The Ravenscroft Site:

Archaeological Investigation of Colonial Lots 267 and 268

Graphics:

Heather M. Harvey

Principal Investigator:

Marley R. Brown III

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation

Department of Archaeological Research

June 1998

Management Summary

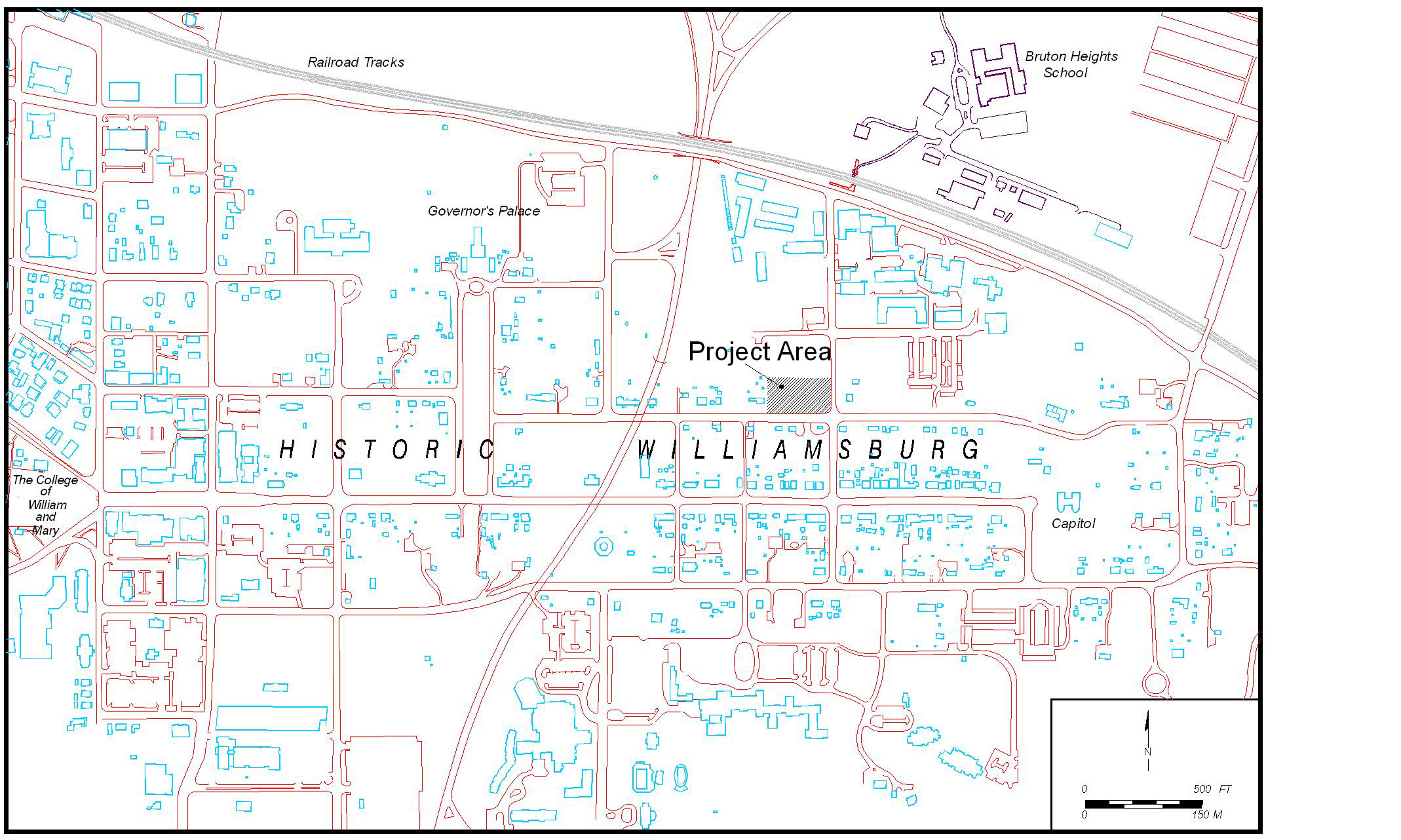

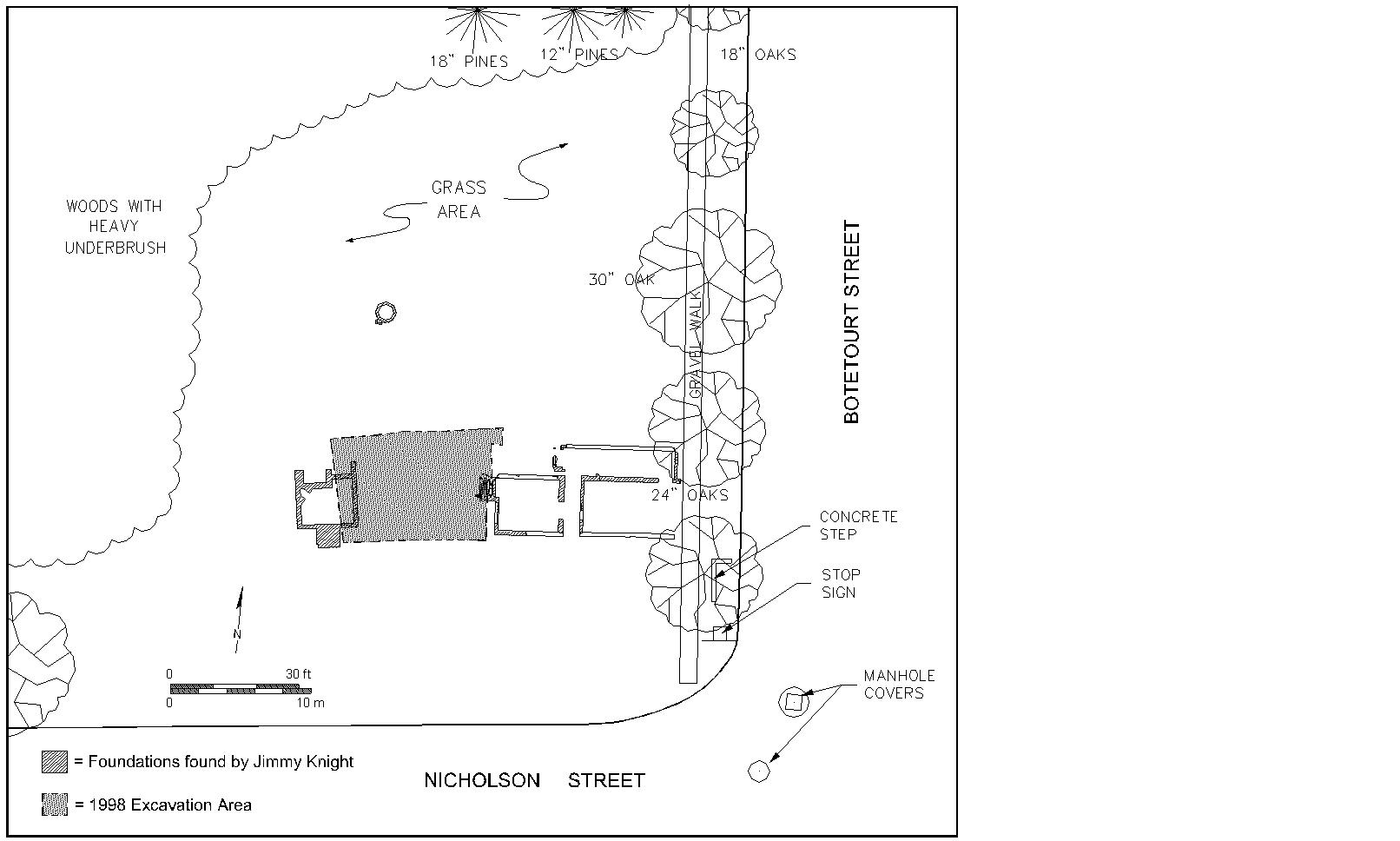

From January 12 to February 3, 1998, excavations were performed on the site of a proposed reconstruction of a tenant house on the northwest corner of Botetourt and Nicholson Streets in Williamsburg, Virginia (Figure 1). These excavations were recommended by the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Archaeological Research after the area had been surveyed for intact archaeological remains endangered by the construction of this proposed exhibition building. Historical and archaeological information led the archaeologists to believe that this site contained valuable historic resources.

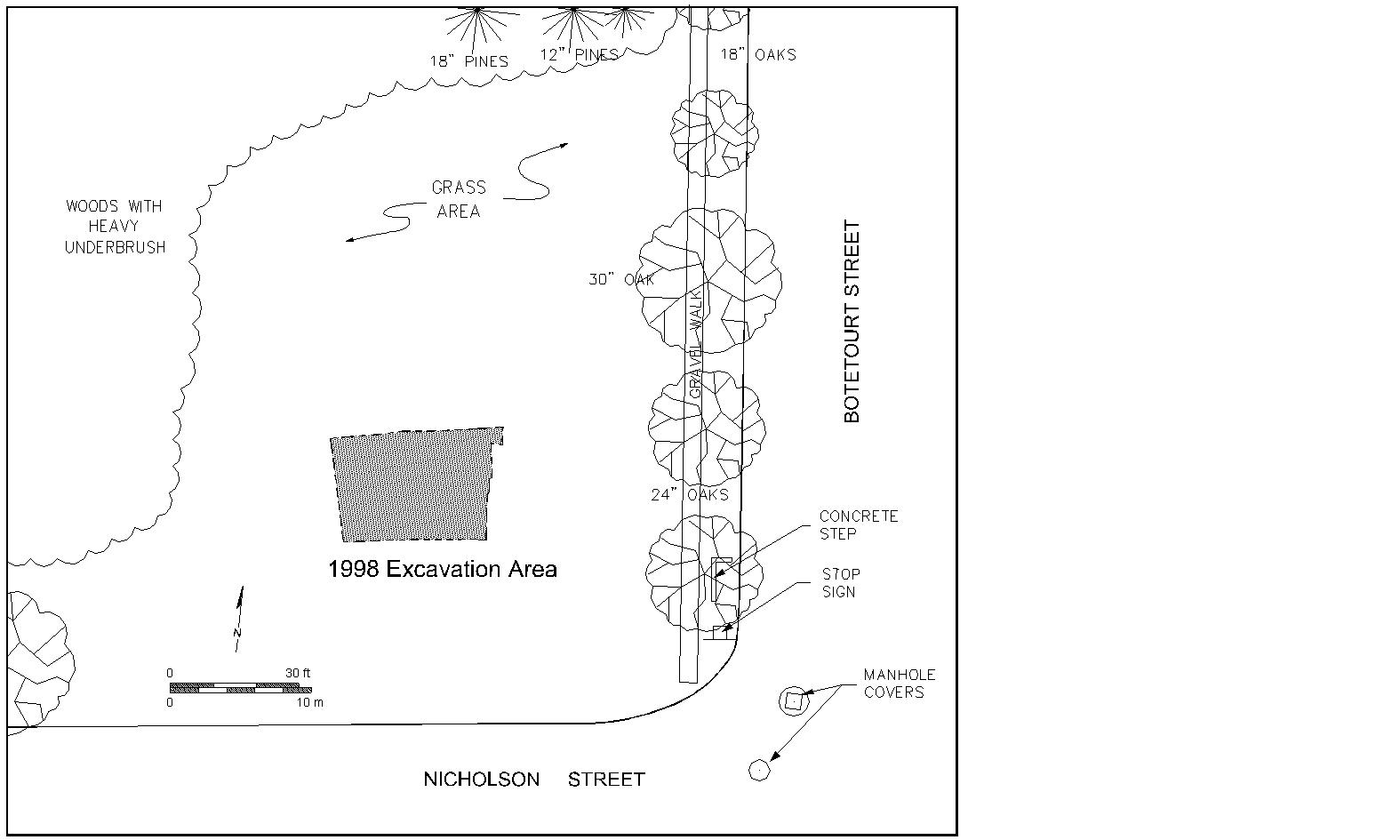

The excavation consisted of mechanical removal of the disturbed soil within the impact area of the proposed structure, and careful recording and excavation by hand of the intact archaeological features that lay below (Figure 2). The results of this investigation were significant. Perhaps most interesting was the rediscovery of a brick foundation and cellar that had been constructed within a ravine during the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century. Associated with this structure was a thick refuse deposit that was sealed with a clay cap in the first quarter of the eighteenth century. Many artifacts were recovered from this refuse, which provided information as to the date the building was constructed and the materials in use immediately after this construction. Also discovered were the remains of two possibly structural eighteenth-century posts and a narrow, Middle Plantation-era boundary ditch. This report will serve to explore the significance of these finds.

