Online Extras

Newspaper Advertisements Slideshow

“Sold on Reasonable Terms”

Early American Newspaper Advertisements

by Jack Lynch

Journalists are worried. Hardly a month goes by without another newspaper going broke. There’s a website, NewspaperDeathWatch.com, which chronicles the demise of once-thriving dailies and weeklies. The problem is the breakdown of the business model on which papers depended. The subscription fees of most newspapers never paid all the bills; papers need advertisers to cover their expenses. And as the advertisers abandon the papers for other media, the papers fight for survival.

Advertising has been part of the newspaper business since it began in England at the end of the seventeenth century, and was essential to the earliest papers in North America. Massachusetts residents who in 1704 read the first issue of the Boston News-Letter—the first newspaper in the colonies—would have seen this paragraph:

This News Letter is to be continued Weekly; and all Persons who have any Houses, Lands, Tenements, Farmes, Ships Vessels, Goods, Wares or Merchandizes, &c. to be Sold or Lett . . . or Goods Stole or Lost, may have the same Inserted at a Reasonable Rate; from Twelve Pence to Five Shillings and not to exceed.

A week later, a subscriber responded by placing an ad seeking to recover lost property: “Lost on the 10. of April last off Mr. Shippen’s Wharff in Boston, Two Iron Anvils.” The advertiser apparently had no luck with this, the first classified ad in America, because the same notice appeared a week later. This time, though, it was accompanied by a real estate opportunity too good to pass up: “At Oysterbay on Long-Island, in the Providence of N. York, There is a very good Fulling-Mill, to be let or Sold, as also a Plantation, having on it a large new Brick house.” The newspaper business and the advertising business got under way together.

As the years passed, ads became ever more common. A reader who picked up the Virginia Journal and Alexandria Advertiser for February 12, 1784, for instance, would find advertisements on three of its four pages. William Hartshorne and Company took up more than half of the front page with offers for “Printed cottons and calicoes, Ladies’ hair-pins, Artificial flowers, Corks and cheese, Candles by the box, Neat pocket volumes of poetry, Bibles, testaments, prayer-books, and spelling-books, Sail-cloth from number 1 to 8, Coopers axes and adzes, Copper teakettles and coffee-pots, Sweet oil in bottles, Black pepper,” and “Loaf sugar.” The firm also advised delinquent customers: “Those indebted to said HARTSHORNE and COMPANY; would do them a singular kindness in making payment at this time, as they are desirous of extending their trade.”

On the next page James Adam touted “fine Ship-Bread of a good quality,” and Alexandria’s Printing Office offered “ALMANACKS, For the Year of our LORD, One Thousand Seven Hundred and Eighty-Four.” On page 3, Robert Allison drew attention to his “BROADCLOTHS, shalloons, durants, calamancoes, coat and vest buttons, sleeve ditto, twist, sewing silk, knives and forks,” which he was willing to part with “for CASH, TOBACCO, HEMP or FLOUR.” And on page four, right after a poem and a morally improving essay, appeared advertisements from four other firms, all offering groceries and dry goods.

Sometimes these advertisements seem quaintly antiquated. Cooper’s axes, shalloons, and ship-bread, after all, aren’t promoted in many modern newspapers, and you can’t trade hemp or flour for goods today. Colonial ads were almost always local, placed by retailers rather than manufacturers, since there were no national brands. There wouldn’t be an advertising agency in America until 1841, when Volney B. Palmer opened a shop in Philadelphia.

Still, despite the differences, it’s hard to shake the sense that these 250-year-old ads are familiar. We find in them the same mix of businesses that marks advertisements today. Those who’ve seen infomercials hawking patent remedies will be at home with this announcement from the Pennsylvania Chronicle in 1772:

Dr. George Weed . . . hath to sell a neat assortment of medicines, among which are; The Royal Balsam Syrup against the bloody flux; Syrup of Balsam, against coughs and colds; Bitter Tincture, for the head and stomach; Ointment to cure burns and scalds; Ointment and Powder to cure the piles, Ointment to cure inflamed Eyes. Printed directions will be given with each of them with their particular virtues. He can with pleasure acquaint the public, that the success of these medicines hath been so great, there is a continual sale of them.

Here we can see the origins of perennial advertising practices—extravagant promises accompanied by a warning that purchasers must act soon, lest the good doctor sell out before they’ve found relief.

