The Williamsburg Public Armory: A Historical Study

Block 10 Building 22F

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1695

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Williamsburg, Virginia

2004

The Williamsburg

Public Armory:

A Historical Study

Preface

The following study was undertaken during the winter of 2002 and 2003 in response to the possibility of substantial repair or reconstruction of the James Anderson Blacksmith Shop. The basic question I sought to answer was: Who originally constructed the shop on Anderson's block 10 property? This question guided me to a variety of source material, much of which has never been used in the discussion of the James Anderson operation. Each source provided yet another avenue to explore, leading to yet another and another. One thing that all of the sources agree on is the simple fact that the shops constructed on block 10 comprised Virginia's public armory, not James Anderson's blacksmith shop. I have attempted, for your sake and mine, to limit my discussion to the events, atmosphere and personalities which played a role in the construction of what I have come to call the public armory.

Perhaps the most significant result of this project has been the realization that the revolutionary war in Virginia represents a high water mark in the history of trades in Virginia. During the war tradesmen and women, whether they worked at an anvil, needle or plow, played a vital role in keeping state and continental forces in the field. They provided clothing, equipment, housing, food and transportation for the thousands of soldiers, both north and south. Virginia's artisan and farming communities contributed considerably to the ultimate achievement of independence. The revolutionary war also represents a period in which the best documentation of trade activity survives. The names of laborers and master trades people alike, including those enslaved, can be found in the account books of state auditors, quartermasters, commissaries, as well as in the correspondence of Governors, Council, Legislature and the War Office. The clothing, blankets, shoes, tools and personal items they carried and used can be found in the accounting of items they drew from the public stores throughout Virginia. The type and quantity of work they did is enumerated in journals and account books from every office in the newly established state government.

iiThe arguments that follow have been developed through my examinations of the sources listed in the bibliography and through conversations with my fellow trades people. I would particularly like to point out the valuable assistance Master Carpenter Garland Wood has provided in allowing me the substantial time needed to conduct the research and generate this report. Jay Gaynor, Director of Historic Trades, permitted me the time and funds to examine the voluminous Auditor of Public Account records at the Library of Virginia. Ken Schwarz, an expert in the life and work of James Anderson, provided valuable insight into the chronology of the shop and Anderson's relationship with the Virginia government. I would also like to express my appreciation to the Historic Trades Carpentry staff for permitting me to absent myself from the interpretive rotation long enough to compose this report. The staff also suffered through countless hours of my ramblings about the research; ramblings that allowed me to frame my assertions. I particularly would like to thank Jack Underwood for assisting me with my research at the Library of Virginia and suffering with me through volumes of Auditors accounts. As always the staff of the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library was incredibly helpful and assisted me with every request.

What follows is the result of my research. I stand by it, warts and all. I chose to approach this study as if no one had ever examined the subject before; therefore, I have not addressed the historical and archeological studies which have preceded me. I believe archeology should be used to illuminate the historical evidence, not the other way around. I have also avoided references to previous architectural reports, once again preferring to let the documented history of the public armory's construction do the talking. If something has been overlooked or misinterpreted, the fault is mine alone.

Introduction

The years 1776 through 1780 found Williamsburg a very different town than its small permanent population would have remembered it. The city swelled with the arrival of bureaucrats, soldiers and merchants, all arriving to serve the needs of the newly established State of Virginia. Buildings needed to be built or refitted for use as various public offices, barracks established for the hundreds of troops then living out of wooden and canvas tent cities and workshops constructed for the countless trades people hired to furnish the commonwealth with all its material needs. These buildings were not constructed in a vacuum. Political, social and economic conditions all contributed to the materials, labor and quality of the structures built on behalf of the State of Virginia and the United States. The trades people employed in the construction and maintenance of public buildings, as well as those providing material and technical support to the state, were well-respected and established Williamsburg business people. The work they undertook on behalf of the new nation served as physical representations of their skill, craftsmanship and, in some cases, patriotism. This was the multifaceted environment in which public workshops, including the public armory overseen by James Anderson, were constructed.

The advantage to an examination of the history of the construction of the public armory managed by James Anderson is that it was ordered, funded and undertaken by the State of Virginia, through the auspices of the Quartermaster's Department and the State Executive. The status of the armory as a public project provided a substantial paper trail to determine who built it, what materials were available and the ability of the undertakers to obtain the skilled labor necessary for the project. During the period in which the construction of the public armory took place a reorganization of the Virginia government occurred, establishing several offices whose records are useful in understanding the history of the public armory's construction. The establishment of the Boards of Trade and War, with some overlapping responsibilities, as well as 2 the Commissary of Stores and the State Commercial Agent, created the oversight necessary to manage the large number of public workshops needed by the state.1 Along with these state offices, the Continental Congress appointed Williamsburg resident William Finnie as Deputy Quartermaster for the Southern Department, with his headquarters in Williamsburg; Finnie also served as the State Quartermaster for Virginia.2 All of these bodies and individuals interacted with James Anderson and the men who were responsible for the construction of the public armory. Examination of the Quartermaster's records, those of the Board of War, and its successor the War Commissioner, provide information regarding the public armory's construction. The subsequent constructions of public workshops in Richmond, and the public manufactories at Westham and Point of Fork, were also directed by the Commissioner of War, George Muter (and later William Davies). Another source that assists a study of the public armory's construction is the account book of Williamsburg bricklayer and builder, Humphrey Harwood. Last but not least, the wartime account books of James Anderson himself also provide support in a study of the public armory's construction.

There were other factors at play during the years in which the public armory was constructed that effected the materials and methods used to create the building. The scale of felling and processing of wood products, and their subsequent export, speak to the materials that were available to timber merchants in Williamsburg. Timber yards, established on the Williamsburg periphery, became the depositories for these products and supplied the local building trades with the raw materials essential to construction. Williamsburg, while considered a small locality, attracted a skilled and semi-skilled labor pool from which the Williamsburg building community could draw. This population enlarged, rather than decreased, during the 3 germane years in which the public armory was built as the state's demand for skilled labor, white and black, also increased. Virginia and Continental representatives were able to compensate these trades people during the relevant period through the use of newly printed paper money; paper money that would not substantially lose its value until well after the public armory was constructed. Social factors were at play as well; many of the men hired to oversee work for the state were related through their membership in Virginia's Freemasonry community. All of these aspects influenced the construction of the public armory in Williamsburg, aspects that seem to have been overlooked in the past.