Further research is recommended for colonial lot 267, which contains the Ravenscroft site, and colonial lot 268, the site of a large, winged, domestic colonial structure. The Ravenscroft site (lot 267) contains an architecturally unique structure built in the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century and intact archaeological features with artifacts from that period. This building remained in use during the first five or six decades after Williamsburg was founded and retains information regarding this formative period. The domestic site on colonial lot 268 was built in the early eighteenth century and remained a part of Williamsburg until 1898, spanning crucial periods of town and national development. This site also contains intact foundations and archaeological features.

Acknowledgments

The successful completion of this project is largely due to the many contributions of the following people. Marley R. Brown III, Director of the Department of Archaeological Research, and David Muraca, Staff Archaeologist, provided guidance and encouragement throughout the entire project. Mark R. Wenger, Carl Lounsbury, William Graham, and Ed Chappell provided insight into the architectural interpretation of the site. Susan Christie and Bill Pittman conducted the artifact analysis, and the fragile artifacts were conserved by Emily Williams. Heather Harvey produced the graphics for this report and Greg Brown provided editing assistance. Finally, I would like to thank the efforts those who assisted in the field, including Mary Catherine Garden, who volunteered her weekend to this project, and the dedicated field crew, Josh Beatty, Lily Richards, R. Grant Gilmore III, and Lucie Vinceguerra.

