The Restoration of James Madison's Montpelier

by Edward A. Chappell

Editor's note: The architectural restoration of Montpelier, the rural Virginia Piedmont home of James and Dolley Madison, is among the most complex and fascinating of our generation. It raises issues about preservation and presentation of historic buildings, sets a standard for the capture and synthesis of data, and offers a new glimpse of the Madisons' private lives.

James Madison Sr. built the Georgian house at Montpelier about 1760. His son expanded it for himself and Dolley Madison, and added a portico about 1797. As president, the younger Madison recast the center and added private wings at the ends. William duPont remodeled and enlarged the house in 1901.

Montpelier had grown into an almost incomprehensible behemoth. The Madisons twice expanded it. There were mid- and late nineteenth-century alterations. And when the wealthy William duPont Sr. bought the home in 1901, he enlarged it from thirty-six rooms above the cellar to 104. He also raised more than 100 structures on the grounds, including a general store. Two of the house's first-floor spaces remained in their Madison-era form.

The National Trust for Historic Preservation, which in 1984 became Montpelier's ninth owner, asked Colonial Williamsburg's architectural research department in 1997 for help understanding how the house had evolved, and how, renovation to renovation, it had looked.

Scholars and architects had studied Montpelier three times since 1977. The trust wrote a report that included records of nineteenth-century builders and visitors. But a broad understanding of Montpelier was elusive until Colonial Williamsburg architectural historians began investigations. Looking for evidence, they, among other things, made incisions through twentieth-century plaster to see the fabric behind. The exploration showed Montpelier comparable to Mount Vernon and Monticello in the complexity and personality of its changing form, though much of its early finish seemed lost.

Funds being limited and there being no rush, Colonial Williamsburg staff spent a little more than three weeks at Montpelier during the next four years. By 2001, Willie Graham, Mark R. Wenger, Carl Lounsbury, and I, expanding on earlier work, developed a physical history of the house.

James Madison's father built the original two-story brick Georgian house about 1760, and moved his family a half-mile from a smaller wooden dwelling called Mount Pleasant. Their new home had formal, symmetrical facades, with five vertical rows of openings on the face and three on the rear, including doors into opposite ends of a central passage. Rooms were stacked two deep. The builders put a parlor and dining room at the front. These two reception rooms with carved English red sandstone mantels were the best finished spaces. A narrow stair was enclosed between the passage and a rear bedchamber. Slaves prepared meals in a separate kitchen and, perhaps through the rear bedchamber, carried them to the dining room.

In 1797, retiring from Congress, Madison moved to Montpelier, and for himself and wife, Dolley Payne Madison, grafted a second residence onto the side of his parents' house. The addition looked and functioned much like an urban rowhouse of the era, with a side stair passage providing access to two rooms on each floor. We suspect there were a parlor and dining room downstairs, and bedchambers upstairs. Workers cooked food in a separate kitchen and brought it up through a cellar stair. There was no connection between the young peoples' and the parents' quarters. There was, in Wenger's words, "a fire wall between the generations."

Plans show how James Madison added a separate household to the left of his parents' house, then recast the center to create a drawing room and added bedroom wings. William duPont changed all but the two central spaces.

The arrangement required them to walk outside to visit next door. Madison resolved this by building a large portico with four Tuscan columns carrying a pediment that sheltered both front doors. Though oddly proportioned, it gave a central focus to the house and masked the unconventional organization of openings. Light colored, the porch looked handsome against the red brick walls. But the portico blocked much of the view from the best rooms upstairs, so the retired congressman had to sit or lean over to see the Blue Ridge Mountains.

In 1809, the year after he was elected president and eight years after his father's death, Madison turned the house into a proper seat for a chief executive, his wife, and mother. The change had more to do with shifting functions than size, though it included two wings. Physical evidence and the accounts of builders James Dinsmore and John Neilson taught us much about the construction.