Building Material Availability and Acquisition

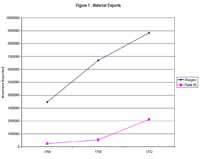

Virginia was an ever expanding territory that necessitated a substantial colony-wide building community of carpenters and joiners and the raw material production required for them to practice their trades. Added to the need of building trades people for raw material was the equally important need of Virginia's farmers for cleared land. The result of these two symbiotic needs was that there was rarely a shortage of suitable timber and plank in the colony; on the contrary, colonial entrepreneurs unable to dispose of all of their timber locally began to view their timber stands as a valuable export commodity. The West Indies, with their small, sugarcane farming intensive islands, afforded the perfect market for the wood products of Virginia and North Carolina. While tobacco continued to be the monetary king of exports, the actual amounts of tobacco shipped paled in comparison with wood products in the years leading up to the American Revolution.3 Among the wood products shipped from Virginia's ports were enormous quantities of roof shingles, planks, scantling (or framing material), logs, barrel staves and heads, trunnels and hoops. This wood product trade, particularly that of shingles and plank, showed a dramatic increase in the years immediately preceding the revolution (Figure 1). Lord Sheffield, in 4 his Observations on the Commerce of the American States, commented that the timber trade immediately prior to the revolution "was supposed to be at its height."4 The recipients of these items were not limited to the British West Indies alone; wood products from Virginia made their way up and down the colonial American coast and to the home islands as well. An accounting of exports from just the Lower James and York River districts for the period February to April 1774 enumerated in the Virginia Gazette demonstrates the vitality of the trade: 905,100 shingles, 37,350 feet of plank and 255,100 feet of scantling.5

5This timber trade, which included a growing number of sawmills along Virginia's fall line, also provided Virginia's urban centers and shipyards with much needed materials. Williamsburg contained at least two timber yards in the years immediately preceding the construction of the public armory; one near the Anthony Hay cabinet shop and another operated by the partnership of James Wray, Jr. and the Jaram family. These timber yards offered woodworkers a diverse selection of building material, sawn to relatively standard dimensions, air dried and ready for delivery.6 Individual woodworkers also maintained substantial quantities of unworked timber that could be converted into useable building material at a later date using smaller, two-man saw pits. Added to the supply of hand sawn material at timber yards and workshops were substantial quantities of mill sawn plank. This plank, rather than being sold by individual merchants in cities like Williamsburg, was typically transported down stream by the mill owners to landings along the rivers in which the mill operated. William Aylett, who was later to serve as Commercial Agent (and therefore the principal purchaser of materials) for the state as well as Deputy Commissary General for the Continent, advertised just such an operation in April of 1774. Aylett claimed that he would send his plank and scantling, consisting of white oak, black walnut, sweet gum, ash, poplar, birch, and the "best" yellow heart pine, to "Norfolk, or any part of York River."7 Purchasers for the Quartermaster's department earned a 2 ½ to 5 % commission on each item purchased or consumed.8 Given the more liberal view of conflict-of-interest the above indicates, it would not be hard to imagine that material used for the construction and repair of public buildings in Williamsburg during Aylett's term as Commercial Agent would have been sawn at his mill in King William County.

6American non-importation and non-exportation resolutions designed to protest parliamentary actions slowed trade with the West Indies. Great Britain retaliated to these American actions by ordering their own trade Restraining Acts in the spring of 1775. Once organized hostilities began, Great Britain issued the Proclamation of Rebellion in 1775 that approved the seizure of American vessels. This was followed by the Prohibitory Act in January 1776, thus officially closing British West Indian ports to Virginia's substantial quantity of wood products.9 This increase in supply doubtlessly led to a decrease in the cost of timber related commodities to the local consumer. That plank and scantling were readily available during the period in which the public armory was constructed is further evidenced by the frequent references to it found in the account books and ledgers of the Auditors of Public Accounts, Deputy Quartermaster William Finnie, Commercial Agent Aylett and the records of the public store kept by William Armistead.10 The accumulation and distribution of plank can also be found in the accounts of James Anderson and Humphrey Harwood as well.11 It is likewise important to note that the principal public stores were in the city of Williamsburg and within two blocks of the site of the public armory. While it is possible that the public stores were depositories for plank, scantling and shingles, more likely the undertaker of the public armory would have received monies or warrants from Finnie or Armistead for the purchase of materials necessary.

Purchases of building materials occurred frequently in the records of all of the principal parties involved in the construction of public buildings. These references are most often to the purchase of plank, scantling, timber or trees. Men paid by William Finnie for providing plank included John Jaram, Samuel Shields, Henry Bresrie, Champion Travis, while the Public Auditors 7 paid warrants to John Hancock, William Smith and Thomas Veal, the latter paid for providing timber and "140 large pine trees." 12 During 1775 and 1776, the soldiers camped in and around the city of Williamsburg were encamped in wooden tents. These tents were created by nailing plank vertically to a horizontal ridge pole, thus creating a wooden version of a common wedge tent. That wooden tents were used is an indication of a shortage of canvas, not plank. Examinations of 18th century sources reveal that the term plank and scantling were terms associated specifically with sawn material. Plank being sawn boards between two and eight inches thick, scantling ranged between three inches square to four-by-ten inches. Timber typically referred to those pieces larger than scantling and often used for sills or summer beams.13

While the work on the public armory was one important undertaking, the principal project in the city was the construction of a substantial barracks, ordered by the Governor's Council in August of 1776.14 The Council wished to have a barracks capable of housing two thousand men, while General Andrew Lewis felt the barracks need only house one thousand.15 Along with the barracks for the infantry, the Council also ordered the construction of another barracks and stable to house the cavalry. The construction of the barracks is integral to any understanding of the construction of the public armory, as the barracks were constructed during the same period, utilizing the same available materials and labor. Therefore, it can be assumed that the workmen and materials being employed in constructing the barracks were also available for the construction of the public armory. Within weeks of the Council's order, Williamsburg bricklayers Humphrey Harwood and William Phillips were paid for brickwork for the barracks totaling nearly £37; therefore indicating that materials were available for construction to begin 8 immediately.16 The total cost for the carpentry and brickwork for the barracks, undertaken by a variety of trades people, exceeded £2000, exclusive of later plastering, repairs and the construction of the stable complex.17

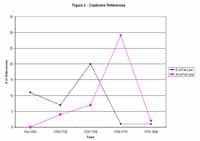

As a final note on the materials available for the public armory construction, one should address the availability or use of short, riven clapboards. While a common material early in the century, by the last quarter of the 18th century it was primarily limited to use on shoddier quality houses and outbuildings.18 There are no references to the purchase or distribution of clapboards in the Commissary of Store's, Commercial Agent's or the Deputy Quartermaster's accounts. Moreover, an examination of references to clapboards in Colonial Williamsburg's Social History Database reveals that 95% of references east of Virginia's fall line occur before 1750 (Figure 2). There is only one reference to the exportation of clapboards during the period 1768 to 1774, and that was for a mere 314 clapboards exported in 1772.19 These facts would seem to argue that the fall line sawmills and the sawyers of the urban timber yards were meeting the substantial demands of the Tidewater region's wood workers.20

