The Emergence of Popular Culture in Colonial America

by Christopher Geist

Photos by Dave Doody

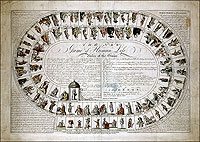

In the Game of Human Life, at least in this penny-cheap broadside version, a pair of dice and a pinch of luck offered amusement and, at the end, immortality for its players.

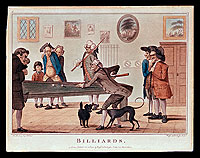

Abroad, horse and foot races were sports of choice for improving a person's leisure hours. Indoors, a game of cards or billiards, seen here in an eighteenth-century English print by Henry Bunbury, prompted friendly competition at the local tavern.

Alongside homemade ones, commercially produced toys became more common in the eighteenth century, offering recreation and, betimes, social or moral instruction to children. Maya Canaday, left, plays with Eleanor McCoy at the Benjamin Powell House.

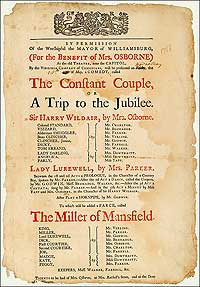

Playtime in Williamsburg began when a theater opened in 1716. The Constant Couple headlined in the 1768 season.

Pick-up sticks for big boys. Colonial Williamsburg interpreters Brian Simpers, left and Bill Rose at play, wielding ash clubs to brain each other in a bout of cudgeling. Behind them, Willie Wright, Joe Garcia, Frank Megargee and Jeff Geyer.

Colonial Williamsburg's John Turner re-creates the tune and dance masters who brought music to taverns and towns.

The sport of kings skewed less royal in the colonies, though still well-heeled and -shod owner, jockey, and horse. At public gatherings such as court and muster days, races were featured events. Phil Shultz, left, and Emmanuel Dabney play the ponies.

In his landmark study of popular culture in the American colonies, Benjamin Franklin shed light on the tastes and pastimes of prominent Virginians. Although Thomas Jefferson greatly favored fiddle tunes, a good portion of the music stored on his MP3 consisted of harpsichord pieces. George Washington enjoyed reality TV shows, and he was most proud of his wife's foray into publishing. Martha Washington's Living had become a solid success throughout the colonies. And few were surprised when Patrick Henry let it be known that his favorite film genre was the political thriller.

Of course, that's fantasy and absurd. There was no popular culture in colonial times. Or was there? Popular culture is that level of culture that is easily understood, shared by most, but not necessarily all, members of society, and is widely accessible. For most of us, popular culture is something with which we fill our leisure hours. Many products of popular culture are consumer goods that we eagerly purchase to demonstrate our participation in and understanding of current tastes and fashions. The mass media play an important role in disseminating the popular arts and entertainments that help to shape our popular culture.

Popular culture requires a population sufficiently large to support widespread distribution of consumer goods, one with enough leisure and income to participate in and enjoy the common culture. Certainly, these conditions were present in North America by the onset of the Revolution. By mid-century the colonial population was exploding, growing at nearly twice the rate of Europe's, doubling about every twenty-five years. In 1720, there were 474,388 European and African inhabitants of what would become the United States. By 1750, there were 1,207,000, and by 1775 more than 2,500,000.

More important than the growth of the population were the increasing size of the middle class and the gradual increase in leisure and income, which created demand for consumer goods. And, to a degree, even the lower levels of society could participate in the growing consumer revolution. Historian Lorena Walsh writes that by 1750 "Tidewater Chesapeake households at all levels of wealth were both able and willing to buy a wide range of non-essential consumer goods either previously unavailable or long considered unimportant."

To the extent that individual consumers and families could afford them, demand grew for such goods as novels and other books for light diversion, cards and card tables, sheet music, children's books and toys, equipment for such outdoor sports as hunting and fishing, and decorative prints such as those produced by William Hogarth.

Simple board games, such as The Royall and Most Pleasant Game of the Goose—basically a broadside printed with a circular track over which players raced through hazards, guided by throws of the dice—offered inexpensive parlor entertainment. Cribbage boards became popular, and parlor card games such as loo and whist filled many a leisure moment. The lower classes seemed to enjoy playing at put, an early version of poker. Playing at dice was popular as well, especially games such as Hazzard, which required no special game table and was an affordable diversion. Many card and dice games, of course, were vehicles for gambling and attracted moral reproach and condemnation from some segments of colonial society.