Much about these advertisements—breathless hyperbole, extravagant promises—is familiar to modern eyes. But a common class of ads reminds us at once that their world is not ours. That first issue of the Boston News-Letter not only welcomed advertisements for “Wares or Merchandizes, &c. to be Sold, or Let . . . or Goods Stole or Lost,” but it also invited notices of “Servants Run-away.” And we have to remember that, to eighteenth-century sensibilities, the “Wares or Merchandizes . . . to be Sold” included human beings.

Early American newspapers bristled with ads about slaves. Promotions of sales, whether of individual slaves or “parcels,” were common. The Boston News-Letter for March 12, 1710, for instance, ran a series of advertisements—“All sorts of Cables and Anchors for Sloops, Good green Tea, Pomcitron, wet sweetmeets, Luke Olives”—followed by this notice:

A Likely Negro Man about 18 years of Age Speaks good English and served some time to a House Carpenter, To be sold: Inquire at the Post- Office in Boston and know further.

Alongside announcements of sales were offers of rewards for capturing enslaved persons who had escaped their owners. This one from Williamsburg’s Virginia Gazette, November 5, 1736, is typical:

RAN away Two Negro Men Slaves; One of them called Poplar, from my House in King William County, some Time in June last; He is a lusty well-set likely Fellow, of a middle Stature, upwards of 30 Years old, and talks pretty good English: The other called Planter, from my plantation in Roy’s Neck, in the County of King and Queen, about the Month of August following. He is a young Angola Negro, very black, and his Lips are remarkably red. . . . N.B. The Negroe Poplar is Outlaw’d.

What may be most revealing is usually left unspoken in the ads themselves. The language of marketing brings home, in a way statistics cannot, just how much slaves were viewed as commodities. Not only were enslaved people advertised alongside hairpins, teakettles, and candles; sometimes they appeared in the same ad. This paragraph from the Charleston Morning Post for August 23, 1786, for example, ends with a jarring postscript:

Gambia negroes.

JUST arrived in the sloop Good

Intent, Capt. Garner, from

Africa, a few of the finest young

SLAVES,

ever imported into South-Carolina, to be sold, for

cash or produce, on board the sloop at Prioleau’s

wharf.

J. & E. Penman,

No. 75, Bay,

Who have also for Sale,

A few bags of COFFEE,

and Cases of LIQUEURS.

The Georgia Gazette of October 20, 1763, announced goods on sale after the arrival of a ship from Jamaica:

About nineteen valuable new NEGROES, muscovado sugar by the tierce or quarter cask, Jamaica rum . . . bottled ale and cyder, coffee, &c. to be sold on reasonable terms.

And the Maryland Journal of July 4, 1786, offered

NEGROES, HORSES, CATTLE, HOUSEHOLD FURNITURE, and other articles too tedious to mention.—Three months credit, from the time of sale, will be given the purchasers, on giving good security.

Coffee, rum, cider, horses, furniture, and slaves, a list the dealers found “too tedious to mention,” all available on reasonable terms.

Hardly an issue of a newspaper appeared without an ad about a runaway. The weekly South-Carolina Gazette included seven notices of escaped slaves in May 1783, and there were ninety-eight in the Virginia Journal, another weekly, in 1785.

Early Americans got their news in a package that bundled current events with promotions of the slave trade. Sometimes the juxtapositions between news items and ads could be striking. July 11, 1776, subscribers to the New-York Journal read for the first time the text of the Declaration of Independence, with its provision that “all men are created equal.” But when they turned the sheet over, they saw a page of such advertisements as: “TEN DOLLARS Reward. RUN AWAY from the subscriber on Thursday the 20th instant, a negro man named JACK . . . FIVE DOLLARS REWARD. RUN AWAY from the subscriber on the 16th instant, a negro man, named PRINCE . . . ONE DOLLAR Reward. RUN AWAY from the subscriber . . . a negro man named SAMSON, about 50 years of age.” A few days later, Boston’s Continental Journal devoted page one to the text of the Declaration, but page four included these notices:

A Negro Woman. TO be SOLD, a likely young Negro Woman that understands House-work, common Cooking, &c., has had the Small-Pox.

EIGHT DOLLARS REWARD. RAN away from the Subscriber . . . about 5 Weeks ago; a Negro Man named Cato, about twenty-five Years of Age . . .

N.B. The above Negro was seen one day last Week at Lanesborough, and is a sly Rogue, and whoever takes him, is desired to be careful of him.

