Deism

One Nation Under A Clockwork God?

by James Breig

Photography by Dave Doody

From left, Todd Norris as minister of Hickory Neck Church in Toano, Virginia, with Phil Shultz, Sharon Hollands, and Bill Barker as Thomas Jefferson at communion.

From left, Carolyn Wilson, Robert Weathers, Ron Carnegie as George Washington, Donna Wolf, Jack Flintom, Megan Brown, Jeffrey Villines, Janine Harris, and Kaitlin Kovach.

In old age, James Madison, here in a copy of Gilbert Stuart’s painting, defended belief in God as a moral necessity to man.

A deist but not an atheist, Thomas Paine maintained, “I believe in God,” but aimed his pen at the Christian religion.

Joseph Wright’s 1782 portrait of Benjamin Franklin, who anticipated discovering the truth about Jesus after his death.

On Christmas Day in 1769, Charles Pyne, a bookseller in England, perhaps with an eye to enlarging his stock without increasing his overhead, swiped several books from one Thomas Roberts. Pyne grabbed a three-volume set of works by Jonathan Swift, filched a history book, and walked off with two volumes titled Deism Reveal’d. Arrested, he pleaded guilty and was transported out of England, perhaps to America. About four years later, Philip Fithian began tutoring the children of Robert Carter—a wealthy and powerful man who lived on a Virginia plantation and owned a large home next door to the Governor’s Palace in Williamsburg. When Fithian catalogued Carter’s library, he listed a treatise on government by Sir Francis Bacon, the Anglican Book of Common Prayer, and The Canterbury Tales. He also noted that resting on a shelf between books about William Congreve and William Shakespeare was a two-volume work: Deism Reveal’d.

Whether in the hands of a thief who knew what would sell or in the library of an influential Virginian, the volumes testify that people of the eighteenth century addressed the ideas of what was sometimes denominated “theological rationalism,” a reason-based faith. Broadly speaking, the idea is that a first cause is responsible for the universe and that the universe runs, like a clockwork, on its own. Some would adopt deism’s precepts; others would reject them.

Benjamin Franklin, in his Autobiography, wrote that “some books against Deism fell into my hands; . . . The arguments of the Deists . . . appeared to me much stronger than the refutation; in short, I soon became a thorough Deist.”

Sir John Randolph, one of the leading legal lights of Williamsburg and the only Virginia-born colonial to be knighted, made sure that his 1735 will clearly described his religious beliefs: “I have been reproached by many people . . . and drawn upon me names very familiar to blind zealots such as deist heretic and schismatic.”

Feeling impelled “to vindicate my memory from all harsh and unbrotherly censure of this kind,” he professed his sincere belief that “Jesus was the Messiah who came into the world in a miraculous manner. . . . I am also persuaded . . . that the dead shall rise at God’s appointed time.” By detailing his adherence to orthodox Christian doctrines, Randolph rebutted accusations that he was interested in deism, a sect—if it merits a term implying an organized system of tenets—that rejected the incarnation, the resurrection, and the trinity.

Franklin confessed to some doubts about Jesus’ divinity, and Thomas Jefferson razored his way through the Gospels, keeping words that seemed to him to be authentically Jesus’, but cutting what he took to be the corruptions of other New Testament contributors.

As a cultural movement, deism was strongest from, roughly, the mid-seventeenth century to the mid-nineteenth—but it is with us yet.

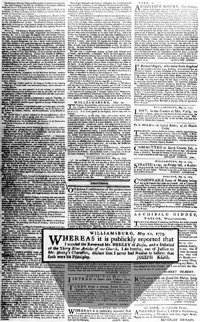

Still debated more than 200 years after the Constitution was written is the question of whether the United States was ordained by Bible-believing Christians or Bible-doubting deists, who held that God was a disinterested being with a hands-off view of the universe he created. Such debate, which can raise hackles and voices in our times, engendered fierce emotions in the 1700s, as Randolph’s will, and a May 20, 1773, issue of the Virginia Gazette, published in Williamsburg, testify. The Gazette carried an advertisement placed by Joseph Kidd that said in part, “Whereas it is publickly reported that I accused the Reverend Mr. Henley of Deism . . . I do hereby, out of Justice to Mr. Henley’s Character, declare that I never had reason to believe that such were his Principles.”

