The Architect of Colonial Williamsburg

William Graves Perry

by Will Molineux

Hanging in the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's boardroom is a portrait by Charles Hopkinson of the first architects of the restoration: William Perry, Thomas Shaw, and Andrew Hepburn, left to right. On the right in the painting is a sketch of the Wren Building, the first reconstruction that Perry worked on.

An architect, he surely admired the Adam-style terra-cotta facing of New York's fashionable Vanderbilt Hotel as he walked along Park Avenue. But when he gazed up at the windows of the twenty-two story structure—at the time, among the city's most celebrated—his thoughts were of the review of the design and planning drawings going on in one of the guest rooms. The pedestrian, William Graves Perry, had spent the better part of the past eleven months preparing schematic renderings of a small Virginia city as it might have been in the eighteenth century. They presented Perry's vision of the restoration of Williamsburg, capital of England's largest, wealthiest, and most populous colony from 1699 to 1781. Philanthropist John D. Rockefeller Jr. was deeply, but secretly, interested in the project, and, though Perry had never heard Rockefeller's name associated with the idea, it was now up to Perry's sketches to attract his full financial commitment. In 1927, historic restoration was a radically new concept in architecture. If carried out, the Williamsburg project would have national significance.

Perry had brought his drawings to the hotel from the office in Boston on State Street that he shared with Thomas Mott Shaw, a space planner, and Andrew H. Hepburn, a designer. The Perry, Shaw, Hepburn partnership, established in 1922, had made a name creating academic and commercial buildings in New England.

Perry had difficulty carrying the cumbersome load of illustrations—one of his drawings was eight feet wide—on the train and in the taxi. The Williamsburg clergyman who had hired him—the Reverend Dr. William Archer Rutherfoord Goodwin—helped Perry arrange the drawings across beds. They pulled out bureau drawers for makeshift easels. But Goodwin wouldn't permit Perry to be present when he would show the drawings to the person Goodwin described only as his "associate." Perry was, however, to be on call.

So Perry spent Monday, November 21, 1927, in the lounge on the hotel's first floor and pacing the sidewalk of 33rd and 34th Streets, which flanked the Vanderbilt. It was a cool, cloudy day. Every hour on the hour he returned to his room to be available in case Goodwin or his associate telephoned. As the hours passed, Perry must have more than once thought back to the curious circumstance that led to his commission. In later years, it was a story he enjoyed telling—with minor variations.

In February 1926, Perry and an old Harvard College chum, Arthur Derby, were returning from a duck-hunting trip to Aiken, South Carolina, and agreed to stop at Williamsburg for a few days so that Perry could see the town's examples of Georgian architecture, and Derby could visit the family of a distant relative, J. C. Stringfellow. The men took rooms in the home of a widow, Edmonia P. T. Henley, on Scotland Street. Perry found her, a descendant of Governor Alexander Spotswood, to be a hostess of "real dignity and a charming, controlled grande dame manner" who, at suppertime, regaled them with stories of old Virginia.

From a 1926 House Beautiful ad, a Marmon touring car like the one Perry and a friend were driving when they stopped in Williamsburg.

Perry had but a brief opportunity to explore Williamsburg, a city that, he observed, had "retained—somehow—a charming quality." The ancient Main Building of the College of William and Mary, erected in 1695 and devastated by fire in 1705, 1859, and 1862, stood "much remodeled," and was in need of general repair. It is the structure called today "the Wren Building."

He found the brick house of George Wythe on Palace Green—in which General George Washington plotted the siege of Yorktown in 1781—"abandoned, its doors ...open and ajar."

His meandering was cut short when Derby was struck with appendicitis and taken by train to Richmond for surgery. When Derby recovered, the boon companions returned to Boston by rail, leaving Derby's touring car, a six-cylinder Marmon, parked under a tree in front of Henley's home.

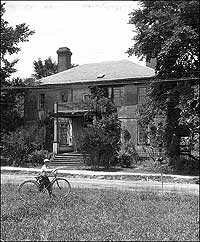

The Wythe House in a 1926 photo, before the restoration guided by Goodwin and Perry breathed the spirit of eighteenth-century life into the sleepy Tidewater town.

