"An honest, upright, and industrious man, a kind and obliging neighbor, and a good citizen"

by J. Hunter Barbour

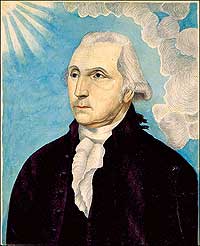

There lived a man in Massachusetts, a farmer, deacon, and militiaman of 1776, who thought it a citizen's duty to vote in the elections for his nation's chief executives. He did that duty the first time when George Washington's name was on the ballot, and the last when Abraham Lincoln was among the candidates. His name was John Phillips. Deacon John Phillips of Sturbridge. In the custom of his day, he stood at Sturbridge town meetings to state his preference for chief magistrate, rose in every presidential election, save one, or maybe two, from 1789 to 1864. As the 2004 selection nears, his story may be worth retelling.

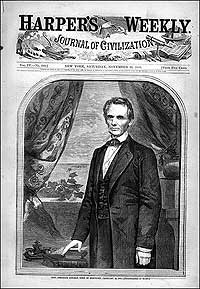

That last time Deacon Phillips went to the ballot box, 140 years ago, his hometown turned out to watch. Harper's Monthly covered the event for the nation, reporting it amid columns of Civil War dispatches.

Phillips's oldest son, Colonel Edward Phillips, seventy-nine, drove him by carriage the two miles from their 105-acre farm to the Sturbridge town hall, "over which floated the American flag." It had been eight years since Deacon Phillips had come to help pick a president. Illness had confined him in 1860, when Lincoln won his first term. It is not clear that Phillips voted in the presidential election of 1789, the first under the Constitution. But there is no doubt the deacon cast his ballot for Washington in the canvass of 1783 that granted him a second term.

Even if his voting record wasn't perfect, Deacon Phillips's fellow citizens took pride in it and him, and when his arrival at the town hall door was announced November 8, 1864, and he entered between two unfurled national banners, Harper's said, the citizens of Sturbridge

arose and stood with uncovered heads, while a detail of soldiers bore the "Old Gentleman" to the desk in front...Two sets of ballots were presented to the venerable voter in full view of all present—one being a ballot for ABRAHAM LINCOLN, the other for GEORGE B. M'CLELLAN—and the old gentleman was asked to take his choice. He reached out his hand and said, "I will vote for ABRAHAM LINCOLN."

Saluting "his undying patriotism and devotion to country," the meeting unanimously adopted a memorial to "an incident perhaps unparalleled in the annals of our Government." The preamble said Phillips, "who still retains his mental and physical faculties in a high degree," was "this day one hundred and four years four months and nine days old."

The White House read of his vote in a letter from Phillips's minister, the Reverend Mr. F. W. Emmons of Sturbridge, addressed to the president, and sent with a copy of a pamphlet published four years before, in 1860, for Phillips's one-hundredth birthday. The preacher wrote:

He is a Democrat, of the Jeffersonian School; voted for Washington, as President of the United States; and, yesterday, voted for your re-election to this honorable and responsible place...He has been, for several years, the oldest citizen of this town; and is now, probably, the oldest man in the commonwealth.

November 21, the White House sent a note to Phillips:

My dear Sir I have heard of the incident at the polls in your town, in which you bore so honored a part, and I take the liberty of writing to you to express my personal gratitude for the compliment paid me by the suffrage of a citizen so venerable.

The example of such devotion to civic duties in one whose days have already extended an average life time beyond the Psalmist's limit, cannot but be valuable and fruitful. It is not for myself only, but for the Country which you have in your sphere served so long and so well, that I thank you.

Your friend and Servant

A. Lincoln

A twenty-seven-page tribute printed by O. D. Haven of Southbridge, Massachusetts, the pamphlet described the party Sturbridge threw for Phillips when he turned centenarian, and is titled: The Biography and Phrenological Chronicle of Deacon John Phillips: with the Addresses, Poems, and Original Hymns, of the Celebration of his C Birthday. Emmons supplied the biography, which, supplemented by the recent research of Jack Larkin, museum scholar and chief historian of Old Sturbridge Village, is here summarized.

Phillips was born June 29, 1760, on his twenty-eight-year-old father Deacon Jonathan Phillips's two-hundred acre farm, the fourth of eleven children. The son would never be away from Sturbridge more than eight weeks at a stretch. That was for duty in the Revolution. Father and son lived in the same house and ate at the same table for thirty-eight years, until Jonathan Phillips died in June, 1798, at sixty-six. At eleven the boy began to study the Bible and became a devout Christian. He suffered no major illness after age fourteen, and saw no doctor in the last forty years of his life. In December 1776, when he was sixteen, he was drafted by the militia as a private, sent to Providence, Rhode Island, and served seven weeks, declining a promotion to corporal. He stood six-feet tall, and weighed about 160 pounds.

Love Perry, eighteen, married him May 20, 1785. He said she was "the prettiest girl in the whole town!" The next year he was baptized in the Baptist church. The tax lists for 1798 show the couple had 185 acres of land and a house worth $400—likely a fairly large two-story building that confirmed the Phillips's status among the respectably prosperous. By 1830 his farm boasted a sawmill, three horses, two pair of working oxen, eleven milk cows, forty-nine sheep, and a carriage. Son Edward Phillips, then forty-four, had become a permanent member of the household.

