Once Popular and Socially Acceptable:

Cockfighting

by Ed Crews

photos by Dave Doody

In town and country, for merchant and farmhand, cockfighting—a bloody and usually fatal affair—was close to a national sport in eighteenth-century America, with betting a prime part of it. Colonial Williamsburg interpreters gather round the ring, from left: Tom Hay, Dennis Watson, Bill Rose, James Ingram, Mark Hutter, Dan Moore, Ayinde Martin, Carrie McDougal, and Jay Howlett.

Silver spurs, such as this pair in Colonial Williamsburg’s collections, were fixed as deadly weapons to gamecocks’ legs.

Hankie Dean, one of two Colonial Williamsburg gamecocks, in full fighting profile. Such birds were bred and trained for combat.

In some Colonial American circles, people crowed about cockfighting. As repugnant as pitting two metal-spurred roosters to slash at one another may seem to us, not a few of our ancestors enjoyed the preparations, the crowds of onlookers, the spectacle of combat to the death, and the gambling. “Cockfighting was the second most popular sport after horse racing. Everyone went. People from every class owned gamecocks,” said Elaine Shirley, manager of rare breeds for Colonial Williamsburg’s coach and livestock department.

Because of cockfighting’s popularity in the second half of the eighteenth century, Colonial Williamsburg keeps two of these combative roosters—Hankie Dean and Lucifer—to show guests. The birds differ from other fowl in the Historic Area in that they are big and strong and have athletic builds. They also have been “dubbed,” a practice in which a bird’s wattles and comb were removed so an opponent could not latch onto them in a fight.

Needless to say, Colonial Williamsburg does not fight the birds. That would be inhumane, and illegal. Nevertheless, the gamecocks allow interpreters to discuss a once-popular and socially acceptable pastime, one of a handful of bloody activities enjoyed in the 1700s. In Win or Lose: A Social History of Gambling in America, Stephen Longstreet wrote:

The colonial people bet on wrestling matches, target shooting, and dog and rat fights. Dog fights were a common sport, specially bred and trained pit dogs; dogs against dogs or dogs in a pit against huge rats. The betting was heavy on some champion rat-killer, or on a dog able to stand against another dog to the death.

Cockfighting is as old as the allure of bloodsport. Roman art portrays it—a Pompeian mosaic shows two roosters squaring off. The status and prestige of cockfighting grew in England beginning in the 1500s thanks to royal patronage. Henry VIII was a “cocker.” So was James I.

Cockfighting reached its zenith in British North America between 1750 and 1800. To a degree, its popularity reflected a desire by colonists to ape the behavior of the English upper class. Most enthusiastic were the Americans living from North Carolina to New York.

The men who raised and fought gamecocks bred the most aggressive animals to produce determined fighters in a strain that became distinctive. “During the 1700s, fighting cocks came to look similar in size and shape, although they had different colors,” Shirley said.

Owners gave their birds such names as Thunder and Lighting to suggest combat prowess. They also fed their fighting roosters a special diet, kept them in specific areas, and exercised them to prepare for matches. They strapped finely honed spurs—small pointed blades, sometimes fashioned from silver—to their gamecocks’ legs for weapons.

The combats often were formal affairs. A bout’s sponsor set a place, a date, and a time, and announced the event in the newspaper. Word of mouth also drew crowds, as the marquis de Chastellux noted in 1782 after watching a fight in Louisa County, Virginia:

When the principal promoters of this diversion propose to match their champions, they take care to announce it to the public, and although there are neither posts nor regular conveyances, this important news spreads with such facility that planters come from 30 or 40 miles around, some with cocks, but all with money for betting, which is sometimes very considerable.

An observer of one contest said the cockfight crowd included “many genteel people, conspicuously mingled with the vulgar and debased.” Tavern yards often served as cockfight sites because tavernkeepers made money on fight fans for food and drink, and accommodations.

In Europe well-built cockpits existed before the New World was settled. Londoners could attend fights at such establishments as the Royal Pit at Westminster. This brick and timber structure operated for 110 years and served as the scene for the William Hogarth engraving Pit Ticket. Westminster fights led to the creation of the “Rules and Order of Cocking.”

American fights typically required no fixed location. Combatants—there are records of events in which fifty to sixty pairs of birds fought—met in areas marked by a rope or in an open space between buildings. If there were few permanent cockpits, Williamsburg nevertheless may have had one. Archeological evidence suggests there may have been one at Shields Tavern.

There were other sites. A Virginia Gazette of February 2, 1752 reports: “On Tuesday next will be fought, at the George and Dragon, in Williamsburg, a Match of Cocks, for Ten Pistoles, the first Battle, Five Pistoles the Second, and Two Pistoles and a Half the Third &c. As likewise several other Matches.”

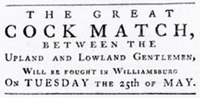

Another Williamsburg match took place in the spring of 1773, announced in the advertisement below:

A notice in a subsequent issue says: “WILLIAMSBURG, MAY 27. On Tuesday and Wednesday last the great COCK MATCH, between the upland and lowland Gentlemen, was fought in this city, when it was determined, by a majority of one battle, in favour of the former.”

Roosters competed with birds of similar weight, much as boxers and wrestlers do today. Combat lasted until one gamecock killed the other, or neither could fight any longer. The finality of death eliminated questions about the victor or the settling of bets.

At a cockfight people visited old friends and made new ones. Some concluded business transactions. Others attended nearby dances after the competition. During the bouts, spectators cheered, drank, ate, and swore. An onlooker wrote that he saw

...some Gentlemen, who, upon other occasions, behav’d with great Decency, and as if they had been influenced with suitable Impressions of the awful and tremendous name of GOD, did then speak and act, as if the Divine Law had been for that Time abrogated, opening their mouths with horrid Oaths and dreadful Imprecations.

The Fights repelled those colonists who found the violence and blood disgusting. Others disliked the wild atmosphere surrounding the competitions. Eighteenth-century traveler Elkannah Watson said he was

...deeply astonished to find men of character and intelligence giving their countenance to an amusement so frivolous and so scandalous, so abhorrent to every feeling of humanity, and so injurious in its moral influences.

Authorities occasionally tried to suppress cockfighting. In 1752, the College of William and Mary directed its students to avoid them. Georgia prohibited them in 1775. The Continental Congress and several states passed legislation condemning the sport. After the Revolutionary War, some citizens of the new United States looked upon cockfighting as an unsavory vestige of English culture and advocated its abandonment.

New attitudes calling for the kind treatment of animals slowly replaced older, harsher ideas. By about 1830, cockfighting generally was considered cruel and wrong. Nevertheless, cockfighting still goes on in the United States as a clandestine and criminal activity.

When Colonial Williamsburg interpreters display Hankie Dean and Lucifer, and describe the colonialists’ love for cockfighting, to guests, reactions reflect the viewpoints about the sport, if sport it was, that took hold in the 1800s.

“People almost always react uniformly when we talk about cockfighting in colonial America.” Shirley said. “They’re horrified.”

They also are puzzled. They have difficulty reconciling the contradiction between what they think of as the eighteenth century’s refinement, decorum, and idealism, and its attraction to spectator activities epitomized by death and wild revelry. Social historian Longstreet wrote of the era: “A general surface of satin laces, polite bows, and high rhetoric hid a desire for blood sport.”

Ed Crews, a Richmond-based writer, wrote the preceding gambling story and contributed to the summer 2008 journal an article on colonial Colonial carriage rides.