9Skilled and Semi-skilled Labor Availability

The decades preceding the American Revolution witnessed an influx of skilled labor, both foreign and native trained, into the city of Williamsburg. In spite of that, a few politically and socially connected masters dominated the Williamsburg building community at the dawn of the revolution. By beginning with an examination of the records of the Committee of Safety for the years 1775 and 1776 one can determine the names of those carpenters who were actively undertaking work for the fledgling State of Virginia. The names of several Williamsburg carpenters21 are found in these records, initially offering their services for items like wooden tents, coffins, tent poles and other minor items.22 Shortly before the decision for independence, the Governor and Council were advised by the Continental Army's southern commander, General 10 Charles Lee, to create "a large body of Carpenters, Smiths, & Artificers" to undertake work for the state.23 Lee's advice led to the continued employment of a number of private trades people, rather than to the establishment of centralized public workshops. The former method, while spreading out the work (and wealth) among a number of individual trade shops, prevented the state from establishing consistent standards of payment or quality. The eventual response was the contracting of a select few shop Masters who were willing to serve the state in the capacity as managers of publicly financed shops. Since the carpentry trade had enjoyed relative freedom from the trade restrictions placed on the metal working trades and British imports, an existing shop was substantial enough to be converted into the "official" state carpenter shop. This titular conversion occurred to Philip Moody's carpenter and joiner shop located on the south side of Francis Street, behind Wetherburn's Tavern.24

Contrastingly, colonial blacksmith shops, hamstrung by limitations placed on them by the Iron Acts of 1750 and 1757, were more modest affairs hardly capable individually of supplying the substantial martial needs of the state.25 The only practical solution was the establishment of a public armory that would be large enough to produce and repair the state's metalwork. An agreement between James Anderson and the Governor's Council was reached in July 1776 for just such an establishment, with Anderson as the state's Public Armorer. The agreement was for the hire of Anderson's existing shop on Botetourt Street, his tools and wages for himself and his workmen.26

11It is important, as one discusses to contracting and appointing of individuals, to address the 18th century attitude towards what today would be termed "a conflict of interest." Dr. John Selby, in his work The Revolution in Virginia, 1775-1783 addresses just this behavior in several pages devoted to the trials and tribulations of the various state and continental agents in Virginia. These men often served as both official purchasers of supplies for the state or continent, as well as representing private firms in competition for the same goods they were expected to acquire for the state. Commissary of Stores William Aylett, in his defense, commented that: "I see no reason why I should move in a sphere truly laborious, and out of the Road of Military legislative or Executive fame, without a reward adequate to the private Sacrifice of Interest it occasions me to make." In other words, "I can still be an avid and industrious provider for the state, while lining my own pockets as well."27 Aylett was not alone; as mentioned above, William Finnie and William Armistead were both receiving commissions on the items they purchased or distributed. James Anderson and Philip Moody, as interested in profit as anyone else, were often issued tools and materials from the public stores that were doubtless used in the private aspects of their respective businesses.28 It would therefore be in keeping with the accepted practices of the day for William Finnie to sanction and fund the construction of a public workshop on private property.

The fluid relationship between private concerns and public service is also represented in the social connections between William Finnie and the trades people who undertook work for him. William Finnie, Philip Moody, Humphrey Harwood, Matthew Anderson (James Anderson's brother) and James Wray, Jr. were all brothers of the Williamsburg Masonic Lodge and James Anderson was later to own the structure in which the Lodge was located.29 When repairs for the lodge were needed the Masons turned to one of their own, Philip Moody, to undertake those 12 repairs and additions. Later, when Moody was the public carpenter, John Lamb undertook repairs to the Lodge.30 The construction of the Williamsburg barracks, ordered by the Council and paid for by Finnie, was undertaken principally by those trades people with Masonic connections. Prominent Williamsburg revolutionaries were also members of the lodge, including James Innes, Peyton Randolph, Edmund Randolph and St. George Tucker.31 Other servants of the Quartermaster's Department also held membership in the Masonic Lodge, among them was prominent Fredericksburg Mason and later Assistant Quartermaster Benjamin Day. Freemasonry membership was a common bond held by many members of the Virginia military establishment; among the most prominent soldier-Masons of Virginia were George Washington, Hugh Mercer, Horatio Gates and William Woodford.32 There were trades people utilized by the Quartermaster's Department, outside the Masonic circle, including John Saunders, who had succeeded James Wray, Sr. as the "college carpenter", Benjamin Powell, a prominent patriot in the Williamsburg community and the Jaram family, partners with Mason James Wray, Junior. Gordon S. Wood stated in The Radicalism of the American Revolution that: "It would be difficult to exaggerate the importance of Masonry for the American Revolution."33 This assertion holds true in an examination of the relationship between Williamsburg trades people and their state, continental and military patrons.

Having determined who the master trades people were that undertook work on behalf of the state, one must establish what labor pool was available for them during a time of war. It has been suggested that, as a result of the need of the state for soldiers, that skilled and semi-skilled labor must have been difficult to obtain. There is very little historical support for this assertion. 13 During the period in which the barracks and public armory was constructed, the only relevant builders who advertised a need for labor were the Jarams. Their need, rather than reflecting a shortage of labor, was more likely a result of their recent arrival (1774) in Williamsburg and the large scale of the operation they were undertaking. That the community provided sufficient labor for the construction needs of the state is also borne out by the fact that the state of Virginia did not exempt artisans from military service, nor did shop masters argue for such exemptions. The state had briefly exempted iron workers from service in the years between May 1778 and May 1781, allowing for artisans to enlist with their Master's permission. It was not until after the capture of Charleston in 1780, and the majority of Virginia's military contingent, did the state begin to truly feel the manpower pinch. Even then, those exemptions were only made for workers in the iron manufactories.34 At no time during the revolutionary war did Virginia exempt carpenters from military duty, and by not doing so demonstrated that the labor pool was significant enough to allow their continued enlistments. One historian has argued that, during the period in which the public armory was constructed, "manpower was not in itself a problem."35

African-American labor, both free and enslaved, was also available to those Masters tasked with public building construction. The Jarams advertised on a number of occasions for "Negro Carpenters" to assist them with their state and private obligations.36 At least one of these men, named Harry, who "when he works at a Bench he works on the wrong side [left-handed]" ran away in April 1777.37 Philip Moody, with his local connections, was able to turn to acquaintances to provide the necessary slave labor. He rented five slaves from his cousin William 14 Moody, Jr. for two months at the beginning of 1779, with the state footing the £111 bill.38 Philip Moody, who was to eventually be appointed the Public Carpenter, employed over thirty men in the public carpentry shop in Richmond by November of 1780.39 Among them were members of other prominent Williamsburg carpenter families including Matthew Hatton, James Taylor, Jr., Daniel McCarty, William Godfrey, Francis F. Moody, Philip Moody, Jr., James Reynolds, and Thomas Hatton.40 The available evidence clearly demonstrates that the skilled and semi-skilled labor needed by carpenters to construct proper buildings was available throughout the revolutionary war.