Backgammon boards and billiard tables were popular among the wealthy by the 1770s, and the lower sorts, at least the men, could indulge in such recreations at the ubiquitous public taverns and coffeehouses. Writing of his New England in 1761, John Adams said, "In most country towns you will find almost every other house with a sign of entertainment before it." As early as 1722, a Charlestown, Massachusetts, tavern owner advertised tables for all who "had a Mind to Recreate themselves with a Game of Billiards." Then, as now, popular recreations attracted critics. One writer singled out what he considered the distasteful and vile practice of New York's tavern life: "I mean that of playing backgammon (a noise I detest) which is going forward in the public coffee-houses from morning till night, frequently ten or a dozen tables at a time."

Although many children's toys were still homemade and more closely tied to folk than to popular culture, by the 1770s there was a respectable variety available for purchase from colonial merchants. Advertisements in Williamsburg's Virginia Gazette offered tops, marbles, dressed babies, dolls with glass eyes, toy fiddles, toy watches, puzzles—often instructional in that they related English history or moral lessons when completed—balls, and toy soldiers. Bilbo catchers, still available in restored Williamsburg, are made of a cup connected by a string to a ball. Players toss the ball into the air and try to catch it in the cup as it comes down.

By the time of the Revolution, historian Jane Carson writes, second to their dolls, the "favorite toy of little girls" was the tea set, sold in Williamsburg shops. This toy offered the colonial girl an opportunity to play at the enormously popular adult pastime, the tea ceremony, which had captivated Americans from the wealthiest to the lower classes. So popular had tea services and daily rituals surrounding the consumption of the beverage become that a survey of estate inventories in New York from 1742 through 1768 shows that wealthy and lowly estates in cities as well as in rural areas included the essentials: teapots, cups, saucers, and teaspoons. The boycott of tea called in response to the Townshend Act of 1767 did not alter the behavior of many colonials, and even those who gave up tea continued their tea ceremonies by substituting chocolate or coffee.

American printing presses, augmented by shipments of English materials, provided popular literature at increasingly affordable prices. Simple broadsides, single sheets of paper printed on one side and sold for a penny, had been in circulation since the late 1600s. Most carried simple poems written in a basic and limited vocabulary recounting events great and modest, ranging from domestic tragedies and didactic moral lessons to natural disasters and battles. Often these poems were set to music and gained an additional popular audience as they were performed in taverns, on the streets, and in homes. By the 1680s, colonists had access to chapbooks, cheap books with paper covers. Some provided stories of shipwrecks; others recounted the last days and executions of celebrated villains and pirates. Still others were lurid, such as one available in 1685 Boston: The London Jilt, or the Potlick Whore, which promised the reader "Several Pleasant Stories of the Misses' Ingenious Performances." Even a modern reader might be taken aback by such a claim.

More Americans became, as Colonial Williamsburg historian Kevin Kelly has written, "literate, if not literary," by the middle of the eighteenth century. Public libraries appeared throughout the colonies, and fiction, mostly by English novelists, became popular. Many works popular among the colonists are known today. Henry Fielding's Tom Jones, Samuel Richardson's Pamela, and Laurence Sterne's Tristram Shandy are three examples of works enjoyed in their original English versions as well as in pirated American imprints. Religious tracts, histories, and political writings were also popular in the colonies.

No published work illustrates the emerging power of colonial popular culture more than does Thomas Paine's tract in support of American independence, Common Sense. Published January 10, 1776, it went through edition after edition and sold more than 100,000 copies by the end of March. According to historian James Hart, "Not since its time has any book had such a quick or widespread sale relative to the population." One copy was sold for every twenty-five residents of the thirteen colonies.

Newspapers offered local news and advertising, but they provided a more significant contribution to building a common, or popular, colonial culture. Much of their content consisted of reprints of articles and essays from other newspapers throughout the colonies as well as from England. They also offered poetry, humor, and satire. Early versions of what would become the American magazine also appeared and, although not truly successful until the 1800s, hinted at things to come.

Almanacs appeared in the colonies in 1639 and were established as among the most widespread and popular genres of American literature by the time Ben Franklin's Poor Richard appeared in 1733. These little compilations of meteorological and astrological information also included poetry, proverbs, essays on history and science, bits of wit and wisdom, features on agriculture, and short biographies of historical personalities. They were more or less indispensable in many a colonial household.