Table of Contents

| Page | |

| Management Summary | i |

| Acknowledgments | ii |

| List of Figures | iv |

| List of Tables | iv |

| Chapter I: Background Information | 1 |

| Historical Context | 1 |

| Initial Settlement and the Middle Plantation Period | 1 |

| The Capital Era in Williamsburg | 3 |

| Previous Archaeological Research | 5 |

| Chapter II: Research Design and Methods | 7 |

| Research Goals | 7 |

| Field Methods | 7 |

| Laboratory Methods | 7 |

| Chapter III: Research Results | 9 |

| Stratigraphy Description | 9 |

| Feature Description | 9 |

| Modern Activity | 9 |

| Postholes | 10 |

| Grey Midden and Clay Cap | 11 |

| Colonial Structures | 14 |

| Ravine | 16 |

| Middle Plantation Boundary Ditch | 17 |

| Chapter IV: Discussion | 19 |

| Chapter V: Research Summary and Recommendations | 24 |

| References Cited | 25 |

| Page | |

| 1. General project area | 1 |

| 2. Closeup of project area | 2 |

| 3. Plan view of James River tributaries | 2 |

| 4. Plan view of colonial lots | 4 |

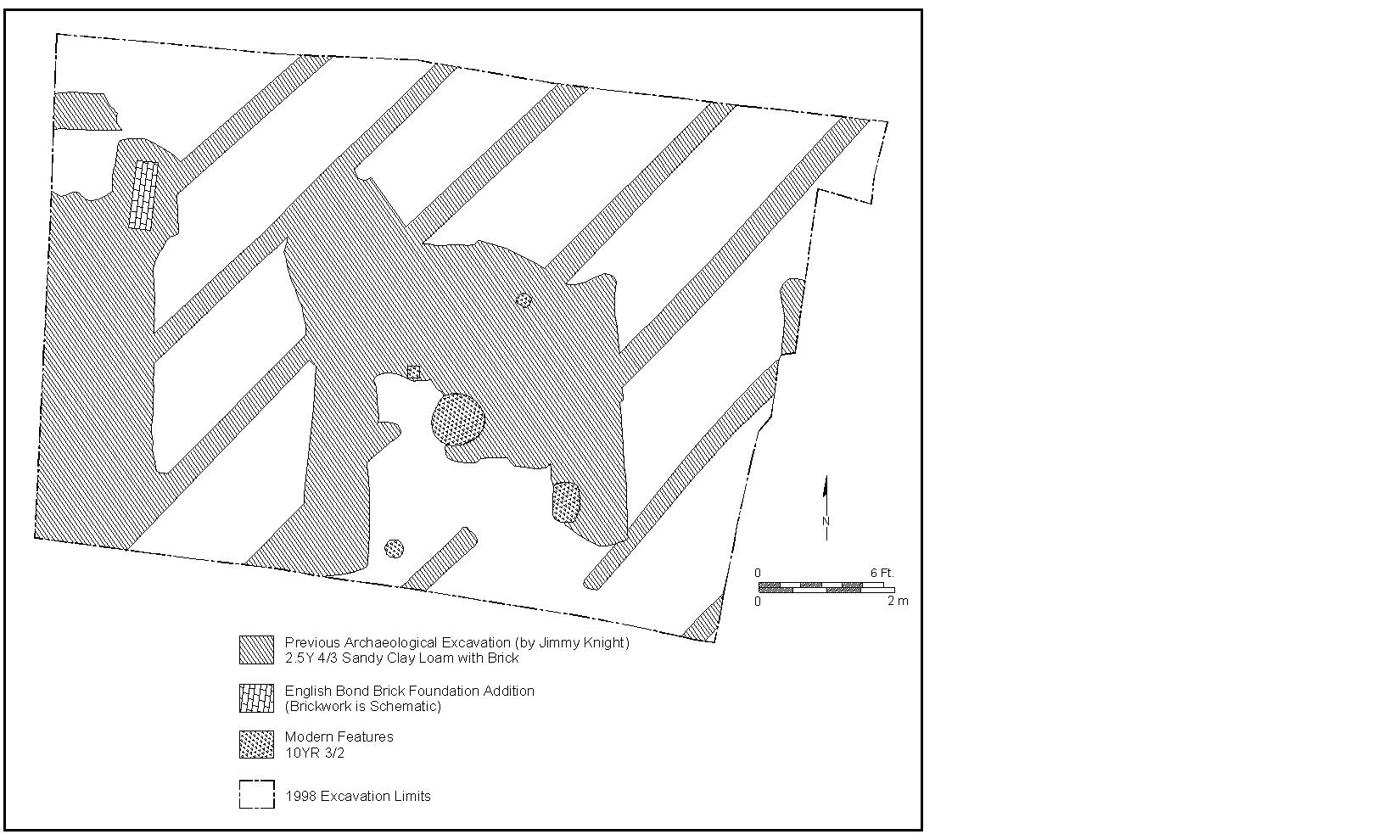

| 5. Plan view of modern activity | 9 |

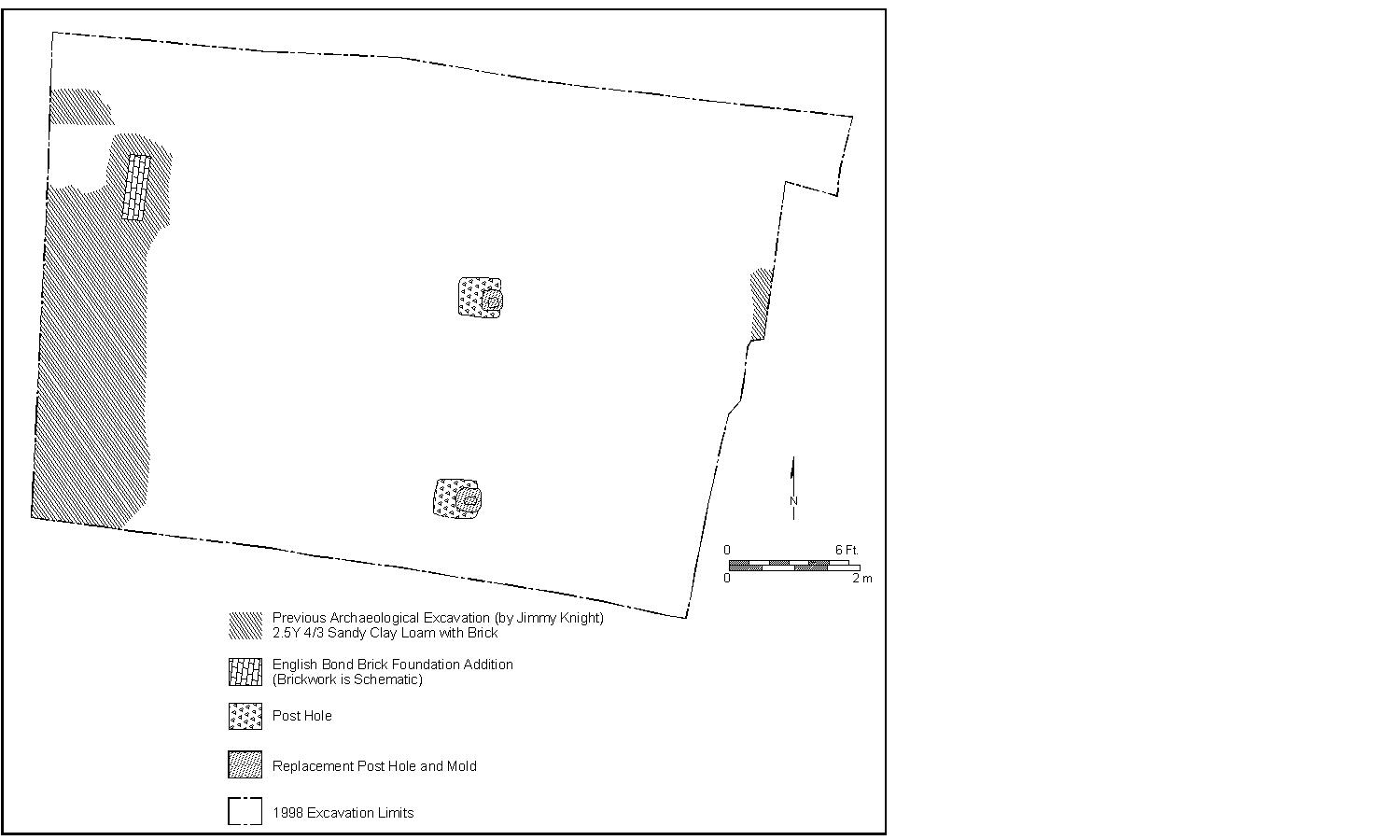

| 6. Plan view of postholes | 10 |

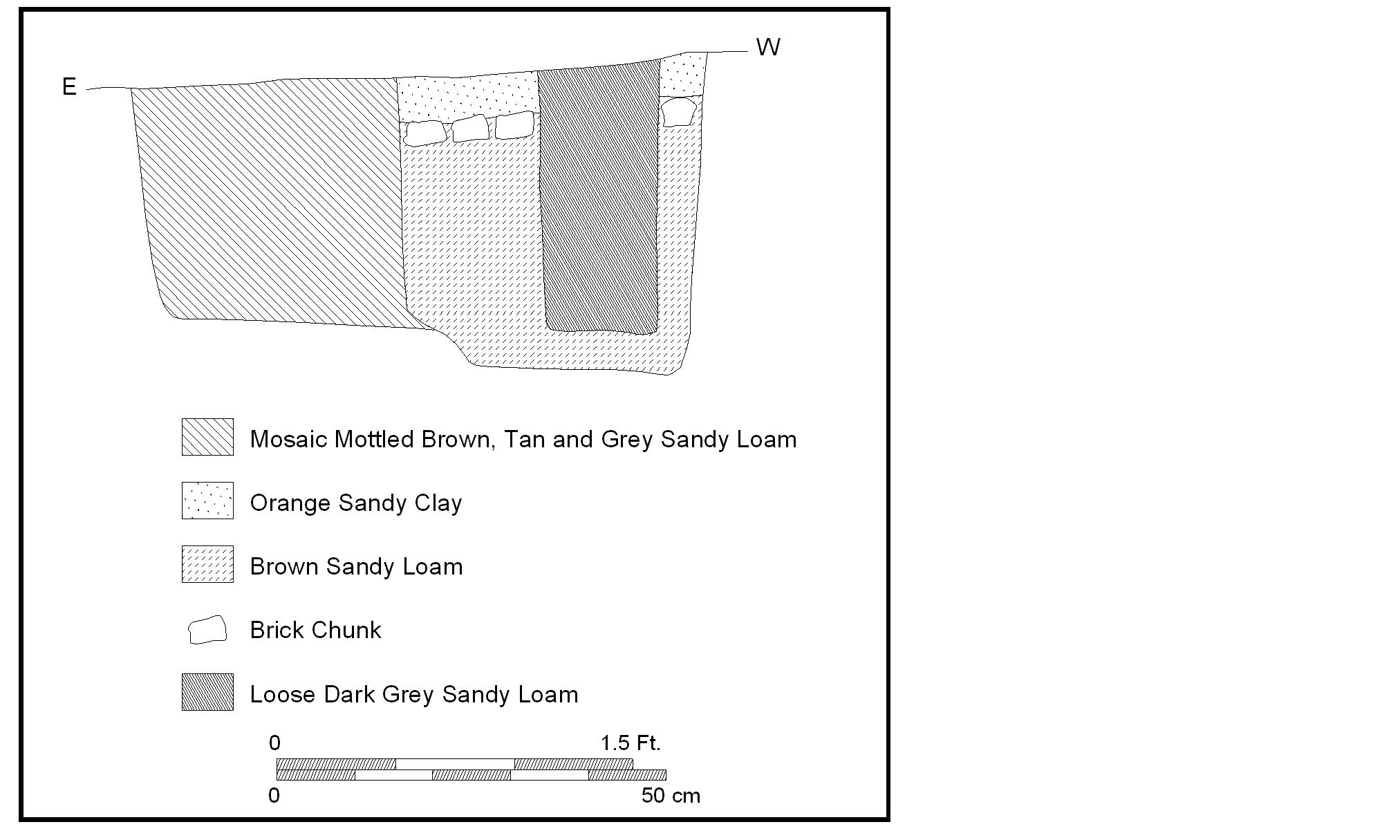

| 7. South wall profile of posthole | 11 |

| 8. Plan view of midden | 11 |

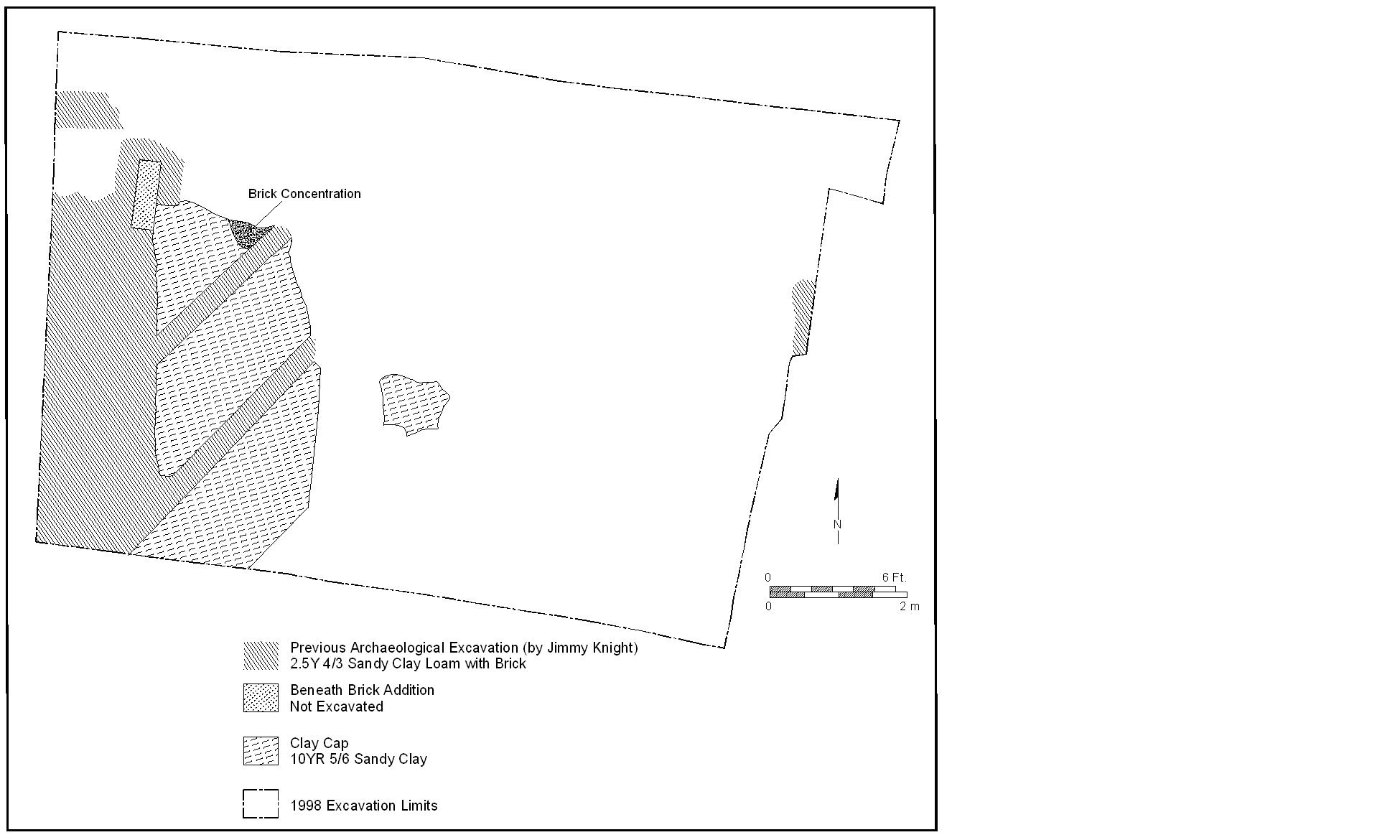

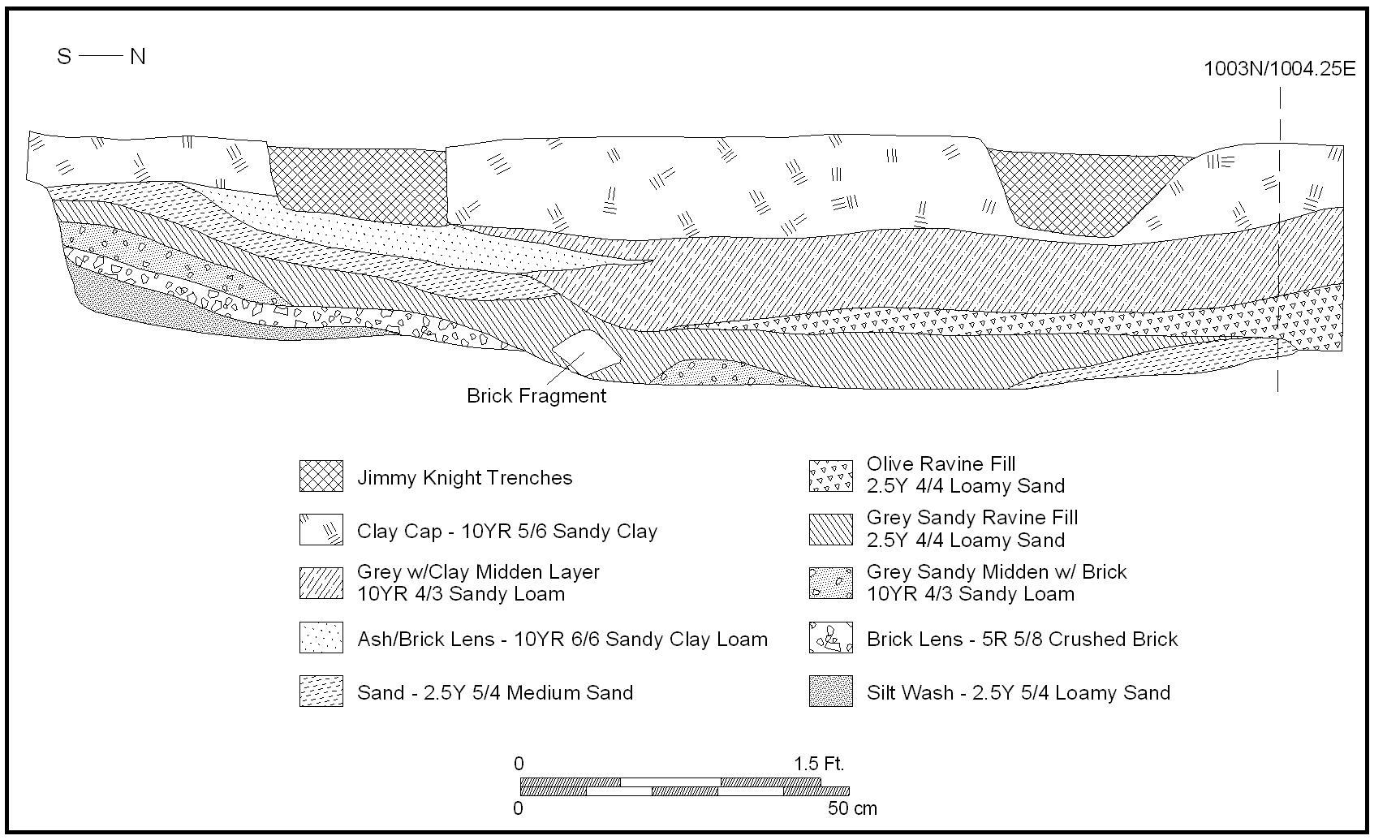

| 9. West wall profile of midden | 12 |

| 10. Wine bottle seals recovered from the midden | 13 |

| 11. Plan view of foundations on colonial lots 267 and 268 | 14 |

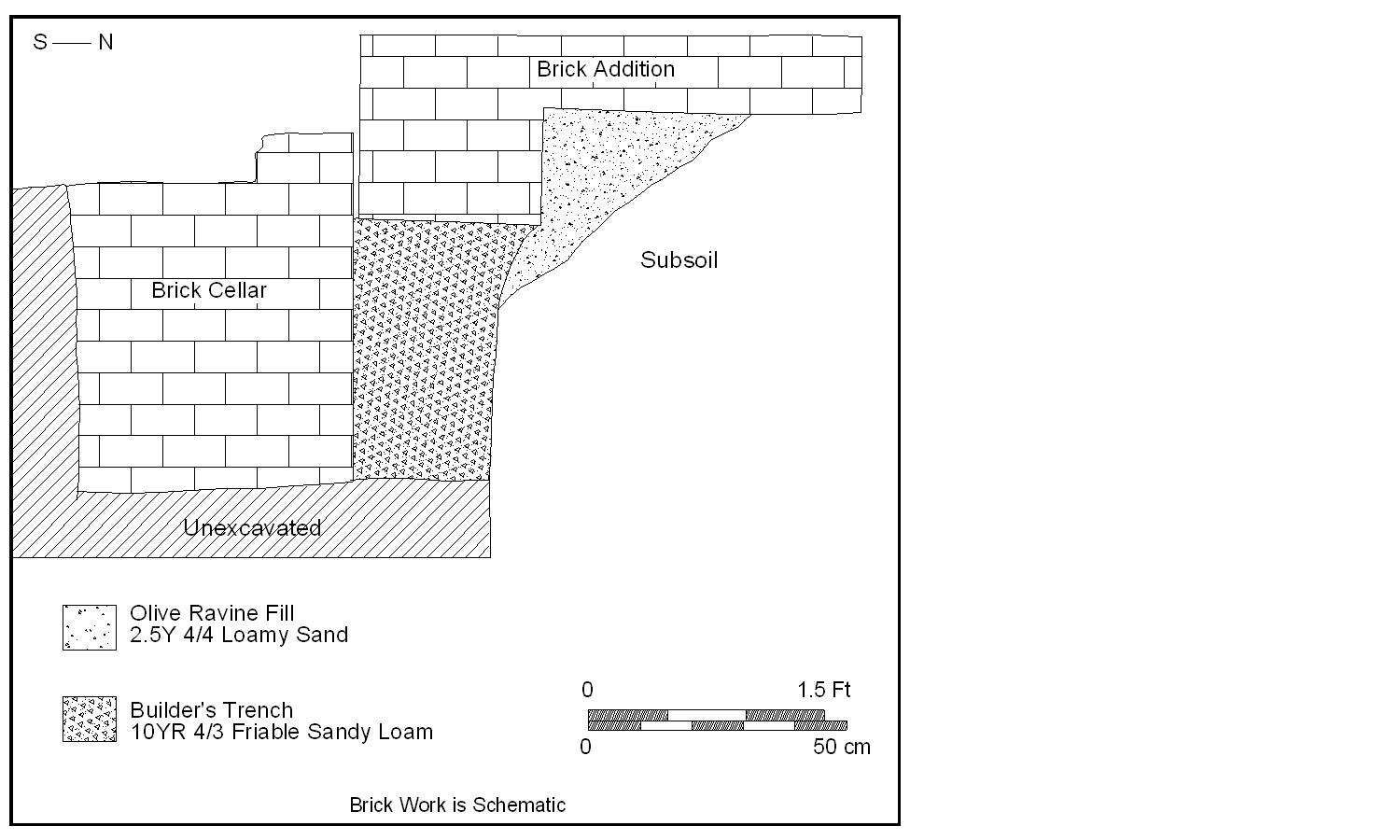

| 12. West wall profile of addition on colonial lot 267 | 15 |

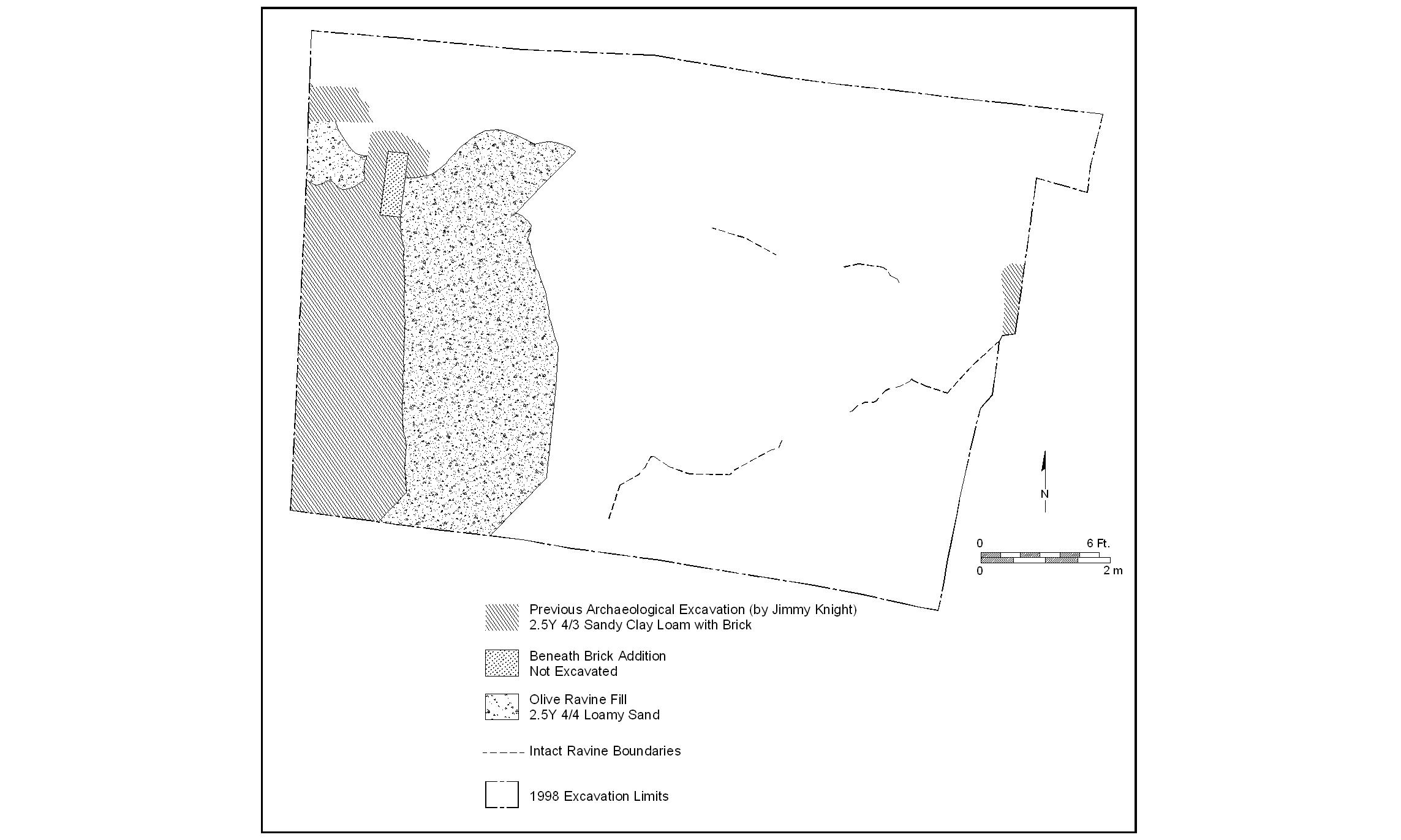

| 13. Plan view of ravine fill with intact ravine boundaries | 16 |

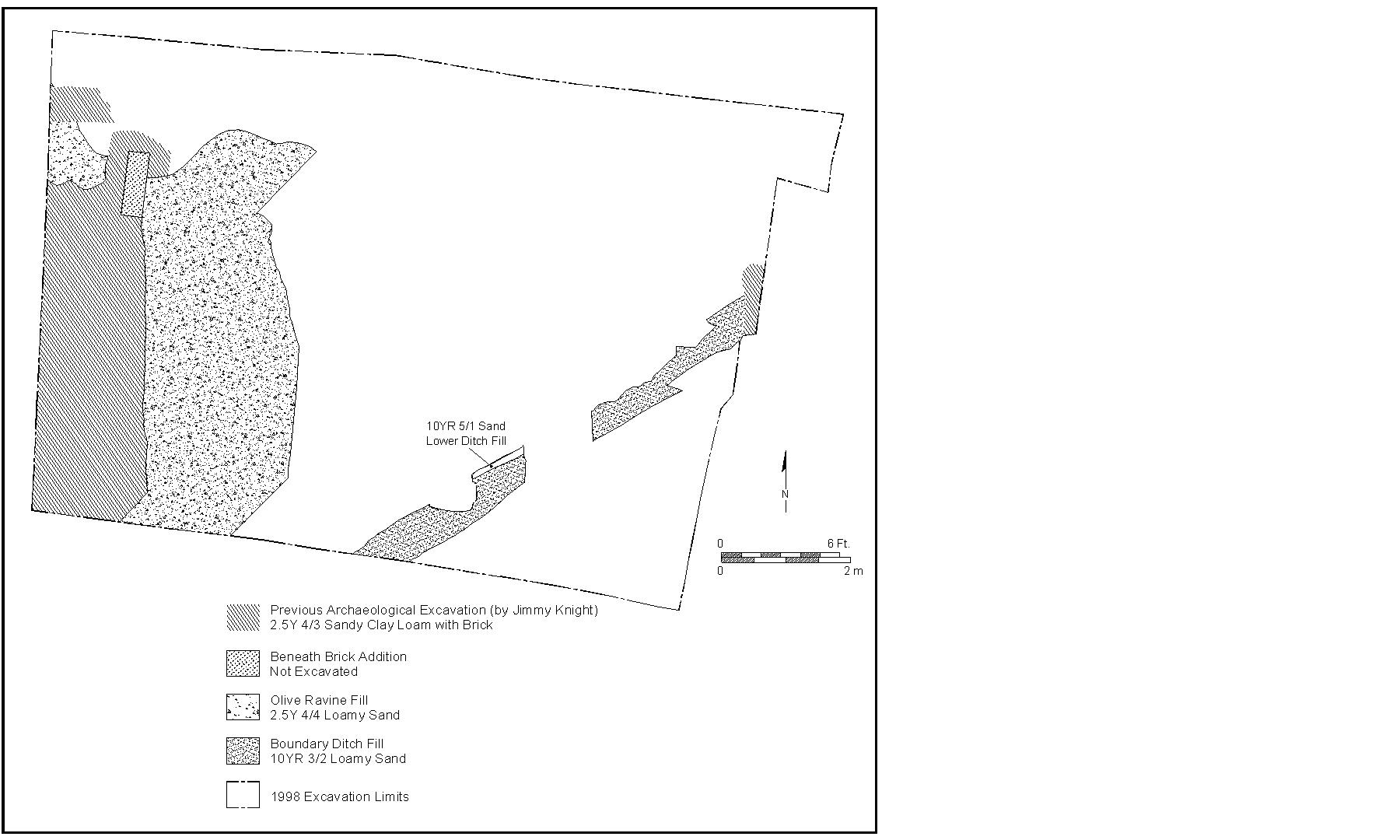

| 14. Plan view of Middle Plantation boundary ditch | 17 |

| Page | |

| 1. Comparison of Artifact Categories | 22 |