Money and the Construction of the Public Armory

Much has been made over the years about the inflationary problems faced by revolutionary war governments and correspondingly little has been written about the practical impact of the issuing of paper money had on the ability of the state and continent to supply itself. While there is little question that the issuing of paper money without the backing of silver and gold produced inflation, the growth of inflation during the period in which the public armory was undertaken was relatively slow. It has been argued that the printing and circulating of paper money, regardless of its lack of gold and silver support, actually enhanced the American economy during the early years of the war.

The Continental Congress, by the end of 1776, had over 25 million continental dollars in circulation, while the state of Virginia had printed almost one million pounds in state currency by the fall of 1777.41 This infusion of paper money actually "invigorated and extended the 15 revolutionary movement" and "kept production [for the army] at a high level."42 While one often lingers on the inflationary aspect of the issuing of paper money, "it is doubtful whether the war could have been carried on" without it. Besides, the value of America's, and Virginia's, paper money was only partially based on gold and silver anyway; being also based on "hope that the war would be short and that the American people would be patriotic."43 The eventual rampant inflation was somewhat a response to the amount of currency in circulation but also a realization that the war was to be longer than people had hoped.

Prices for goods, and subsequently labor, began their inflationary rise in late 1778; the Continental dollar at that time traded at five dollars to one of specie. The currency bubble did not truly burst until the end of 1779 when the Continental dollar traded at a further weakened thirty dollars to one of specie ratio. It was not until this inflationary period that members of the Quartermaster's department began to complain to superiors that their lack of adequate funds hampered their ability to do their jobs. The various deputy quartermasters, including Finnie, were forced to agree to terms with suppliers and contractors that were less than favorable to the government, including not fixing the price of items until payment was made. Ostensibly this would include those trades people contracted to undertake the management of the public workshops as well. The Commissary and Quartermaster's department operated on a budget of just over $37 million in 1778, a budget that rose to 200 million by the beginning of 1780.44 The financial situation in Virginia, and the resulting inability of the state to acquire the necessary items of war, did not become of paramount importance to the state's legislators until the fall of 1779.45 Truly debilitating inflation did not begin until the spring of 1781 when the dollar was trading at the astronomical value of 150 dollars to one of specie.46

16The construction of the public armory occurred principally during the months between August 1778 and March 1779, at a time of relatively moderate inflation; approximately four dollars to one of specie.47 While not ideal, this inflation hardly limited the ability of the Quartermasters and Commissaries to purchase the materials and labor necessary to meet the needs of the state and continent. That trades people and suppliers received payments during this period for their work and products is clearly evident in the account books of the Quartermasters, Commissaries and the State Auditors. It has been argued that the American government, and Virginia's, insolvency during this period actually created only minor problems for the vast majority of their citizens.48 Those men that ordered the public armory's construction in 1778, and those that undertook it, were not restricted by the rampant inflation that would grip the country in the years subsequent to the shop's construction.

Historical Evidence for the Construction of the Public armory

Having established which carpenters were undertaking carpentry for the state, one can examine the records of the organizations that would have ordered the construction of the public armory. This naturally led to the records of Deputy Quartermaster William Finnie, the Boards of War, Trade and Navy, and the Governor and Council. William Finnie's Account Book from 1776 to 1780 provides an enormous amount of information on the work undertaken by Williamsburg trades people during the period in which the public armory was constructed. Well established was Humphrey Harwood's construction, in January of 1777, of a forge chimney and underpinning (foundation); less well-known is that Colonel William Finnie ordered this work done. This is confirmed by a listing of payments to Harwood for this forge and foundation construction in Finnie's account book for the month of January 1777. Along with the Harwood entry found in William Finnie's accounts, is one dated the same month: "Paid John Lamb for 17 building a Smith's Shop."49 It is important to note that, while Humphrey Harwood was a prosperous and well known brick maker and layer, he was not the only bricklayer in Williamsburg. While he obviously undertook this January brickwork, he was not the only bricklayer utilized by state and continental quartermasters and commissaries. The names of Samuel Spurr and William Phillips also appear with regularity in the accounts of the state and continental authorities. All of these bricklayers provided services to the Quartermaster's department, often working on the same buildings. Therefore, one must be careful in assuming that Harwood was the only bricklayer to have worked on the construction of the state's public armory.

There has been some discussion about what the above entries mean. Do they represent the first phase of construction on James Anderson's Block 10 property or merely an enlargement of his existing shop to meet the state's growing demands for ironwork. Shortly after this work, in March of 1777, Anderson agreed to undertake smith's work for the State provided he was paid rent for his shop and tools. After discussions with blacksmith Ken Schwarz, it was determined that this first construction phase, undertaken by John Lamb and Humphrey Harwood, was the enlargement, at public expense, of Anderson's existing Botetourt Street shop. This enlargement allowed Anderson, initially at least, to meet the needs of the state. The exact date Harwood began laying the foundation at Anderson's is unclear, but it must have occurred sometime between October 1776 and the date he was paid for the work in January 1777. Harwood charged the state just over two pounds for the construction of the forge chimney and foundation.50 John Lamb's carpentry work on the shop amounted to just over £41.51 Meanwhile, as mentioned previously, construction of the barracks continued, undoubtedly with material being manufactured in Anderson's shop or purchased from merchants or other smiths working in Williamsburg. Anticipating his new ability to meet the needs of the state, Anderson contracted with the Virginia Council to "do the blacksmith's work for the Commonwealth" with his "two forges and five 18 apprentices."52 That Anderson's Botetourt Street shop was a quasi-public workshop by July 1777 is indicated by it being referred to as the "Public Armoury [sic]," with James Anderson as its manager, appearing in the journal of the Williamsburg public store.53 Throughout the spring and summer of 1777 carpenters continued to be employed in the construction of the barracks and refitting of other buildings for public use. The state had, by the end of 1777, paid out over two thousand pounds to Philip Moody, John Saunders and John Lamb for their part in the construction of the barracks; work likely including all the carpentry, as well as "shingles" for the roof.54 The demands on James Anderson's shop increased during this period as well and, by December 1777, his shop was being provided with £32 per month for nine smiths.55 James Anderson, and apparently William Finnie as well, saw no ethical roadblocks to the state's funding of enlargements to Anderson's private shop and this pattern would be repeated in the later construction of the armory buildings on Anderson's Block 10 lot.