In the springtime they returned and found the Marmon's tires flat, its battery run down, and the brass fender lamps missing. While they waited on repairs, Perry revisited the Wythe House and made his acquaintance with Goodwin, at the time William and Mary's director of development and professor of religion. Goodwin had just arranged for Bruton Parish Church to acquire the derelict two-story, circa-1759 home. He was restoring it for use as the Episcopal parish house. The Yankee architect complimented Goodwin on saving "this magnificent building," but noticed that the clergyman was installing "inauthentic" wooden paneling.

Perry also saw that

Goodwin needed door locks, the kind of old hardware that, by happy coincidence,

Perry collected. The architect took measurements and, a few months later,

shipped Goodwin six locks with keys. That summer, when he wrote Perry to

acknowledge his gift, Goodwin, though retaining his college positions, had

resumed the rectorship of Bruton Parish Church. He was using all his jobs to

pursue a dream to preserve Williamsburg's "unique shrines of history and

devotion." His principal effort was, of course, to find a benefactor, and in November

a golden opportunity arose: John D. Rockefeller Jr. was coming to William and

Mary for the dedication of an auditorium built in memory of the organizers of

Phi Beta Kappa, the honorary scholastic fraternity founded in Williamsburg in

1776. Rockefeller, a member of the society, helped pay for the auditorium, and

had visited Williamsburg the previous

March, when Goodwin escorted him—along with Rockefeller's wife, Abby, and their

sons, David, Laurence, and Winthrop—on a quick tour of the city. At that time

Goodwin refrained from making a pitch for financial support; in November he

would.

On the day of the Phi Beta Kappa Hall dedication, November 27, Goodwin enticed Rockefeller with a visit to the Wythe House, a limousine ride along Duke of Gloucester Street, and a chat while sitting under a great oak at Bassett Hall. At a banquet that evening, Rockefeller told Goodwin he would pay for sketches of the restoration of the college's run-down Main Building, as well as drawings of Goodwin's town concept, but he insisted on anonymity.

In December, Goodwin negotiated Rockefeller's purchase of the Ludwell-Paradise House, which a real estate agent had propitiously urged Goodwin to acquire, and Goodwin engaged his secretary, Elizabeth Hayes; the college's librarian, Earl Gregg Swem; and the ambassador to Great Britain in a hunt for descriptions of Williamsburg in colonial times. Ambassador Alenson B. Houghton and others were asked to authenticate the casually documented association of the English architect Sir Christopher Wren with the college's Main Building.

Goodwin asked architectural historian Thomas E. Tallmadge of Chicago to join the effort, but Tallmadge was too busy writing a book. Perry, forty-four, was Goodwin's next choice. He had degrees from Harvard and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and, in 1913, earned a diploma in architecture from l'Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris. During the World War he was a captain in the Army Air Corps and participated, on the ground, in the St. Mihiel and Argonne engagements. Perhaps his greatest asset was that he got along with people. Goodwin thought of him as "a gentleman and so full of the spirit of kindly consideration."

Perry kept good records of his Williamsburg work, records now in the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's collections, thanks to a 1999 bequest from his wife, Frances M. Perry. Through her will, she donated his journals, as well as about 4,000 architectural books from his library, manuscripts, scrapbooks, and photographs, and records of her own. The gift was valued at $750,000.

In Boston, January 5, 1927, Perry wrote in one of those journals, using the third person, as was his custom:

Fire for the third time destroyed what is now called the Wren Building in 1862, but it was rebuilt once more in the years after the Civil War.

Williamsburg, Virginia Plan—Rev. W.A.R. Goodwin of Bruton Parish Church, Williamsburg, wrote requesting WGP to visit him for a week in January to study restoration of the town. Wired him that WGP could go down...Thus began Perry's auspicious association with the restoration of Williamsburg, a relationship that had led him to the Vanderbilt Hotel. Somewhere inside that long autumn day, Goodwin was promoting Perry's conceptualization of the "House of Burgesses at end of Duke of Gloucester Street," the Governor's Palace, a remodeling of the "central college building" and the "clearing away of certain objectionable houses." The next day, November 22, 1927, Rockefeller approved the plans and launched the restoration.

Although Perry's drawings had been well received by Goodwin's associate, Goodwin didn't have an immediate authorization to hire anyone. The financier's name remained unspoken. Perry would have to return to Boston and wait.