| 2. Rank Order of Compared Sites | 22 |

Chapter I:

Background Information

Historical Context

Initial Settlement and the Middle Plantation Period

The project area (Figures 1 and 2) is located within the area of initial expansion during the British colonial period in Virginia . In the seventeenth century, this area was known as Middle Plantation, and the project area itself was owned by one of the wealthiest men of the colony during that time, John Page.

In 1607, the Virginia Company of London established the first permanent English settlement in North America at Jamestown. The colonists' arrival was motivated by hopes of economic success and a desire to transform the wild into the civilized (Muraca 1994). From 1607 to 1632, English settlement clustered along the James River and the mouths of its tributaries. Fortified dwellings were lightly dispersed across the interior. As the settlement expanded, contact and conflict arose between the colonists and the Native Virginians. In 1622, conflict escalated to war. This war involved an initial attack by the Powhatans, followed by bloody insurgencies by the colonists (Morgan 1975).

Figure 1. General project area.

Figure 1. General project area.

Figure 2. Closeup of project area.

Figure 2. Closeup of project area.

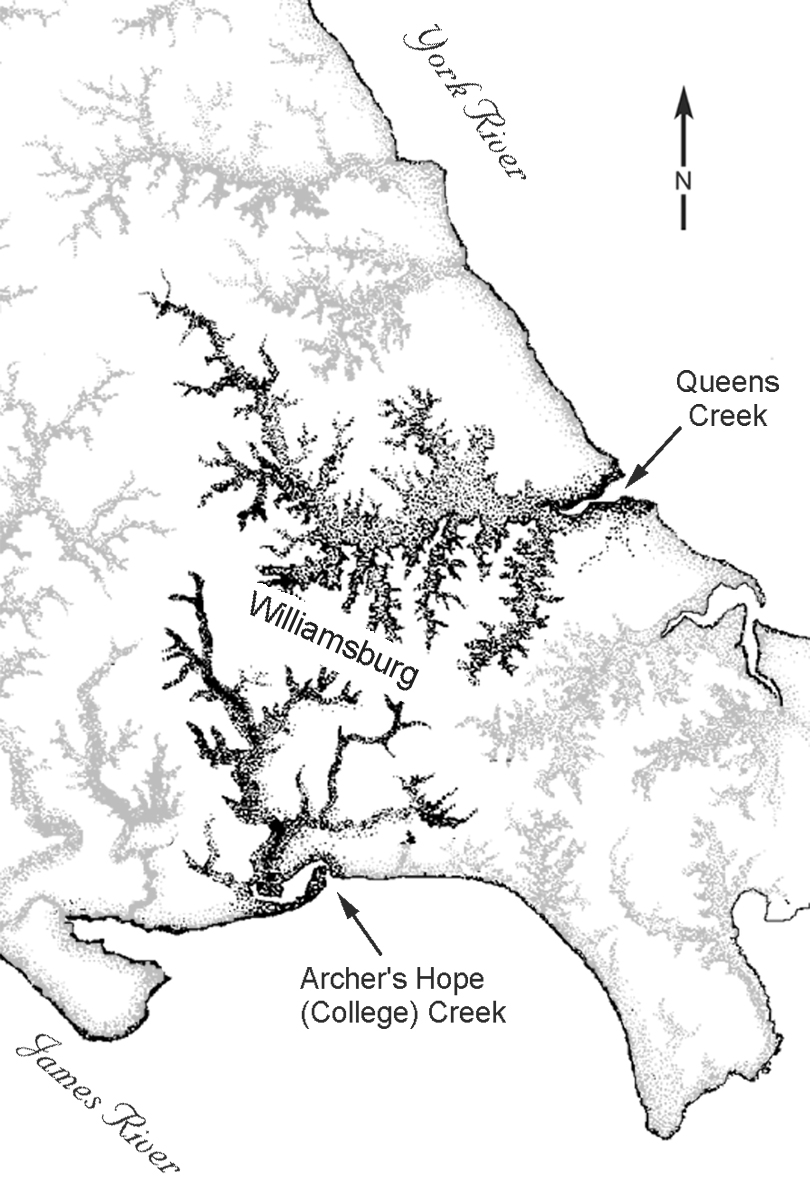

The colonists were aware that without interior expansion, their settlement would not prosper economically (Metz et. al 1998). In 1632/3 an Act of Assembly was created to establish Middle Plantation, the first major inland settlement. This settlement was bounded with a palisade, which stretched six miles from the mouth of College Creek, a James River tributary, to Queens Creek, a York River tributary (Figure 3). Middle Plantation, it was hoped, would secure the inland for colonial expansion and agricultural investments, and protect the area known as the Peninsula from Native American invasion.