The work on the barracks wound down in 1778, amounting primarily to repairs done to the barracks here and there, but the demand for carpentry work and blacksmithing work continued unabated; the state required cannon carriages, arms repair and the ephemera of war. The continued call for metalwork demanded either another enlargement of Anderson's existing shop or the construction of an entirely new structure. The state apparently decided on the latter, preferring construction of a shop specially made to undertake the diverse metalworking needed by the country. James Anderson's Block 10 lot appealed to the authorities as the building site undoubtedly due to its close proximity to the public stores, magazine and Philip Moody's public carpenter shop. Moody had been constructing gun carriages and wagons for the state for some 19 time, both of which required substantial ironwork. That the state would undertake the construction of a completely new armory complex in Williamsburg as late as 1778 is a clear indication that the prospect of the capitol leaving Williamsburg at the time must have been insignificant. Construction of the armory must have begun during the late summer and early fall of 1778. During that period James Anderson recorded in his account book that he delivered nails to carpenter Philip Moody56 for the "Armourer's[sic] Shop."57 Humphrey Harwood, in November 1778, charged the state for work done at the public armory, including the addition of a new chimney to the shop.58 Again, when this work actually took place is unknown, only that it must have occurred sometime prior to the date on which Harwood recorded the charge in his ledger. Anderson, during November 1778 as well, purchased fifteen pair of hinges from Williamsburg merchant George Reid "for his shop."59 Moody, during the fall of 1778, drew from the public store rope, files and gimlets, while receiving from Anderson thousands of eight, ten and twenty penny nails.60

The second phase of construction occurred during the late winter of 1778 and spring of 1779. Humphrey Harwood was paid for repairing existing chimneys, constructing three more forge chimneys and a new foundation at the Block 10 property.61 Between 1 January and 1 April 1779, Philip Moody was paid over £467 for work conducted for the state.62 As Moody was overseeing the public carpentry shop as a whole, the money undoubtedly was for work conducted 20 at the shop as well as work done on the public armory. Moody also used the state schooner Mayflower in February of 1779 to obtain plank for state use and in April 1779 Moody acquired a further 2710 feet of plank "for the use of the State" from none other than James Anderson.63 Moody, for the finishing touch, purchased £87 worth of shingles from Jonathan Morning "for Public Use."64 Philip Moody, a Williamsburg trained carpenter, constructed the public armory utilizing those materials and methods typical of Williamsburg buildings. Following this enlargement of the shop Anderson increased his labor force by acquiring the use of state owned slaves and five apprentice nailors.65

Post-Williamsburg Armories

The timeline for the construction of Williamsburg's public armory determined, one is left to agree on what the structure looked like and how it was organized. The information above provides evidence of the materials used in the armory's construction and therefore offers some guidance as to appearance, but other sources are helpful as well. Following the raid and destruction of stores at Portsmouth and Suffolk by British Major General Edward Mathew and Commodore Sir George Collier on 8 May 1779, the Virginia General Assembly determined to move the capitol to a location they believed offered better defensibility.66 This raid provided all the evidence needed to manifest that the eastern frontier of Virginia was difficult, if not impossible, to defend against an enemy with control of the sea. Those up-country legislators who had been arguing for a capitol more centrally located found their arguments strengthened by the actions of Mathew and Collier. The decision to move the capitol was based on the assertion that the capitol should not be in an exposed location were the enemy could easily descend upon it 21 from the sea. Prior to the Mathew-Collier raid, legislators were able to convince themselves that Williamsburg was safe, subsequent to the raid that position was no longer tenable.67

Abandoning Williamsburg was no trivial decision however. Considerable sums of money had been expended in the public buildings constructed and refitted for the state's use during the previous four years. Williamsburg was not immediately deserted however when the decision to move the capitol to Richmond was made. The public buildings needed to house the various public officials and legislators did not exist in Richmond, nor did the workshops and barracks necessary to house the artisans and soldiers. While existing structures in Richmond could serve the needs of the state temporarily, ultimately the state would require another building program similar to the one which Williamsburg had witnessed during the years prior to the move. As discussed above, the state could not have, fiscally anyway, selected a worse time to undertake the construction of an entirely new capitol city. By the summer of 1779, the inflationary crisis was beginning to take hold making it increasingly difficult for state purchasers to acquire materials and goods. Another challenge was that the substantial building community found in Williamsburg was absent in the smaller, less developed city of Richmond. Richmond, with an approximate population of only about 700 souls in 1775 and the rural nature of its commerce had no need for the significant community of trades people found in Williamsburg.68

The only logical conclusion was that the trades people who had overseen the public workshops in Williamsburg, as well as the bulk of their workers, should move with the capitol to Richmond. The Board of War contracted with Philip Moody to oversee the public carpenters in Richmond in March 1780, and continued to employ Anderson as the manager of the new public armory to be constructed in Richmond.69 Moody, in his continuing role as the Public Carpenter, undertook the construction of the new workshops in Richmond while continuing to operate his 22 shop in Williamsburg as well. Even as the value of currency deflated, material for Moody's carpenters was still readily accessible as his continued production indicated. Construction on Anderson's shops had obviously already begun by July of 1780, for that month Granville Smith, Assistant Quartermaster General in Williamsburg, was ordered by the War Office to have Anderson's "tools, anvils, etc." sent to Richmond as soon as possible; meanwhile the manager of the Public Foundry at Westham, John Reveley, was ordered to provide Anderson with coal.70 The War Office placed considerable importance on the construction of the new public armory, ordering Moody to use his "best endeavors" to build "Anderson's shops" according to the "plans" that are "herewith delivered to you."71 That Moody had been provided with plans for the armory demonstrates that the building was not intended to be a crudely executed structure. Moody was continuing to operate the shop in Williamsburg as well as undertaking the new work in Richmond but was eventually ordered by Commissioner of War George Muter to remove himself permanently to the capitol. Building the "shops & providing for building the houses immediately wanted" required Moody's presence in the new capitol. Particularly of concern to Muter was that "the sashes for Mr. Anderson's shops have never yet been begun", thus clearly indicating that sash was an important aspect of the design for the new public armory in Richmond.72 The work on Anderson's shop must have progressed quickly upon Moody's arrival in Richmond, as there are no further worrisome letters from Muter to Moody.

