Romancing the Vine in Virginia

No Wine before It’s Time

by Charles M. Holloway

Jamestown Settlement interpreters Michael Lund, Homer Lanier, Steve Martin, and Joseph Freitus, costumed as seventeenth-century sailors, lower a cask of Virginia wine in the hold of the replica Susan Constant as if for shipment to England.

- Dave Doody

The Virginia Company colonists who sailed down the Thames for the Chesapeake in 1606 took along a taste for the grape . . . and for beer, and for aqua vitae, and for Madeira, and for porter, and for Canary, and for sack, and for ale and for drink in most of its forms and flavors, fermented or distilled, in general and in particular. In their time, a time when water was not to be trusted, Englishmen drank per capita forty gallons of alcohol a year. The libation business was in those days lucrative, and no small part of the trade was the wine crossing the Channel from the Continent bound for England’s tables and taverns. It was part of the reason the Virginia Company’s three-ship fleet was making its way to sea.

The merchants and gentlemen of the company who invested in the voyage intended from it to profit. Such things as gold mines and the Northwest Passage were uppermost in the company’s calculations. But commodities figured in its schemes as well. Virginia was set up for a trading colony, and its managers expected from its servants such manufactures as glass, iron, naval stores, silk, and wine. Such New World imports looked to fetch tidy sums.

In the end, it was tobacco that made a market, but in the beginning wine looked more likely. The chronicle of Virginia viticulture thus begins at Jamestown, the scene of many failures and blasted hopes. Its history is sometimes desultory, and it is often discouraging, but 396 years later, the enterprise is at last paying off.

Captain John Smith, who made the four-month trip to the colony with the original 105 settlers, later wrote that at Jamestown there were vines “in great abundance in many parts that climbe the toppes of the highest trees.” The company’s records say Virginia “yeeldeth naturally great store” of grapevines “and of sundry sorts, which by culture will be brought to excellent perfection.” Smith said that “of hedge grapes, we made neere 20 gallons of wine, which was neare as good as your French Brittish,” and that if they were “properly planted, dressed and ordered by skillful ‘vinearoones’ we might make a perfect grape and fruitfull Vintage in short time.” By “vinearoones” he meant vignerons, people who cultivate grapevines.

For decades, however, thirsty Virginians would make do with the much distrusted water, try their hands at home brew and cider, and look for ships from home, like the Mary and John, captained by Samuel Argall. In 1609, Argall “came to truck with the Colony, and to fish for Sturgeon, on a ship well-furnished with wine and other good Provision.” Along the James River shores he found ready customers, settlers often reduced to drinking from the wide muddy tidal stream, and who sometimes paid for the gamble with their lives. In the first year, colonist George Percy wrote, “Our drinke [was] Cold water taken out of the River, which was at a floud verie salt, at low tide full of slime and filth, which was the destruction of many of our men.”

The London Company of Virginia hoped squadrons of Jamestown ships would be freighted with wine and profits. The plans did not bear fruit.

- Dave Doody

After the Mary and John’s departure, the company ordered Sir Thomas Gates, Virginia’s new governor, to “use the labour of your owne men in makinge wines. ” In 1611, Gates’s successor, Thomas Dale, established a three-acre vineyard of such native grapes as scuppernong, or muscadine, and Catawba to test their adaptability for the production of salable wine. The next chief executive, Lord De La Warr, brought Smith’s vignerons. Frenchmen, some of them said the English treated them more like slaves than employees, and none got a wine business going. Their failure was blamed on climate, soil, lack of equipment, and browsing deer.

In 1619, at the meeting of the first representative assembly in English America, Speaker John Pory said, “Three things there bee which in a few yeares may bring this Colony to perfection: the English plough, vineyards and cattle.” The burgesses, sitting in the Jamestown church, passed “Acte 12,” which required colonists to plant vineyards and, to feed silkworms, set out six mulberry trees a year.

Interpreter Dan Hard, delivering goods to Williamsburg’s Raleigh Tavern, draws a mug of wine without falling off the wagon.

Dave Doody

Among the first to comply was yeoman John Johnson, who patented eighty- five acres known as Jockey’s Neck on a plateau four miles east of town. Much of it is now the heart of the Williamsburg Winery, established in 1985, where more than fifty acres are under cultivation. One of its popular vintages is Acte 12 Chardonnay.

But that’s getting ahead of the story. What little wine came of early Virginia efforts was bitter and traveled badly, and to the lack of proper drink was attributed some of the cause of the colony’s failure to approach anything resembling perfection.

In 1622, Governor Francis Wyatt wrote to London:

When we dated our letters in June last, the Colony stood admirably to health, within ten days succeeded great sickness and mortality: This was scarcity and want of meanes: Understand it rightly, want of beere, poultry, mutton &c . . . To plant a Colony by water drinkers was an inexcusable errour in those, who layd the first foundacion, and have made it a received custome, which until it be laide downe againe, there is small hope of health.