Settlement of Middle Plantation began slowly, but steadily increased throughout the seventeenth century. Initially the colonists clustered along navigable waterways, such as Archer's Hope Creek near Jamestown, and Queens Creek farther inland. Wealthier landowners from Jamestown tended to establish plantations, manned by indentured servants, in the Archer's Hope area, while several smaller farmsteads existed near Queens Creek (Muraca 1994). Prominent landowners in the early period of Middle Plantation included John Potts, Francis Potts, George Menifee, and Secretary of the Colony Richard Kemp.

Figure 3. Plan view of James River tributaries.

Figure 3. Plan view of James River tributaries.

Middle Plantation began a more rapid period of growth in the mid-seventeenth century. The English Civil War had resulted in an increase in migration to the colonies by wealthy members of the gentry who had been loyal to the crown. Many of these new members of Virginia saw investment opportunities in Middle Plantation, where they could purchase land and establish agricultural plantations. Prominent government officials who resided in Middle Plantation included Thomas and Phillip Ludwell, Thomas Ballard, and John Page. Page eventually became one of Middle Plantation's largest landholders, with 350 acres including the project area. Page also acquired over 3000 acres across the York in New Kent County.

Towards the end of the seventeenth century, government officials decided to move their colonial capital to Middle Plantation, where they planned to establish a formal town to be known as Williamsburg. John and Francis Page owned much of the property selected for the development of the new capital town. Several Page buildings had to be demolished as the new roads and buildings were constructed. On April 27, 1705, the burgesses requested that a Page house standing on Duke of Gloucester Street be torn down "that the prospect of the Street between the Capitol and the Colledge may be cleer and that you take care to pay what you shall judge those houses to be worth" (McIlwaine 1910:4:55) . On May 5 of that year, the Burgesses paid the Page estate 3 pounds to demolish the "four old Houses and Oven" (McIlwaine 1910:4:69) , a very low price considering that these were noted to contain brick. Some Middle Plantation buildings that did not disrupt the new town plan were incorporated into the town, such as the structure known as the Jones Cellar near the Public Hospital which stood until the 1760s, for example. In 1699, the year the new capital was established, an observer described Middle Plantation: "Here are great helps and advances made already towards the beginning of a Town, a Church, an ordinary, several stores, two Mills, a smiths shop, a Grammar school, and above all the Colledge" (Anonymous 1699) .

The Capital Era in Williamsburg

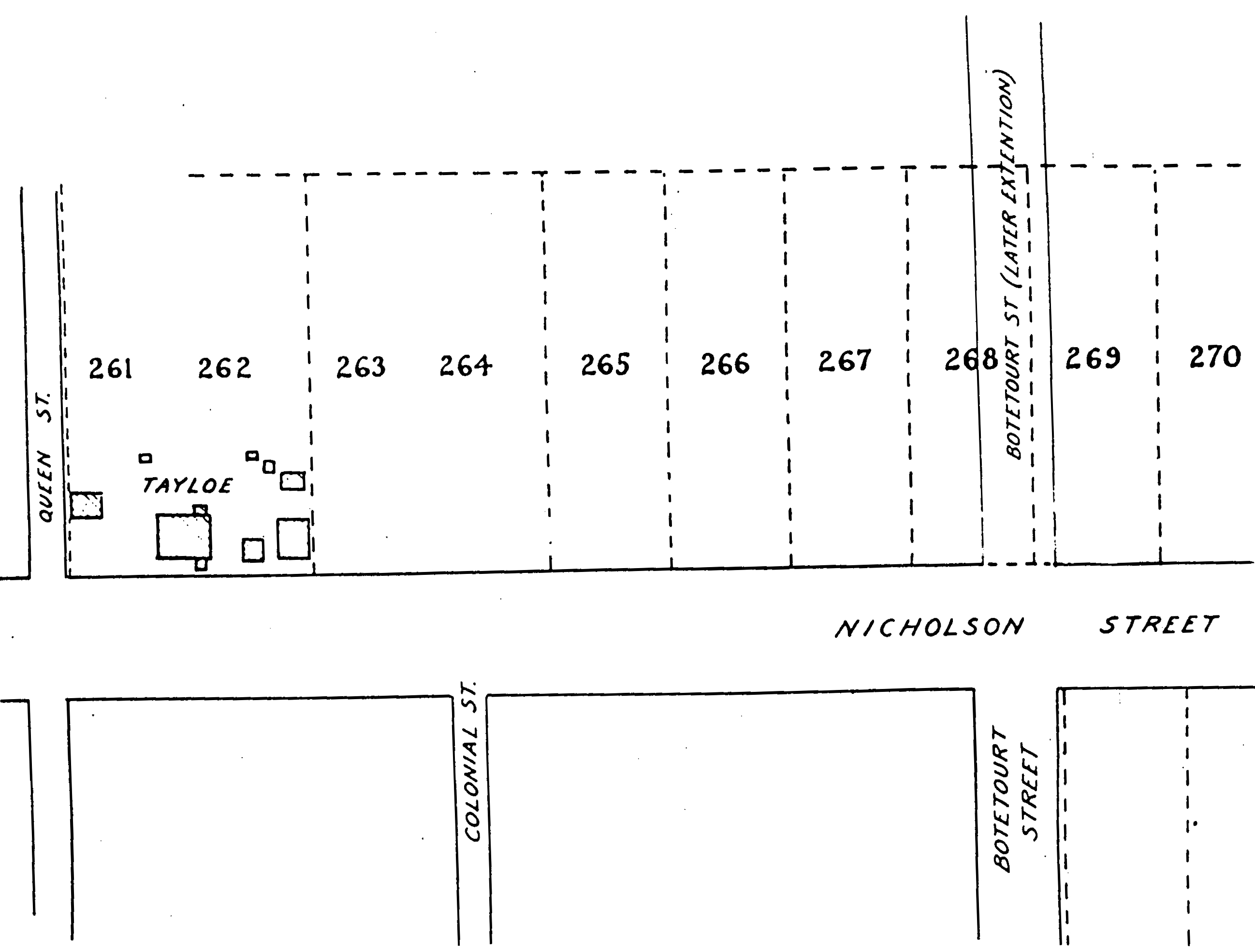

In the beginning of the eighteenth century, the Trustees of the Town of Williamsburg purchased property from the John Page estate, including the excavation area. The establishment of Williamsburg involved the division of property into half-acre lots. These lots were established along a grid bisected by a one mile-long street that stretched east from the College of William and Mary to the new Capitol building (Figure 4).

The excavation area straddles colonial lots 267 and 268. In 1713/14, Christopher Jackson purchased these two lots from the Trustees of Williamsburg. Jackson paid 4 pounds 15 shillings for these two lots plus four other lots—172, 271, 12, 43—also purchased at the same time. In accordance with common practice, the Trustees specified that Jackson must build a structure of specific size and materials on each lot within 24 months, or else the undeveloped lot would revert back to the Trustees as if the sale had never been made.

In 1715, Jackson sold lot 268, with "all houses, buildings, orchards" (Stephenson 1954:4)

to Thomas Ravenscroft for the price of seven pounds. This transaction did not include the neighboring lot 267. It is not known if Jackson built and resided on lot 267, if he built and

4

Figure 4. Plan view of colonial lots. (from Stephenson 1954.)

sold the lot, or if he did not build and the lot reverted back to the trustees. It is also possible that a building not mentioned in the deed already existed on the lot. The original price that Jackson paid the trustees was not elevated to include any pre-existing structures; however, documents relating to the sale of Middle Plantation structures reveal that the older buildings with brick foundations had been fairly appraised at less than one pound (McIlwaine 1910:4:69). Therefore, if a building had existed on lot 267 at the time of Jackson's purchase it would have had very little value.

Figure 4. Plan view of colonial lots. (from Stephenson 1954.)

sold the lot, or if he did not build and the lot reverted back to the trustees. It is also possible that a building not mentioned in the deed already existed on the lot. The original price that Jackson paid the trustees was not elevated to include any pre-existing structures; however, documents relating to the sale of Middle Plantation structures reveal that the older buildings with brick foundations had been fairly appraised at less than one pound (McIlwaine 1910:4:69). Therefore, if a building had existed on lot 267 at the time of Jackson's purchase it would have had very little value.

Apparently, Jackson did allow at least two of the lots purchased in 1713/14, lots 172 and 43, to revert back to the trustees. These two lots were sold in 1716 and 1718 respectively, by the trustees to other individuals, again with the requirement that a building suiting the specifications be constructed on the lots. There is no information regarding what became of lot 267 immediately after Jackson purchased it.

In 1739, a reference to this lot was made in a mortgage transacted eight years earlier by Dudley Digges to Robert Wills (Stephenson 1954). This document mentioned three lots adjacent to Davenport's property (Davenport possessed lots 269 and 270) that Digges had recently acquired from Ravenscroft, probably 266, 267 and 268. There is no information regarding when nor from whom Ravenscroft had purchased the two other lots. In 1731, the same year the mortgage was enacted, Wills petitioned the court of York County to grant him license to operate an ordinary at his home. This license was granted. Wills may have been residing on Digges's property at that time. In 1739, Digges disregarded the mortgage payments and Wills foreclosed on the property. At the time of the foreclosure, the property value was 91 pounds 15 shillings. This marked a great increase from the seven pounds that Ravenscroft initially paid for lot 268, indicating that improvements had been made to the property during this time (Stephenson 1954).

5In July 1739, Wills conveyed the three lots to Thomas Nelson for 100 pounds. Nelson died in 1745 and, according to his will, left his real estate to his son William. Later that same year, William Nelson leased lots 266, 267, 268 and 700 to John Holt (lot 700 has not been located on any historical maps). Four lots were now included in the transaction, again with no indication of how the fourth lot was acquired. Holt apparently ran into financial difficulties, for in 1753 he mortgaged the lots to Peyton Randolph and eventually left the colony bankrupt. In 1754, the remaining time from Holt's lease was granted to William Hunter (Stephenson 1954).

In 1763, Nelson granted a new lease to Joseph Royle. Three years later, Royle died and left the property to his son William. William Royle, evidently now the owner of the property, offered it for sale in 1785. A map dated 1791 indicated that "Jackson," possibly George B. Jackson, owned lots 266, 267 and 268 (Stephenson 1954). In 1826, Robert McCandlish possessed the property. McCandlish's carpenter, Richard Brooker, wrote an account of some repairs he had performed on the property. In this account he described an area of McCandlish's holdings as "the old bake house lot" that may have been lot 267 (Stephenson 1954: 15).

McCandlish held the property until 1865, when William Vest acquired the lots. Twenty-two years later Vest sold the lots, together with his other holdings on the Tayloe property, to M. R. Harrell. The dwelling on Harrell's property, on lot 268, had probably been in existence since the Ravenscroft period of 1715-1731, with structural additions added over time. In 1896, during Harrell's tenure, a large fire inflamed an entire block on Duke of Gloucester Street between Colonial and Botetourt Streets. This fire completely destroyed the Harrell buildings. In 1928, a resident of Williamsburg named Mr. Charles remembered the Harrell residence as "a long and very old one and a half story frame building with dormer windows" (Stephenson 1954:17) . Another resident of Williamsburg, Mrs. Victoria Lee, described this house with the following words:

This place had an unusual hall. There were two corner fireplaces, diagonally across from one another, in this hall; and it had also a very fine stairway. This was a two story house, which was occupied after the war, by negroes who were living there when the house burned fifty years ago(Stephenson 1954:18).

After this disaster the empty lots were conveyed to Eugene Potts in 1904, to Joanne Harris in 1905, and to Arthur Harris in 1906. The Williamsburg School Board acquired the property in 1907, and sold it in 1939 to Williamsburg Restoration, Incorporated (Stephenson 1954). These lots remain in the possession of the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation at present.

Previous Archaeological Research

In 1954, colonial lots 267 and 268 were investigated for archaeological remains by J.M. Knight, an architect and archaeologist for the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation. Knight excavated diagonal trenches across both lots and located the remains of two colonial structures, one located on lot 267 and the other located on lot 268. The latter extended beneath Botetourt Street (see Figures 11 and 12).

