Theodor de Bry’s engraving shows a pumpkin patch, marked with an "I," at the center of a sixteenth-century Indian village.

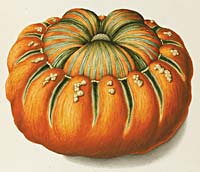

The motley of older varieties of edible pumpkins has shrunk to the monochrome, indigestible Halloween porch sitter of today.

Smoky Hill Bison Company

"Food in name only,” historian James McWilliams calls the bloated Halloween decorations we know as pumpkins.

Colonial Williamsburg

Fattening in the Virginia Tidewater summer, pumpkins are yet grown in the leafy shade of Colonial Williamsburg’s Historic Area.

Dried, stewed, roasted, baked, raw . . . served as side dish, dessert, drink, livestock feed, the pumpkin used to support man and beast.

A stuffed pumpkin appears as first course on the dining table in the family-focused Powell House on Waller Street.

Some Pumpkins!

Halloween and Pumpkins in Colonial America

by Mary Miley Theobald

Colonial Americans didn’t celebrate Halloween. They didn’t have jack-o’-lanterns either, or trick or treat, or costumes, or candy as we know it. What they had were pumpkins— large and small, round and oval, warty and smooth, squat and misshapen, orange, yellow, and green, far more varieties of the fruit than we see today, all of which they consumed in far greater quantities than we do today.

As America once again decorates its porches with grimacing pumpkins and braces for the annual onslaught of princesses and caped crusaders, one can’t help wondering what our forebears would have thought of these Halloween rituals. It seems likely that Indians and colonists alike would have been puzzled by the candlelit faces, aghast at the waste of good food, and appalled when they saw the smashed remains littering the streets.

In their day, the pumpkin, or pompion as it was called, got more respect. An important food source, pumpkins were crucial to their survival through the hungry winter months.

Though Halloween was unknown in early America, the established Church of England did take note of All Saints Day, also known as All Hallows’ Day, on November 1. All Hallows’ Evening, corrupted to Halloween, fell on the preceding night, October 31, but it was not an occasion for costumed children to rap colonial door knockers, and no jack-o’-lanterns flickered from colonial windows.

The origins of Halloween date back two millennia to the Celtic harvest festival Samhain, celebrated in November at the beginning of the Celtic New Year, when the souls of the dead were said to return to earth. Beliefs and celebrations varied from place to place, but often involved bonfires, burning sacrifices, and costumes, as people marked another autumn’s reaping and honored the dead. Pumpkins were unknown in Europe at this early date, but traditions included hollowing out gourds to make lanterns to light the way at night or, some said, to ward off evil spirits that roamed the countryside on All Hallows’ Eve. Irish immigrants brought Celtic traditions to America in the nineteenth century, where they found the pumpkins larger than gourds and better for carving. So, in the New World, their jack-o’-lanterns were made from pumpkins instead.

One of America’s oldest native crops, pumpkins were an important staple long before Europeans crossed the Atlantic Ocean and discovered them. Cultivated independently by the indigenous peoples of North and South America, pumpkins—or more accurately, pumpkin seeds—have been found at archaeological sites in the American southwest dating back six thousand years, as well as at sites throughout Mexico, Central and South America, and the eastern United States.

Evidently, seeds were the only part consumed by these ancient cultures because the flesh of most wild pumpkins was too bitter to eat. Once cultivation altered the pumpkin enough to make it palatable, Native Americans devoured every part of the plant—seeds, flesh, flowers, and leaves. Pumpkins and squashes of all sorts could be baked or roasted whole in the fire, cut up and boiled, or added to soup.

Removing the seeds, cutting the pumpkin into strips, and drying them—making a sort of jerky—effectively preserved them. Indians also dried the outer shells of pumpkins and squashes and used them as water vessels, bowls, and storage containers.

Almost every early European explorer commented on the profusion of pumpkins in the New World. Columbus mentioned them on his first voyage, Jacques Cartier records their growing in Canada in the 1530s, Cabeza de Vaca saw them in Florida the 1540s, as did Hernando de Soto in the 1550s. In the 1580s, Thomas Hariot, scientific adviser to the Roanoke expedition, realized early on that the multitudes of colors and shapes were actually quite similar in taste. He wrote, “Severall formes are of one taste and very good, and do also spring from one seed.” Captain John Smith described in 1612 how the Powhatans grew pumpkins near Jamestown. Pumpkins and related squashes were an indispensable part of the diet for Native Americans of all regions.