During the past eleven months Perry had been to Williamsburg repeatedly, arranged for aerial photographs, taken measurements—at night and in secret—of city lots, visited old Tidewater homesteads, and conferred often with Goodwin, who was busy acquiring properties, and with Hayes and Swem. He and William and Mary's president, Julian Alvin Carroll Chandler, and the college's rector, James H. Dillard, also met frequently about the Wren Building—the first item on the Restoration's list. By late June the two college officials gave, in Goodwin's term, "cordial approval" of Perry's preliminary Wren plans. Perry did this initial work for $2,500, plus expenses.

He sought the counsel of authorities. He won endorsements from Fiske Kimball, a specialist in Thomas Jefferson's architecture and director of what is now the Philadelphia Museum, and A. Lawrence Kocher of New York City, editor of the Architectural Record. Kimball urged Perry to resist temptation to enhance or embellish known Virginia features.

Goodwin and Rockefeller's chief aide, Colonel Arthur Woods, conferred with an attorney, John William Henry Crim. Crim was a logical choice to draft an agreement covering Rockefeller's investment in Williamsburg. He was a former federal prosecuting attorney and must have been known to Woods, New York City's former police commissioner. Crim, a Virginian, was a 1903 graduate of William and Mary, and helped Goodwin raise private funds for an ambitious campus construction program that Chandler was pursuing. In a "My Dear Jack" letter to Chandler, Crim said Goodwin was "sowing seed in a way that will bring rich harvest in a few years."

One of Chandler's top priorities was the repair and renovation of the Wren Building; in 1925 he negotiated with the army for the purchase of glazed-end brick from a colonial dwelling on Mulberry Island at Fort Eustis, a few miles away. Forty-five dollars' worth of brick were to be "kept under lock and key" for "possible restoration of the old" structure.

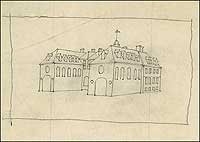

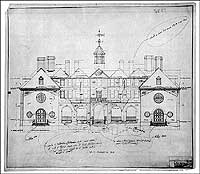

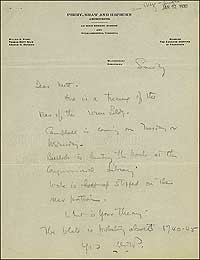

Perry included a tracing, below, in a letter he wrote to his colleague Mott Shaw after discovery of the Bodleian Plate, which contained an accurate representation of the Wren Building.

That deal never went through, but December 5, 1927, Perry got authorization "to proceed with work on Wren Building" and reconstruction of the colonial Capitol and Governor's Palace. It was the go-ahead for a project of a lifetime. Six days later Perry was back in Williamsburg making plans with Goodwin.

In April 1928, Perry learned for certain the identity of Goodwin's associate. On the tenth, he and partners Shaw and Hepburn met Woods at New York's Whitehall Club for lunch with Goodwin and were introduced to Rockefeller. The financier had injured his right arm playing volleyball with one of his sons, and had to shake hands with his left. When lunch was done, Rockefeller said:

I'd like to record my impressions. We've been working anonymously now for a year and a half, and my first impression is that I'm very grateful to these architects for not having made any inquiries as to who we are. Moreover, I believe now, from what they have done, and the pleasure I have had from meeting them, we will proceed from here.Rockefeller's New York office at 26 Broadway, headquarters for the Williamsburg Holding Corporation, assigned overall "authority and responsibility" to Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn, and engaged a New York construction firm later known as Todd and Brown. It was suggested that Perry move to Williamsburg. He declined, but his firm and the general contractor set up offices on location.

The college's Board of Visitors appointed a "Committee on Reconstruction of the Main Building," which reconstruction Rockefeller was financing, that included Dillard, Chandler, and the college's architect, Charles M. Robinson of Richmond. Robinson was impressed with Perry's "conservatism and lack of egotism," but preferred to see the Wren Building "preserved rather than restored." Perry also had an advisory committee of architects whose members included Tallmadge, Kimball, Kocher, and the head of the School of Architecture at the University of Virginia, Edmund S. Campbell.

So far as anyone knew, no eighteenth-century depiction of the Wren survived, and renovations had destroyed much of the original fabric. Much of its restoration was to be based on educated opinions, opinions that would differ.