The public armory in Richmond was apparently completed by the time a British expedition under the command of General Benedict Arnold and Lieutenant Colonel John Graves Simcoe attacked Richmond on 5 January 1781. British intentions, whether during the Mathew 23 Collier raid of 1779 or the campaign of 1781, were to destroy Virginia's ability to supply the Continental Army with material and supplies. The result of this policy was that British troops destroyed, or rendered useless, those structures that would permit Virginia to manufacture or repair war material. During the January raid of Richmond and Westham, British forces marched "to the foundery [sic] at Westham" to "destroy it."73 They also destroyed a number of supplies and tools at Moody's shop in Richmond, as well as causing damage to the public armory and magazine.74 The damage to the public armory must have been severe for following the raid on Richmond and Westham, Moody was once again ordered to "have a [shop] fitted up for Mr. Anderson. . .without a moments of time."75 Once again material availability appeared not to be a substantial problem, as the Quartermaster's department was ordered to provide Moody with timber for Anderson's new shop "as quick as possible"; in the meantime, Moody continued producing wood items for the state, apparently little effected by the loss of some of his tools.76

This pattern of the destruction of Virginia's public workshops continued during the subsequent raids in Tidewater Virginia by forces under the command of British General Williams Phillips. Phillips, during April 1781, briefly occupied Williamsburg, and sent a raiding party under Lieutenant Colonel Simcoe to Yorktown where they burned "a range of the rebel barracks."77 While there is little direct evidence, it is likely that the occupying force under Phillips took the opportunity while in Williamsburg to destroy the public workshops and barracks there as well. Phillips, in a letter to Lafayette immediately after his occupation of Williamsburg, stated 24 that he was undertaking "the necessary destruction of public stores of every kind." Phillips also wanted to make clear to Lafayette his commitment that he would "prevent, as far as possible, that [destruction] of private property."78 This desire to limit the damage to private property provides an explanation as to why the public armory buildings appear apparently intact on the Frenchman's Map of 1781. Other public workshop sites, including Philip Moody's and the Hay Cabinet Shop (used by Anderson as a gun repair facility) are noticeably absent from the Frenchman's Map. The armory's centralized location in the city made destruction by fire dangerous; therefore, to render the public armory incapacitated, the British merely needed to destroy the forges. Once this was done, the building was no longer capable of functioning effectively as an armory. That Phillips was successful is his endeavor to render Virginia's war manufactures a serious blow is further seen in a letter from Deputy Quartermaster General for Virginia Richard Claiborne to Lafayette in May 1781. Claiborne informed Lafayette that manufactures at "Alexandria, Fredericksburg, Williamsburg, Richmond, Petersburg & Chesterfield Court House have all been either broke up by the enemy or the business unfixed in such a manner that it will be almost impossible to establish them in any short time..."79

Verification that the British in Williamsburg did exactly what Phillips claimed is the fact that the barracks were in ruins and the public workshops "broke up" by the time the combined Franco-American forces arrived in Williamsburg in the late summer of 1781. The destruction of the public armory's forges by the British is further evidenced by the randomly-priced repair work undertaken on the site for James Anderson by Humphrey Harwood after 1783. This work, rather than representing the construction of entirely new forges and chimneys, was more likely work 25 undertaken to repair the damage done by the British in 1781.80 While the Tidewater had previously proven itself indefensible, the destruction of the public workshops as far inland as Richmond and Westham convinced the Virginia government that the state shops should be placed even farther west. They eventually decided on a tip of land where the James and Rivanna Rivers join, Point of Fork, to establish their new manufacturing enterprises.

Construction on the workshops at Point of Fork was initially undertaken once again by Philip Moody, but his time as the Public Carpenter was coming to an end. While Moody continued to oversee work in Richmond, Milton Ford had been placed at Point of Fork in early 1781 to convert existing buildings into storehouses for the state. Milton Ford was the son of Williamsburg carpenter, and by this time Amelia County resident, Christopher Ford. Moody had served his apprenticeship with Christopher Ford in the early 1750's, and likely knew Milton Ford personally.81 Philip Moody, for reasons unknown, ended his association with the state in April or May 1781 and the state turned entirely to Milton Ford to oversee the construction of the new facilities at Point of Fork. Ford called on his brother Samuel and father Christopher to assist him in the construction of the public workshops and storehouses at Point of Fork.82 Anderson, at the beginning of April 1781, was ordered to provide Ford with one hundred thousand nails "to carry on the works at Point of Fork."83 Once again Virginia turned to Williamsburg trained and practiced artisans to undertake the construction of public workshops and buildings.

Point of Fork, in spite of its seemingly remote location, proved no safer from British attack than any other point in Virginia. The British were capable of reaching out to the farthest reaches of the navigable rivers in their efforts to limit Virginia's ability to succor the Continental 26 Army. Once again, this time with Cornwallis as his minder, Simcoe was given orders to raid the stores and workshops of the state. The Queen's Rangers arrived at Point of Fork on 5 June 1781 and found barracks, blacksmith shops and the recently raised armory frame. Simcoe's men destroyed a number of arms and supplies, a hoard of carpenter tools, burned the barracks but negligently left the blacksmith shops and the armory frame untouched.84 Despite all of the subsequent debate regarding the loss of stores at Point of Fork, Simcoe's error in leaving the bulk of the workshops intact meant that the Point of Fork manufacturing capacity was only minimally impacted by the raid. Perhaps the most substantial impact of the raid was not the loss of state stores but the capture of James Anderson by the Queen's Rangers.85

Towards the end of the war, the War Office of the United States determined in the spring of 1783 to turn the Virginia Point of Fork site into a federal arsenal. Samuel Hodgdon, Commissary of Military Stores, provided the Secretary at War Benjamin Lincoln with a detailed estimate of the cost of three buildings at Point of Fork: a magazine, arsenal and laboratory. One can assume that, by 1783, the prototypes for these buildings could be found in those previously constructed in Williamsburg and Richmond. In spite of Point of Fork's remote location, the plans still called for walls of brick, sawn oak framing material of uniform dimensions, thousands of shingles, long leaf yellow pine framing for door and window frames, twenty thousand feet of one inch heart pine floorboards, lined shutters and doors, cornice and fascia, forty six sets of hooks and hinges for windows, eight sets of the same for doors and painting.86 These buildings, in the backcountry of Virginia, were constructed in a style recognizable to Williamsburg builders like Philip Moody and Christopher Ford.