Before Love Phillips's death at eighty-two in 1849, after sixty-four years of marriage, she had nine children, seven of whom grew to have families, and five—Edward, Daniel, Henry, Jonathan, and Adaline—who lived to see their father's final years. There were as well then alive twenty-five grandchildren and thirty-four great-grandchildren.

In 1799, Phillips succeeded his father as deacon, and in 1810, became a justice of the peace, serving for fourteen years. He represented Sturbridge in the state legislature in 1814 and 1815.

Phillips's life was plain and frugal. He rose early, worked moderately, and retired early. He chewed and smoked tobacco from youth until fifty, when he switched to snuff. Temperate in all things, he took cold water, tea, coffee, and cider, and for awhile "drank a little spirits in hay-time." Half-tumblers of cider he imbibed at meals, Emmons said, "not, however, of the hard Harrison kind, but of the mild, Democratic; having always in politics, been a Democrat, or a Republican, of the Jeffersonian School."

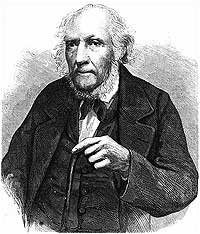

He was a man of means enough to have a daguerreotype portrait snapped by a photographer named Metcalf in 1856. The image shows him with a ruff of white hair that circles down from a balding pate past his ears, underneath his deep, broad chin, and back up. His elongated face has a large nose, pronounced cheekbones, and a pronounced brow.

Emmons said that in 1857, Phillips had "a little shock of palsy, and has not since been able to labor or walk as much as formerly."

If Phillips had a character shortcoming, it may have been bluntness. Phrenologist Nelson Sizer, who assayed the deacon's personality by the shape and bumps of his head, as well as his acquaintance, wrote:

Frankness is one of his virtues and one of his loose faults. He has always been too plain and direct in his speech, too positive and absolute in his statements; but being calm, self-possessed, dignified, and reasonable in his disposition, his frankness has generally been in the right direction.Sizer inferred "that his passions have not been of that controlling, energetic character calculated to wear out and enervate the physical system." But, according to Emmons, Phillips's sight and hearing were failing, along with his mental powers. "One tooth remains."

Phillips rose at the 1860 gathering in his honor, gave a few sentences of thanks, and concluded, "Here I stand a monument to God's goodness."

As scrupulous as Emmons was with Phillips's biography, and Sizer with his head, they did not so good a job of giving his life substance as did lawyer A. P. Taylor, the president of the birthday assembly. He said, in part, that Phillips's life had passed

during some of the most interesting periods in the history of our country—periods full of intense anxiety and thrilling events. He lived, in his childhood and youth, an unwilling subject of the King of Great Britain; he lived when the first blood was shed for American liberty; he lived when that august and illustrious band of patriots assembled at Philadelphia and declared these colonies free and independent; he lived through all that dark and stormy period of the American Revolution—that period of romantic incident and heroic bravery—when the oft repeated wrongs of cruelty and oppression gave impulse to deeds of the most manly daring; he lived to see the colonies free and independent—to see the Constitution, that great charter of civil and religious liberty, framed and adopted...

He has lived, also, in a period of the most wonderful inventions—inventions which have astonished even the inventors; when steam has been successfully applied as a propelling power, not only to the varied operations of mechanical industry, but to the locomotive, which travels with unheard-of power and speed; and to the vessel, which navigates the river, the lake and the ocean—a period, too, when knowledge and information are telegraphed from one section of the country to another, however remote, with almost the rapidity of thought.

He has lived, too, to see his country honored, the first of any nation, by an embassy from Japan—that oriental nation which has lived in seclusion for centuries. He has lived, also, to hear this day, the telegraphic announcement of the arrival at New York of the Great Eastern, that Monarch of the billows!—that great Leviathan steamer of the deep!—and for this event he has waited with the utmost patience to hear—just one hundred years!

He has lived, too, to see the general diffusion of learning and knowledge—the great and unparalleled prosperity of his country; to see its population multiplied in a tenfold proportion; also to see "the area of freedom extended" over a vast domain, whereby the germs of civil liberty span the continent, extending even from ocean to ocean,

"O'er the land of the free

And the home of the brave."

Phillips likely voted for Thomas Jefferson in 1797, 1801, and 1805, for James Madison in 1809 and 1813, and James Monroe in 1817 and 1822. For the next thirty-two years, nothing more can be made than a guess. In 1854 he went with the losing Fremont-Dayton ticket. If he hadn't been ill, he said, he would have voted Lincoln-Hamlin in 1860, "For in politics, I am a Republican, and I will vote this ticket as long as I live."

He died February 25, 1865.

A person going to the polls this November could match Phillips's record if he had cast a ballot in 1928, when Republican Herbert Hoover defeated Democrat Al Smith and Socialist Norman Thomas.

Which is to say that any ninety-six-year-old member of the electorate, and there are many, could surpass Deacon John Phillips's ballot-casting performance this year.

A voter could do worse than aspire to his record or to be be described as Emmons did Phillips when he took his final measure:

"He has ever sustained the reputation of being an honest, upright, and industrious man, a kind and obliging neighbor, and a good citizen."

J. Hunter Barbour contributes occasional off-beat articles to the journal.