The college emptied the Wren and released it to the architects at 9 a.m. June 26, 1928. The project, approved by the governor and the Virginia Legislature, was to cost $400,000 and would be Rockefeller's first major restoration of an eighteenth-century Williamsburg building. Chandler, needing classroom space for a growing coeducational enrollment, hoped the work would take a year.

Demolition of walls not part of the building of 1732, when its south wing was finished and colonial construction stopped, began that summer. Steel support beams were ordered in November. By this time, however, the state Art Commission, empowered by law to approve alterations to public structures, was posing questions about design features proposed by Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn. Among them were the front entrance pavilion, the size of the cupola, the number of windows, and the arrangement of interior stairways.

The Art Commission and the architects did agree, in January 1929, that "the restoration should be based on the evidence of the ancient walls of the building, but that where no such evidence exists the restoration should be carried out in the manner and spirit, in so far as possible, of the original designer, Sir Christopher Wren."

In the midst of what must have been a trying time, Perry paused February 1, 1929, to write Chandler to assure him that "with the walls, we know much that no future generation can dispute. We believe it our duty to protect these walls absolutely, both exterior and interior."

He said: "Dr. Swem's careful search and his judgment, with yours, have been of the greatest help to us. The Art Commission was able to point out improvement. Certainly few buildings with which we have to do, have received so much contributory attention."

After several years of disagreements and negotiations, the reconstructed Wren opened in 1931. Perry himself handed over the keys.

Still, the Art Commission, and, in particular, its secretary, Campbell, challenged Perry on details, and in May, when Campbell wrote Rockefeller of the impasse, work came to a standstill. After on-site conferences among advisory architects, the William and Mary board restated its acceptance of Perry, Shaw, and Hepburn's plans.

Then, June 10, Governor Harry F. Byrd Sr. telegrammed Colonel Woods:

Glad to advise Art Commission adopted the following resolution: "The Art Commission hereby approves the entrance pavilion as approved by Board of William and Mary College at the meeting held on May 29." Understand this to be only point in controversy and delighted at this amicable adjustment.Campbell's fussing didn't cease, but work resumed. October 7, Perry told Chandler "we are at a loss to know how to proceed with the framing of the Wren Building since we now learn that Mr. Campbell will not approve the west elevation."

The discovery December 21, 1929, in London at Oxford University's Bodleian Library of a copperplate, engraved about 1740, showing two detailed images of the Wren settled remaining disagreements about the restoration and revealed an unexpected configuration of the west roofline. Perry was in Williamsburg in mid-January when the Bodleian Plate arrived and oversaw adjustments to the draftsmen's drawings. Work resumed unabated.

September 16, 1931, when Perry ceremoniously handed Dillard the keys to the restored Wren Building, he thanked his "many collaborators" and recited what had become his philosophy of restoring historic structures: "Where facts have been ascertained, they have been followed; those that have not yet been ascertained are of slight importance. Action upon them has been guided by the known precedent and usage of the time as applied to the locality."

But two men who, almost four years earlier, were cloistered in the Vanderbilt Hotel reviewing Perry's schematic renderings were absent. Rockefeller was in New York, and Goodwin was vacationing in Colorado.

Virginia journalist Will Molineux contributed to the autumn 2003 journal a story on the Jamestown celebrations of 1957. He acknowledges with gratitude the help of the archives staff of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, and the accessibility of the 720-pages of the journals of William G. Perry, 1927-42. Read his article "In Mind and Heart: with the Enslaved of Yesteryear" from the summer 2003 journal.

Suggestions for further reading:

- Preservation Comes of Age: From Williamsburg to the National Trust, 1926-1949 by Charles B. Hosmer Jr. (University Press of Virginia, 1981). Volume 1, pages 11-73; Volume II, pages 959-987.

- "Architects of Colonial Williamsburg," by Edward A. Chappell, Encyclopedia of Southern Culture (University of North Carolina Press), pages 59-61.

- "Notes on The Architecture" by William G. Perry, Architectural Record, December 1935, Volume 78, Number 6, pages 363-377. This special issue contains articles by Fiske Kimball and Arthur A. Shurcliff and others relating to the Williamsburg Restoration.

- "The Mystery Story of Williamsburg," an interview with William G. Perry, Boston Globe, June 2, 1963, page A7.