not know that its square brick home would not be built until 1752.

Visible information available to Johnston as she re-created life in early Williamsburg was minimal. The Governor’s Palace burned in 1781, the Capitol in 1747, the Wren Building of the college in 1859 and 1862, and about 1770 the old theater next door was demolished. The detailed appearance of the three key colonial buildings went unrecorded until 1937, when the Bodleian Plate of 1740 was discovered in Oxford’s Bodleian Library. Of the surviving frame buildings in 1900, all Johnston could expect to learn was that some were old. They doubtless looked it.

In the mortifying years following the Civil War, there had been little incentive and few dollars to spend on gardens or sidings. And such new buildings that were going up or converting old to new focused on the needs of now and showed little or no respect for way back when. This was the town that Goodwin saw when he took over the rectorship of Bruton Parish in 1903. Like Mary Johnston, he was inspired by the traces of all he could no longer see, but unlike her, he felt ghosts urging him to make them live again. It would take him the rest of his life and millions of Rockefeller dollars to make that happen. Johnston could bring the past alive with only a pen and a ream of paper.

Goodwin’s ghosts were seen only by him. If Thomas Jefferson’s shoe buckles were not of the right shape, they alone knew it. Johnston’s people, however, were in danger of becoming unreal as soon as she added an undocumented detail. Her hero entered a store and found at the back of it “a row of dusty bottles, and breaking the neck of one with a report like that of a pistol, set the Madeira to his lips.” What could be wrong with that, asks anyone who lacks knowledge of 1727 glass bottles? The answer was that bottles of that period had such thick necks that to break them one had to smash the shoulder and lose the wine. In 1902 Virginia, nobody knew one old bottle from another, and Mary Johnston would be dead before they did. In fairness, however, one might mention that today many a movie company does not know how antique its bottle must be to be period correct.

Mary’s colonial world was one not of dust and broken bottles, but of the serenity of nature. She wrote:

Away from the shadow of the trees, the full moon had changed the night-time into a wonderful silver, silver day. Narrow above and below, the stream widened before him into a fairy basin, rimmed with reeds unruffled, crystal clear, stiller than a dream. The trees that grew upon the farther side were faint gray clouds in the moonlight, and the gold of the fireflies was very pale. From over the water, out of the heart of the moonlight wood, came the song of a mockingbird, a tumultuous ecstasy, possessing the air and making elfin the night.

Looking again at her portrait, it is hard to imagine the tumultuous ecstasy that burned behind the mask of Johnston’s staring eyes. It is equally hard to believe that her ears could hear the roar of cannon and the cries of dying men at Chancellorsville, but her Civil War novel of 1911, The Long Roll, was regarded as the best of its genre before Margaret Mitchell’s Gone with the Wind, published in 1936—the year that Johnston died. Johnston’s book should not be confused with another of the name published in 1911. It is the diary of Charles Johnson, who served in the Hawkins Zouaves from 1861 to 1863.

Johnston also wrote what she knew. Her father had seen war’s horrors, proud Confederate families remembered the Battle of Williamsburg and the ignominy of Federal occupation, and the scorched ruins of Richmond were still there for her to see. Johnston carried the carnage through to its end in her second Civil War book and titled it Cease Firing. Again, her work was praised, and her publishers and readers waited for more. Between 1913 and 1921, she wrote eight books, leading in the following year to 1492, her account of the Columbus voyages.

As in all her books, the main characters were the products of Johnston’s mind, and whether male or female they presented her views of life as she knew it in the early twentieth century.

An activist for women’s rights, she used her literary fame as the podium for her voice. In 1909 she founded the Equal Suffrage League of Virginia, and promoted her cause before the legislatures in Tennessee and West Virginia. She was opinionated and forceful, one might say driven, and her espousal of Women’s Suffrage led to waning royalty checks as some of her early readers fell away, preferring adventures to lectures. Undeterred, she kept writing, her mind more nimble than her always-fragile health, and in 1911 she left Richmond and returned to the kinder climate of the Alleghenies. At Warm Springs, where Jefferson had enjoyed the waters, she and her unmarried sisters built a still-existing mansion they called Three Hills.

A victim of Bright’s disease, Johnston died there at the age of sixty-five. Brought back to Richmond, she lies in Hollywood Cemetery alongside the military, political, and literary great of the Old Dominion. Few remember, however, that she made Williamsburg the household word that it remains.

Everard House visitors learn about its colonial owners: John Brush, who died in 1727, the year Johnston’s Audrey came to town; William Dering, who taught dancing in the 1740s; and lawyer and sometime Williamsburg mayor Thomas Everard, who died in the house in 1781. No one recalls, however, that the fictional Pocahontas-like Audrey, star of Charles Stagg’s next-door theater, also died there, having been stabbed by a spurned suitor. “They bore her into the small white house and up the stairs to her own room, and laid her upon the bed,” Johnston wrote. “There was a crowd in Palace Street before the theatre. . . . A man mounting the doorstep so that he might be heard of all, said clearly, ‘She may live until dawn,—no longer.’” Nor did she.

Though drawn from the author’s imagination, the ghosts of Colonel William Byrd and his daughter Evelyn may yet be at the bedside of Mary Johnston’s dying heroine as she lay in that upstairs room of the Audrey House.

Author and archaeologist Ivor Noël Hume contributed to the autumn 2012 journal a story on the history of the concept of Britannia. He is indebted to Harriet Seraydarian for genealogical assistance, and to historian Wilford Kale for transcriptions of the Garrett letters.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Mary Johnston, To Have and to Hold (Boston and New York, 1900), https://archive.org/details/tohavetoholdjohn

- ———, Prisoners of Hope: A Tale of Colonial Virginia (Boston and New York, 1900), https://archive.org/details/prisonersofhopet00johniala

- ———, Audrey (Boston and New York, 1902), https://archive.org/details/audrey00unkngoog

- ———, Cease Firing (Boston and New York, 1912), https://archive.org/details/cu31924022013829

- Lyon Gardiner Tyler, Williamsburg: The Old Colonial Capital (Richmond, 1907), https://archive.org/details/williamsburgold00tylegoog