6The foundation uncovered on lot 267 measured 14 feet by 16 feet and contained a brick cellar with a corner fireplace and a bulkhead entrance that faced Nicholson Street. Knight believed that this foundation was constructed in the early eighteenth century (Noël Hume 1962). Excavation of this building included complete removal of the fill within the cellar and partial excavation around the exterior of the foundation. Knight collected several artifacts from the cellar fill. The specific provenience of the artifacts within the cellar was not documented; however, a report compiled in 1959 and 1962 by archaeology student Robert M. Barrow and archaeologist Audrey Noël Hume provided a description of the artifacts. These artifacts are now stored at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Archaeological Research.

The finds from this excavation included ceramics, glass, small finds, iron objects and architectural material. The ceramics were comprised of domestic tableware and coarseware, such as German, English and American stoneware, slipware, tin enameled ware, creamware, pearleware, redware and locally-made hand-built pottery. Glass finds included leaded tableware, pharmaceutical and beverage bottles, and a glass bird feeder. Other household items recovered were fragments of cutlery, candlesticks, clay pipes, iron furniture hardware and architectural hardware, and seventeen fragments of ceramic roofing tiles (Noël Hume and Barrow 1962). This building was documented through scaled drawings and photographs.

The remains of the structure on lot 268 measured 50 feet by 24 feet with a small west wing. A kitchen or office building lay directly west of the wing and measured 14 feet by 16 feet. The west structure was entirely excavated, and the main structure was exposed up to its intersection with Botetourt Street. The main structure, which contained a cellar, was built in the eighteenth century, possibly during the Ravenscroft period of 1715-1739 (Stephenson 1954). In 1782, the larger building was depicted on the Frenchman's map. This structure stood until 1896, at which time it was destroyed by fire. Knight documented the structures with scaled drawings and photographs.

Lots 267 and 268 were recently re-investigated by Colonial Williamsburg Foundation's Department of Archaeological Research. During December 1997, archaeologists performed limited testing of an area on the lots which had been designated to contain the tenant house exhibit. This testing consisted of the excavation of nine 75x75 cm units placed at ten-meter intervals across the site. Within these units, over two thousand artifacts were recovered and two features were revealed that were possibly the remains of seventeenth- or eighteenth-century activities. Historical research indicated that these lots were occupied throughout the eighteenth century. As a result of the historical and archaeological investigation, a full-scale excavation was recommended for the area to be impacted by the placement of the museum exhibit. This report concerns the archaeology performed in compliance with those recommendations.

Chapter II:

Research Design and Methods

Research Goals

The archaeological investigation of colonial lot 267 and 268 was designed to record and remove all intact archaeological remains which may be impacted by the proposed tenant house exhibit. Excavation of the approximately 7x10 meter area designated for placement of the exhibit included mechanical stripping of the plowzone and careful recording and excavation by hand of the archaeological features which lay beneath.

Field Methods

Excavation techniques involved systematic documentation and removal of the cultural features that lay within the impact area. The area had recently been under cultivation, and plowing had disturbed the first 24 to 40 centimeters of soil. This disturbed layer was removed mechanically with a backhoe. At the level of undisturbed soil, or subsoil, the surface was carefully cleaned by hand to reveal any intact cultural remains or features. In order to maintain spatial control of the site, a grid was placed at one-meter intervals across the area aligned with the town grid. These grid squares were numbered in correspondence with the north and east coordinates of the northwest corner of each square. For a finer level of description, individual numbers, or context numbers, were also given for each separate soil layer and soil removal or filling episode within the site.

The soil was excavated using shovels and trowels. Except for the disturbed plowzone layer and other recently disturbed features on the site, all soil was sifted through ¼-inch screen. Artifacts encountered in the screens were saved. The presence of artifacts that were not saved, such as brick, mortar, oyster shell and charcoal, were noted on the forms for each specific soil layer. The artifacts recovered were bagged according to the exact square and soil layer from which they were retrieved.

The soil layers were removed by natural boundaries; by this method, changes in the soil color, consistency or inclusions were carefully observed for indications of a new soil layer. Excavation techniques and soil characteristics were recorded for each context on a Context Record Form. Maps were drawn to record the plan and profile view for each seventeenth- or eighteenth-century cultural feature. Photographs were also taken to document some of the features. When the excavation was finished, the site was covered with sand and prepared for the placement of the reconstructed tenant house.

Laboratory Methods

The artifacts recovered during this excavation were washed and sorted. An artifact inventory was created using a computerized coding system known as Re:discovery. Conservation was performed on glass wine bottle seals, lead window casings and other fragile metal 8 objects. Dating evidence was obtained from the earliest manufacturing date for the latest artifact deposited in each layer. This information provided a terminus post quem (T.P.Q.) which represented the date after which the artifacts within each layer must have been deposited. The artifacts were placed in acid-free polyethylene bags for storage at the Department of Archaeological Research.

The artifact analysis, including the various uses, prices, manufacturing techniques and manufacturing dates for the objects, were incorporated with the field data to constitute the basis for the research results.

Chapter III:

Research Results

Stratigraphy Description

Colonial lot 267 and 268 were investigated by mechanical removal of the disturbed plowzone across an approximately 7 meter by 10 meter area, followed by careful recording and removal of all cultural features at the undisturbed subsoil level. The location of previously excavated areas was clearly visible. Five individual contexts were assigned to this recent disturbance.

Fifty individual contexts were assigned to undisturbed soil deposits from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These deposits were grouped into four master contexts, representing major episodes that occurred on this site during the Middle Plantation and early Williamsburg periods. These episodes included a pair of possibly structural postholes, a large trash deposit within a ravine, a late seventeenth- or early eighteenth-century brick foundation with later addition, and a Middle Plantation-era boundary ditch.

Feature Description

Modern Activity

In 1954, J.M. Knight uncovered the remains of two brick foundations—one located on lot 267, and the other located on lot 268 extending beneath Botetourt Street (Stephenson 1954). This excavation consisted of the placement of linear cross-trenches about 30 centimeters wide placed roughly 85 centimeters apart over the three lots, as well as the excavation of larger areas opened up around and within the brick foundations. The remains of these trenches and the larger excavations were clearly visible (Figure 5). There was also evidence of a larger disturbance between the two structures which postdated the trenching but may have also resulted from the archaeological investigation by Knight.

These disturbances had been backfilled with dark brown sandy loam containing heavy inclusions of brick rubble and artifacts from the seventeenth to twentieth centuries. Some of this disturbance had impacted

10

Figure 5. Plan view of modern activity.

the archaeological resources on the site. The disturbed soil was removed from the site and, in certain areas, revealed intact seventeenth- and eighteenth-century stratigraphy beneath. None of the soil from the modern archaeological activity was screened.

Figure 5. Plan view of modern activity.

the archaeological resources on the site. The disturbed soil was removed from the site and, in certain areas, revealed intact seventeenth- and eighteenth-century stratigraphy beneath. None of the soil from the modern archaeological activity was screened.

Postholes

Two large postholes, with smaller replacement postholes within, were discovered in the excavation (Figure 6). These posts were three meters apart on a roughly north to south axis. They were positioned about 4.25 meters west of the large structural foundation on colonial lot 268, and about 5.40 meters east of the foundation and cellar on colonial lot 267. These posts were almost certainly in existence when the larger building on 268 was in use, and possibly in existence when the building on 267 was in use, though it is not known how or even if these posts related to either of the two buildings.

The lower and earlier postholes were 58 centimeters to 60 centimeters wide, and extended about 30 centimeters into the subsoil (Figure 7). The posthole fills consisted of brown sandy loam with flecks of brick, marl and charcoal throughout. There was no visible mold in these postholes, but the eastern half of both was cut by later replacement postholes, both of which contained post molds 10 by 13 centimeters in size. These later posts had been given extra support by filling the holes with clay and flat laid bricks.

The artifacts within the fill of the postholes, for both the larger, earlier holes and the smaller, later holes suggest that the posts were placed after 1720. Given that only two of the posts in this series were uncovered, it is difficult to assign a definite function to them. However,

Figure 6. Plan view of postholes.

11

Figure 6. Plan view of postholes.

11

Figure 7. South wall profile of posthole.

the size of the earlier posts, and the placement of the replacement posts in exactly the same location, suggest that these posts supported a heavy frame and that care was taken in their upkeep. Possibly, these were a pair of structural posts for a small earthfast structure or shed, although they may have also been used as fence posts.

Figure 7. South wall profile of posthole.

the size of the earlier posts, and the placement of the replacement posts in exactly the same location, suggest that these posts supported a heavy frame and that care was taken in their upkeep. Possibly, these were a pair of structural posts for a small earthfast structure or shed, although they may have also been used as fence posts.

Grey Midden and Clay Cap

One of the more intriguing features of this site was a layer of trash deposited within a ravine that ran westward across the excavation (Figure 8). The east edge of this deposit extended beyond the east edge of the excavation. On the west, this deposit abutted the brick foundation and cellar on colonial lot 267 and was contemporaneous with the early occupation of this structure. Sometime in the first two decades of the eighteenth century, this layer was sealed with a thick clay cap that isolated the deposit from later contamination. Unfortunately, a portion of this deposit had been impacted by the 1954 archaeological investigations.

Figure 8. Plan view of midden.

Figure 8. Plan view of midden.

The midden expanded 9.10 meters, and spanned the area between the eastern edge of the excavation and the brick foundation on lot 267. On the eastern edge, the deposit was only 1.5 meters wide and 0.23 meters deep. The layer quickly widened and deepened to the west and reached a width of 5.2 meters and depth of 1.0 meter where it abutted the brick cellar foundation. Directly beneath this layer lay the builder's trench for the cellar. Therefore, it was possible to conclude that the artifacts recovered from the midden were deposited soon after the structure had been built. The brick foundation had been constructed within a ravine, which may have resulted in water damage to the eastern cellar wall. Possibly in an effort to fill the ravine and halt this damage, the ravine was filled with trash and debris and sealed with a clay cap.

12 Figure 9. West wall profile of midden.

Figure 9. West wall profile of midden.

The soil in the midden contained pockets of ash, clay, heavy brick rubble, charcoal and shell, as well as over 9000 artifacts. The soil varied in color from brown to brownish yellow. The deposit was thickest at 30 centimeters thick along the northeast edge of the ravine by the foundation, suggesting that the deposition originated from this area. A clay cap measuring 34 centimeters thick sealed this trash layer. The clay was brownish yellow, redeposited subsoil clay that contained small brick flecks throughout. This clay was packed against the brick cellar foundation (Figure 9).

A large assemblage of late seventeenth- and early eighteenth-century artifacts were recovered from the ravine which can be associated with the occupation or use of the brick structure on colonial lot 267. These artifacts were identified, analyzed and described by Susan Christie. The most striking aspect of the midden assemblage was the very large amount of wine bottle glass recovered. Over 5700 fragments of wine bottle glass were found, comprising over 60% of the artifacts from the midden fill. The majority of the bottles were of the onion and mallet form manufactured during the late seventeenth to early eighteenth century. Rectangular case bottles also represented a small percentage of the bottles.

Six wine bottle seals were recovered (Figure 10). Four exhibited a crest displaying a coronet atop a coat of arms bearing a cross, supported on each side by standing dogs. Beneath the dogs was a scrolling banner bearing a motto in French, which on two seals read "MAINT…ARM…" and on one seal read "MAINT…DROIT." An association or date for these seals was not determined. The fifth seal depicted a baronial crown above a fox standing on a rouletted horizontal line representing earth. This seal could represent a more refined version of a ca. 1700 seal of the Peirpont family. The sixth seal was incomplete and bore a milled edge bordering a beaded coat of arms. Again, association and date for this seal has yet to be determined.

13 Figure 10. Wine bottle seals recovered from the midden. Drawn by H. Harvey.

Figure 10. Wine bottle seals recovered from the midden. Drawn by H. Harvey.

In addition to wine bottle glass, the midden fill contained a few fragments of clear, leaded glass. The forms represented a decanter, a continental oil bottle, scent bottles, tumblers, and stemmed wine glasses. Two datable stems included a Silesian style, manufactured between 1710 and 1730 (Noël Hume 1991:190), and a funnel shaped style with basal teardrop, a decorative technique that began in the fourth quarter of the seventeenth century.

