Anniversaries and the Origin of History

A Jamestown 400th Anniversary Story

by Michael Olmert

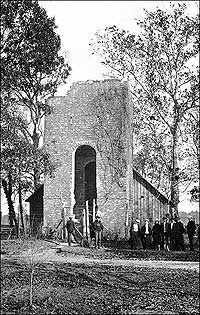

The remains of the brick church at Jamestown figure prominently in anniversary commemorations of the colony's 1607 founding.

The custom of commemorating significant and abiding dates, like 1607, has long been with us. It is what calendars were invented for, it seems.

The Bicentennial. Benjamin Franklin's 300th birthday. Your 20th wedding anniversary. The 200th year since Lewis and Clark set out. 225 years since Washington beat Cornwallis. The passage of 400 years since the Jamestown English landed. All cause for commemoration. Why?

The Jamestown colonists must have seen this moment coming. Some of them at least. They would have expected, four hundred years on, that generations unknown to them would honor the memory of their part in 1607.

For some of them, it was a lark, a job, an adventure, an unlooked-for Act Two in life. For the people waiting for them on shore, it was an invasion. For nearly all, Native or English, it turned out to be a personal disaster, a bitter end, not a new start. Still, from our comfy perspective we remember and honor them for starting something that seems important to us, something still under way.

The inclination to memorialize meaningful dates—something we regard as modern—was ingrained in Western culture by 1607. It is likely some at Jamestown were acquainted with the most famous case of instant anniversary making, which had occurred a decade earlier in Shakespeare's Henry V. The scene is just before the battle of Agincourt, October 25, 1415, which happens to be the feast of Saints Crispin and Crispinian. As King Henry is rallying his troops, who face long odds in this away game against the French, he says:

This story shall the good man teach his son;

And Crispin Crispian shall ne'er go by,

From this day to the ending of the world,

But we in it shall be remember'd;

We few, we happy few, we band of brothers;

For he to-day that sheds his blood with me

Shall be my brother; be he ne'er so vile,

This day shall gentle his condition:

And gentlemen in England now a-bed

Shall think themselves accursed they were not here,

And hold their manhoods cheap whiles any speaks

That fought with us upon Saint Crispin's day.

Crispin and Crispinian, whose saints' day was also the Battle of Agincourt, were promised eternal remembrance by Shakespeare. Image courtesy of Wilanow Palace.

Marking the days of solstice, Stonehenge in England was likely an agricultural calendar and perhaps a religious shrine. Image courtesy of Pete Strasser.

In the event, the English win the battle, but the Hundred Years' War drags its slow self along until 1453. Still, this dramatic immortalizing of October 25 was a rousing success, as every student of Shakespeare knows:

He that outlives this day, and comes safe home,

Will stand a tip-toe when the day is named,

And rouse him at the name of Crispian.

He that shall live this day, and see old age,

Will yearly on the vigil feast his neighbours,

And say "To-morrow is Saint Crispian:"

Then will he strip his sleeve and show his scars.

And say "These wounds I had on Crispin's day."

Old men forget: yet all shall be forgot,

But he'll remember with advantages

What feats he did that day.

The other great anniversary maker of the period was the poet John Donne. His "The Anniversary" plays upon the idea of a one-year-old memory of the day he first saw his beloved. The rest of the world has undergone natural decay during the year, Donne suggests, but not their love. It is still fresh and robust. The poet's goal is to keep tending this love until it achieves the status of legend:

Let us love nobly, and live, and add again

Years and years, till we attain

To write threescore; this is the second of our reign.

The little joke in the last half-line is a small dose of reality. It's fifty-eight years and counting until their reign, as world-class lovers, reaches three score. Still, the point for us is plain: at least two prominent English poets alive in 1607 were also alive to the idea of institutionalizing memory via anniversaries—an idea perhaps as old as history.

The most powerful engine of institutionalizing memory was Christianity. For instance, in Henry V, Agincourt is expected to get a double dose of memory down through time because the battle occurs October 25, the feast day of Crispin and Crispinian, the patron saints of shoemakers and leatherworkers. They were Romans martyred in France in ad 287. For Shakespeare, there was an English connection because some of their relics were said to have been enshrined at Faversham village church in Kent.

Kings and princes rise and fall on the Wheel of Fortune in front of blindfolded Lady Fortune in a 1503 French painting. Image courtesy of Bibliotheque Nationale.