Virginians found indeed other beverages to drink their health. As their colony expanded, a modest form of prosperity developed, accompanied by the encouragement of ordinaries, as taverns were sometimes called. In 1649, a writer reported that “six publike Brewhouses” served Virginia and that its 5,000 settlers had plenty of barley and excellent malt and brewed “their owne Beere, strong and good.”

Interpreters Clayton Williams, William Webb, and Bob Brown, left to right, lift a glass in a Raleigh Tavern toast.

- Tom Green

William Byrd of Westover plantation wrote that at Caroline Courthouse, “Colonel Armistead and Colonel Will Beverly have each of ’em erected an ordinary well supplied with wine and other polite liquors,” and “besides these, there is a rum ordinary for persons of more vulgar taste.” Not much later, planter Robert Beverly said, “Their richer sort generally brew their small beer with Malt, which they have from England. . . . the poorer sort brew their Beer with Molasses and Bran. Their strong drink is Madeira Wine.”

Governor William Berkeley, for one, would not give up on the native grape. He experimented with wine growing and bottle making at his Green Springs estate just west of Jamestown. During a visit in 1663, Beverly’s father saw tree plantings that formed a trellis to support extensive grapevines. Berkeley said his wine was “as good as any that came out of Italy.”

Berkeley dispatched Captain Henry Batt to explore western Virginia, and Batt reported that he found “grapes of an incredible Plenty, and Variety, some of which are very sweet” and “grapes so prodigiously large they seem’d more like Bullace than Grapes.” A bullace is a plum.

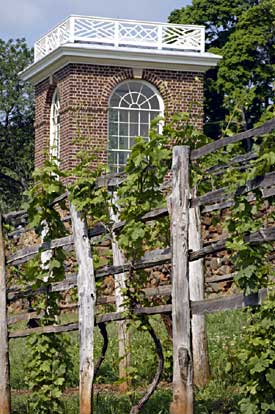

Thomas Jefferson, a wine connoisseur, tried winemaking at Monticello. The picture above shows a modern vineyard adjacent to the house

- .Dave Doody

By the late seventeenth century, most Virginia homes stocked wine and spirits in variety and in quantities exceeded only by such self-produced potations as pear wine and hard apple cider. A 1686 inventory of William Fauntleroy’s cellar in up-country Rappahannock County listed ninety gallons of rum, twenty-five gallons of lime juice, and twenty dozen bottles of wine.

Visitor Durand de Dauphine found that “merrymaking,” including the consumption of large quantities of beer, was extensive. In 1686, he stopped at Bedford, the plantation of William Fitzhugh, and said his host provided “the largest hospitality—he had a store of good wine and other things to drink.” He noticed the local Indians drank no wine, but imbibed beer, cider, and a punch made of beer, brandy, and nutmeg.

Religious and political unrest in France stimulated the emigration of a new wave of colonists, this time Huguenots—Protestants and Calvinists who fled to England in 1685. More than 800, among them vignerons, sailed to Virginia with a Breton nobleman, Olivier de la Muce, and settled above the falls of the James. In 1699, the Huguenots founded Monacan Town and were soon producing wine and brandy, including what they called “a Noble, strong-bodied claret.”

Williamsburg was chartered and became Virginia’s capital the year of Monacan—sometimes Manakin—Town’s founding. In a May Day speech to Governor Francis Nicholson and the General Assembly, a student from the six-year-old College of William and Mary said the city already had many of the essentials of a metropolis, including “a Church, an ordinary, several stores, two Mills, a smith’s shop, a Grammar School, and above all, the Colledge.”

The ordinary may have been John Bentley’s. In 1697 he was licensed to operate a tavern in Captain Matthew Page’s house. Five years later, a Swiss traveler reported that there were eight taverns in the capital. Among their keepers were entrepreneurs like Jean Marot.

Licensed in 1707, Marot’s ordinary, the English Coffee House, became one of Williamsburg’s larger and more popular establishments. Marot operated a couple of stills nearby, and his inventory in 1717 listed such refreshments as Madeira, Canary, red port, Rhenish, brandy, and beer. Later, Henry Wetherburn’s tavern stocked libations like arrack, port, Madeira, claret, beers, and rum.

An idea of the variety of spirits available can be had from the records of an expedition to the west undertaken in 1715 by sixty-three gentlemen known to history as the Knights of the Golden Horseshoe. Among them was John Fontaine, who said the group carried “Virginia red wine and white, Irish usquebaugh, brandy, shrub, two sorts of rum, champagne, canary, cherry, punch, water, cider, etc.”

Hugh Jones, a clergyman who taught mathematics and philosophy at the college from 1717 to 1721, said Madeira was the most popular wine, “for it relieved the heat of summer and warmed the chilled blood and the bitter colds of winter.”