A few Europeans also described how the Indian women prepared their pumpkins. Peter Kalm, a Swedish botanist who explored the wilds of New York and Canada, wrote in 1749:

The Indians, in order to preserve the pumpkins for a very long time, cut them in long slices which they fasten or twist together and dry either in the sun or by the fire in a room. When they are thus dried, they will keep for years, and when boiled they taste very well. The Indians prepare them thus at home and on their journeys.

Sounds simple enough, but when George Washington directed his farm manager to do this with Mount Vernon’s pumpkins, the man reported failure. “I tried the mode you directed of slicing and drying them,” he wrote, “but it did not appear to lengthen their preservation.” The Delaware Indians in Pennsylvania were “very particular in their choice of pumpkins and squashes and in their manner of cooking them,” wrote John Heckewelder, a Moravian who ministered to the tribe in the 1760s and 1770s.

The women say that the less water is put to them, the better dish they make, and that it would be still better if they were stewed without any water, merely in the steam of the sap which they contain. They cover up the pots in which they cook them with large leaves of the pumpkin vine.

Kalm wrote about the Indians’ pumpkin porridge: “Some mix flour with the pumpkins when making porridge. . . . They often make pudding or even pie or a kind of tart out of them.”

Europeans noted the ingenious way Native Americans cultivated their pumpkins and squash, often planting them with corn and beans. Indians called these the three sisters and took advantage of their symbiotic relationship to improve yield. The corn supports the bean vines, the big pumpkin leaves shade the shallow roots of the corn, holding moisture and discouraging weeds, and the bean roots provide nitrogen to the soil. Not all Indians followed this practice, however. Thomas Hariot noted in his Briefe and True Report of the New Found Land of Virginia that the Indian town of Secota had a separate garden “wherin they use to sowe pompions” and another beside it for corn.

Pumpkins are part of a large family of closely related squashes that grow in profusion throughout the Western Hemisphere. The English word “pumpkin” is a modern version of “pompion,” the term broadly applied to many sorts of similar-looking pumpkins and squash. The word’s origins are Greek: pepon means large melon. Though we think of pumpkins as being orange, they also come in green, yellow, red, white, blue, and tan.

The arrival of Columbus in the 1490s kicked off what is now called the Columbian Exchange of food, animals, and disease. Over the years, Europeans introduced cows, horses, pigs, sheep, and many foods to the New World; they took pumpkins, corn, potatoes, sweet potatoes, tomatoes, peppers, squash, pineapples, peanuts, cacao beans, and other items back to Europe and Africa, where they were incorporated into existing foodways.

Kalm was referring to Pennsylvania pumpkins when he wrote, “The Europeans settled in America got the seeds of this plant from the Indians, and at present their gardens are full of it,” but his words would have applied equally to settlers of other colonies. In Massachusetts, the Pilgrims found pumpkin a mainstay. A poem dating from the 1630s tells the important role pumpkin played in their diet:

Stead of pottage and puddings and custards and pies

Our pumpkins and parsnips are common supplies,

We have pumpkins at morning and pumpkins at noon,

If it were not for pumpkins we should be undoon.

Yet Europeans in Europe did not embrace the pumpkin with the same enthusiasm as their brethren in the American colonies. Some upper-class English gardeners grew them as a curiosity, but pumpkins quickly acquired the reputation of being poor men’s fare. The Gardeners Dictionary of 1763 says that pumpkins are “frequently cultivated by the country people in England, who plant them upon their dunghills.” When Martha Bradley wrote The British Housewife in 1770, she termed the pumpkin “a very ordinary Fruit, and is principally the Food of the Poor.” Home in Holland after a visit to New Netherlands before it was renamed New York, a Dutchman reported that the pumpkin was generally despised in Holland “as a mean and unsubstantial article of food, it is there” in New York “of so good a quality that our countrymen hold it in high estimation.”

The most common way to prepare pumpkins was to stew them. A visitor to New England in 1674 wrote:

The Housewives manner is to slice them when ripe, and cut them into dice, and so fill a pot with them of two or three Gallons, and stew them upon a gentle fire a whole day, and as they sink, they fill again with fresh Pompions, not putting any liquor to them; and when it is stew’d enough, it will look like bak’d Apples; this they Dish, putting Butter to it, and a little Vinegar, (with some Spice, as Ginger, &c.) which makes it tart like an Apple.