This second remodeling joined the two parts of the house, maintaining separate quarters for the generations. The parlor and a left-hand chamber were gutted to create an entry lobby in front of a substantial drawing room—a reception space finished with classical woodwork, and furnished with patriotic and pedagogical art. Thomas Jefferson, Madison's architecturally energetic mentor, recommended making the room more expansive by raising the ceiling and rebuilding the rear masonry wall to create a bow. Madison quietly resisted; the cost and inconvenience were prohibitive.

Guests could enter the lobby from the porch through a new central doorway surrounded by glass. Family or servants would escort them into the drawing room or one of the older passages—the widow Nelly Madison's on the right or the president and his wife's on the left. Beyond were the widow's rooms, or the couple's dining room on the opposite side. Nelly Madison lost little space in the remodeling and no status, but her spaces were old-fashioned compared to the stylish drawing room and the quarters to the left.

The remodeled house can be read as an accommodation for the women, as well as the president. Dinsmore and Neilson built two single-story wings in 1809-12, containing the house's most refined private spaces, and making it thirteen bays long. On the right, Nelly Madison walked from her receiving room through a dark closet and lobby into a large new bedroom. On the left, the couple walked from its dining room through an equally dark lobby to a comparable bedroom. By 1832, Dolley Madison occupied the left wing alone, and the ailing ex-president stayed in their old rear room, behind the dining room.

There were new cellar kitchens, directly below Nelly and Dolley Madison's bedrooms, with access up stairs from open cellar passages to the lobbies connecting both pairs of bedroom and dining room. Clay insulation was packed between the floor joists against the kitchens' sounds and smells. No other floors were so insulated. The wings were covered with railed decks, and the Madisons and their guests could reach at least the left one from the second story.

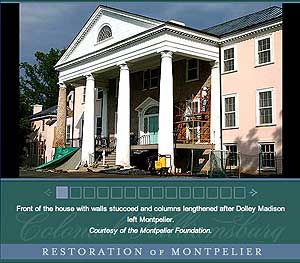

Later nineteenth-century remodelings attempted to make the portico more academic and monumental by recessing the porch floor and carrying the masonry columns to the ground. More sensible pitched roofs were built over the wings. A grandiose marble mantel replaced the plainer Roman one in the drawing room, and walls were hung with colorful papers.

Marion Scott created her modern "Red Room" from Nelly Madison's bedroom. Nelly Madison entered her private wing through the small doorway to the left of a ca. 1760 stone mantel, in what became the duPont smoking room.

At the turn of the century, duPont bought Montpelier for his and his wife Anna duPont's principal residence. He set about, without much apparent help from architects, remaking it into an estate with a baronial country house. He paid some respect to the perceived style of the house, especially its neoclassical woodwork, but recast its arrangement.

On the first floor, the 1809-12 lobby and drawing room retained their shapes, though doorways were altered and the circulation pattern changed. James and Dolley Madison's dining room was combined with part of their stair passage to become a billiard room. Her bedroom became a secondary kitchen and service corridor. Nelly Madison's reception room was expanded for a smoking room. Three new reception rooms with European neoclassical finish were created at the right end of the house, one of them occupying Nelly Madison's 1809-12 wing. Both wings were raised to two stories and extended in an asymmetrical composition. The enlarged portico was retained to help clarify the intended center of the house.

Daughter Marion duPont inherited use of the property in 1928, and lived there until her death in 1983. A horsewoman, she married cowboy actor Randolph Scott in 1936, and the couple made Nelly Madison's cellar kitchen into an exercise room for him. Upstairs, she created the "Red Room," a modernist lounge with chrome and white-trimmed red sofas, an Art Deco glass fireplace, and hundreds of photos of her prize-winning horses and jockeys. It replaced her parents' Empire drawing room and took the full main floor of Nelly Madison's wing.

Marion Scott bequeathed Montpelier to the National Trust with a wish for its Madison-era restoration. Short of operating funds, a series of directors maintained and presented the property to small numbers of visitors. Staff struggled to explain Madison's Montpelier in what was a 1901 country house with its furnishings removed.

