Online Extras

Ice Cream: The Process, Tools & Ingredients

Ice cream, molded to look like a fruit basket, takes pride of place on the dessert table set at the Governor’s Palace.

In the Palace kitchen, Brantley blends cream and sugar and egg yolks, with a touch of strawberry preserves for added flavor.

Depending on the ambient air temperature, it can take from thirty minutes to an hour and forty-five minutes of hand spinning for the two quarts of the mixture to freeze and solidify.

Some Cold, Hard Historical Facts about Good Old Ice Cream

by Mary Miley Theobald

There are more myths about the origins of ice cream than flavors at Baskin-Robbins. Debunking them is among the jobs of the Historic Trades cooks at Colonial Williamsburg’s Governor’s Palace kitchens. They concoct eighteenth-century versions of the frozen treat in front of guests every month.

Some sources say the ancient Romans invented ice cream, others that Marco Polo brought the discovery back to Italy from China. All agree that Catherine de Medici introduced the French to ice cream when she married the future King Henri II. Not to be outdone by Europeans, some Americans have said ice cream was first made by Martha Washington, or brought to this country from France by Thomas Jefferson, or invented by First Lady Dolley Madison at the White House. By dint of repetition, these entertaining tall tales go unchallenged—at least until they reach the Governor’s Palace kitchen.

“There is no documentation for any of these claims,” says journeyman Robert Brantley. He has spent hours researching the topic. “These stories were created during the nineteenth century by ice cream sellers who were looking for a marketing angle.”

Each story contains a kernel of truth. The Romans did mix snow or chipped ice with various flavorings, but that makes Slurpees, not ice cream. Most historians agree that Marco Polo visited China in the thirteenth century and that the Chinese were probably the first to invent an iced dairy product, but if the Venetian traveler ever saw or tasted such a memorable food, he makes no mention of it in his writings. And Catherine de Medici of Florence, Italy, did marry the future king of France in 1533, but that was before Italian cooks had learned to artificially freeze liquids and more than a century and a half before the earliest known French ice cream recipe.

“When visitors see us making ice cream at the Palace,” Brantley says, “many say, ‘They wouldn’t have had ice cream back then!’ And that’s our opening to explain about the history of ice cream in colonial America and to debunk some of the common myths.”

Ice cream probably originated in China, but little reliable research has been done on the subject. As early as the seventh century, a Chinese frozen milk product is described. Another description, this one poetic, of frozen milk survives from the twelfth century. If those two bits of evidence leave historians skeptical, there is a more reliable mention of ice cream being served at the Mogul court in the fourteenth century.

Knowledge of ice cream could have spread overland along the Silk Road routes from China through the Middle East and into Italy, but it seems more likely that what spread west was the knowledge of how to freeze things by the combination of ice and salt. The “endothermic effect” of this mixture draws heat from the adjacent liquid, allowing people to freeze fluids and, incidentally, to make ice cream.

Humankind learned to make fire hundreds of thousands of years before it learned to make ice. Anthropologists at Israel’s Hebrew University say prehistoric humans discovered how to use fire about 790,000 years ago. Historic humans discovered how to use the cold a few hundred years ago, perhaps shortly before the thirteenth century, when the endothermic effect was mentioned in an Arab medical book. That book refers to an earlier book, now lost. The process fascinated men of science—particularly physicians. An Italian doctor wrote of it in 1530, a Spanish doctor in 1550. English statesman and scientist Sir Francis Bacon wrote about it decades later. With this knowledge, cooks could use ice and salt to freeze liquids. With ice alone, they had only been able to make them cold.

They still needed ice. While any peasant living in a cold climate could collect ice from ponds in winter, only the rich and royal could afford the luxury of year-round ice. The wealthy built icehouses, where great chunks of frozen water cut from rivers or lakes were stored underground between layers of straw, sawdust, or other insulating media. A well-designed icehouse could preserve ice through the summer. The ice—coming as it did from rivers or lakes—was not clean, and the sawdust must have made it gritty, but people did not put ice in their drinks. They cooled them from the outside, by putting their drinks in ice.

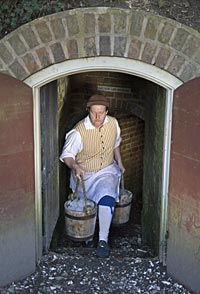

There was an icehouse in eighteenth-century Williamsburg—in the gardens behind the Governor’s Palace. Shirley Plantation on the James River in Charles City County had one, as did Rosewell, the York River Page family home in Gloucester County destroyed by fire a century ago. George Washington built an icehouse at Mount Vernon; so did Thomas Jefferson at Monticello. But collecting and keeping a year-round supply of ice was a luxury beyond the means of most Americans.

Making flavored ice is simple; making flavored frozen milk or cream is not. In addition to the difficulty of procuring ice, sugar was expensive in colonial times.

Ice cream’s European debut probably was in Italy, probably in Naples, probably in the latter part of the seventeenth century. It spread through the royal houses of Europe. Early English mentions include a 1671 feast of King Charles II in which “one plate of Ice Cream” was served, and a 1688 banquet to celebrate the birth of the son of James II.

