Rediscovering an American Icon

Houdon's Washington

by Tracy L. Kamerer and Scott W. Nolley

In the rotunda of the Capitol in Richmond, Jean-Antoine Houdon’s Washington has stood for more than 200 years. The portrait in marble unfolds the layers of Washington’s life: general, statesman, farmer, citizen. It may be his most exact likeness.

In Richmond stands a marble statue of George Washington that is among the most notable pieces of eighteenth-century art, one of the most important works in the nation, and, some think, the truest likeness of perhaps the first American to become himself an icon. A life-sized representation sculpted by France’s Jean-Antoine Houdon between 1785 and 1791 on a commission from Virginia’s legislature, it was raised in the capitol rotunda in 1796, the year Washington published his Farewell Address. The commonwealth’s records detail its creation and its initial reception by the public, but the object has been the subject of little scholarly or scientific attention. The work’s existence after it left Houdon’s studio and arrived in America has been largely undocumented, and the statue’s relationships to its artistic and historical contexts have not been examined. In 2000, the year the Virginia General Assembly and the Library of Virginia approached Colonial Williamsburg Foundation conservators to clean the statue, came an opportunity for study.

This is an account of the collaboration between the two of us—Scott Nolley, the project’s chief conservator, and Tracy Kamerer, the state art collection’s curator—which developed more information about this emblem of American culture.In 1784, after Washington left the army’s service to return to private pursuits, the Virginia legislature resolved to honor him with “a monument of affection and gratitude” by ordering a statue of the man, “to be of the finest marble and best workmanship.” It was apparent that there were no American sculptors up to the task, so Governor Benjamin Harrison asked America’s ambassadors in Paris, Thomas Jefferson and Benjamin Franklin, to select one. The governor also wrote to Charles Willson Peale of Philadelphia to order a full-length painting to serve as the sculptor’s model.

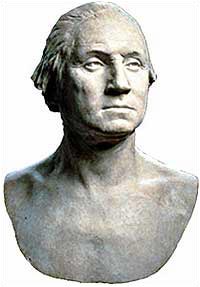

By December, Jefferson wrote to Washington that he preferred the world’s premier sculptor, Houdon, then engaged by the Russian Empress Catherine. Jefferson noted the artist’s eagerness to have the commission, but said Houdon believed a portrait would not suffice for the likeness required for such an important undertaking. Houdon insisted upon coming to America to study Washington himself. He left France in July 1785 and arrived October 2 at Mount Vernon for a two-week stay. During the visit, he modeled a terra-cotta bust of Washington, made a life mask, and took measurements of his body. Washington was apparently intrigued by the artist’s activities and recorded them in his diary. On October 17, 1785, Houdon left the plantation with a plaster mold of the bust, the mask, and notes. The original terra-cotta bust remains at Mount Vernon, and the mask is at the Pierpont Morgan Library in New York.

Houdon, back in Europe and poised to begin his work, addressed the question of how to clothe the statue. Jefferson wrote to Washington for his opinion in January 1786, and Washington said in August:

I do not desire to dictate in the matter. On the contrary, I shall be perfectly satisfied with whatever be judged decent and proper. I should even scarcely have ventured to suggest, that perhaps a servile adherence to the garb of antiquity might not be altogether so expedient, as some little deviation in favor of modern costume, if I had not learnt . . . that this was a circumstance hinted in conversation by Mr. West to Mr. Houdon. This taste, which was introduced in painting by West, I understand is received with applause, and prevails extensively.

Washington refers to American expatriate Benjamin West, who caused a sensation with his painting The Death of General Wolfe in 1770. It portrayed the heroic death of a British general mortally wounded leading his troops in battle against the French at Quebec in 1759. The uproar was because West had painted a recent episode using the accepted format of history painting, but he had clothed his general and soldiers in contemporary military uniforms—not in the accepted garb of antiquity. Despite the controversy, The Death of General Wolfe set an example for history paintings and sculptures that followed. It is probable that Houdon consulted with West while working on the statue.

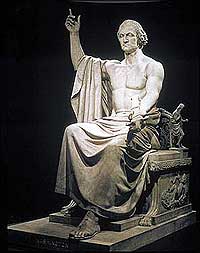

The decision to dress Washington in his Revolutionary War uniform

was wise. Consider public reaction to similar commissions: Antonio

Canova’s 1816 monumental Washington statue for the North Carolina

capitol rotunda and Horatio Greenough’s Washington of 1832–41

for the United States Capitol rotunda. There was public disapproval

of these works, and Greenough’s caused a scandal by portraying

its subject as a remote figure in ancient garb. Greenough’s

representation of the president as a half-naked Zeus in a contrived

pose dismayed Americans.