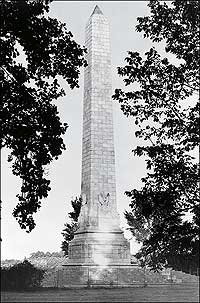

Anniversaries and public memory and are built of stone and mortar in the Jamestown monument, raised for the tercentenary in 1907

In effect, the liturgical year, that panoply of saints' days and feast days, saw to the orderly unfolding of belief, from Advent and the events surrounding the miraculous birth, through Lent, Passiontide, and Easter, and on to the astounding revelations in the Pentecostal run-up to Advent again. After which, the same saga happened over and over, identically, every year.

The ecclesiastical calendar would have been deeply ingrained in the minds of all Jamestowners, pious or not, because they looked to it for their holidays as well as their holy days. Its cyclical regularity was comforting in an unpredictable world; to say nothing of the dependable way it delivered harvest ales and Christmas boxes to the lower classes each season.

Moreover, in the liturgical calendar, every saint's day was an anniversary, considered the day he or she died and so entered eternal life. So, it was never happy birthday, but happy death day. Such anniversary feast days encapsulated the whole point of Christianity, which in its best sense held out the hope of defeating death in just this way.

Such anniversaries have a moral dimension beyond that of reflecting on the goodness of a saint's life. They remind the faithful that ours, too, is an only life, and that we must gather our rosebuds while we may. Ecclesiastical anniversaries are naturally backward looking and force people to reflect on their personal past. For most of us, this can be painful, the arctic realization that we have wasted precious years, "the time torn off unused." It is what the classical world saw as a carpe diem moment. That is, "seize the day" before it is too late. It is the moral response to time ticking away.

The cyclical pagan year deeply influenced the Christian view of history that, within a fundamentally linear conception, it is also circular: what goes around comes around, and those on high, such as kings, often end up very low. That last theme was even given a name in literature and folklore: the Wheel of Fortune. And if people wanted confirmation of its existence, they need only consult the histories of Charles I in Britain, Louis XVI in France, and most of the royalty in the plays of Shakespeare.

The Jamestown colonists would have been aware of the wheel of fortune by way of centuries of popular culture, not to mention English literature. There is no more persistent theme in the books and poems and broadsides some of them would have read or listened to on the way out from England. The wheel offered hope: Because even as it took down the mighty, the wheel was equally capable of elevating the lowly. Many at Jamestown were counting on that.

In this matter of anniversaries, we've seen endlessly repeating seasons, ecclesiastical calendars, eternally cyclical time, and the wheel of fortune, all concepts that are circular and come round again and again. The same themes are embedded in the word "anniversary," whose first syllable is the Latin root for both "year" and "ring." And since rings have neither beginnings nor ends, they are considered everlasting; hence, the wedding ring.

"Anniversary" was first used in English about 1230 in a devotional book for nuns. It brings together the Latin annus for year, plus versus for turning, yielding "returning yearly." In time, English developed phrases for the anniversary of a death, including "year-day" and "mind-day," fourteenth-century words that bow in the direction of mindfulness for the soul of the departed. The phrase "wedding anniversary" is not found in English until 1673.

Everyone's essential anniversary, the birthday, was widely celebrated in the classical world; the word enters the English tongue via the Old English gebyrth-daeye about the year 1000, though the custom was practiced centuries before, in Roman Britain.

Birthdays are celebrated in the Bible. In Genesis, Pharaoh's birthday is the day that Joseph's interpretation of dreams bears fruit. King Herod's birthday is mentioned in the Gospel of St. Matthew. In Shakespeare's Julius Caesar, Cassius's birthday coincides with the date of the Battle of Philippi, in October 42 bc. Says Cassius, who is about to die: "This is my birth-day ...this very day was Cassius born." Then he makes an observation on the cyclical nature of all anniversaries, not just birthdays:

This day I breathed first: time is come round,

And where I did begin, there shall I end;

My life is run his compass.

A sense of time, and time passing, was all that was required for ancient people to start compiling anniversaries. Hard evidence for this is the creation of calendars. The Babylonians, Jews, Egyptians, Greeks, Hindus, Chinese, Zoroastrians, Mayans, and other societies had early calendars. Prehistoric people with no written language seem to have had a respect for time and calendars.

Consider a megalithic monument like Stonehenge, more than 5,000 years old, which can be shown to be an accurate device for calculating the winter and summer solstices, roughly December 22 and June 22. Only on the summer solstice, for instance, does the sun rise above a certain stone and its rays pierce into the center of the monument. The anniversaries of solstices and equinoxes are critical for sorting out an annual calendar, which was essentially a tool for knowing when to sow seeds.