English cookery books begin to include recipes for ice cream in the eighteenth century, starting with the 1718 edition of Mrs Mary Eales Receipts. Mrs. Eales was the royal confectioner to Queen Anne. These early recipes called for cream and fruit but no eggs. By the middle of the century, recipes said the mixture should be stirred during freezing, and the ingredients included eggs. That resulted in a smoother, richer, creamier substance that closely resembled modern ice cream.

Recipes advised ice cream makers to use one container for the cream mixture and a second, larger one for the ice and salt. Mrs. Elizabeth Raffald’s cookbook of 1775 says to set the mixture

in a tub of ice broken small, and a large quantity of salt put amongst it, when you see your cream grow thick round the edges of your tin, stir it, and set it in again till it grows quite thick, when your cream is all froze up, take it out of your tin, and put it into the mould you intend it to be turned out of, then put on the lid, and have ready another tub with ice and salt in as before, put your mould in the middle, and lay your ice under and over it, let it stand four or five hours.

The French invented a simple pot freezer to accomplish this. They called it a sarbotiere, and Denis Diderot included a drawing of it in his encyclopedia. Owning a sarbotiere was convenient for one’s servants, who were doing the work, but not necessary. An English cookbook author, Hannah Glasse, recommended buying “two pewter basons,” the smaller with a tight cover, from a pewterer—a device that would work just as well as a sarbotiere. Pewter was the preferred material because it was strong. Mrs. Mary Randolph’s 1824 cook book, The Virginia Housewife, says, “The freezer must be kept constantly in motion during the process, and ought to be made of pewter, which is less liable than tin to be worn in holes, and spoil the cream by admitting the salt water.”

Ice cream began to appear in the American colonies during the first half of the eighteenth century. The first known instance of ice cream being served occurred in Maryland in 1744, when Governor Thomas Bladen put it on his dessert table. It was May, and the sight of something frozen to eat in the warm months astonished the guests. One of them, William Black of Virginia, wrote of it in a letter, which survives. Black mentions “a Dessert no less curious: Among the Rarities of which it was Compos’d, was some fine Ice Cream which, with the Strawberries and Milk, eat most Deliciously.”

Historians know of at least two royal governors who served ice cream at the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg. A hailstorm in July of 1758 gave Governor Francis Fauquier the chance to make ice cream in the summer. Hailstones so large they broke every window on the north side of the Palace fell to the ground, and when they were collected—doubtlessly not by the governor himself—“he cooled his wine, and froze cream, with some of them the next day.” It was Fauquier’s first year in Williamsburg and his first exposure to the violence of American weather. Ten years later, his successor, Lord Botetourt, arrived in Williamsburg, where he served as governor until his death in 1770. The inventory of Botetourt’s belongings included pewter ice molds, which would have been used to form ice cream into pretty shapes. The inventory mentions “1 tin ventilator,” a device that could have doubled as a sarbotiere, or his servants could have used the double pewter basin method.

There was probably no icehouse behind the palace in 1758, or Governor Fauquier would not have sent servants out to gather the hailstones. There was an icehouse by Botetourt’s tenure; historians know that he made repairs to it. It is likely that Fauquier had the icehouse built. Precisely when remains a mystery.

So a few Americans were eating ice cream long before Jefferson went to France in 1784 as American ambassador to the court of Louis XVI. Although Jefferson did not introduce ice cream to America, he encountered it in Paris, and he enjoyed it enough to jot down a recipe that calls for “2. bottles of good cream. 6. yolks of eggs. 1/2 lb. sugar” to be flavored with vanilla and frozen in a sarbottiere. Jefferson took notes on icehouse construction when traveling in Italy and Virginia before building his at Monticello near the north terrace in 1802. It required “62 waggon loads of ice” from the Rivanna River to fill. A 1796 inventory lists “2 freising molds” in the kitchen, so his servants were making ice cream at least that early. When he was president, Jefferson had an icehouse built for the President’s House—what we today call the White House—and on Independence Day in 1806, hired a servant to turn the ice cream maker. This introduced many to ice cream, hence the belief that Jefferson brought the dish to America.

Martha Washington did not invent ice cream any more than Jefferson or Dolley Madison, but she served it at Mount Vernon. The Washingtons acquired a “cream machine for ice” in 1784, the year George directed his estate manager to build an icehouse on his estate.

And the favorite flavors of the day? Strawberry, vanilla, and raspberry seem to have been popular. A recipe for apricot ice cream appears in one cookbook with the notation that the cook can use “any sort of fruit if you have not apricots.”

Rob Brantley has also found documentation for coffee, tea, pistachio, Parmesan, and chocolate flavors. He says that eighteenth-century chocolate could be cayenne spicy, making colonial chocolate ice cream taste quite different from today’s. Perhaps the strangest flavor is found in Mary Randolph’s cookbook—oyster ice cream. “Essentially it was frozen oyster chowder,” Brantley says. “They served it unsweetened, with the oysters strained out. Imagine the astonishment of the guests who were served something like that in the summer.” Not a favorite at Ben & Jerry’s, but worth a try on a hot summer day.