For his Washington, Houdon combined the ancient and time-honored with the current, and tempered classical idealism with a down-to-earth naturalism, creating a version of classical taste that appealed to Americans. Houdon presented Washington as a modern Cincinnatus, the Roman farmer and general who left his land to fight for his state and, after victory, returned to his farm as man of peace and simplicity. In this figure the artist balanced the dualities of military and civil, war and peace, ancient and modern.

Washington wears his uniform but holds a civilian walking cane with his right hand. To the left of and behind the general is a farmer’s plowshare, yet he rests his left hand on a bundle of rods called a fasces, the Roman symbol of civil authority. Houdon translated the symbol to an American usage by forming the bundle from thirteen rods, to stand for the unification of the thirteen original colonies, and adding arrows in between that likely refer to Native Americans or the idea of America as wild frontier. Washington is portrayed as a man, not as a god.

At Mount Vernon, Houdon made a clay bust as a model for his statue. George Washington Bust – Mount Vernon Ladies Association

Stiffly posed and half dressed, Greenough’s Washington found little public favor. Greenough – Smithsonian American Art Museum, transfer from the U.S. Capitol

American interest in antiquity paralleled the French in admiration of the nobility and nostalgia of Rome. But colonial leaders, and particularly Jefferson, admired Rome as a political model as much as a model of virtue. About the time Jefferson was asked for assistance in selecting a sculptor, he had been working on a design for the capitol that would hold Houdon’s statue, and, like the artist, he was looking at ancient sources. The major model for Virginia’s capitol became a Roman temple, the Maison Carrée at Nîmes, France. For Jefferson and his generation of Americans, monumental public buildings in the Roman style, as well as classically inspired art, could serve as examples of taste, virtue, and democracy. By representing Washington as a man of republican Rome, Houdon added a layer of meaning that the new country would surely identify with—great power existing in harmony with democracy.

Houdon soon asked Jefferson for help with the final detail of the commission—Virginia’s plans for the pedestal. The legislature wanted one containing a tribute penned by James Madison:

The General Assembly of the Commonwealth

of Virginia have caused this statue to be erected,

as a monument of affection and gratitude to

GEORGE WASHINGTON;

who, Uniting to the Endowments of the Hero

the Virtues of the Patriot, and exerting both

in establishing the Liberties of his Country

has rendered his name dear to his Fellow-Citizens,

and given the World an immortal example

Of true Glory. ~ Done, in the year of

CHRIST

One thousand seven hundred and eighty eight

and in the year of the Commonwealth the twelfth

The original plan included bas-reliefs as well. No record has been found of the origins of the plan, but it is likely that the model was the statue of colonial Governor Norborne Berkeley, baron de Botetourt, the focal point in the central alcove of the second Williamsburg capitol. The House of Burgesses commissioned English sculptor Richard Hayward for that likeness in 1771. The Botetourt and the Washington are full-length marbles, and the dimensions of their pedestals are close, except that the Botetourt’s is a little more than a foot higher. The Botetourt pedestal also includes a bas-relief and an inscription of similar tone to Madison’s. It appears Washington’s statue was to be an updating of the Botetourt—a centerpiece for a new capitol, and representative of a new government.

Houdon told Jefferson that Madison’s inscription was too long and would make the pedestal too high for ideal viewing of the statue. Jefferson apparently supported Houdon, but Madison and the legislature resisted any change. Houdon sent the base from France, but it arrived as blank slabs of marble. The only inscriptions were on the statue itself: “George Washington” on the front of the sculpture’s base and the artist’s signature and date on the base’s right side. The inscription reads, “Houdon, French Citizen, 1788.” Madison’s inscription was carved onto the front of the pedestal in 1841.

Virginia’s Richmond capitol was under construction when Houdon completed his Washington, so shipment was delayed until the building was ready. Three cases containing the statue and pedestal shipped from France in January 1796 and arrived in Richmond in early May. It received instant acclaim. The statue was erected in the rotunda May 14, 1796. It still stands on the spot it was conceived to fill, and has probably been moved twice, which helps explain the statue’s remarkably good condition.

Washington had been president since 1789, and his popularity had soared. Houdon’s careful recording of Washington’s image and personality yielded a sensitive and lifelike portrait. When the Marquis de Lafayette, Washington’s friend and compatriot, saw the statue for the first time, he said: “That is the man himself. I can almost realize he is going to move.” Washington saw the statue and declared it a accurate likeness of himself.

Houdon’s statue quickly became an authoritative likeness of Washington, a resource for other artists, but its popularity had damaging effects. There was a demand for copies throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries because it was believed Washington’s likeness in public locations would serve as an exemplum virtutis, inspiring beholders with the example of his greatness.