In 2000, the Montpelier Foundation became steward of the property. That year, trust president Richard Moe and the new foundation president Michael Quinn began discussing restoration with the executors of philanthropist Paul Mellon's estate. They paid for nine months of architectural and archaeological exploration and a feasibility study. Quinn assembled a research team led by Colonial Williamsburg staff, primarily Wenger and Myron Stachiw, with help from Willie Graham, Peter Sandbeck, and others. Joining them were Montpelier staffers John Jeanes, Ann Miller, and Alfredo Maul. The architectural firm Mesick, Cohen, Wilson, and Baker developed a restoration schedule and cost estimates.

Mellon funding accelerated investigations. More attention was turned on the building in a week than we had given it in a year. By 2002, the team had learned much and developed an expandable approach to recording every layer in every small exploration through the strata of paint, plaster, and woodwork in all the Madison spaces.

The restoration implications of the discoveries were small and large. It was known that the 1809-12 drawing room opened into the circa 1760 passage. The connection was a doorway between James Madison's new reception space and his mother's apartments, a doorway closed in 1901. Earlier investigation found edges of the opening, but nothing about its form. Wenger and Stachiw peeled off layers of wallpaper and plaster above, and Stachiw found a thin dark line left by a painter who had inadvertently marked the outline of the pediment installed by Dinsmore and Neilson. The reused paneled door and parts of the frame were found elsewhere. So the shape of the pediment as well as color of the trim and door was established for the best room in the house.

It was long believed that Madison stuccoed the house when he added the wings. The explorations in 2001 uncovered evidence that the brickwork remained exposed after Madison's death, probably until about 1858. This was sobering because it meant removal of all the stucco from the brickwork of all three phases, much of which was damaged, to fulfill Marion Scott's wish.

Reporting such findings in ten volumes, the team built a case that much more could be learned about the state of the house when James, Dolley, and Nelly Madison lived there—enough for a restoration more accurate than imagined.

Whether to restore Montpelier at all was much debated. Since the 1960s, most architectural historians have favored a cautious, antiscrape approach to most historic buildings. Preserving layers of change lets buildings tell more complex stories, and retain the character they have developed—while avoiding the guesswork any restoration includes. Restorations have often left important buildings less evocative than they were before the scraping.

The Montpelier Foundation made the more dangerous and exciting choice to restore the house to the period between 1815 and Madison's death in 1836. Mellon funds are to pay for most of the restoration. The foundation is to raise more for furnishings and some construction. The completion date is 2008. Movable pieces of the duPont's neoclassical reception rooms and the Red Room are to be reassembled where the family is presented elsewhere on the property.

The next step was a full recording of the duPont additions, followed by demolition that revealed much Madison material salvaged in 1901. Though we knew about flat decks over the 1809-12 wings, we could only guess how these parts were roofed. Removal of duPont bathroom tiles showed the outline of small parallel rooflets, like those at Jefferson's Monticello. Distinctively shaped joists used to frame these roofs were found in duPont additions to the bowling alley.

A Philadelphia photography collection produced a nineteenth-century picture of James Madison's bedroom, showing a narrow door, previously unknown, between his room and Dolley Madison's dressing chamber in the wing. Maul and Wenger followed this lead and found the door itself—the masonry opening and the six-panel leaf, reused elsewhere in 1901. This reveals much about the private life of the Madisons, suggesting that by 1812 the couple may have occupied separate chambers joined by a private route, through dressing chamber and lobby, in addition to a public route through the dining room.

Maul,

Wenger, and their colleagues have developed means of recording all such

evidence in digital drawings, photographs, and hybrids. The scope of their

information makes traditional drafting and photography techniques insufficient.

The group uses electronic methods for presenting, recording, and archiving the

data.

The

Montpelier team is setting a standard for architectural research. It indicates

how cautiously we should move when exploring or "restoring" the old family

house. Montpelier's state-of-the-art restoration may strengthen the argument

for leaving most historic buildings with their layers of change intact.

Edward A. Chappell, a long-time journal contributor and Colonial Williamsburg's Shirley and Richard Roberts architectural historian, wrote "The New Architecture of Merchants Square" for the summer 2004 journal.

For more information: