Alas, Poor ...Who?

Or, Melancholy Moments in Colonial and Later Virginia

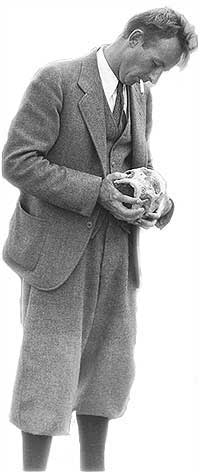

by Ivor Noël Hume

Unlike Hamlet, rarely do we know him well. Archaeologists examining human remains seldom know the subject's identity. We clean up the bones with all the care of a funeral director and try to determine age, sex, height, and any other detail we can glean from the grave. I well remember cleaning the teeth of an open-jawed individual killed at Martin's Hundred—an early Virginia settlement—during an Indian uprising on March 22, 1622. I asked myself: What were his last words? If only I could, for an hour, interview him about his life, his hopes, and his fears. I could only wish, and wonder.

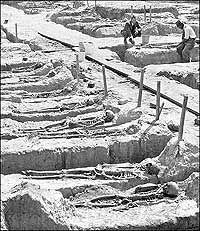

At Jamestown, the first permanent English settlement in America, roughly a hundred yards from the site of the fort the colonists built, there are about fifty graves. Set in an area known in the seventeenth century as No Man's Land, this cemetery was thought to hold the dozens who died in what is called the Starving Time, the winter of 1609-10. They were people who could at least be identified by the common calamity that killed them, and some of their names are known. But recent excavations by the Jamestown Rediscovery team showed some burials cut through others, making it clear that not all the people were interred at the same time.

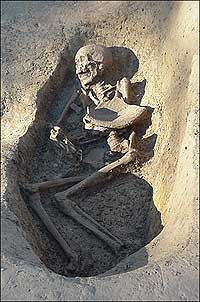

More closely dated were the Indian attack victims at Martin's Hundred. We think one was Lieutenant Keane. Five others are known to us only as four servants and a maid, the extent to which they were identified in the list of the dead sent to London. In no instance had the deceased the nicety of a coffin or, as far as we could tell, a shroud.

Four or five years later a cemetery was established adjacent to the plantation of Martin's Hundred governor, William Harwood. There, for the first time, we found the remains of coffins as well as brass pins that had secured shrouds and chin straps. All that remained of the coffins were the nails, some of them in a line down the center of the deceased. It took a while to be sure what they were doing there. Coffins, as we thought we knew them, had flat lids and no need of center-line nails. The solution was simple enough once we figured it out. The lids were shaped like an uncrossed "A," the two lapping boards secured with nails. Research showed A-lidded coffins were common until the late seventeenth century.

Little documentary evidence survives to tell us about the ritual and process of interment in the 1600s. A skeleton discovered in the Jamestown fort, however, lay with a pike-headed staff beside him, evidently a mark of officer status. As a rule, however, Christian burials rarely include what archaeologists call "grave goods." An exception was one I found in London, containing a fine English delftware plate of about 1680 carefully inverted over the man's abdomen.

All but one of Martin's Hundred's massacre victims were found in proper graves and presumably were interred with ceremony. Virginia's critics said such care was by no means universal. Writing in 1623, ex-governor of Bermuda Nathaniel Butler reported that many new arrivals—people weakened by the Atlantic crossing, the change in climate, or by New World contagions—were "not only seen dyeing under hedges & in the woods but beinge dead ly some of them for many dayes Unregarded & Unburied." Residents of the colony countered: "As for dyine under hedges ther is noe hedge in all Virginia." If that sounds like a politician's half-answer, it probably was.

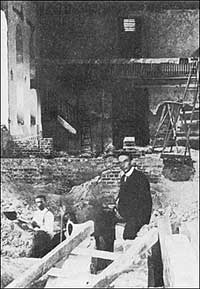

Excavations in Williamsburg's Bruton Parish churchyard in the 1930s uncovered an early church foundation, as well as ancient graves.

People undoubtedly wandered into the forest to die. During the Starving Time, a report said, "Some adventuringe to seeke releife in the woods, dyed as they sought it, & weare eaten by others who found them dead."

It is evident that in seventeenth-century Virginia the dead were not regarded with the reverence that would be theirs in more recent times. In 1661 the colony's General Assembly thought it necessary to formulate a law to discourage "that barbarous custome of exposing the corps of the dead to the prey of hoggs and other vermine." The aim was to prevent people secretly disposing of their dead in shallow and unmarked graves, perhaps hiding the evidence of foul play. The statute required every parish to provide three or four spaces to be fenced for "publique buriall." No longer was it permissible to dispose of Aunt Agatha in a hole dug in the woods.

In 2003 archaeologist Al Luckenbach of Maryland's Lost Towns Project found in the floor of a cellar filled with domestic trash in the 1660s a grave so shallow the remains were scarcely covered. In it lay a fifteen-year-old boy with a large fragment of a ceramic dish and other refuse dumped atop him. Evidently, someone thought it prudent to dispose of the body immediately before the cellar was filled. The cause of death has not been determined.

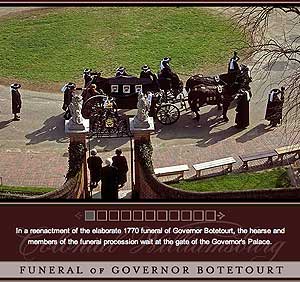

Colonial Williamsburg re-created the funeral of Governor Botetourt, complete with hearse and pallbearers departing the Governor's Palace.

Formalizing the places of public interment also ensured that the public paid attention to the burial process. About 1680 colonists began to erect headstones and other such memorials over or beside graves. Nevertheless, they seem to have consigned most of the dead to unmarked graves. Archaeologists have searched for signs of even wooden crosses having been hammered into the ground at their heads, but no telltale holes have been reported.

This was not true of the colonial gentry, whose existence was invariably thought worthy of remembrance. By the late sixteenth century inscribed slabs, called ledger stones, were set in the aisles of churches, and when the space below them was full, the dead and their stone markers were sent outside—as was the case in Williamsburg's Bruton Parish, where even a deputy governor was entombed outside the church.

The Jamestown church-yard contains elevated table tombs dating from the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, a reminder that the church, a picturesque ruin by the nineteenth century, rang to the singing of hymns as late as 1758. Inside today's reconstructed church visitors can see a stone slab chiseled to receive monumental brasses. Such decorations were common in medieval churches in England until they were stolen by Puritan troops during the English Civil War. A similar fate befell the Jamestown grave markers, though nobody knows who took them. It is believed the stone covered the grave of Governor Sir George Yeardley, who died in 1627.

Floor-level gravestones for gentry became common in English churches in the sixteenth century, but not until the late seventeenth century did vertical headstones become popular for those buried outside. In Virginia when plantation owners were interred on their estates, table tombs, elevated brick-walled and stone-veneered boxes built above ground, gave the grave site prominence and kept weeds from growing over the markers. The earliest recorded flat grave marker, however, is reputed to be that of Colonel William Perry at Westover, who died in 1637.

Table tombs were not containers for the deceased, as treasure-seeking grave robbers have supposed, but covered the grave four to five feet below. The markers for members of the Page family of Rosewell are among those that fell victim to vandalism and were moved to safety in the nearby Ware churchyard. A fine example of one that escaped such sacrilege, however, is that of John Custis IV at Arlington, who died in 1749 on Virginia's Eastern Shore.

Custis was a meticulous, eccentric, and suspicious man. In his will he ordered a tombstone from England and instructed his heir to send for another if the first did not arrive. Furthermore, his son was to see to it that it really was his father who was being returned to Arlington "and not a sham coffin."

As today, coffins came in grades and complexities reflecting real or supposed wealth or social status. The poorest families rented the reusable parish coffin and went to their Maker in no more than a winding sheet. The simplest wooden coffins were of pine, often covered with fabric secured with black-painted brass tacks. But if one were as cautious as John Custis, the inner coffin would be of elm lined with fabric, this encased in lead of a thickness having a ratio of five pounds per square foot. With the lead sarcophagus sealed, a memorial depositum plate in tin or brass would be attached before it was encased in an outer shell of elm or oak. That done, the whole weighty box would be covered with scarlet or black velvet secured with rows of round-headed brass tacks.

When Virginia's Lieutenant Governor Lord Botetourt died in Williamsburg in 1770, he got the two-layer treatment, a pine inner coffin "& one of lead Covered with Crimson Velvet, with a plain plate upon it of silver bearing his Name age & death." His funeral, however, afforded him the full treatment. Streets were lined with the militias of the town and the counties of York and James City. Eight professional mourners, two ahead, and three on either side of the hearse, led the procession of dignitaries, clergy, college professors, servants, and students, all wearing white hatbands and gloves. Behind the formal procession walked the townspeople, two by two.

Those of the living who daily were confronted with death and sorrowing relatives could be expected to become inured to grief. Like Hamlet's grave digger, sextons regularly cut through the occupant of one grave to add another, and it is a common sight in English churchyards to see human bone fragments littering the flower beds. Unseen by the congregation, the passages to crowded private vaults are found with the ends of the last coffins jammed, half in and half out of the doorway. What the eye did not see, the heart truly could not grieve over. Nevertheless, there were individuals like John Custis who, while alive, were fearful that they might not be left alone to await the last trump. Worse yet, they might not be dead.