A calendar that got out of whack would have meant disaster for agricultural people. Sow too early and the young sprouts freeze; too late, and the crops may not bear fruit before the snows fly again. The likely result: famine or extinction. These were the anniversaries it was fatal to miss.

To be sure, the solar and lunar calendar at Stonehenge was mainly a commemoration for practical, agricultural reasons, though it may well have had patriotic or religious or historical overtones. Still, it set the stage for memorial dates associated with sacred rites, with national heroes, and with august or harrowing deeds.

The custom of remembering great events in chunks of time larger than a year may have started with the close of the first millennium in ad 1000, which some Christians looked at balefully, expecting the Second Coming and a sound thumping from the Lord. The same concern was faintly heard at the end of the second millennium in 2000. In any case, the word "millennium" is postclassical Latin and is first found in a British text dating from about 1210.

It is mainly in the last two centuries that events in the deep past have been the subject of great public displays and celebration. But the word "centennial" is only used for the first time well after the Jamestown settlement. In 1788, the first grand "centennial" in England was the hundred-year anniversary of the Glorious Revolution, which brought William and Mary to the throne in 1688. Very early on, the form for such festivity becomes fixed. It involves music, speeches, flags, and fireworks.

The word "sesquicentennial," a 150-year celebration, is a largely American usage and began appearing in the second half of the nineteenth century, when there were sesquicentennials for the founding of Baltimore, in 1880, and Princeton University, in 1896.

When the 200th anniversary of Handel's birth was celebrated in London in 1885, it was called his "second centennial"; the word "bicentennial" was not used. In 1807, 3,500 people came to Jamestown for its 200th anniversary, called a Virginiad or the Grand National Jubilee; it is not known whether the term "bicentennial" was used. According to the Oxford English Dictionary,"bicentennial" appears to be first used in a published letter of 1901 to refer to the 1701 foundation of Yale University.

Two other Jamestown festivals were conducted in the nineteenth century. The first, in 1822, strangely ballyhooed the 215th anniversary of the founding of Virginia. Why 215 years? You can only suppose that the 200th anniversary went so well people could not wait for the 250th to turn up. Again, they called it a Virginiad. Finally, in 1857, the 250th anniversary was celebrated. The day featured 8,000 revelers, sixteen steamships, and a two-and-a-half hour speech by John Tyler, the former president.

A tri- or tercentennial, a 300-year celebration, is used for the first time in 1817, in connection with the 300-year anniversary of Martin Luther and the Protestant Reformation in 1517. In 1907, Jamestown celebrated its tercentennial with a grand exposition in Norfolk, at which Teddy Roosevelt, Booker T. Washington, and Mark Twain made addresses. Twain came twice, both times by yacht from New York, and seems to have enjoyed himself, probably in spite of the rampant patriotism. Twain did not love a parade.

In 1957, the 350th anniversary of Virginia's founding was called the Jamestown Festival, an event that attracted more than a million visitors, including Queen Elizabeth II of England. It was her first visit to the United States. There is no recognized term for a 350th anniversary.

Nor is there an authentic Latinate name for a 400th anniversary, though tetracentennial, quadricentennial, and quatrecentennial all have plausible etymological pedigrees.

For humanity, the cognitive feat of noticing the existence of time and then inventing a calendar to understand and control it was huge. But when those calendars began to be dotted with anniversaries and heroes and stirring events, something else had its start. History.

Still, history is more than a list of dates and names. History is breaking bread with the dead and asking them not only "What?" but "Why?" Interpretation and imagination are the next stages in brain power. But these are risky skills; open to mistake and miscalculation, though more rewarding than mere chronologies. That is, history may start with dates, but it can never end there.

The downside of anniversaries is that they can inoculate us against the new and surprising elements in the past. Alan Bennett's latest play, The History Boys, has it just right: "The best way to forget something is to commemorate it." That is, grand celebrations tend to put people to sleep intellectually.

A way out of the dilemma, as we contemplate Jamestown 1607, is to concentrate on our common humanity. As the World War I poet Laurence Binyon noticed in "For the Fallen":

They shall growIn history, as in everything, it's the thought that counts.

not old, as we

that are left

grow old:

Age shall not weary them, nor the years contemn.

At the going down of the sun and in the morning

We will remember them.

The Queen's Visit to Jamestown in 1957 Slideshow

The Queen's Visit to Jamestown in 1957 Zoomable Slideshow (requires Flash)

Silent video of the Queen’s 1957 Colonial Williamsburg visit (requires Quicktime)

Michael Olmert wrote "Why History?" for the summer 2004 journal. In 2006, he won his third Primetime Emmy for a documentary on the Discovery Channel. He teaches English at the University of Maryland.