Robert King Carter, the wealthiest Virginian of his day, died in 1732, leaving many of his plantations to his son Charles. Educated in England, the young man wrote a tract on “a whole new system of Virginia Husbandry . . . wherein the business of Tobo farming, improving lands and making Wine, are largely treated of and earnestly recommended.”

Charles Carter became a burgess from King George County, worked with the Royal Society of Arts, and corresponded with Peter Wyche in London, chairman of the society’s agriculture committee. They discussed the production of varieties of French, Spanish, and Portuguese wines in Virginia, though Wyche thought the colony’s location, terrain, and soil made it a less than ideal place to bottle good wines. In 1762, Carter had 1,800 vines in his vineyard but, because of drought, doubted he would produce more than a hogshead of wine.

In 1768, Virginians exported to Britain a little more than thirteen tons of wine while importing 396,580 gallons of rum from overseas, and another 78,264 from other North American colonies.

Bottles and corking equipment in Thomas Jefferson's cellar, which stored imported as well as domestic vintages

- Dave Doody

Two years later, the General Assembly designated Frenchman Andrew Estave winemaker and viticulturist for Virginia. He was described as a long-time resident of France who “hath a perfect Knowledge of the Culture of Vines, and the most approved Method of making Wine.” Estave had lived in the colony two years, studied the soil, and cultivated wild grapes. Now he took 100 acres, a house, and three slaves, promising to make “good merchantable Wine in four years from the seating and planting of the Vineyard.” Like all before him, he failed. Estave thought his stocks of European grapes—vitus vinifera—were too fragile for the climate.

Modern Virginia is a force in winemaking. The wine above was made by Gabriele Rausse Winery of Charlottesville with Monticello-grown Sangiovese grapes.

- Dave Doody

Virginia’s planters looked to London wine merchants for regular supplies—the opposite of what was intended in 1606. George Washington was ordering wines from Robert Cary & Co. in London in 1759. About the time of his wedding to Martha Custis, he asked Cary to “order from the best House in Madeira a Pipe of the best Old Wines.” Two years later, thinking perhaps that he might attempt to grow his own, he ordered “a Butt of about one hundred and fifty gall’ns of your choicest Madeira. And if there is nothing improper, or inconsistent in the request a few setts or cuttings of the Madeira grape.”

Thomas Jefferson’s affinity for French culture and his curiosity led him to plant vineyards at Monticello, and in 1773 he turned over 2,000 acres of rolling land to a Tuscan, Filipo Mazzei, to “prove the value of native grapes.” But Monticello winemaking failed, perhaps because of the advent of the Revolution, or because lice infested the roots and leaves.

Elected president in 1801, Jefferson spent $10,000, a fortune, for wines during his administration, and to hold them ordered a sixteen-foot-deep wine cellar constructed adjacent to the White House. The pit was shaped like a flower pot and built of absorbent clay bricks. A wooden superstructure protected the wine against the weather, and bottles were racked on a platform floor above a bed of ice, replenished monthly and packed in sawdust.

Under Jefferson’s influence, and with the cooperation of wealthy planters, a Virginia winemaking industry began to flower in the early nineteenth century, but the disruptions of the Civil War wiped out the business along with the rest of the state’s economy.

Later in the century, the concept of prohibition gained wide support in Virginia, stifling any revival of winemaking, and by World War I, the state had gone dry. In 1919, the federal Eighteenth Amendment made national the ban on the import, export, manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors.

Virginia’s tidelands became fertile ground for contraband liquor because of its natural resources and access to open water and smugglers’ boats. Sheriffs sought out stills with land, sea, and air patrols. Williamsburg’s Virginia Gazette reported prohibition arrests for moonshining, sale of illegal alcohol, and drunk driving.

After the repeal of the Eighteenth Amendment in 1933, Williamsburg became the first city in the state to end Prohibition, and by 1934 state liquor stores opened. It was not until the mid-1970s that Virginia began to compete again in the national wine market, using French hybrids, vinifera varietals, and new fertilizing techniques that helped counteract disease and mildew. The Farm Winery Law of 1980 boosted the industry, and technical aid from the United States Department of Agriculture and state universities helped accelerate the growth and quality of its product.

At Monticello, Jefferson’s northeast vineyard was replanted in 1985 and his southwest vineyard in 1993. For the past year, visitors to the historic home have had the opportunity to buy—so long as the small supplies lasted—bottles of gift-shop wine.

Vintner Steve Warner samples a barrel at the Williamsburg Winery.

- Dave Doody

There were six Virginia wineries in 1976, and more than seventy by 2002. Virginia ranked tenth in the nation in volume, and its wines were winning national and international acclaim—almost four centuries after the sailing of the first Jamestown fleet.

Charles M. Holloway contributed to the summer 1997 journal “Society of the Cincinnati.”