Another way to prepare pumpkins was to add them to soup or stew. A French cookbook of the mid-seventeenth century describes how to make four types of pumpkin soup using cream, butter, and nutmeg. Other colonial women cut them in half, removed the seeds, put them back together before roasting, and then served them with butter.

Colonial Englishwomen, following the English tradition of making pies out of just about anything, quickly figured out how to make a pumpkin pie, though they didn’t call it that. The first American cookbook, published in 1796 by Amelia Simmons, offers two recipes for pumpkin pudding, one with a “paste,” or crust, and one without. The pumpkin was to be stewed first, then cooked with cream, eggs, sugar, mace, nutmeg, and ginger, and baked threequarters of an hour—a recipe remarkably like the one on the label of the Libby pumpkin can.

Colonial Americans also drank their pumpkin. An enterprising person can make an alcoholic beverage out of almost anything, and the Pilgrims seem to have been first to make pumpkin beer or ale. A later stanza of the poem quoted above provides evidence that they were versatile with their ingredients:

If Barley be wanting to make into Malt, We must be contented and think it no Fault, For we can make liquor to sweeten our Lips Of Pumpkins and Parsnips and Walnut-Tree Chips.

The Pilgrim recipe was said to involve a mixture of persimmons, hops, maple syrup, and, of course, pumpkin. Further south in Virginia, planter Landon Carter mentions pumpkins in his diary in 1765. He, too, concocted some sort of alcoholic beverage from fermented pumpkins. He christened it pumperkin.

Perhaps he used a method similar to an anonymous recipe of 1771:

Let the Pompion be beaten in a Trough and pressed as Apples. The expressed juice is to be boiled in a copper a considerable time and carefully skimmed that there may be no remains of the fibrous part of the pulp. After that intention is answered let the liquid be hopped culled fermented & casked as malt beer.

Pumpkins fed livestock as well as people. Plantation owners like Washington and Thomas Jefferson raised fields of them for winter fodder for their animals. A friend of Jefferson wrote in 1814 about a new, high-yield variety that had been given to Jefferson at Monticello:

The pumkin being a plant of which he endeavors every year to raise so many as to maintain all the stock on his farms from the time they come till frost. . . . besides feeding his workhorses, cattle and sheep on them entirely, they furnish the principal fattening for the pork, slaughtered. A more productive kind will therefore be of value.

Farmers in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries grew pumpkins that were sweet and flavorful, but the fruit’s importance diminished as time passed. Nineteenth-century cookbooks gave short shrift to the pumpkin, some omitting it altogether. Pumpkins became a minor crop until after World War II, when the combination of a baby boom and the end of sugar rationing brought a surge in trickor- treating. The demand for jack-o’-lanterns soared.

It wasn’t until the early 1970s that pumpkins took a turn for the inedible as farmers developed hybrids that were good for carving, not eating. Size, shape, durability, and a thick stem were the desired features. Taste mattered not at all, since none of these pumpkins would be consumed. The Howden Pumpkin strain, developed by farmer Jack Howden, is considered the original commercial jack-o’-lantern pumpkin. It and its offshoots have taken over the market.

“The most popular pumpkins today are grown to be porch décor rather than pie filling,” says history professor James E. McWilliams of Texas State University and the author of Revolution in Eating. “They dominate the industry because of their durability, uniform size (about 15 pounds), orange color, wart-less texture, and oval shape.” Mass production of these poor-tasting pumpkins is a $5 billion a year industry today. McWilliams calls them “a culinary trick without the treat” and accuses them of being “food in name only.”

Edible pumpkins have not been entirely forgotten. Heirloom pumpkin seeds are available for those who want to grow the old-fashioned kind, and farmer’s markets and upscale grocery stores sometimes carry older, tasty varieties.

As pumpkins turned into holiday decorations instead of food, Americans largely forgot how to eat them. Save for the occasional pumpkin pie, the fruit wasn’t seen much on dining tables. But recent years have seen a modest pumpkin revival. The Cheesecake Factory restaurant chain sells two sorts of pumpkin cheesecake during the fall season, Starbucks offers pumpkin muffins and pumpkin scones to hungry coffee drinkers, and magazines feature recipes for pumpkin soups, pumpkin breads, and pumpkin cake.

And that old reliable performer, the pumpkin pie? It’s still bringing down the house after a four hundred-year run.