Christmas in Prints

by Michael Olmert

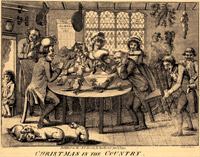

Pranks rather than piety during the holiday festivities are on view in Christmas in the Country, an English print from 1791.

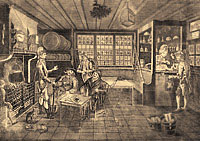

Sprigs of ivy in the windows, mugs of good cheer, and tavern pipes set the season in Settling the Affairs of the Nation.

Seasonally decorative evergreens grace the mantle above a cheery fire and a warming bowl of liquid Christmas cheer.

Holly on the mantel stands a sole, green reminder of the coming new year and a rebirth in the darkling surroundings of December, a calendar print from 1780.

A young woman carries holly sprigs in another December Christmas print that extends the hope of a green renewal against the backdrop of a funereal winter sky.

Try as we might, something seems missing whenever we attempt to take the pulse of Christmas in the eighteenth century. Simply because it’s in the past, I suppose, we expect it to be devout—full of the images we associate with medieval and renaissance Christmases: Madonnas, shepherdy fields, and the baby in an ox’s stall. But novelist L. P. Hartley’s commonplace about the nature of history is perhaps never so true as when we come to consider religion: “The Past is a foreign country; they do things differently there.” In the case of eighteenth-century Christmases, it seems they do things indifferently too.

From the resolutely secular vantage point of today, colonial festivities as recounted in surviving diaries, letters, and newspapers present us with a wan sort of Christmas. So that the “greatest story ever told” looks very much like a time of dressing up, boozing up, and social networking. That is to say, it looks like the same materialistic Christmas people complain about today.

But what did we expect? Most of the seaboard colonies were English after all, and well past the date when Henry VIII outlawed religious art and the remnants of medieval piety. Veneration of the Virgin was out of the question, which pretty much stifled Christmas art or Christmas pageants. Later, the English church adopted a Puritan aesthetic that forbade religious art, statues, and pageantry in its buildings and ceremonies.

If you look in the novels of Jane Austen, writing about society at the close of the eighteenth century, Christmas could scarcely be more secular. It’s mainly gowns, games, and gaiety. In Sense and Sensibility, Christmas is “that festival which requires a more than ordinary share of private balls and large dinners to proclaim its importance.”

Christmas “gaieties,” but nothing reverential, are briefly mentioned in Pride and Prejudice and Mansfield Park. And in Persuasion, Christmas amounts to this:

On one side was a table occupied by some chattering girls, cutting up silk and gold paper; and on the other were tressels and trays, bending under the weight of brawn and cold pies, where riotous boys were holding high revel; the whole completed by a roaring Christmas fire, which seemed determined to be heard, in spite of all the noise of the others.

Another view into the eighteenth-century Christmas is available to us in commercial engravings, mostly printed in London, which were exported to hang on the walls of colonial houses. As with Austen, here, too, the subject matter is almost exclusively secular and rarely spiritual. There may be some moralizing, but it is not specifically Christian, and seldom so much as bows in the direction of the Nativity.

Consider the engraving Christmas in the Country, based on a drawing by Samuel Collings and published by Bentley & Co. in London on January 1, 1791. Aside from its title, the picture signals its Christmas cheer with sprigs of evergreen, stuck onto the glass panes of the casement windows, and the hanging mistletoe, under which the furtive lovers kiss while no one else is looking. The custom of decorating with greenery has pagan roots and is to do with the hoped-for return of life in the spring. Thus the new year triumphs over the old through nature’s vitality. Christianity adapted this green idea to show that it, too, offers the hope of victory over death, a green and pleasant eternity. Hence the custom of planting evergreens, especially yew, in church cemeteries.

Christian symbolism seems lost on these revelers. An inebriate removes a hat and replaces it with a tipsy chamber pot, which he balances on the head of a man blowing smoke in the face of his neighbor, who squints and strokes his ample and groaning girth. Two blowsy ladies look on, as one of them knocks the wig off a man fishing for something in the Chinese export porcelain punch bowl—possibly his spectacles? Meanwhile, he is about to sit on a chair being pulled out from under him by a lad who, in turn, is having a tankard of punch poured into his pocket.

We can see that the New Year is at hand because the 1791 almanac is replacing the 1790 broadside on the wall. It’s a carpe-diem moment. Time will catch up with these people, even the lovers. Especially the lovers. Overhead, the gaming and drinking culture of the tavern is clear from the billiard sticks and the prominent beer pitcher on the mantel. The hounds, those watchdogs of faith and morals, have gone to sleep. And the cat has never seen such sight.

Samuel Collings painted the picture on which the engraving was based. He died about 1793 and was influenced by William Hogarth. The centerpiece here is the porcelain punch bowl, around which the action swirls, just as it does in Hogarth’s 1733 engraving Midnight Modern Conversation. The arc of fluids, from punch bowl to chamber pot, is here as well. Like Hogarth, Collings focuses not merely on drunkenness but on the absence of morality. Satire can never be polite.

A similar tavern scene is Settling the Affairs of the Nation, an engraving published by the London print sellers Bowles & Carver about 1775. Two hundred years later, Joni Mitchell would sing it was “coming on Christmas, and they’re cutting down trees.” But Bowles & Carver’s clientele knew it was the season because little cuttings of evergreen appear in the windowpanes. Four small wreaths decorate the front door. And mistletoe dangles, unheeded, from the ceiling while a grenadier and four tipsy customers dilate on politics and sort out “what England must do.”