Conclusion

The current state of the Anderson Blacksmith Shop affords the Foundation with the opportunity to reexamine both the historical and architectural information presented on the site. Given the information presented above, it would appear that the Foundation should reconsider the design and interpretation of the site. This was no rural building, nor was it "Anderson's Blacksmith Shop." The building constructed on James Anderson's Block 10 lot was a publicly funded and undertaken shop, operated by James Anderson on contract with the state and providing the essentials of war to both the Commonwealth and Continent. Williamsburg builder Philip Moody was the most probable builder of the state owned, James Anderson operated, public armory. Moody was a respected member of the community, as evidenced by his being a senior member of the Masonic Lodge, his ability to obtain labor without needing to advertise and a customer base that included the Prentis and Waller families. That the state was pleased with Moody's workmanship is indicated by Moody's later elevation to Superintendent of Artificers (woodworkers) and his construction of public buildings in Richmond, Yorktown, Portsmouth and Westham. Perhaps the best testament to the abilities of Moody and his men, as well as to the overall quality of work being done by public carpenters during this period comes from an unlikely source. The Chevalier Dupleix de Cadignan, Lieutenant Colonel of the Agênois Regiment commented upon his arrival in Williamsburg in 1781 that the British had burned the barracks, "magnificent buildings…erected outside the town."87 This is a considerable statement coming as it did from a professional French officer familiar with the finest military architecture in Europe. While there is unfortunately no such reference to the public armory, one should assume that it was built according to the high standards of one of Williamsburg's most successful 29 carpenters, who used materials and labor consistent with his locale. Joseph J. Ellis, in his study of Jefferson's character, noted that historians are not "obliged to disavow the use of their imaginations but were duty-bound to keep them on a tight tether tied to the available evidence."88 Given the available evidence presented above, perhaps now is the time to revisit our imaginations.

Footnotes

Bibliography of Sources Used

The following bibliography includes all sources examined in the historical study of the construction of the public armory. This listing includes sources that, while examined, may not have been noted in the text for a variety of reasons. However, all of the sources listed below were useful in obtaining a more complete understanding of the construction of the public armory in Williamsburg. It is hoped that, by listing these sources here, it will allow the reader to obtain a better grasp of the volume of sources that are available to the researcher examining the history of Williamsburg artisan community during the Revolutionary War.

- Deputy Quartermaster General, Southern Department, Accounts 1776 - 1780. The Library of Virginia, Richmond. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Freemasons Lodge Proceedings (Williamsburg Masonic Lodge). Photocopied Manuscript, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Harwood, Humphrey. Account Book, Folio 1 - Folio 5. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Lewis, Andrew. Orderly Book. Photostat copy, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Papers of the Continental Congress. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Records of the Public Store in Williamsburg, 1775-1780, Day Book Nov. 14 1778 - July 12, 1780. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Schwarz, Ken ed. James Anderson Wartime Account Book. Manuscript, Daughters of the American Revolution Library, Daughters of the American Revolution.

- United States. Continental Army. Quartermaster's Department. Letters, Returns, Accounts, and Estimates of the Quartermaster General's Department, 1776-1783. Microfilm. National Archives, Washington, D.C.

- Virginia. Accounts of the Military Store, Richmond, 14 June - 30 Nov. 1780. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Virginia. Auditor of Public Accounts, 1776-1928, Copies of Accounts Settled by State Auditors, Ledger, 1777-1787. State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- Virginia. Auditor of Public Accounts, 1776-1928, Disbursements Ledger, 1778 - 1779. State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia. Richmond.

- Virginia. Auditor of Public Accounts, 1776-1928, Ledger, 1779 - 1813. State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia. Richmond.

- Virginia. Auditor of Public Accounts, 1776-1928, Militia and Contingent Account Book, 1776-1778. State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia. Richmond.

- Virginia. Auditor of Public Accounts, 1776-1928, Pay Vouchers, 1781-1868. State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- Virginia. Auditor of Public Accounts, 1776-1928, Point of Fork Arsenal Records, 1783 - 1803. State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- Virginia. Auditor of Public Accounts, 1776-1928, Receipts and Disbursements, General Ledgers, 1778 - 1928, Volume A, 1778-1781. State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- Virginia. Auditor of Public Accounts, 1776-1928, Receipts and Disbursements, Journals, 1778 - 1797. State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- Virginia. Auditor of Public Accounts, 1776-1928, Receipts and Warrants, March - July 23, 1779. State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- Virginia. Division of Buildings and Grounds, Capitol Square Data, 1779-1932. Accession 24374, State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- Virginia. General Assembly, Council Warrants, 1781 - 1783. Accession 38057, State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- Virginia Governor (1776 - 1779: Henry), Executive Papers: Letters Received, 1776 - 1779. Accession 29604, State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- Virginia Governor (1779 - 1781: Jefferson), Executive Papers: Letters Received, 1779 - 1781. Accession 29604, State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- Virginia. Orders on the Public Store, July 1779 - Oct. 1779. The Library of Virginia, Richmond. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Virginia. Public Store Papers, Williamsburg 1779-1780. The Library of Virginia, Richmond. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Virginia. Records of the Public Store 1775-1780, Day Book, October 12, 1775-November 30, 1778. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Virginia. Records of the Public Store 1775-1780, Journal, 1775-1780. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Virginia. Records of the Public Store in Williamsburg, 1775-1780, Day Book, Nov. 14 1778 - July 12, 1780. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Virginia. State Agent's Loose Papers, 1775-1778. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Virginia. Treasurer's Office Records, Cash Book, 15 January 1777 - 6 April 1777. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Virginia. War Office, General Correspondence, 1780 - 1782. State Government Records Collection, The Library of Virginia, Richmond.

- Virginia. War Office Letter Books, 23 December 1779-5 May 1782. The Library of Virginia, Richmond. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Virginia. War Office Papers, Journal, 18 January - 31 December 1781. The Library of Virginia, Richmond. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- Virginia Gazette. Williamsburg. Photostat copies, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. 31

- York County Records Project, Biographical File, Moody, Humphrey - Morrison. Microfilm, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Primary Sources:

- Beatson, Robert. Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain from 1727 to 1783. London: Longman, Hurst, Rees and Orme, 1804.

- Bently, Elizabeth Petty ed. Virginia Military Records from the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography, the William and Mary College Quarterly, and Tyler's Quarterly. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Co., Inc., 1983.

- Boyd, Julian P., ed. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Volume 3, 18 June 1779 to 30 September 1780. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951.

- Boyd, Julian P., ed. The Papers of Thomas Jefferson, Volume 4, 1 October 1780 to 24 February 1781. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951.

- Hening, William Waller. Statutes at Large Being a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia, Volume IX. Richmond: J. & G. Cochran, 1821; reprint, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1969.

- Hening, William Waller. Statutes at Large Bring a Collection of all the Laws of Virginia, Volume X. Richmond: J. & G. Cochran, 1822; reprint, Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1969.

- Idzerda, Stanley, ed. Lafayette in the Age of the American Revolution, Selected Letters and Papers, 1776 - 1790, Volume IV, April 1, 1781 - December 23, 1781. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1981.

- McIlwaine, H.R. ed. Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia, Volume 1, July 12, 1776 - October 2, 1777. Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1931.

- McIlwaine, H.R. Journals of the Council of the State of Virginia, Volume II, October 6, 1777 - November 30, 1781. Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1932.

- McIlwaine, H.R. ed. Official Letters of the Governors of the State of Virginia, Volume I, Letters of Patrick Henry. Richmond: Virginia State Library, 1926.

- Mullins, Melissa A., French Soldiers and Officers in Williamsburg, 1781-1782. Williamsburg: Research Report, 1990.