Perhaps encouraged by such writers as Richmond's Edgar Allan Poe, fear of being buried alive became a pervasive phobia in the second half of the nineteenth century. Embalming, therefore, provided the ultimate reassurance and became increasingly popular as the century progressed. The funeral of Abraham Lincoln, and the need to keep him on display for two weeks, called for some hasty reevaluating of the embalming process and the safeguard of hiding large blocks of ice under the bier. Even so, while still on the train to Illinois, his body turned black.

If embalming was not to be one's preferred means of being certifiably dead, several other safeguards were patented in the United States, among them a ground-reaching shaft attached to the top of the coffin with a bell on it and an escape ladder to get there. A trifle more modest was Albert Fearnaught's Indianapolis patent of 1882, which allowed for a flag to pop up through a tube if the occupant moved a hand.

In England and the United States at the close of the eighteenth century mourning became an elaborate ritual in dress and etiquette. The front parlor was set aside for the purpose; such potters as Wedgwood produced tea services in black basalts with teapots with weeping women on their lids. Silk weavers whose business had been declining boomed again. Black crepe was hung in festoons around the coffin, from the skirts of the hearse and around the hats and staffs of the somber mutes who were part of the show.

In the eighteenth century it had been common for middle-income heirs to conduct funerals in the evening, when processions could be smaller and cheaper without being noticed. In the early nineteenth century the families of even modest craftsmen and tradesmen felt compelled to send their relatives to their graves in processions that made sure they did not pass their neighbors overlooked. By the second quarter of the nineteenth century, however, according to one writer, "Already under way was a gradual drift in mood from gloom to beauty."

At the same time the traditional coffin began to be replaced by elaborately shaped sarcophagi that became the genesis of the modern casket. Early in the nineteenth century cast iron began to be used for everything from bridges and erector-set buildings to chairs and railings. It was not long before coffins joined the inventory, and in 1836, James A. Gray of Richmond obtained an American patent for a metallic coffin. More successful, however, was Almond D. Fisk, whose Metallic Burial Case went into production in Providence, Rhode Island, around 1848 and whose company was acquired by Crane, Breed and Co. of Cincinnati in 1853.

Fisk's castings came in shapes ranging from an Egyptian mummy to something resembling a deep-sea diver. Common to all was a glass window at the head, not to enable the deceased to look out but to let relatives look in. Fisk said the tightly sealed cases "may be filled with any gas or fluid having the property of preventing putrefaction." The intent was to preserve the remains of people who died far from home more or less intact until such time as they could be brought back for the family funeral. And it worked, as I was to discover one afternoon in Williamsburg.

Called by Colonial Williamsburg security to a trench being dug behind the site of the Public Hospital, I was shown one of Fisk's patent cases hanging half out of the side of the excavation. A back hoe had snapped off its feet. The operator had sent his assistant into the ditch to see what had fallen out. He was last seen heading for Newport News.

More Fisk-type coffins have been found in the neighborhood, one near Colonial Williamsburg's windmill, another in woods near Newport News, and another in 1993 beside the Colonial Parkway outside Yorktown. Heavy and relatively costly though the Cincinnati castings were, they seem to have been popular in antebellum Virginia.

When senator and secretary of state John C. Calhoun died in 1850 and was entombed in the Congressional Cemetery, Jefferson Davis, Henry Clay, and Daniel Webster were persuaded to write a published endorsement declaring the Fisk Metallic Burial Case to be "the best article known to us for transporting the dead to their final resting place." The nature of the persuasion is not recorded.

The growing preference for durable burial cases—made of materials that could range from terra-cotta to glass—curtailed the work of town cabinetmakers, who through the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries traditionally augmented their businesses by creating made-to-order coffins. Worse was to follow when the less costly expedient of cremation took hold.

At first, the deliberate destruction of the remains was anathema to traditionalists, but the necessities of speedy disposal of epidemic victims hastened a rethinking.

My only encounter with modern cremation was generated by another call from Colonial Williamsburg's security staff. This time it was to investigate a scattering of human bones found lying on the lawn behind the bedrooms at Providence Hall, a wing of the Williamsburg Inn. A trail of gray bone ash spread across the grass into an equally ash-dappled shrub. Under it lay an open, gold-painted canister. There could be no doubt that it had been thrown out of a hotel window.

Needless to say, I made no effort to ask, "Alas, poor who?" It was more than sufficient to know that the ashes of a middle-aged lady had been propelled to her rest in a flower bed. How did I know that she had been a middle-aged lady, you might ask?

To this I can only reply that I have long been a disciple of Sherlock Holmes, whose methods were a constant amazement to Dr. Watson.

Williamsburg-based Ivor Noël Hume contributed to the winter 2005 journal a story about Jamestown's Dr. John Pott.