The ceramics recovered from the midden fill were dominated by English delftware, but also contained fragments of white salt glazed stoneware, Yorktown courseware and Buckley coarseware, which provided the T.P.Q. of 1725. Earlier dated wares included Red Sandy Ware, Fulham, Westerwald and Nottingham stonewares, North Devon coarseware and Chinese porcelain. A few fragments of locally produced, hand-built pottery were also recovered. In addition, two unusual vessels came from the midden and have tentatively been identified. One appears to be a seventeenth-century French tin-enameled salt, and the other a white salt-glazed vessel with a cylindrical bucket shape and squared rim, which may have also been a salt.

Non-kitchen related ceramic items from the midden included two, and possibly three, crucibles and fragments of seventeenth-century clay roofing tiles. The latter, being a particularly important architectural feature of the nearby structure, will be discussed further in this report.

Other artifacts recovered included tobacco pipe fragments, one of which displayed the maker's mark of the Manby family dating to the last quarter of the seventeenth century. A very small percentage of the fragments were locally produced "Chesapeake" pipes. In addition, varieties of metal hardware were found in the midden, including iron handles, hooks, hinges, tongs, a file, and other various objects. Copper alloy materials and lead items were also present. These metals included the following notable items: a brass coin weight, a complete lead excise bale seal dating from the reign of Queen Anne (1702-1714), and several inscribed lead window casings indicating the date 1717.

Lastly, a large quantity of faunal remains was included in the fill of the midden. Bone comprised over 15% of the total artifacts from this feature. The various species represented 14 in the faunal collection has not been determined. However, a bear (Ursus americanus) tooth was observed in the collection, an unprecedented find for this period in Williamsburg (Bowen, personal communication). As this species had disappeared from the area by this time, its presence in the artifact collection from colonial lot 267 appears to be as an oddity brought in from the western part of the colony.

Colonial Structures

Previous archaeological investigations revealed two colonial structures within the vicinity of the excavation. One, on colonial lot 268, consisted of a large brick foundation with west wing and cellar (Figure 11). This structure was probably constructed during the 1715-1731 Ravenscroft ownership of the lot, with later additions. The western edge of the west wing was just beyond the eastern limits of the excavation. This structure was not investigated in the current excavation, nor were any features directly attributable to this structure encountered. It does appear that the building and related features remain intact outside the limits of the 1998 excavation.

On colonial lot 267, the southern half of another colonial structure had been previously identified and documented. The floor plan had at least two cells, with a later, brick addition extended off the northeast corner of the brick foundation. A brick-lined cellar was located beneath the southern room of the structure and was heated with a corner fireplace. The north cell area was not located in the 1954 excavations, nor was this area included in the current excavation, but its presence is indicated by the central, north-facing hearth constructed on the northern exterior of the cellar. Because Knight did not discover any brick remains of this cell during his excavation of the area, it is likely that the cell was founded

Figure 11. Plan view of foundations on colonial lots 267 and 268 (from Knight 1954).

15

upon perishable materials, such as wooden posts. The brick foundation was substantial, measuring one and a half bricks wide, with English bond and shell mortar. During the current excavation, the only portion of this structure revealed was a section of the later addition placed off the northeast corner of the original foundation (Figure 12). The grey midden layer and clay cap described above were associated with the early occupation of the building and overlay the builder's trench excavated during the construction of the cellar.

Figure 11. Plan view of foundations on colonial lots 267 and 268 (from Knight 1954).

15

upon perishable materials, such as wooden posts. The brick foundation was substantial, measuring one and a half bricks wide, with English bond and shell mortar. During the current excavation, the only portion of this structure revealed was a section of the later addition placed off the northeast corner of the original foundation (Figure 12). The grey midden layer and clay cap described above were associated with the early occupation of the building and overlay the builder's trench excavated during the construction of the cellar.

The overall architectural style of the lot 267 structure was unique to Williamsburg. The narrow side of the building, with the cellar entrance in the center of the south wall, faced onto Nicholson Street. Yet to orient this building along the town grid, the entrance would also have been on this narrow south wall, probably through a narrow passage east of the central cellar steps. This front passage entry style has not yet been observed in Williamsburg, though this type of entrance can be found in England in seventeenth- and eighteenth-century urban contexts. There, two-celled structures with central hearths were entered through a narrow front passage extending along one side of the length of the building. These house plans were used in urban areas to maximize the space and accommodate more buildings along the street (Wenger and Graham, personal communication). Often, the front room of this type of building was referred to as a "shop" on historical plans. The meaning of this word at that time period is ambiguous, but could indicate a merchant-style setting. This urban construction style has also been found at Jamestown. However, the use of the front side passage was not previously known in Williamsburg. Here, buildings faced directly onto the street from either the long or narrow side of the structure. No narrow-end house fronts are known to have had central cellar entrances. It is also possible that the building had a direct entry into the north or east wall, but in these cases the building would not have been oriented towards Nicholson Street, indicating that the structure predated the street.

Figure 12. West wall profile of addition on colonial lot 267.

Figure 12. West wall profile of addition on colonial lot 267.

Another unique feature of this building was its nonconformity with Williamsburg's building codes. The city of Williamsburg was rigidly planned. Its structures were aligned along a grid system bisected by Duke of Gloucester Street, stretching east from the College of William and Mary to the Capitol. As the trustees of the city sold lots along Duke of Gloucester Street, they included in each deed a list of building requirements. For the back streets these requirements did not apply unless the property developers specified that these requirements be enacted in the deed of sale. In 1713/14, when Jackson purchased lots 267 and 268, the specifications were applied. However, the structure uncovered on lot 267 did not meet these specifications. Brick foundations supported only the southern half of the building, while posts may have supported the northern half, which would have been prone to deterioration. This indicates that either the building requirements were not rigidly enforced on the back streets, or that the structure was built before the requirements had been put into effect.

The artifacts recovered from the grey midden layer that postdated the building have also yielded some clues about the architectural components of this structure. These items include window glass, lead window casing, nails, dressed slate, whitewashed plaster, and ceramic roofing tiles.

The destruction of the building probably occurred in the first quarter of the nineteenth century. This can be discerned from the artifact collection excavated in 1954 from the fill of the cellar. These artifacts were likely deposited after the standing structure had fallen into ruin. Open cellars were often used for trash disposal, thus the artifacts may have come from the ruin itself, or brought to the cellar from a nearby household. Most of the artifacts were manufactured in the late eighteenth to early nineteenth century. The cellar was probably buried by the first quarter of the nineteenth century.

Both colonial structures on lots 267 and 268 retain significant archaeological integrity. A further investigation into the date of construction for the building on colonial lot 267, possible uses for this building, and how the building fit into the surrounding landscape will be presented in the next chapter.

Ravine

Figure 13. Plan view of ravine fill with intact ravine boundaries.

Figure 13. Plan view of ravine fill with intact ravine boundaries.

During the seventeenth century, a ravine cut through the excavation area in a roughly east to west direction (Figure 13). This ravine collected sand and debris as water flowed down to the west where it met the larger ravine presently beneath the Anthony Hay cabinetmaker's shop. This ravine contained banded deposits of sand, rubble, sandy-loam 17 and a few seventeenth-century artifacts. The south wall of the ravine sloped steeply, while the north wall was composed of a less dramatic slope. More sand and debris had collected along the south edge. The ravine was narrow and shallow to the east, measuring 1.20 meters wide and 0.26 meters deep. The west portion of the ravine within the excavation was wide and deep, measuring 6.20 meters wide and 0.70 meters deep. The structure on colonial lot 267 was constructed within this ravine, which promoted the filling and eventual sealing of the ravine in the early eighteenth century.

Middle Plantation Boundary Ditch

The earliest feature on the site was a boundary ditch that cut across the southeast corner of the excavation (Figure 14). This ditch was 0.64 meters wide and oriented along a southwest to northeast axis. It had been filled with a clean, olive brown silt loam with a band of lighter gray silt deposits along the bottom. The ditch sloped steeply along the south edge and gradually along the north edge. The complete lack of artifacts or inclusions suggested that this ditch predated most colonial activities on the site.

Figure 14. Plan view of Middle Plantation boundary ditch.

Figure 14. Plan view of Middle Plantation boundary ditch.

Partial excavation of this feature revealed four narrow depressions along the base and sides of the ditch at irregularly spaced intervals. These depressions measured approximately 10 centimeters across and 15 centimeters deep. The fill within these depressions was the same as that for the ditch. This suggested that these depressions were created while the ditch was in use. These depressions may have resulted from ditch maintenance such as dredging or cleaning activities.

The ditch was partially eroded in one area by the ravine, which provided evidence that the ditch predated the ravine as well as the structure that was constructed within the ravine. Thus, the ditch relates to early to mid seventeenth-century activities on the site. Similar 18 ditch features oriented off the Williamsburg town grid have been recovered at other sites in Williamsburg, such as the Peyton Randolph site, Shields Tavern, the Nicholson-Tyler site, and the Tucker House, for example. These features are often all that remains of the earliest historical occupation.

Chapter IV:

Discussion

This discussion provides a further investigation of the presently most perplexing features uncovered on the Ravenscroft site, the colonial structure and its associated trash midden. These finds require a closer investigation in order to assign a date to the structure, understand the activities that took place there, and locate the building within the surrounding community.

Historical documents have made no mention of the construction date for the structure on colonial lot 267. Christopher Jackson purchased the lot from the Trustees of Williamsburg in 1713/14, yet there is no mention of what buildings, if any, existed on the lot at that time, nor of what became of the lot after this time until 1731, when it was included in Thomas Ravenscroft's holdings. The low price that Jackson paid for the lot suggests that it was undeveloped at the time of purchase; however, a few years earlier several Middle Plantation brick structures had been fairly appraised at less than one pound each, indicating they had very little value to eighteenth-century inhabitants of Williamsburg (McIlwaine 1910:4:69). Archaeological evidence from the midden artifact assemblage excavated during the 1998 field season and the architectural features documented by James Knight in 1954 have provided information concerning a general period for construction, yet further research is needed to pinpoint the date of construction more precisely.

The midden assemblage lay directly above the builder's trench left from the construction of the building. The youngest artifacts in the midden included several sherds of pottery produced by the William Rogers pottery factory in Yorktown, Virginia, first producing in 1725. The clay cap sealed the midden soon after this date. But the question remains of how long the midden had been left open prior to the addition of the clay cap.

Bands of erosional deposits within the midden suggest that the deposit had been left open over some period of time. Additionally, the large quantity of artifacts in the assemblage manufactured in the mid- to late-seventeenth century, such as the onion and mallet shaped wine bottles, rectangular case bottles, locally-produced tobacco pipes and the presence of daub, indicate that the midden had been in use for some time before 1725. Several fragments of flat clay roofing tile, which very likely entered the trash deposit as elements of construction debris from the nearby building, suggest an extended period for the midden of several decades. Flat and rounded ceramic roofing tiles were an architectural component of several seventeenth-century brick buildings, such as the tiles from John Page's dwelling and kitchen, the Nassau Street Ordinary located beneath Nassau Street, Rich Neck Plantation, and numerous sites in Jamestown. However, there is very little evidence of the use of clay tiles as roofing materials in the eighteenth century.

Only one eighteenth-century site in Williamsburg, the Anthony Hay cabinetmaker's shop, has produced a large number of flat, clay roofing tiles (Noël Hume 1961). Interestingly, the Hay shop was located immediately downhill from the Ravenscroft site. It is possible that the clay tiles recovered from the Hay site did not come from the Hay roof but were introduced to the site from colonial lot 267. Physical evidence from tests performed on the 20 clay tiles supports this possibility. Preliminary data from xero-radiographic analysis, which produced a very detailed view of the internal composition of the tiles, and acid extraction tests, which provided a chemical analysis of certain elements within the ceramic body, have determined that flat roofing tiles from the John Page house and kitchen, the tiles from the Nassau Street Tavern, and the tiles recovered from the Hay site were all manufactured in John Page's kiln. Considering that the Hay cabinetmaker's shop was constructed between 1745 and 1756, decades after the Page kiln ceased to operate, it is thus possible that the tiles recovered from Hay had belonged to an older, nearby structure. In 1954, Knight recovered several flat, ceramic tiles from the cellar at the Ravenscroft site. This year, tiles were also recovered from the sealed midden context. A tiled roof on the Ravenscroft structure is highly suggestive of a pre-1700 date of construction, yet again it is possible that the roofing tiles were from another, earlier building. Further analysis of larger samples of roofing tile from the Ravenscroft, Hay and Page sites may shed light on the source of these tiles.