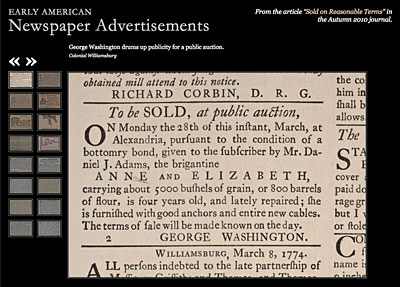

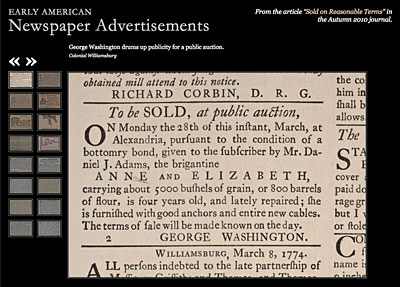

The names that appeared beneath the advertisements can also catch our attention. This ad, from the Maryland Gazette of August 20, 1761, for instance—

RAN away from a Plantation of the Subscriber’s, on Dogue-Run in Fairfax, . . . the following Negroes, viz.

Peres, 35 or 40 Years of Age, a well-set Fellow, of about 5 Feet 8 Inches high . . .

Jack, 30 Years (or thereabouts) old, a slim, black, well made Fellow, of near 6 Feet high, a small Face, with Cuts down each Cheek . . .

Neptune, aged 25 or 30, well-set, and of about 5 Feet 8 or 9 Inches high, thin jaw’d, his Teeth stragling and fil’d sharp . . .

Cupid, 23 or 25 Years old, a black well made Fellow, 5 Feet 8 or 9 Inches high, round and full faced, with broad Teeth before, the Skin of his Face is coarse, and inclined to be pimpley . . .

—seems unremarkable until the last paragraph, which reads,

Whoever apprehends the said Negroes, so that the Subscriber may readily get them, shall have, if taken up in this County, Forty Shillings Reward, beside what the Law allows; and if at any greater Distance, or out of the Colony, a proportionable Recompence paid them, by

George Washington.

The Virginia Gazette for September 14, 1769, included this:

RUN away from the subscriber in Albemarle, a Mulatto slave called Sandy, about 35 years of age, his stature is rather low, inclining to corpulence, and his complexion light . . . He is greatly addicted to drink, and when drunk is insolent and disorderly, in his conversation he swears much, and in his behaviour is artful and knavish . . . Whoever conveys the said slave to me, in Albemarle, shall have 40s. reward, if taken up within the county, 4 l., if elsewhere in the colony, and 10 l. if in any other colony, from

Thomas Jefferson

These ads remind us that the slave trade was a business that depended on marketing, and that many early Americans viewed slaves as another commodity. But they can be illuminating. They often give details about what the slaves were wearing when they escaped, what trades they had learned, their proficiency in English—details rarely preserved in other records. Even the omissions can reveal things about the state of enslaved people in the colonies and early republic. The ages the ads give are almost always approximate—“about 18 years of Age,” “upwards of 30 Years old”—suggesting that the slave owners could only guess, presumably because no birth records had been kept.

Historian Jonathan Prude writes: “Runaway ads invariably stand as extraordinary documents. Almost unmanageably rich in detail, they provide brisk but arresting portraits of people drawn mainly from the anonymous ‘lower sort.’ . . . The ads thus inform us about constituencies about whom scholars know little.”

A little idle browsing through some early American advertisements can enlighten the social historian, professional or amateur, because they help put together a portrait of an age with clues not preserved elsewhere in the historical record.

See more ads from the article in our "Early American Newspaper Advertisements" Slideshow.

Jack Lynch, author of Becoming Shakespeare: The Unlikely Afterlife That Turned a Provincial Playwright into the Bard (Walker & Co., 2007), is associate professor of English at Rutgers University. He contributed to the spring 2010 journal “‘His Integrity Inflexible, and His Justice Exact’: George Wythe Teaches America the Law.”

Suggestions for further reading:

- Tom Costa, “What Can We Learn from a Digital Database of Runaway Slave Advertisements?” International Social Science Review 76, nos. 1–2 (2001): 36–43. ———, “The Geography of Slavery in Virginia,” www2. vcdh.virginia.edu/gos/, a database of more than 4,000 advertisements for runaway slaves from 1736 through 1803.

- Jonathan Prude, “To Look upon the ‘Lower Sort’: Runaway Ads and the Appearance of Unfree Laborers in America, 1750–1800,” Journal of American History 78, no. 1 (June 1991): 124–59.

- E. S. Turner, The Shocking History of Advertising! (London, 1953).

- Lathan A. Windley, Runaway Slave Advertisements: A Documentary History from the 1730s to 1790, 4 vols. (Westport, CT, 1983).

- James Playsted Wood, The Story of Advertising (New York, 1958).