That is, the Christmas greens carry the message of eternal renewal and the satirical bite comes from the print’s disparity: the heat and dust of ephemeral news versus the eternal calm of Christmas. It’s likely that some buyers of the print understood that whatever was being discussed that day would soon fade, but Christmas would stay news.

Meanwhile, a dog dozes away his responsibility. Like a fire dog, he is expected to bark his master into moral wakefulness. But he does no such thing.

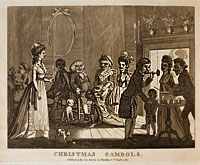

A large engraving that folds out is the usual frontispiece in every issue of The Wit’s Magazine, published in London in the mid-1780s. For the December 1784 number, the engraving is titled Christmas Gambols, based on a painting by the caricaturist George Murgatroyd Woodward. For good measure, the opening article is a short narrative by Woodward, unpacking the complex goings-on in his picture.

For starters, apart from the engraving’s title, we know this is Christmastide only from the evergreen cuttings in three loving cups on the chimneypiece. The scene is set, Woodward tells us, in the home of a wealthy citizen who is hosting a holiday party. Fortunately, Woodward confides, this man “has happily not attained to so much modern refinement as to despise those innocent gambols which amused his forefathers.” That is, urban sophistication and prideful Puritanism have not stopped him from enjoying such ancient parlor games as Blind Man’s Bluff, Hunt the Slipper, or Forfeits, the three games on offer that night. In each of them, a kiss is typically the winner’s reward or the loser’s punishment.

Into his picture and story, Woodward gathers stock characters: the parson with the “ecclesiastical failing of preferring women to the liturgy,” the host with a nose “finely tinted with vermilion,” the eager bumpkin Ralph Jones, unacquainted with modish London ways, and pretty maids. Woodward sits on the floor and deals out forfeits from the lap of a woman called the treasurer, who keeps the rewards and punishments on little papers under her apron. While the bumpkin is being humiliated by having to kiss a cold candlestick, in a dark corner the parson seizes that moment to kiss the old maid, “who seems as quiet in her situation as if she had been in her Sunday’s pew.”

The clergyman plays the game so well he gets the lion’s share of kisses, which infuriates Jones. Rounding on the parson, he demands to know if “his reverence had a license from the bishop to kiss his neighbours wives and daughters.” At which point the laughter is so merry it carries off the tension. “In short,” Woodward says, “we spent the remainder of the evening with the utmost conviviality (for my friend never suffers a pack of cards to enter his house) and I returned home about five in the morning.” The family dog, Jowler, takes it all in, but this is no Silent Night. Meanwhile, the mistletoe on the mantle offers charity, but all it sees is cupidity. Which is instructive.

A vase of holly on the mantle is the main source of Christmas cheer in the print named December, part of a series on the twelve months of the year published by Carrington Bowles in 1780. In it, an elegant dame representing the year sits alone at a table and is about to tug at the bellpull, signifying that her day is at an end, and she can be put to bed. She’s wrapped up against the cold and stares wistfully into the hearth, which sheds its last measure of light and heat. Her cat backs up into the soft heat as well. A heavy curtain against the cold window has been pulled back to reveal a declining moon. The lady holds a candlesnuffer in her left hand. It can’t be long now. Although the picture is mainly secular, its invention is carpe diem, a classical idea entirely suited to Christianity. Every life, as every year, must at long last come to an end. Only the greenery holds out a ray of hope. Holly is still vital, even in December. Its bright berries represent the blood of Christ, and promise new life and everlasting prosperity, the crucial Christmas message.

Another December is printed last in a series of engravings on the months published by Robert Sayer in London in 1767. Rather than passively waiting for the end, however, this Decembrist lady is bundled up against the cold and is outside collecting Christmas greens in the gathering twilight of the year. Possibly these plants can hold off the dying of the light, she suggests. And so she holds up a holly sprig in one hand and carries another bunch in her apron.

An urn behind her is full of berry-laden greenery that seems to be mistletoe. Has she just come from arranging cuttings in the urn? Certainly the tilt of her body suggests movement away from that urn and toward the next. Is she on her way to arrange the holly in another pot in this topiary garden under the darkling sky?

This is a sublime landscape, urged on by the late eighteenth-century urns that had become symbols of death in art and sculpture, as well as on churches and headstones. An urn was the ultimate memento mori. The idea came from the Roman custom of burying the ashes of the dead in stone urns, which were turning up in archaeological sites and farmers’ fields all over Britain. The surprise and delight of this print is a witty December who gives us the comfort of mistletoe instead of cold, lifeless ash.

What we see in these images, and in late eighteenth-century Anglo American culture, is the transference of religious ideas and ritual into the secular world. Still, the old ethical and moral concepts and tales hang on as metaphor and analogue, even when they are no longer overtly expressed. They saturate everything and quietly resonate. The religious insight that life is a pilgrimage and that we need be good to earn personal eternity, to triumph over death, is addictive. Which is to say, once you’re dead, you’re dead for a very long time. Christmas, it was once widely thought, could help with all that.

Michael Olmert, teaches English at the University of Maryland. For past holiday issues, he has written about the long Christmas season, Christmas games, Christmas plays, and The Skating Minister.