- Palmer, William P., ed. Calendar of Virginia State Papers and other Manuscripts, 1652 - 1781, Volume I. Richmond: Legislature of Virginia, 1875; reprint, New York: Krause Reprint Corporation, 1968.

- Palmer, William, ed. Calendar of Virginia State Papers and Other Manuscripts, 1652-1781, Volume VIII. Richmond: Legislature of Virginia, 1890; reprint, New York: Krause Reprint Corporation, 1968.

- Simcoe, John Graves. Simcoe's Military Journal, A History of the Operations of a Partisan Corps, called The Queen's Rangers, Commanded by Lieut. Col. J.G. Simcoe, During the War of the American Revolution. New York: Bartlett & Welford, 1844; reprint, New York: Arno Press, 1968.

Printed Primary Sources:

- Boatner, Mark. Encyclopedia of the American Revolution. Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1994. 32

- Buchanan, Paul and Catherine Savedge. Masonic Lodge (Not Owned) Architectural Report, Block 11, Building 3A, Lot 13. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Research Report Series - 1235, 1971.

- Bullock, H. The Magazine (LL) Historical Report, Block 12, Building 9, originally entitled: The Powder Magazine. Research Report Series. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1990.

- Carrington Selwyn H.H. The British West Indies During the American Revolution. Dordrecht and Providence: Foris Publications, 1988.

- Crouch, Richard. "The Point of Fork Arsenal: Fluvanna County's Revolutionary Landmark." The Bulletin of the Fluvanna County Historical Society 4 (March 1967): 1-12.

- Davis, Robert P. Where a Man Can Go, Major General William Phillips, British Royal Artillery, 1731 - 1781. Westport and London: Greenwood Press, 1999.

- Ellis, Joseph J. American Sphinx, The Character of Thomas Jefferson. New York: Vintage Books, 1996.

- Foner, Philip S. Labor and the American Revolution. Westport and London: Greenwood Press, 1976.

- Gill, Harold B. Artisans in Williamsburg 1700 - 1800. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Report Series, 1994.

- Heaton, Ronald E. Masonic Membership of the Founding Fathers. Silver Spring, Maryland: Masonic Service Association, 1974.

- Higginbotham, Don. The War of American Independence, Military Attitudes, Policies, and Practice, 1763 - 1789. Boston: Northeastern University Press, 1971.

- Hollowell, M. Edgar. "The Point of Fork Arsenal." Military Collector and Historian 22 (Spring 1970): 11- 13.

- Hume, Ivor Noël. James Anderson Archaeological Report. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1977.

- Kidd, George Eldridge. Early Freemasonry in Williamsburg, Virginia. Richmond: Dietz Press, 1957.

- Lounsbury, Carl R. ed. An Illustrated Glossary of Early Southern Architecture and Landscape. Charlottesville and London: University Press of Virginia, 1994.

- McBride, John David. The Virginia War Effort; 1775 - 1783: Manpower Policies and Practices. Ph.D. Dissertation: University of Virginia, 1977; microfilm reprint, Ann Arbor: University Microfilms International, 1985.

- McGegee, Minnie Lee, ed. "Point of Fork Arsenal in 1781." The Bulletin of the Fluvanna County Historical Society 25 (October 1977): 1-21.

- McGegee, Minnie Lee, ed. "The Revolutionary War in Fluvanna." The Bulletin of the Fluvanna County Historical Society 24 (April 1977): 1-29.

- Mackesy, Piers. The War for America, 1775-1783. Lincoln and London: The University of Nebraska Press, 1992.

- Miller, Beverly Wellings. The Export Trade of Four Colonial Virginia Ports, 1768. Master of Arts Thesis: College of William and Mary, 1967.

- Miller, John C. Triumph of Freedom, 1775 - 1783. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1948. 33

- Pitman, Frank Wesley. The Development of the British West Indies, 1700 - 1763. New London: Archon Books, 1967.

- Poirier, Noel B. "The Colonial Timberyard in America." The Chronicle of the Early American Industries Association. 54 (June 2001): 54-59.

- Poirier, Noel B. Philip Moody Chronology, 1753 - 1800. Unpublished Research Report, 2003.

- Risch, Erna. Special Studies: Supplying Washington's Army. Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1981.

- Rutyna, Richard A. and Peter C. Stewart. The History of Freemasonry in Virginia. Lanham and New York: University Press of America, 1998.

- Sargent, Charles W. Virginia and the West Indies Trade, 1740-1765. Ph.D. Dissertation, The University of New Mexico, 1964; Reprint Ann Arbor: University Microfilms, Inc., 1965.

- Selby, John E. A Chronology of Virginia and the War of Independence 1763 - 1783. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1973

- Selby, John. The Revolution in Virginia 1775-1783. Williamsburg: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1988.

- Sheffield, John Lord. Observations on the Commerce of the American States. (1784: Reprint, New York, Augustus M. Kelley, 1970.

- Schupp, Katherine W. Anderson's Blacksmith Shop: A Case for the Tinsmith Among the Anvils. Williamsburg: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Department of Archaeological Research, 2002.

- Soltow, James H. The Economic Role of Williamsburg. Williamsburg: The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1956.

- Soltow, James H. The Occupational Structure of Williamsburg in 1775. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Research Report, 1956.

- Stephenson, Mary A. James Anderson House Historical Report, Block 10, Building 22, Lot 18. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1961; reprint, Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, 1990.

- Stephenson, Mary A. William Finnie House Historical Report, Block 2 Building 7 Lot 257, Originally entitled Semple House, Block 2, Colonial Lot 257. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series-1011, 1964.

- Stewart, Peter C. "Elizabeth River Commerce During the Revolutionary Era," as found in Richard A. Rutyna and Peter C Stewart, ed. Virginia in the American Revolution, A Collection of Essays, Volume I. Norfolk: Old Dominion University, 1977.

- Upton, Dell. Report on the Proposed Reconstruction of James Anderson Forges. Williamsburg: Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Research Report, 1981.

- Walsh, Richard. Charleston's Sons of Liberty, A Study of the Artisans, 1763 - 1789. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1959. 34

- Ward, Harry M. and Harold E. Greer, Jr. Richmond During the Revolution, 1775 - 83. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1977.

- Wood, Gordon S. The Radicalism of the American Revolution. New York: Vintage Books, 1991.

Secondary Sources:

The bound version of this report in the John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Library contains an illustration with the heading "Wooden tent built with cratchet supports, pictured in the German military manual Was ist jedem Officer wahrend eines Feldzugs zu wissen noethig (trans., "What it is necessary for each officer to know during a campaign"), Carlsruhe, 1788. (Courtesy of Charles Beale.)". This illustration was not included in the electronic version of the report, and is not available.