Scott Nolley applied refined clay to draw out stains. Nolley – Library of Virginia Click images to enlarge.

Standing on a raised scaffolding, Colonial Williamsburg conservator Amy Fernandez deployed a battery of cleaning tools and materials. Fernandez – Library of Virginia

The commonwealth authorized casting campaigns to replicate the statue from the late 1840s to 1910. To date, thirty-three bronze and plaster replicas of the Houdon have been permitted. The 2000 conservation treatment discovered that these campaigns did irreparable damage. Breaks in the marble detail were likely the result of the plaster-casting process, and the mold material is permanently embedded in the grain of the marble. The legislature halted the campaigns in 1910 by outlawing the taking of more molds. That protected the statue from additional casting damage, but the piece has also suffered from imperfect environmental conditions and overzealous but well-intentioned cleanings.

Conservation was initiated because the statue looked dirty and had cracks. Tracy Kamerer, curator for the Virginia state art collections, contacted Colonial Williamsburg conservators Scott Nolley and Amy Fernandez to propose the project, and their initial physical examination raised more questions than it answered. At the same time, the curator noted serious gaps in recorded information about the statue’s history and care. During the treatment, the conservator’s physical studies and the curator’s detective work benefited one another.

The Washington statue had not been thoroughly cleaned since 1973, and the preliminary examination showed a marked difference in its appearance from the after-cleaning photography. Conservators found the marble was coated with a mixture of synthetic turpentine and beeswax, a protective treatment commonly used at the time. This coating had darkened and yellowed and trapped dirt and grime. The statue is in a high-traffic area with inconsistent environmental control, and it is frequently exposed to the elements when the portico doors are opened.

Washington’s statue had suffered small losses and cracks, damage to the cane and its tassel being the most noticeable. An explanation for this damage was found in an 1866 newspaper story reporting a pistol duel that resulted in harm to them. Close examination also revealed the cane was original to the piece, but it was fabricated by Houdon as a separate element. We also found the sword handle and guard to have been fabricated separately and attached by the artist. These discoveries disproved the idea that the sculpture had been fabricated from a single block of Carrara marble.

Some of the other damage was not so easily explained. There were patterns of scratches and abrasion, a reduction of surface polish, and stains that had penetrated the stone. The extent of this damage was puzzling; the sculpture is thought to have been moved but twice and has been surrounded by a fence since shortly after its installation. We determined that the major cause of this damage was likely repeated wet cleanings. The curator located a 1930 newspaper article that reported soap and water washings every two weeks during the summer, a schedule described as “twice as many baths as usually required.”

Cleaning alone was not the source of damage, however. Repeated attempts to make plaster casts were very harmful, and delicate details were lost. This was confirmed by the 1866 article. A 1909 article reported casting damage, too. There are small losses to such raised detail as button edges and pocket corners, probably caused when the plaster sections were pulled from the marble surface. Conservators also came to realize that a gray, ingrained ashen material was casting plaster residue that had essentially become part of the stone.

After the extensive examination, conservators began cleaning by vacuuming dust and dirt from the stone surfaces. Conservators identified the coatings, dirt, and grime accumulations and older repair materials and took up the challenge of removing them. Marble is water soluble, but a great deal of the dirt, grime, and staining must be removed using a water-based cleaning system. The conservators developed a custom mix of solvents and detergents, carefully selecting ingredients to clean the marble but protect its delicate surface. Another cleaning method the team used was to coat the stone with refined clay, which draws out stains. That treatment got the attention of capitol visitors, who realized Washington was getting a spa-style facial.

Conservators gave the sculpture a coating of strong microcrystalline wax, which protects against the environment and restores the surface sheen. Conservators found clues to the degree of sheen the sculpture should have from the areas that had escaped past overcleaning. The areas behind Washington’s ears had been washed less often and retained their original luster. As the sculpture’s marble surface gained new gloss by degrees, Houdon’s use of detail and secondary shading reappeared from obscurity. The work was done in public, and the conservation project became a popular educational opportunity and curiosity for visitors and employees.

Throughout the treatment, the collaboration between conservator and curator reconstructed a more complete history and physical record of the Washington statue. We uncovered details about the artist’s technique, the statue’s life in the capitol, and the price of the statue’s popularity.

Houdon’s Washington has played an important role not only in the story of art in America but in the life of Americans. Because of this joint project between the commonwealth and the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, we have a better understanding of the statue’s place in Virginia’s past, and are better prepared for its future.

ADDITIONAL IMAGES

Tracy L. Kamerer is the curator of state art collections for the Library of Virginia in Richmond. Scott W. Nolley, formerly of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, now serves as chief conservator for Fine Art Conservation of Virginia, also in Richmond.