Not to be overlooked is the manifestation of eighteenth-century popular culture known as the theater. Williamsburg's first permanent theater opened in 1716, and by the 1730s, New York and Charleston had theirs. Early in the eighteenth century, itinerant performers appeared regularly throughout the colonies outside New England, where public "stage-plays, interludes, and other theatrical entertainments" were opposed on grounds that they "discourage industry and frugality . . . increase immorality, impiety, and a contempt for religion." By the time of the Revolution, however, opposition to theatrical presentations on moral grounds had almost disappeared, even in New England. Some modern historians argue that most opposition to the theater in the colonies was based on economic rather than strongly held moral or religious objections. Traveling companies arrived in a community, presented perhaps a week's worth of plays, and moved on, taking a bit of the ready currency of the town with them.

Even the rather lowly could afford admission to the rowdy and uncomfortable accommodations of the pit, while the well-to-do occupied more expensive box seats. One imagines that the quality of the performances varied from the brilliant to the awful. The variety and number of plays performed were impressive. The 1773–74 season in Charleston offered fifty-eight plays, from Shakespeare to light opera. Low comedies, farces, and romances were popular, as were plays with moral and political overtones, such as Joseph Addison's Cato. The titles of some of the plays performed in Williamsburg indicate the variety of their subjects and reflect colonial tastes: False Delicacy, School for Libertines, The Musical Lady, The Constant Couple, The Orphan, The Babes in the Wood are suggestive.

John Gay's The Beggar's Opera of 1728, one of the most enduring plays of the eighteenth century, was being performed in Williamsburg as late as 1770. Gay's musical contributed to another of colonial America's popular pastimes, the enjoyment of music.

Several of Gay's tunes were perennial hits, including "My Love Is All Madness and Folly" and "I like a Fox Shall Grieve." Words and tunes such as these were disseminated via broadsides or collected in inexpensive songbooks. Common tunes, often from the 1600s, were put to new words again and again. An example is the drinking song "Anacreon in Heaven," which was used with at least twenty-six sets of lyrics before Francis Scott Key set his "Star Spangled Banner" to it in 1814. And many a traditional folk ballad found its way onto broadside sheets during the era. Music was available everywhere and was performed in taverns and coffeehouses, at street fairs, on the stage, and in homes.

Itinerant dance masters with small pocket fiddles, such as the one played by modern balladeer John Turner in Colonial Williamsburg's taverns, traveled the countryside teaching the latest steps in homes and rented spaces in colonial towns. Dancing schools were found in the larger urban areas, where they offered lessons by subscription. Though popular throughout the middle and southern colonies, dancing was most trendy in Virginia and South Carolina. From balls in the Governor's Palace to small, rural gatherings, Virginians loved to step all manner of dances from formal minuets to reels, country dances, and rough and tumble jigs.

Militia musters, court days, and public executions became community festivals. Such occasions included games, foot races, wrestling contests, horse races, and cudgeling, in which contestants used a stout ash stick to bludgeon an opponent into submission. Colonials also enjoyed itinerant magicians, acrobats, trapeze artists, jugglers, and the presentation of exotic animals. A lion was exhibited as early as 1716, and a camel traveled the colonies in 1721. By 1730, trained monkeys were on the circuit. Bearbaiting, long popular in England, and cockfighting were common, if indelicate, spectacles.

Although far from the overwhelming mass-mediated sensual assault we associate with modern popular culture, on the eve of the Revolution an emerging common culture had taken shape throughout the thirteen colonies that would become the United States. And that popular culture would explode in the years after the Revolution. By the 1820s, it was established and poised to rush toward the modern mediated culture we know today.

But did the colonials realize what was happening? Some did. It seems significant that, as the Revolution approached, the Continental Congress deemed it necessary to call for a limit on popular amusements and entertainments to preserve energy and resources for the struggle. Congress urged the colonies to "discourage every Species of Extravagance and Dissipation, especially all Horse Racing, and all Kinds of Gaming, Cock Fighting, Exhibitions of Shows, Plays, and other expensive Diversions and Entertainments." Popular culture had become a force to reckon with.

Christopher Geist, professor emeritus at Ohio's Bowling Green State University, contributed a story to the autumn 2006 journal about popular opinion during the Revolution and Vietnam.

Suggestions for further reading;

Cary Carson, ed., Of Consuming Interests: The Style of Life in the Eighteenth Century (Charlottesville, VA, 1994).

Jane Carson, Colonial Virginians at Play (Williamsburg, 1989).

Foster Rhea Dulles, A History of Recreation: America Learns to Play (New York, 1965).

James D. Hart, The Popular Book: A History of America's Literary Taste (Berkeley, 1963).