Online Extras

Livestock Slideshow

Livestock as an Object Lesson: History Education on the Hoof

by Ed Crews

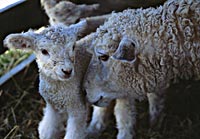

Out with the old, in with the ewe–and her lamb: one of Colonial Williamsburg’s Leicester Longwool sheep tends to her young.

Coach and Livestock’s Karen Smith, Elaine Shirley, and Richard Nicoll, holding hoof, feather, and wheel, in the Colonial Williamsburg stables.

Try to imagine an eighteenth-century American town without horses and carriages in the streets, pigs and chickens in the pens, and cattle and sheep in the pastures. Tough to do. In the 1700s, animals were as much a part of the urban landscape as homes and shops, courthouses and taverns . . . well, you get the idea. Livestock and wooden-wheeled conveyances were as much parts of a community as people and their houses. You couldn’t create a workable picture of the place if the frame didn’t include some from all of them.

The animals and coaches in The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation’s Historic Area give guests a sense of how the town appeared and how people lived when the city was capital of colonial Virginia. They support the foundation’s educational mission.

“We need the livestock to create life on the scene,” said Richard Nicoll, the Bill and Jean Lane Director of Coach and Livestock, “and to make Williamsburg a living museum.”

Elaine Shirley, supervisor of rare breeds, said, “The animals do add life to the area. Today, we live in a world where the only animals people see often are cats and dogs. It wasn’t that way during the 1700s.”

Williamsburg then would have been a busy and noisy place with oxen and mares moving along the streets, hens and roosters clucking and crowing in private yards, and cows and calves being driven to market. Colonial Williamsburg hasn’t enough creatures to recreate that environment, but the animals the foundation does have are attention-getting crowd pleasers.

“Animals are one of the biggest attractions, especially for children. They like to get up close and watch the sheep or talk to the people who care for them or go on a carriage ride with the horses,” said Karen Smith, supervisor of barn operations. “We don’t have a roller coaster, but, for lots of children, the carriages are the next best thing.”

Every day, the eighteen-member staff of the foundation’s stable and livestock operation cares for nearly a hundred animals—feeding them, moving them, checking on them, and calling a veterinarian when necessary. It keeps the coaches and wagons rolling through the Historic Area, and, apart from the daily demands, when events require, it accommodates such special jobs as working with still photographers, preparing a carriage for VIPs, and participating in the videotaping of classroom programming for the foundation’s electronic field trips.

“It’s always a moving target here,” Nicoll said. “Things are always getting rearranged. Our job is to keep it all moving and keep it all running. That means maintaining the equipment in good shape, operating safely, and watching out for the health of the animals.”

Nicoll took charge of the department in 1984. He grew up in the country near Somerset, England. As a young man, he worked on farms, loved dealing with animals, and attended the Royal Agricultural College. He developed an interest in carriages along the way. That led to jobs with people who owned and drove them. It also gave him experience and knowledge about a subject foreign to most people in the twenty-first century.

During the past quarter century, the stable and livestock department has evolved into three sections. Probably, the best-known people are the coach drivers. Thousands see them annually as they wheel through the Historic Area. They support special events and visits by such people as Queen Elizabeth II, and have become one of the symbols of Colonial Williamsburg, their number expanding to meet the demand for their services.

“We’ve got more vehicles on the streets than ever before,” Smith said. “They’re the best we’ve ever had. Our operations have really grown.”

Less visible than the drivers, but no less important, is the stable staff, and the people caring for the foundation’s rare breeds, preserving farm stock that could become extinct without human intervention.

One of the biggest challenges of keeping vehicles rolling and tending so many animals is finding employees qualified for tasks increasingly outside the vocational mainstream. Many people have experience with horses, but carriage driving, if not a lost art, is perhaps arcane. Moreover, the dwindling number of American farms has shrunk the pool of people with animal husbandry skills.

“We hear from lots of animal lovers, but often they can’t milk a cow or don’t know when an animal is sick,” Shirley said. Successful applicants find more in the work than a paycheck.

“It’s really rewarding,” Smith said. “It’s rewarding working with animals but it’s also rewarding educating people about livestock. People often come to Williamsburg with no experience with animals. Some know nothing about where eggs or milk come from. They’ve never petted a horse and don’t know how. After they spend time with us, they start to get used to the idea that animals have other roles than just being pets.”

For Shirley, not only are the educational aspects of the rare breeds satisfying; so is knowledge of the role that Colonial Williamsburg plays in keeping alive a small portion of America’s rich agriculture heritage. Every time an infant is born in the rare breeds program, the odds increase that these breeds will survive and thrive.

Nicoll said he’s certain the stable and livestock department’s educational mission will remain as central as the appeal of the carriages and animals.

Ed Crews, a Richmond-based writer, contributed to the spring 2009 journal an article on Ossabaw Island pigs. This is the final installment in a series on Colonial Williamsburg’s coach and livestock operations.