That being called a deist was cause for such a newspaper notice suggests how contentious the concept was. Contentious, yes; complicated, no. Deism was defined with sixteen words in Samuel Johnson’s 1755 dictionary: “The opinion of those that only acknowledge one God, without the reception of any revealed religion.” To some, the term was a synonym for atheist. A sermonist said in 1670: “We have a generation among us . . . called Deists, which is nothing else but a new court word for Atheist.” But the word deism derives from deus, the Latin word for god, and its practitioners accepted a supreme cause responsible for all that exists.

Deism’s invention is often credited to Edward, the first Lord Herbert of Cherbury, England, who died in 1648. In The Faiths of the Founding Fathers, David L. Holmes, a professor of religious studies at the College of William and Mary in Williamsburg, catalogues Herbert’s “classic five points of Deism”:

- That God exists

- That “he ought to be worshiped”

- That practicing virtue is the primary way so to do

- That sins can be repented of

- That there is life after death

On the fifth point, Jefferson said that the deceased “ascend in essence to an ecstatic meeting with the friends we have loved and lost and whom we shall still love and never lose again.” John Adams captured much of Herbert’s five points in one sentence: “My religion is founded on the love of God and my neighbor; on the hope of pardon for my offenses; upon contrition; . . . in the duty of doing . . . all the good I can, to the creation of which I am but an infinitesimal part.”

Because deism was never a formal sect and had no hierarchy to fix its principles, each adherent could bend it to individual liking, often moving it along traditional Christianity continuum as one manipulates a pointer along a slide rule. On one end of the scale, Washington could be ranked as a deist who attended church services, was a vestryman, quoted the Bible, commended religion, and prayed. At the other end stood Thomas Paine, who recorded his disdain for Christianity in The Age of Reason. In his view, God never communicated with men, Christianity was a fable, and miracles were fictions. Nonetheless, he said he was not an atheist. In a letter to Samuel Adams, Paine wrote that he penned The Age of Reason to keep the French from “running headlong into Atheism” during their revolution, and to ensure that they would hew to “the first article . . . of every man’s Creed who has any creed at all—‘I believe in God.’”

Paine’s use of the word “God” was atypical of deists. The preferred terms ran to Almighty Being, Supreme Author, Providence, Superior Agent, the Supremely Perfect—a Franklin phrase—and the Great Governor of the World, used in the Articles of Confederation.

The vocabulary hints at why deism flourished during the Enlightenment, when reason and science were exalted. During the eighteenth century, men catalogued animals and plants, charted the stars and planets, founded museums to preserve the past, and composed dictionaries and encyclopedias to systematize knowledge. When that impulse turned to religion, it leaned toward a scheme that accepted what was rational and cast off what could not be scientifically proved—walking on water, for example, or the notion of a triune deity.

That approach infuriated many Christians. In a 1755 article in The Gentleman’s Magazine, an English journal, a writer fulminated against what he saw as “all revealed Religion, turned into Ridicule, by Men who set up for Sense and Reason.” In 1753, a reader of the Virginia Gazette pleaded with the editor to print articles “to shew that the Scriptures are the Word of God,” because he had “Reason to fear Deism has some Adherents in Virginia.” Writing in 1799 of her husband’s death, Patrick Henry’s widow said:

He met death with firmness, and in full confidence that through the merrits of a Bleeding Savour his sins would be pardoned. . . . I wish the grate Jefferson & all the heroes of the Deistical party could have seen my . . . husband pay his last debt to nature.

Such back-and-forths—“Mr. Paine versus Mrs. Henry”—could be a shorthand way of describing it, providing concise but simplistic ways of imagining the tension between deism and Christianity in the eighteenth century. Deists tended to be all over the place in beliefs and opaque in their expression. Like most human beings, they shifted and honed their opinions. A one-liner uttered when someone is young does not necessarily capture that person’s attitude in middle age or retirement. A deist could go to church in the morning, rail against organized religion in the afternoon, and pen a speech in the evening praising the salutary effects of faith. Considered to have been a deist, James Madison, late in life, wrote, “Belief in a God All Powerful wise and good is so essential to the moral order of the World and to the happiness of man, that arguments which enforce it cannot be drawn from too many sources.”

Colonial Williamsburg historian Linda Rowe said, “Franklin, Washington, and Jefferson all attended church services frequently to the end of their lives. They gave money to church building funds of several denominations, and attended Baptist, Presbyterian, Episcopalian, and Unitarian houses of worship. Most made no secret of their conviction that regular religious practice was necessary to public virtue upon which the survival of the republic depended.”