In 1954, Knight documented the southern half of the Ravenscroft structure with scaled drawings and photographs. Initially, Knight interpreted the structure as a single cell, built in the early eighteenth century (Noël Hume and Barrow 1962). But since that time, seventeenth- and eighteenth-century architecture in Tidewater Virginia has been the subject of several studies as more archaeological evidence has enlightened researchers on the building styles that have since disappeared from the landscape (Carson et al. 1981; Neiman 1978, 1996; Markell 1994; Miller 1994). The results of this research have provided a new outlook on the Ravenscroft site foundations.

In the early Middle Plantation period, most dwellings were small and of earthfast construction. This building method made use of widely available wooden materials as well as techniques that did not require heavy labor investments. A notable exception to this was Secretary Richard Kemp's dwelling, Rich Neck Plantation, which was possibly the most substantial building constructed by the 1640s outside of Jamestown. The dwelling at Rich Neck was 35 feet by 20 feet in size, with a hall and parlor plan, a central "H" chimney and a lobby entrance. It was constructed entirely of brick and probably rose one and a half stories high. The hearth was most likely all brick, but may have been wattle and daub. This type of house plan was used during the Medieval-period in England as well as throughout the colonies during the seventeenth century (McFaden 1994).

Like Secretary Kemp, John Page, a wealthy Middle Plantation landowner, erected architecturally progressive buildings for his time in the present-day Williamsburg area. Page likely contributed to the success of Middle Plantation with the construction of an immense and imposing brick dwelling and at least seven brick outbuildings. The buildings in Middle Plantation were stylistically impressive, with imposing and permanent plantations dotting the landscape. In addition to the more typical post structures, the remains of several brick buildings have been excavated in Williamsburg that dated to the Middle Plantation period. Such structures include John Page's house and settlement, his son Francis Page's dwelling, the Bruton Parish church, The College of William and Mary, the Jones cellar, the Nicholson cellar, two structures behind the Wythe House, and fragments of buildings belonging to the Bray Plantation.

21The Middle Plantation brick buildings have been characterized by the following: large foundations that supported one and a half stories; large plan dimensions for the period; ceramic roofing tiles; tiled floors; plastered walls; casement windows with diamond shaped glass panes; brick-lined cellars; fireplace tiles; architectural stone; and brick outbuildings. The structure on colonial lot 267 exhibited several of these features, such as a large, brick foundation measuring one and a half bricks wide under the southern half of the structure, ceramic roofing tiles, plastered walls, a brick-lined cellar, and dressed slate. In addition, several lead window casings and window glass fragments indicated diamond shaped panes. Some of these architectural details continued to be used in the eighteenth century.

Combining the artifactual evidence from the midden with the architectural style of the associated building, the construction period for the building could either have been during the late seventeenth-century Page ownership, before Williamsburg had been established, or during the early eighteenth-century Jackson ownership. Supporting a Middle Plantation construction period are the many late seventeenth-century artifacts, the tiled roof, the substantial brick-lined cellar combined with earthfast construction, the orientation of the narrow end with central cellar entrance towards Nicholson Street, and the likelihood that the entrance faced away from Nicholson Street.

On the other hand, the building may have been a product of early development efforts in Williamsburg. Supporting this scenario is the building's other possible entry style, the front side passage, which would have faced onto Nicholson Street and oriented the building only four degrees off the Williamsburg town grid. In addition, the low price that Jackson paid for the property in 1713/14 indicated that the property was undeveloped at that time.

Presently, the archaeological, architectural and documentary evidence support both the possibility that the building on colonial lot 267 was constructed during the seventeenth-century Page ownership and the possibility that the building was constructed after Jackson purchased the property from the Williamsburg Trustees in 1713/14. Additional archaeological work may clarify in which period the building was erected. The midden associated with this building had begun to be filled immediately after the building was constructed. This midden was left open until it was sealed with a clay cap around 1725. Artifacts recovered form the cellar fill in 1954 indicated that the building continued to stand until the mid- to late-eighteenth century.

In order to determine the types of activities that occurred in and around the structure, a comparison was made between the artifact assemblage from the midden and other nearby sites with similar dates of occupation in which the general use of the sites is known. Considerable variations occur between sites, yet general trends may help to eliminate certain uses for the Ravenscroft building.

The sites used in this comparison include CG-10, the Hornsby site, the Page kitchen and the Armistead tavern/coffeehouse. CG-10 is a late seventeenth-century domestic site located within the Greene Tract, east of Carter's Grove about seven miles southeast of Williamsburg. Structures and features on the site where excavated during a Phase I/II investigation in 1992 (Moody 1992). The Hornsby site is a middle to late seventeenth-century domestic site located off the Country Road between Colonial Williamsburg and 22

| Glass | Ceramics | Tobacco Pipes | Bone | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site/ Context | Total Artifacts | N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % |

| Ravenscroft | 8683 | 6134 | 70.6 | 810 | 9.3 | 197 | 2.3 | 1542 | 17.8 |

| CG10/ Domestic | 486 | 41 | 8.4 | 39 | 8.0 | 229 | 47.2 | 117 | 36.4 |

| Hornsby/ Domestic | 3250 | 779 | 24.0 | 302 | 9.3 | 108 | 5.2 | 2061 | 63.4 |

| Page/ Kitchen | 1129 | 72 | 6.4 | 53 | 4.7 | 56 | 5.0 | 948 | 84.0 |

| Armistead/Tavern | 67340 | 19102 | 28.4 | 10910 | 16.2 | 4306 | 6.4 | 33022 | 49.0 |

| Site/ Context | Glass | Ceramics | Tobacco Pipes | Bone |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ravenscroft | I | II | V | V |

| CG10/ Domestic | IV | IV | I | IV |

| Hornsby/ Domestic | III | III | III | II |

| Page/ Kitchen | V | V | IV | I |

| Armistead/ Tavern | II | I | II | III |

The artifacts from the Ravenscroft midden, CG-10, the Hornsby site, the Page kitchen and the Armistead midden were compared based on relative frequencies of glass, ceramics, tobacco pipes and faunal remains. These relative frequencies indicated which types of sites tended to have similar proportions of all artifact classes, and which sites had artifact assemblages dominated by a specific artifact category. The results of this comparison showed that CG-10 and Hornsby, both domestic sites, had a similar distribution of artifacts across categories. Thus similar disposal rates of glass, ceramics, tobacco pipes and bone occurred at both of these sites. The Armistead coffeehouse also exhibited similar artifact frequencies across all categories, showing a disposal rate for all four types of artifacts similar to the domestic sites, yet with a much higher number of artifacts. In contrast, the Page kitchen assemblage was heavily weighted towards faunal remains and comparatively lacked other types of artifacts. This indicates, as expected for a kitchen, that bone had been discarded at a faster rate than glass, ceramics or tobacco pipes.

23What does this indicate for the Ravenscroft assemblage? The relative frequencies of glass and ceramic items far outweighed the relative occurrence of tobacco pipes and faunal remains. This pattern stands apart from the even frequency distribution of the domestic and tavern/coffeehouse assemblage, and the high frequency of bone encountered at the kitchen. This indicates that the use for the Ravenscroft building during the late-seventeenth and early-eighteenth century was not primarily as a dwelling, kitchen or public house, though domestic activities could have been masked by other uses of the building. The activities that did occur of the site generated a high number of wine bottles; a bale seal and coin weight were also found in the assemblage. Thus, the site may have been used for a combination store and dwelling. This interpretation is tentative as the artifacts have all come from one large feature. Further excavation may reveal other activities that occurred near the late seventeenth or early eighteenth century structure on colonial lot 267.

Chapter V:

Research Summary and Recommendations

Research Summary

The 1998 archaeological field season revealed intact features from the eighteenth-century capital era in Williamsburg and its predecessor, the seventeenth-century Middle Plantation colonial settlement. The major features discovered, or in one case rediscovered, on this site include: a late seventeenth-century or early eighteenth-century structure tentatively identified as a combination store and dwelling; a large refuse deposit, sealed by a thick clay cap, containing numerous artifacts from the late Middle Plantation and early Williamsburg eras; a pair of structural posts from the eighteenth century, the purpose of which has yet to be determined; and a Middle Plantation era boundary ditch, perhaps from the earliest occupation of the excavation area in the historic period. No finds related to the pre-colonial period were recovered.

Recommendations

The excavation area spanned colonial lots 267 and 268, both of which contain colonial period foundations. A large, winged structure was located on lot 268 by Knight in 1954. This structure was outside the limits of the present excavation, yet brick foundations and other archaeological features remain intact on this lot. As one of the substantial and long-standing homes of Williamsburg, further excavation of this site would provide information on the lifestyles of high status individuals during the colonial and early national periods. In addition, the integrity of the remains would make accurate reconstruction of this building possible. Therefore, this lot is recommended for future archaeological research.

On colonial lot 267, the foundation of a unique structure from the late Middle Plantation or early Williamsburg periods has been partially excavated. Significant archaeological features associated with this building have also been found. Yet several questions concerning this structure remained unanswered or only tentatively answered. Further excavation may illuminate the date the structure was built, the architectural features of the building constructed in a stylistically transitional time period, and the activities that occurred on this lot. Similar to the foundations on the neighboring lot 268, these foundations retain significant integrity, making accurate reconstruction of this building a distinct possibility.

References Cited

- 1930

- Speeches of Students of the College of William and Mary Delivered May 1,1699. William and Mary Quarterly 10(2nd s.): 323-337.

- 1998

- Personal communication. Department of Archaeological Research, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1988

- Impermanent Architecture in the Southern Colonies. In Material Life in America: 1600-1860, edited by Robert Blair St. George, pp. 113-158. Northwestern University Press, Boston.

- 1998

- Personal communication. Department of Archaeological Research, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

- 1995

- "A Verie Fit Place To Erect A Great Citie": Comparative Contextual Analysis of Archaeological Jamestown. Ph.D. dissertation, Department of American Civilization, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia.

- 1954

- Archaeological Survey of Foundations- N.W. corner of Botetourt and Nicholson Streets (Ravencroft) Williamsburg, Virginia. Map on file at the Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Williamsburg.

- 1992

- Solid Statements: Architecture, Manufacturing and Social Change in Seventeenth-Century Virginia. In Historical Archaeology of the Chesapeake, edited by Paul A. Shackel and Barbara J. Little, pp. 51-64. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

- 1994

- "Richneck Plantation: An Example of Permanent Architecture in the 17th Century." Paper presented at the annaul meeting of the Council for Northeast Historical Archaeology, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1910

- Journals of the House of Burgesses. 13 vols. Virginia State Library, Richmond.

- 1998

- "Upon the Palisado" and Other Stories of Place from Bruton Heights. Colonial Williamsburg Research Publications, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg. 26

- 1992

- The Country's House Site: An Archaeological Study of a Seventeenth-Century Domestic Landscape. In Historical Archaeology of the Chesapeake, edited by Paul A. Shackel and Barbara J. Little, pp. 65-83. Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C.

- 1993

- Phase II Archaeological Investigation of the Locust Grove Tract Carter's Grove Plantation. Report on file, Department of Archaeological Research, The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation, Williamsburg.

- 1975

- American Slavery-American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia. W.W. Norton and Company, New York.

- 1994

- "The Aspirations, Ambiance and Actualities of Middle Plantation." Paper presented at the annual meeting of the Council for Northeast Historical Archaeology, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1984

- Domestic Architecture at the Clifts Plantation: The Social Context of Early Virginia Building. In Common Places: Readings in Vernacular Architecture, edited by Dell Upton and John Michael Vlach, pp. 292-314. University of Georgia Press, Athens, Georgia.

- 1993

- Temporal Patterning in House Plans from the 17th Century Chesapeake. In The Archaeology of 17th-Century Virginia, edited by Theodore R. Reinhart and Dennis J. Pogue, pp. 251-284. Archaeological Society of Virginia Special Publication No. 30. Dietz Press, Richmond.

- 1961

- Ravenscroft Site Archaeological Report, Block 28 Lot 267. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series No. 1557. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1962

- The Anthony Hay Site Block 28, Area D, Colonial lots 263 and 264, Report on Archaeological Excavations of 1959-1960. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series No. 1552. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1969

- A Guide to Artifacts of Colonial America. Alfred A. Knopf, New York.

- 1954

- Ravenscroft Site Historical Report, Block 28 Lot 266, 267, 268. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series No. 1556. Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library, Williamsburg, Virginia.

- 1998

- Personal communication. Architectural Research Department, Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.