Franklin, whose life almost spanned the eighteenth century, mutated from defining himself as a deist to saying that deism had “perverted” his friends. In his forties, Franklin commended “the excellency of the Christian religion above all others ancient and modern.” As a senior citizen at the Constitutional Convention in Philadelphia, he suggested in vain that the participants pray for God’s guidance. “The longer I live,” he said, “the more convincing proofs I see of this truth, that God governs the affairs of men.” The same Jefferson who clipped the miracles from the New Testament also said, “I am a Christian, in the only sense in which” Jesus “wanted anyone to be: sincerely attached to his doctrines, in preference to all others; ascribing to himself every human excellence; and believing he never claimed any other.”

As some eighteenth-century Americans moved the pointer on the slide rule of belief, what pulled them toward deism might have been its “allowing belief in God without assigning divine responsibility for natural disaster and horrendous human behavior,” wrote Jon Butler, a professor of American history at Yale University and author of Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People. In addition, he said, being a deist avoided “the vicious strife produced by denominational discord and religious war that had disfigured the ‘Christian’ world for centuries.” Rowe said that “the appeal of moderate deism for Franklin, Washington, Adams, Jefferson, and others was that it allowed for belief in a God who deserved to be worshipped by human beings but was not dependent upon biblical revelation, prophecy, and miracles as matters of faith. I say ‘moderate deism’ because none of these men completely abandoned the religious lessons upon which they were raised. They could be very critical of organized religion and theological twists and turns precisely because, in their view, these man-made institutions had corrupted the simple message of Jesus and obscured the best way to follow his teachings.” Gary Scott Smith, author of Faith and the Presidency: From George Washington to George W. Bush, said deism’s appeal lay in how well it comported with . . .

Enlightenment-influenced belief in the importance of reason as the principal mode of discovering and discerning truth. Moreover, such people preferred Deism’s contention that God was a watchmaker who did not interfere with the operation of the universe he wound up as well as its rejection of the deity of Christ, miracles and the authority of the Bible. Finally, those who accepted Deism relished its focus on Christ’s moral teaching rather than on theological speculation, personal conversion and religious experience, which orthodox Christianity emphasized.

Alf J. Mapp Jr., author of Faiths of Our Fathers: What America’s Founders Really Believed, sees deism’s lure “in its presentation of a world whose organization and material manifestations were expressions of pure reason.”

To some modern historians, “deism” is too simple a term to describe the complexity of the belief system of some Americans in the 1700s. The Reverend Thomas Buckley, SJ, professor of American religious history at the Jesuit School of Theology at Berkeley, said that belief is more complex than saying a person shrugged off Christianity and put on deism: “Too many historians keep calling the ‘founding fathers’ Deists. Even Thomas Jefferson on his worst days was not one of their ranks.” A better term than deist for most of them, Buckley said, is “rationalistic Christian.” Agreement on that point comes from Dreisbach, who said he thinks “there were relatively few Deists in America. There were a few elites who gravitated to a form of theistic rationalism, but we’re talking about a relatively few, albeit influential, elites.”

Toward the end of his life, one of those elites, Franklin, composed what was, in effect, his religious creed. As a quondam deist, man of science, and Enlightenment figure with an open mind, he believed in what could be proved. So he wrote: “As to Jesus of Nazareth . . . I have . . . some doubts as to his divinity. . . . I expect soon an opportunity of knowing the truth.”

James Breig,, is an Albany-based writer and editor who contributed to the winter journal an article on the eighteenth-century’s East India Company.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Brooke Allen, Moral Minority Our Skeptical Founding Fathers (Chicago, 2006).

- Jon Butler, Awash in a Sea of Faith: Christianizing the American People (Cambridge, MA, 1990).

- David L. Holmes, The Faiths of the Founding Fathers (New York, 2006).

- Alf J. Mapp Jr., Faiths of Our Fathers: What America’s Founders Really Believed (Lanham, MD, 2003).

- John Meacham, American Gospel: God, the Founding Fathers, and the Making of a Nation (New York, 2006).

- John T. Noonan Jr., The Lustre of Our Country: The American Experience of Religious Freedom (Berkeley, CA, 1998).

- Michael Novak and Jana Novak, Washington’s God (New York, 2006).

- Thomas Paine, The Age of Reason

- Gary Scott Smith, Faith and the Presidency: From George Washington to George W. Bush (Oxford, 2006).